88th Symphony (Haydn)

The Symphony no. 88 in G major composed Joseph Haydn to 1787.

Composition of the symphonies 88 and 89

After the great success of the "Paris Symphony" (see Symphony No. 82 ), Joseph Haydn composed the five symphonies No. 88 to 92 in Vienna and Esterháza in the years 1787 to 1789. Here, too, there was a reference to Paris, whereby the genesis is complicated because of the printing rights (see below). Nos. 88 and 92 are among Haydn's most frequently played symphonies, while Nos. 89, 90 and 91 appear rarely in the repertoire and as a recording.

In 1788 Johann Peter Tost, who was a violinist in the Esterhazy orchestra from 1783 to 1789, traveled to Paris. Haydn gave him six new string quartets (Opus 54 and 55) and two new symphonies (Nos. 88 and 89), which Tost was likely to sell to the publisher Siebert. However, as early as November 1788, Haydn had heard that the Viennese publisher Artaria also intended to publish the works. This disturbed Haydn because he had to assume that Tost had also sold the works to Artaria: “I heard these days that your wellbeing was to have bought my very last 6 new quartets, including 2 new symphonies, from Mr. Tost himself Since I would like to know for various reasons whether it is or not, I kindly ask you to let me know about it by the first day of the post ”(letter of September 22, 1788 to Artaria).

Presumably Haydn wanted to compose two further symphonies for Siebert in addition to nos. 88 and 89 (letter to Joseph Eybler of March 22, 1789: “... that two of the symphonies I composed for H. Tost will soon appear in print. The other two, however, will only come to light in about a few years. ”).

Then on April 5, 1789, Haydn wrote to Siebert, referring to the possible publication by Artaria: “Monsieur, I am very surprised that I have not yet received a letter from you, as Mr. Tost wrote to me a long time ago, you I would have bought 4 symphonies and 6 piano sonatas for a hundred Louis d´or: I am sorry on my part, in that I owe H. Tost the 4 symphonies on this arth, that he would have me on these 4 pieces 300 f. has to pay. do you want this payment their 300 f. also take yourself, so I combine these four symphonies for you to compose, of which six are piano sonatas, but Mr. Tost has no pretension from me. So he cheated on you and you can use this to seek your rights in Vienna. Now I ask you sincerely to write to me how and how Mr. Tost performed in Paris, whether he had no Amour there, and whether he also sold the six quartets, and how dearly, to you. item whether the quartets and the 2 symphonies will soon appear in Stich, I ask you to report everything to me immediately. "

On July 1, 1789, Artaria actually announced the same works in Vienna (nos. 88 and 89). Haydn then wrote to Artaria on July 5, 1789: “Now I would like to know one truth, namely from whom you received the 2 new symphonies, as you recently announced, whether you bought such directs from Mr. Tost or already stabbed by Mr. Sieber from Paris. If you have bought the same from Mr Tost, I urge you to have a separate written assurance given to me about it, because, as I hear, Mr Tost pretends that I have sold these 2 symphonies to you and that I am getting one inflicted great damage. "

In the meantime, the Bastille had been stormed in Paris on July 14, 1789 . After Sieber had probably accepted Haydn's demand for salary (letter of April 5, 1789), Haydn wrote on August 28, 1789 that he wanted to compose the four symphonies and that one of them should be called the “National Symphony” (ie for France). Apart from nos. 88 and 89 (composed as early as 1787), Haydn apparently never composed these. In July 1789, nos. 89 and 88 (in that order) continue to be published by Longman & Broderip in London, and in 1790 in Berlin, Amsterdam and Offenbach.

After this incident, Haydn took precautionary measures to prevent the “theft” of his symphonies: A student made a fair copy of the work, which was then distributed in individual parts to various copyists so that they could not make a copy of the entire work. However, this measure did not work. With the printing rights to the symphonies nos. 88 and 89, Haydn had apparently "got the short straw" on business.

Against the background of their genesis, the symphonies 88 and 89 can be understood as a (contrasting) pair of works. What is remarkable about the symphony No. 88 (and often highlighted in the literature) is the “lightness” of movements 1 and 4 in connection with catchy melodies on the one hand and strong thematic work on the other; also the Largo (in which Haydn uses trumpets and timpani for the first time in a slow movement) with its special timbre, which Johannes Brahms is said to have particularly valued: After Donald Francis Tovey , Brahms told John Farmer that he would like his ninth symphony to be like this sentence sounds. Tovey praises Symphony No. 88 for the fact that Haydn's quality of ingenuity and its economy are nowhere more remarkable than in this work.

To the music

Instrumentation: flute , two oboes , two bassoons , two horns , two trumpets , timpani , two violins , viola , cello , double bass . On the participation of a harpsichord - continuos are competing views in Haydn's symphonies. Timpani and trumpets are used from the second movement.

Performance time: approx. 25 minutes (depending on compliance with the prescribed repetitions in the 1st movement)

When it comes to the sonata form used here, it should be noted that this model was only designed at the beginning of the 19th century (see there). - The description and structure of the sentences given here is to be understood as a suggestion. Depending on the point of view, other delimitations and interpretations are also possible.

First movement: Adagio - Allegro

Adagio : G major, 3/4 time, bars 1-16

Haydn opens the symphony as a series of simple, separate chords in staccato , which are interrupted by pauses, have a solemn and solemn effect and are reminiscent of a sarabande . The first unit, determined by alternating forte and piano, comes to an end in bar 8 after a final turn with a dotted rhythm. In measure 4, a quick sixteenth-note phrase appears in the violin (in a similar form in the following Allegro). The new beginning in bar 9 leads to the dominant D major, in which the introduction ends with the sixteenth-note phrase.

Allegro : G major, 2/4 time, bars 17–266

The two violins begin piano with the dance theme, which is characterized by its prelude and triple tone repetition. Viola and bass begin in the aftermath. The eight-bar theme is then repeated in tutti and forte, with a sixteenth-note motif in the bass (possibly interpreted as derived from the corresponding figure in the introduction). The whole further sentence is based on the material of this topic (main topic, "monothematic" sentence structure). This can already be seen in the transition (bars 32–61, consistently forte), which puts several small motifs one after the other: for example from bar 36 with a variant of the sixteenth-note motif in unison . From bar 46 the head of the topic moves through the instruments with emphasis on the first bar: initially in unison, then sequenced in the bass and finally in the upper parts, here also offset between flute, 1st oboe and 1st violin as well as 2nd oboe and 2nd Violin.

The somewhat quieter “second theme” (from bar 61) in the dominant D major with its knocking prelude is derived from the material of the opening theme. A characteristic accompanying figure is a chromatic downward movement in oboe and bassoon. The four-bar theme is repeated with a flute and then changes to a forte ending, in which the sixteenth-note motif in the upper parts is underlaid by the unscrewing theme in the bass.

The final group (bars 77 ff.) Initially takes up the chromatic downward movement with the head from the main theme in the oboes (piano). The answer in the violins leads to a forte passage with the sixteenth-note motif and the tone repetition derived from the main theme (bar 85 ff., But now on the first and no longer on the second bar). The first section of the sentence (exposure) is repeated.

The development begins as a string passage in piano / pianissimo (bars 101–128). At first only the violins play the sixteenth-note motif and lead them into the harmoniously distant A flat major. With the use of the bass, the head of the main theme also appears. In tutti use from bar 129 (forte) the head of the main theme and the sixteenth-note motif are led through the instruments. Sometimes from bar 151 the head of the topic appears shifted to itself ( narrowing ). After an organ point on b, the tone repetition motif from the final group (tone repetition on the first measure) leads to the recapitulation, which begins after a short caesura in measure 179.

The recapitulation has been changed compared to the exposition: the flute accompanies the theme entry in the strings at the beginning, and the tutti entry of the theme in the forte (from bar 188) takes place in a different instrumentation (theme in the winds, counterpart in the violins, no bass). The transition is shortened and again varied, as is the second theme (from bar 227), whose thematic four-bar unit only sounds once and is then immediately continued. As in the exposition, the final group (bars from 240) begins with wind instruments (now flute and 1st oboe), but the tone repetition motif from the final group of the exposition is omitted. The movement closes with a final appearance of the main theme in the tutti. The second part of the sentence (development and recapitulation) is also repeated.

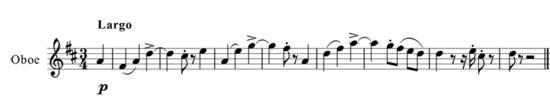

Second movement: Largo

D major, 3/4 time, 114 bars

The Largo is a set of variations, the changes affecting only the instrumentation and timbre in the accompanying voices, while the theme (mostly in parallel oboe and cello) remains unchanged. The surprising use of trumpets and timpani from a fortissimo outburst in the third section is remarkable. - The Largo is the first slow movement of a symphony in which Haydn uses timpani and trumpets.

- Section 1, presentation of the main theme (bars 1–12): Solo oboe and solo cello perform the vocal, periodically structured melody, accompanied by bassoon, horn and bass. The theme ends with a somewhat melancholy final turn in the strings (bars 8–12).

- Section 2 (bars 12–28): Voice leading in solo oboe and solo cello, pizzicato accompaniment of the violins, final turn chromatically extended as a transition to the next section.

- Section 3 (bars 28–52): Voice leading in solo oboe and solo cello, with short phrases in 1st violin; Final turn extended: outbreak in fortissimo with the first use of trumpets and timpani, “echo” of the outbreak piano in even quarters in flute & oboe as well as strings.

- Section 4 (bars 52–64): Voice leading in solo oboe, solo cello and flute, chromatic extension of the final turn as in section 2.

- Section 5 (bars 64–83): Voice leading in solo oboe and solo cello, with figurative runs in 1st violin. Final turn extended with an outbreak to D minor.

- Section 6 (bars 83–94): Voice guidance in 1st violin and solo cello, beginning in F major (previous thematic entries all in D major) with a change to D minor and A major, final turn shortened to three short forts -Outbreaks.

- Section 7 (bar 94 to the end): Voice leading in solo oboe, 1st violin and solo cello, continuous accompanying movement in 2nd violin, final turn extended similar to section 3.

Third movement: Menuetto. Allegretto

G major, 3/4 time, with trio 70 bars

The main melody of the powerful minuet is characterized by suggestions and two to three tone repetitions. In the short, echo-like aftermath (piano), the timpani and horns appear with a knocking accompaniment. The second part of the minuet initially leads into the B keys and then takes up the main theme in G major again from bar 33.

The trio is also in G major and contrasts with the minuet. The upper voices play a rustic, circling to monotonous dance on the piano, the timbre of which is also somewhat bizarre due to the "drone bass": bassoons and viola play sustained fifths , the bassoons are also headed "forte assai" (other instruments: piano). The fifths in bassoons and viola are lowered in parallel at one point in the two trio sections. Such “fifth parallels” are usually avoided.

Fourth movement: Finale. Allegro con spirito

G major, 2/4 time, 221 bars

- Bars 1–32: The movement begins with a memorable, entertaining and cheerful theme, which - as in the first movement - is characterized by tone repetition, staccato and upbeat. The periodic theme (eight bars from two times four bars) with regular eighth notes and a sixteenth phrase is initially only introduced by the strings and bassoon. The beginning of the sentence is reminiscent of a rondo main theme (structure AB-Á): the melody or the theme (bars 1–8) is repeated, followed by a middle section with a change of key, the full orchestra playing in forte and unison and taking up the main theme again , now also with part-leading flute. The middle section and revisiting the theme are also repeated (bars 9–32).

- Bars 32–52: In bar 32, the whole orchestra starts in the forte with rapid runs in the violins (G major).

- Bar 53–65: Variant of the first part of the theme in piano with the leading oboe and violin, bassoon and other strings. Beginning in the dominant D major, then briefly obscured minor and chromatic.

- Measure 66–84: The whole orchestra is used in the forte with virtuoso runs in the violins (D major), at the end a stressed prelude.

- Bars 85–108: Topic as at the beginning of the sentence, voice leading in flute and 1st violin, G major, without taking up the topic again (ie structure AB).

- Bars 109–158: passage composed of several voices with the elements of the theme (in bassoon and strings), mostly fortissimo, partly wild character, bars 136–138 short organ point on b, from bar 142 the upbeat tone repetition in individual groups of instruments is lost with somewhat eerie effect.

- Measure 159–190: theme in full form (AB-Á), G major.

- Bar 190 to the end: announced by solemn chord strikes (which briefly interrupt the previous perpetual motion machine character and are somewhat reminiscent of the introduction), a passage begins again with virtuoso runs in the violins (corresponding to section 4, but now in G major ). At the end, the theme appears again in the whole orchestra, now for the first time in the Forte.

“The finale is a perpetual motion machine 'sweeping away' (...). It is one of those sentences that still ring in the listener's ears as a 'catchy tune' hours after the end. ”Haydn uses such a“ perpetuum mobile character ”for example. B. also in the fourth movement of Symphony No. 96 .

Individual references, comments

- ^ Tost ran a flourishing illegal copier business in Esterháza (Walter 2007).

- ↑ Quotations of the letters in the following from Anthony van Hoboken: Joseph Haydn. Thematic-bibliographical catalog raisonné, Volume I. Schott-Verlag, Mainz 1957, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ 300 guilders

- ^ Michael Walter: Haydn's symphonies. A musical factory guide. CH Beck-Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-44813-3

- ↑ Ludwig Finscher: Joseph Haydn and his time. Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2000, ISBN 3-921518-94-6 , S- 346

- ↑ Donald Francis Tovey: Symphony in G Major “Letter V” (Chronological List, No. 88). - Essays in Musical Analysis. Symphonies and other Orchestral Works. London, 1935-1939, pp. 339-342.

- ↑ "I was told by John Farmer that he once heard Brahms play it with wallowing enthusiasm, exclaiming, I want my ninth symphony to be like this!" (P. 341)

- ↑ "The quality of Haynd's inventiveness is nowhere higher and its economy more remarkable than in this work." (P 339)

- ↑ Examples: a) James Webster: On the Absence of Keyboard Continuo in Haydn's Symphonies. In: Early Music Volume 18 No. 4, 1990, pp. 599-608); b) Hartmut Haenchen : Haydn, Joseph: Haydn's orchestra and the harpsichord question in the early symphonies. Booklet text for the recordings of the early Haydn symphonies. , online (accessed June 26, 2019), to: H. Haenchen: Early Haydn Symphonies , Berlin Classics, 1988–1990, cassette with 18 symphonies; c) Jamie James: He'd Rather Fight Than Use Keyboard In His Haydn Series . In: New York Times , October 2, 1994 (accessed June 25, 2019; showing various positions by Roy Goodman , Christopher Hogwood , HC Robbins Landon and James Webster). Most orchestras with modern instruments currently (as of 2019) do not use a harpsichord continuo. Recordings with harpsichord continuo exist. a. by: Trevor Pinnock ( Sturm und Drang symphonies , archive, 1989/90); Nikolaus Harnoncourt (No. 6-8, Das Alte Werk, 1990); Sigiswald Kuijken (including Paris and London symphonies ; Virgin, 1988-1995); Roy Goodman (e.g. Nos. 1-25, 70-78; Hyperion, 2002).

- ↑ Before z. B. Already in Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's Symphony KV 425 from 1783.

- ↑ by Kurt Pahlen ( Symphony of the World. Schweizer Verlagshaus AG, Zurich 1978 (foreword from 1966), p. 162) because of its symmetry as a "prime example of a 'classical' melody"

- ↑ In the Philharmonia score (see under sheet music) the “violoncello obligato” is listed separately (next to the line for parallel cello and double bass) and - like the 1st oboe - is entitled “Solo”.

- ↑ Information text (“Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 88 in G major, Hob.I: 88”) on Joseph Haydn's Symphony No. 88 of the Haydn Festival in Eisenstadt, http://www.haydn107.com/index.php?id = 2 & sym = 88 , as of February 2011.

Web links, notes

- Recordings and information on Haydn's 88th Symphony from the project "Haydn 100 & 7" at the Haydn Festival in Eisenstadt

- Thread on the symphony No. 88 with discussion of various recordings

- Wolfgang Marggraf: The Symphonies of Joseph Haydn. - Symphony 88, G major. Accessed May 5, 2011 (status of the text: 2009)

- Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 88 G major. Edition Eulenburg No. 487. Ernst Eulenburg Ltd., London / Zurich (pocket score)

- Joseph Haydn: Sinfonia No. 88 G major Hob. I / 88. Philharmonia No. 788, Universal Edition, Vienna 1964. Series: Howard Chandler Robbins Landon (Ed.): Critical edition of all symphonies (pocket score), 55 pp.

- Symphony No. 88 by Joseph Haydn : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Andreas Friesenhagen: Symphonies 1787 - 1789. In: Joseph Haydn Institute Cologne (Hrsg.): Joseph Haydn works. Series I, Volume 14. G. Henle-Verlag, Munich 2010, 272 pages