89th Symphony (Haydn)

The Symphony No. 89 in F major was composed by Joseph Haydn in 1787.

Composition of the symphonies 88 and 89

Against the background of their genesis, the symphonies 88 and 89 can be understood as a contrasting pair of works. For general information on the two “sister symphonies”, see No. 88 .

In contrast to Symphony No. 88, No. 89 is performed less often and is sometimes considered less popular. Haydn probably composed the work under time pressure (possibly the departure of Johann Tost, see No. 88), since he was based on two movements from the “Lyre Concerto” Hob. VIIh No. 5, which he composed in 1786 for King Ferdinand of Naples, Recourse: The andante was adopted largely unchanged and orchestrated for orchestra, the Vivace assai contains an additional minor part in the symphony version. The work is judged differently in literature:

“Symphony No. 89 (...) has always been somewhat overshadowed by its incomparably more popular sister in G major No. 88; next to this - according to HC Robbins Landon - she looks like a dull companion. Reserved, cool and of a flawless form concept, they remind you of the perfectly shaped porcelain figurines of that time. When it is said that JOSEPH HAYDN opened the doors of the eighteenth-century drawing room to let in fresh air, he temporarily closed them again for number 89. This impression is mainly caused by those musical passages that Haydn reused from other pieces of music. (...) The first movement does not need to put its light under the bushel. "

“The other (…) Symphony No. 89 in F major (…) stands somewhat in the shadow of her sister. All in all, it seems to be more of a casual work, as Haydn used 2 movements from his Concerto for 2 Lyres, Horns and Strings (1785) again (...). The first movement (Vivace) is a perfectly balanced sonata movement, with a rather abstract 1st and a personal chatting 2nd theme. "

“While Symphony No. 88 in G major achieved great fame as one of the most beautiful and excellently worked works by Haydn, Symphony No. 89 never really caught on. The reason for this may be to be found in a quality that is not quite as convincing. The minuet, for example, doesn't seem very inspired and strangely dry. Even the final rondo does not show the wealth of colors and surprises that we are used to from Haydn. (...) The masterpiece of the symphony is unquestionably the first movement. Even if he hardly has the vital power of Symphony No. 88, he is characterized by an exceptionally relaxed liveliness and sovereign design. "

“(…) The minuet is only muted popular and of great elegance, and the finale is a rondo; the two key clauses are extremely different in terms of their subject matter and character. (...) [The Trio of the Minuet] is a more elegant than popular Länders who in the middle section carries out the head motif and the final motif of the subject one after the other - a striking emphasis that points back to the main part of the minuet, which is made up of two contrasting motifs. "

“In the first movement of the Symphony F No. 89 from 1787 (...) the development and recapitulation swap roles in a delightful way. (...) This shift in function in no way affects the overarching symmetry of this movement, but rather reinforces it, since through the regrouping Haydn is now able to create a mirror symmetry in which the opening theme appears completely after the second theme, namely in an enchanting new orchestration for violas and bassoons with accompanying horns, flutes and strings. No work could better show the abyss between academic ex post facto regulations for the sonata form and the living rules of proportion, balance and dynamics that actually determine Haydn's art. "

To the music

Instrumentation: flute , two oboes , two bassoons , two horns , two violins , viola , cello , double bass . There are different opinions about the involvement of a harpsichord or fortepianos as a continuo instrument in Haydn's symphonies.

Performance time: approx. 20 to 25 minutes.

When it comes to the sonata form used here, it should be noted that this model was only designed at the beginning of the 19th century (see there). - The description and structure of the sentences given here is to be understood as a suggestion. Depending on the point of view, other delimitations and interpretations are also possible.

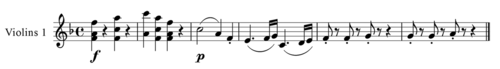

First movement: Vivace

F major, 4/4 time, 172 bars

Haydn opens the symphony with an introductory “curtain” of five forte chords in F major. The following first theme with a calm, singing character is played piano by the strings. It shows a periodic structure with a front and a trailer of four bars each. Then the entire thematic unit consisting of “curtain” and melodic theme is repeated, now with bassoon and descending counterpart of the flute and a short piano echo. From bar 19, a tutti block begins as a transition in the forte, in which the violins play energetic, falling sixteenths, offset by bars. Bars 28–30 are dominated by chromatic syncopations , which merge into a dialogical knocking and with their final turn announce the second theme. This (from bar 43, in the dominant C major) is four bars and has a memorable, song-like melody. First performed by the 1st violin on an eighth "carpet" of the 2nd violin and viola, the 1st oboe repeats the melody with an opposing voice in the flute (derived from the theme). The final group (bar 52 ff.) In the forte is again characterized by energetic sixteenth-note figures on the violins, whereby at the beginning a motif with two-tone repetition is noticeable (final group motif). The exposure is repeated.

The development (from bar 59) initially takes up the energetic sixteenth-note movement of the final group, now turned towards the minor. Structurally, the rest of the course largely corresponds to that of the exposition: from bar 63, the strings start from E flat major with the first theme. The head motif of the theme (descending triad) then wanders through the woodwinds, before the transition section with the dialogue of the violins in F minor follows from bar 77. This section is somewhat expanded compared to the exposure and is marked by a chromatically falling line in the bass. The syncope section is left out, followed by a knocking motif (from measure 88) and the second theme (from measure 93), which is turned to A minor (dominant parallel). The final group surprisingly comes to a standstill after the final group motif with a total of three general breaks. In the mysterious piano, first the strings, then the winds, lead their heads from the first theme to the recapitulation.

The recapitulation (bar 111 ff.) Begins as at the beginning of the sentence with the chord strike “curtain”. The other first theme is (heavily) modified to the extent that the flute and bassoon take up the material in a dialogue over an eighth carpet of violins. The transition passage with the dialogue of the violins (bars 122 ff.) Begins in D flat major. This is followed by the section with the knocking motif (bar 127 ff.) And the second theme (bar 139 ff), played first by the 1st oboe, then by the bassoon with a short opposing voice in the flute. The end of the movement is extended as a coda : Instead of the familiar closing group, the first theme has another appearance in bassoon and viola (bars 152 ff.), Followed by the syncopation passage extended to five bars, the dialogue motif of the violins from the transition and the concluding chord melody . The development and recapitulation are also repeated.

Second movement: Andante con moto

C major, 6/8 time, 76 bars

The movement represents an (extensive) re-instrumentation of the slow movement from the fifth of the concertos for two radlers (F major, Hob. VIIh: 5), which Haydn had composed for King Ferdinand of Naples in 1786 (see above). The sentence has a superordinate three-part form AB-Á:

- A part bars 1–29: This part is also structured according to the three-part ABÁ scheme. A part (bars 1–12): The catchy, vocal main melody is first introduced by the strings and the flute. It has a pastoral siziliano character ("shepherd's idyll", dotted rhythm). The melody is then repeated again with the other wind instruments (oboes, bassoon, horns) instead of the flute, the strings now play pizzicato . The B part continues the theme from the dominant G major with a short forte insert and returns in bar 24 to the main melody (theme) in C major (A 'part). A and B with A 'are repeated.

- B-part bars 30–47: The section contrasts with the previous event through the use of the tutti in fortissimo and the abrupt F minor. It begins as a cadenza- like sequence of "dramatic" chord strokes (CFGC), which is underlaid with flowing sixteenth notes. The flowing movement is then continued piano with Forte accents . The first section, which is repeated, ends in E flat major. The second (not repeated) section begins with chord strokes in C major, after which a short polyphonic passage in F minor begins (bar 39 ff.) - again accompanied by the flowing sixteenth notes.

- Á part bar 48–76: This section is a variant of the A section. The subsections are not repeated. Haydn underlined the last appearance of the theme with the sixteenth movement (pizzicato). The sentence breathes pianissimo after a final turn.

Third movement: Menuet. Allegretto

F major, 3/4 time, with trio 68 bars

The upbeat minuet begins forte with a four-bar motif of the solo oboes, bassoons and horns. The tutti responds in a four-bar motif, followed by another, contrasting four-bar with a flowing piano eighth note for the solo flute. The second part picks up on the head of the opening motif in the violins and oboes, and then underlays it with a continuous staccato eighth note movement, similar to voices. The main part is taken up again in bar 25. The piano ending with the eighth movement of the flute from the first part now appears forte, underlaid with organ point , emphasized again in the last two bars by energetic hammering fortissimo beats.

The trio is also in F major. In the first part, the first violin and flute play a quiet, rural melody with strings. At the beginning of the second part, the bass leads the theme head as a variant, while the upper parts (flute, 1st oboe and 1st violin) play a short counterpart. Then the flute and 1st oboe repeated the final turn of the first part before the main theme starts again from bar 61.

Fourth movement: Finale. Vivace assai

F major, 2/4 time, 211 bars

The movement is structured as a rondo (form: ABAC-Á) and, apart from the F minor section composed for this symphony, is based on the final movement of the fifth concerto for two vaults (F major, Hob.VIIh: 5), the Haydn Composed in 1786 for King Ferdinand of Naples (see above).

- The melody of the refrain (bars 1–24) has a cheerful folk character. It is upbeat and is performed by the flute, 1st oboe and 1st violin. Typical (also for the rest of the movement) is the double upbeat tone repetition. The refrain is again divided into three parts (AB-Á). When picking up the main melody, Haydn stipulated “ strascinando ” for the flute and the 1st violin , ie the falling fifth from the long held C to the upbeat F of the main melody should be played with intermediate notes. In this way, the prelude is pointedly "coarse" highlighted.

- First couplet (B flat major, bars 25–56): Like the refrain, this part is also divided into three parts. Typical are the prelude (as in the chorus), a sixteenth-note figure and the change between winds and tutti. The final turn (bars 55–56) is identical to that of the refrain. Bars 57 to 68 lead - surprisingly starting from G minor - back to the refrain (F major) with the opening motif and the sixteenth-note figure.

- The refrain (bars 69–91) begins after a general pause, the sections run through without repetition.

- The second couplet (bars 92–136) contrasts strongly with the previous occurrence of the movement (as well as with the rest of the, more light-hearted sound of the symphony) with F minor, numerous syncopations, polyphony and the overall wild character. The sixteenth-note pendulum figure of the 1st violin is characteristic of the less melodious section. This part is also made up of three parts, the second part starts from A flat major. With the upbeat knock - separated by a general pause - the refrain is announced again.

- The refrain (bars 137–160) then runs through again without repetitions.

- The coda (from bar 161) initially expands the end of the chorus, but ends up on a fallacy sustained by fermata (bars 168/169). Then the strings and winds throw the opening motif to each other like a dialogue with dynamic contrasts (piano, pianissimo, fortissimo) and then expand it over sixteenths to a tremolo . The tremolo turns into rapid sixteenth runs in the bass. Haydn ends the movement with a motif (piano) derived from the main melody, which is repeated an octave lower, and forte chord strikes on F.

Individual references, comments

- ↑ a b Information text on the 89th symphony in the project “100 & 7” of the Haydn Festival Eisenstadt. http://www.haydn107.com/index.php?id=2&sym=89 , accessed May 19, 2011.

- ↑ In the book The Symphonies of Joseph Haydn. Universal Edition & Rocklife, London 1955, Howard Chandler Robbins Landon writes on page 404: “This F major symphony, which returns to the superficialities of the previous period, appears, in its cold, glassy perfection, like a parody of Haydn made by a malicious and brilliant ill-wisher; all the composer's clever ways, all his neat pauses and witty instrumentation, seem to have been cleverly mimicked. "

- ^ Alfred Beaujean: Symphonies Hob. I: 88-92. In: Harenberg concert guide. 3. Edition. Harenberg Kommunikation Verlags- und Mediengesellschaft, Dortmund 1998, ISBN 3-611-00535-5 .

- ^ Klaus Schweizer, Arnold Werner-Jensen: Reclams concert guide orchestral music. 16th edition. Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart, ISBN 3-15-010434-3 , p. 148.

- ↑ Dieter Rexroth : Symphony No. 89 in F major (Hob. I: 89). In: Wulf Konold (Ed.): Lexicon Orchestermusik Klassik A - K. B. Schott's Sons, Mainz 1992, ISBN 3-7957-8224-4 , pp. 172–174.

- ↑ Ludwig Finscher: Joseph Haydn and his time. Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2000, ISBN 3-921518-94-6 , p. 348.

- ↑ Charles Rosen: The Classic Style. Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven. Bärenreiter-Verlag, 5th edition, Kassel 2006, ISBN 3-7618-1235-3 , pp. 174-175.

- ↑ Examples: a) James Webster: On the Absence of Keyboard Continuo in Haydn's Symphonies. In: Early Music Volume 18 No. 4, 1990, pp. 599-608); b) Hartmut Haenchen : Haydn, Joseph: Haydn's orchestra and the harpsichord question in the early symphonies. Booklet text for the recordings of the early Haydn symphonies. , online (accessed June 26, 2019), to: H. Haenchen: Early Haydn Symphonies , Berlin Classics, 1988–1990, cassette with 18 symphonies; c) Jamie James: He'd Rather Fight Than Use Keyboard In His Haydn Series . In: New York Times , October 2, 1994 (accessed June 25, 2019; showing various positions by Roy Goodman , Christopher Hogwood , HC Robbins Landon and James Webster). Most orchestras with modern instruments currently (as of 2019) do not use a harpsichord continuo. Recordings with harpsichord continuo exist. a. by: Trevor Pinnock ( Sturm und Drang symphonies , archive, 1989/90); Nikolaus Harnoncourt (No. 6-8, Das Alte Werk, 1990); Sigiswald Kuijken (including Paris and London symphonies ; Virgin, 1988-1995); Roy Goodman (e.g. Nos. 1-25, 70-78; Hyperion, 2002).

Web links, notes

- Recordings and information on Haydn's 89th Symphony from the "Haydn 100 & 7" project of the Eisenstadt Haydn Festival

- Symphony No. 89 by Joseph Haydn : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Thread on Symphony No. 89

- Joseph Haydn: Sinfonia No. 89 F major Hob. I / 89. Philharmonia No. 789, Universal Edition, Vienna 1964. Series: Howard Chandler Robbins Landon (Ed.): Critical edition of all symphonies. (Pocket score), pp. 59–106.

- Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 89 F major. Ernst Eulenburg, No. 558 (pocket score, without year)

- Andreas Friesenhagen: Symphonies 1787 - 1789. In: Joseph Haydn Institute Cologne (Hrsg.): Joseph Haydn works. Series I, Volume 14. G. Henle-Verlag, Munich 2010, 272 pages