Johann Bessler

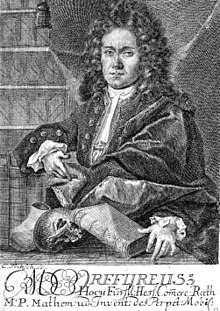

Johann Ernst Elias Bessler (* 1681 in Zittau (baptized on May 6th; † November 30th, 1745 in Fürstenberg ) was a German inventor of numerous machines, which he presented and demonstrated as Perpetua Mobilia . He also worked as a doctor (then called: “Quack”) and watchmaker. According to historical documents, his last name was actually "Beßler". His stage name Orffyre ( Latinized Orffyreus ) results from a ROT13 encoding of the surname.

Life

Before his first public appearance on June 6, 1712, Bessler was a traveler and adventurer who had learned manual skills in numerous countries and regions of Europe. It was in an Italian monastery that he first had the idea of building a perpetual motion machine. In Prague he made his first attempts, together with a rabbi and a Jesuit.

On June 6, 1712, Bessler presented a wheel in Gera that would not stop turning as soon as it was set in motion. It spun at 50 revolutions per minute. According to Bessler's Apologia, the wheel had a diameter of 3 ½ a shoe, which corresponds to approx. 105 cm, and a thickness of approx. 9.4 cm. The residents of Gera initially showed little interest in the "Bessler bike" - they may have been confused and deterred by Bessler's idiosyncratic character. For example, Bessler remarked that he had found the secret of eternal movement and that if his bike didn't work, his head could be cut off and put on public display.

The initial disinterest changed, however, after an official " certificate " for the Bessler wheel was given for the first time on October 9, 1712 . As with all certificates given for the Bessler bike, the drive mechanism was not described in detail. It was only confirmed that no energy could be added from the outside and that the wheel was still turning incessantly. Bessler offered his invention for 100,000 thalers , which was a very high sum for the time.

In 1713, Bessler moved to Draschwitz near Leipzig, where he built an even bigger bike (after the old one was destroyed) that could also do work. In the meantime the attention had become very high, so that three opponents of Bessler (Gärtner, Borlach and Wagner) distributed leaflets in which it was claimed that Bessler's bike was a fake. Thereupon Bessler destroyed his bike.

He later built a new bike in Merseburg . Because the attention was now even greater, Duke Moritz Wilhelm ordered a new inspection for October 31, 1715. Again a certificate was issued, but it was structured according to the same pattern as the first. The special thing about the Merseburg bike was that, although it was a little slower than its predecessor and had to be driven to take off, it could move in both directions. This was not possible with the first bike.

Bessler aroused the interest of Landgrave Karl von Hessen-Kassel (1670–1730) , who was interested in natural science . This offered Bessler to take him into his castle and to pay for all of Bessler's living expenses. In return, the landgrave was allowed to learn the secret of the wheel, although he was not allowed to reveal it to anyone.

On November 2, 1717, a rotating Bessler wheel was locked in a room in the Weißenstein Castle near Kassel (later Wilhelmshöhe Castle ) at the instigation of Landgrave Karl. The room where the rotating wheel was located was sealed so that no one could enter. When the seal was broken on January 4, 1718 and the room was re-entered after 54 days, the wheel was still rotating. Nobody had access to the room in the meantime. This experiment was based on a bet between Gärtner and Bessler for 10,000 Thaler, the content of which was the wheel: Gärtner demanded a four-week long-term test, during which it had to be absolutely ensured that the wheel was not exposed to any external energy. After the lost bet, gardener Bessler had to pay the bet amount.

In the course of the following years the Bessler bike was inspected again and again. Many well-known people of their time examined it, but always from the outside, and always only checked whether an energy was somehow hidden from the outside - which never seemed to be the case. Best known are Leibniz and 's Gravesande, who both inspected the wheel on October 31, 1715.

However, when the then very renowned Dutch mathematics and physics professor Willem Jacob 's Gravesande wanted to examine the axle where the drive system was hidden, Bessler, who had had serious psychological problems throughout his life, destroyed his bike in a fit of rage.

Since Bessler's bike became famous, two interested parties wanted to buy it at the asking price. First the Russian Tsar Peter the Great , who died in 1725 before he could see the wheel, which was a condition for him to buy it. The other interested party was the Royal Society of London . This purchase failed on Bessler himself, as he did not agree with the sales mode that the money should first be handed over to the Landgrave and only after an explanation of the drive mechanism by 's Gravesande to him.

Bessler and his bike were forgotten until a former maid of Bessler, Anne Rosine Mauersberger, informed the authorities on November 28, 1727 that the Bessler bike was a fraud. However, these allegations were dismissed by the court as Mauersberger got caught up in contradictions. 's Gravesande was on Bessler's side: he stated that the inventor had some psychological problems, but that the wheel worked independently of that.

In 1727, Bessler last announced the construction of a wheel because 's Gravesande promised to inspect it again. It is still unclear whether such an investigation took place. Landgrave Prince Karl died in 1730, so that Bessler no longer had any protection except through his son. On May 1, 1733, Bessler destroyed the most important records of the construction of the wheel. In 1738 Bessler announced further inventions: submarines, windmills that are independent of the wind direction and autonomous organs.

Towards the end of his life, Bessler founded a religious community, the so-called “Orffyreaner”, whose main goal was the reunification of Catholics and Protestants. As far as can be ascertained today, this religious movement cannot be associated with his bike. In 1745 Bessler died after falling from a windmill. He took his secret with him to the grave, but left 143 technical sketches that his widow published after his death.

The time after Bessler

After the inventor's death, it took 36 years for a historian to bring the story of Bessler back into general memory. The main source at that time, however, was the accusation made by Bessler's former maid. In the German-speaking area, Bessler is largely unknown, in contrast to the English-speaking area, Denmark and the Benelux countries.

The Bessler bike

In view of the fact that the Bessler wheel contradicts fundamental laws of physics, the logical conclusion to be drawn is that it was a well-hidden fraud that no one was able to discover. Bessler himself gave in 1719 on pages 19-21 and 74-76 of his book Das Triumphirende Perpetuum mobile Orffyreanum hints on how it works. Here he was referring to gravity. The following are two copies of Bessler's work Das Triumphirende Perpetuum mobile Orffyreanum . Some of the transcripts have been adapted to today's spelling, but not to today's terminology:

“The internal structure of this tympani or wheel is of such a nature that several ad legus motus mechanici, perpetui a priori, id est scientifice demonstrabilis disposed weights have to continue incessantly after receiving a single rotation, or after an impressed force of the swing That is to say, for a long time the whole structure of your esse retains without some further aid or assistance from external forces of movement which would have required a resubstitution. Such other automatons as clockworks, springs and attached or wound weights can be found. Because this predominance of mine is not attached, nor an extra mechanism, or only to be confirmed, like external Moventia, which by means of their gravity have to continue the motum or revolution as long as the strings or chains to which they are attached allow it: but it are these weights themselves the perpetual motion machine, or partes essentiales & constitutive of the same, which have their vim & nisum progrediendi, received from the Motu universi, in themselves and have to exercise infinitely (as long as they remain apart from the centro gravio) after they are in such a housing , or scaffolding are enclosed and coordinated with one another, so that they not only never reach an equilibrum or puntus quietis in front of them, but are constantly looking for the same, and attached in their admirable flight according to proportions both their own size and their case size, still others from outside to the shaft or Axin of her Vorticis verticalis move and drive applied loads n must. "

“The sans reprise, however, expresses so much that it is not a clockwork which has to be driven for as long as it may by winding springs (elateres) or weights, as has already been amply explained above; Because such machines, which are driven by wind, water, weights and springs to be pulled up (should it be possible for many years to happen together) do not have the principle motus in, but extra se, are not per se mobile, or moventes, but, but per accidens: in such a way that the motus is not peculiar to the machinis themselves, but their accidenti and, in the absence of it, the machine itself, not to mention that they should move a dust, which is why they cannot otherwise be called abusive perpertuo mobiles, because only their moves accidentale is such, just as in my work I should call the attached water snail, pounder and stone box such. Because they are driven by the above-described cause of the said masses, quod durantem materiam the power to move and to be able to drive something is what makes up the machine, but which the scaffolding is nothing more than another he pile of matter is and has lost all its crass. However, the delay or inhibition of the machine, which occurs through excessive external force, is an accident morale, namely if one does not want to let the machine run for a longer period of time without need ”

Bessler himself described how it worked with cylindrical weights weighing four pounds (≈ 2 kg), whereby two weights are said to have worked in pairs and so the wheel is said to have been constantly in a state of imbalance. Ultimately, Bessler took his secret with him to the grave; the exact function of the Bessler wheel remains unknown.

Works (selection)

- Thorough report of the Perpetuo ac per se mobili happily inventoried by the anitzo zu Merseburg Mathematicum Herr Orffyreum. Leipzig 1715

- Apological Poetry , o. O. 1717 ( digitized version )

- New message from the curious and well-established Lauff rehearsal of Orffyrean… Perpetui mobilis , Leipzig 1718 (full text on Wikisource )

- The Triumphant Perpetuum Mobile Orffyreanum . Kassel 1719 ( digitized version )

- The right-believing Orffyreer: or the unity of the divided Christians in matters of faith , Cassel 1723

- Kurtz composed and irrevocable epitome of the purest Christian religion . Carlshaven 1724

- The re-invented Orffyrean ship . o. O. 1738

literature

- Niels Brunse: The amazing equipment of Mr. Orffyreus . Roman, Munich 1997, ISBN 978-3-630-62119-7

- Gustav Frank: Orffyré, Johann Ernst Elias . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 24, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1887, p. 418 f.

- Rupert T. Gould: Oddities - a book of unexplained facts . London 1928

- Joachim Kalka: Phantoms of the Enlightenment. Of ghosts, swindlers and the perpetual motion machine . Berenberg, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-937834-15-3

- Tibor Rode: "The wheel of eternity". Roman, Lübbe, Cologne 2013, ISBN 978-3785724682

Web links

- Literature by and about Johann Bessler in the catalog of the German National Library

- Images of Bessler's machine

- Website of the Bessler biographer John Collins

- Biography of Johann Bessler on besslerrad.de

- Video of a rotating replica of the Bessler wheel

Individual evidence

- ↑ Zedler gives a diameter of 2.5 Leipzig cubits and a thickness of 4 inches. ( PERPETUUM MOBILE. In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 27, Leipzig 1741, column 537-545.) This corresponds to 1.41595 m or 9.4396 cm (for conversion cf. Peter Langhof et al .: coins, weights and measures in Thuringia - aid to the holdings of the Thuringian State Archives Rudolstadt. (PDF; 475 KB): . thueringen.de 2006, accessed on September 13, 2019 . ).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bessler, Johann |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Orffyreus, Orrfyre; Bessler, Johann Ernst Elias |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German inventor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1681 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Zittau |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 30, 1745 |

| Place of death | Furstenberg |