Letters to the Chinese Past

Letters in the Chinese Past is a letter novel by Herbert Rosendorfer that appeared in 1983 and soon became a bestseller.

action

With the help of a "time travel compass" (a kind of time machine ), the novel's protagonist , a Chinese Mandarin named Kao-tai from the 10th century , moves into the present and spans a thousand years to get to know modern China. However, since he did not take the rotation of the earth into account due to his static geocentric worldview , he ends up much further west: in the state of Ba Yan ( Bavaria ), in its metropolis Min-chen ( Munich ). He tries to get used to it there and begins to learn the German language (with the help of a history professor with whom he befriends and who accommodates him). As he soon notices, however, the differences between then and now are not easy to bridge. He finds the dirt and noise of the new era in particular, but also the equality of women and the hectic pace of daily life, a chilling culture shock. So he involuntarily falls from one adventure to the next.

During his eight-month stay (that is how long he has to stay in Munich, since his time compass is programmed for exactly this time until his return trip), he reports in a total of 37 letters to his best friend Dji-Gu in the Middle Kingdom of his experiences with the "bignoses", describes his experiences with their technical achievements on the one hand and their uncultivated customs on the other.

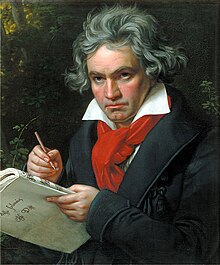

In doing so, he tries - for the modern reader - in an often amusingly cumbersome way to describe all the things and processes that must appear incomprehensible to him at first; For example the automobile, which he initially called the “demon 'ten wild boars” because of its terrifying appearance, or the electric light, the toilet, the money, a sauna, the Munich Opera and Pinakothek , a striptease bar and that Oktoberfest . Few things are really admired by Kao-tai, much criticized, some are described with disgust. The classical music of Mozart and Beethoven in particular has received an almost unreserved positive response . The tingling sparkling wine and the revealing love of the twice divorced teacher Pao-leng (Agatha Pauli) also reconcile him with the terrible future, although the latter of his beloved Shiao-shiao (who at first appears to be a courtesan , but is in In the course of the novel turns out to be a cat) at home cannot hold a candle to it. Otherwise he sees the world through the eyes of the philosopher he admires, Confucius , who also has the right answers for the phenomena of modern times (economy, politics, environmental protection, education) and questions of ethics and literature.

The author sometimes used his own friends and acquaintances as a template for his characters. In the letter about a visit to a court building in particular, several real lawyers appear with recognizable names that have been alienated from Chinese. People from contemporary history are mentioned in the same way, e.g. B. Federal Interior Minister Friedrich Zimmermann with his perjury affair.

shape

In a socially critical and imaginative manner, Herbert Rosendorfer not only targets the manners and conditions of the 1980s in the Federal Republic of Germany, but also comments on capitalism, communism, economy, ecology, religion and philosophy, but above all the general blind and egotistical belief in progress and, closely related to our schizophrenic relationship to the phenomenon of time. So he lets the reader - through the eyes of his protagonist , who is extremely distant in terms of time and space - look at himself with astonishment and at what seems all too natural to us today.

The fact that this seldom happens without comedy is not least due to Kao-tai's flowery language, in particular to his Mandarin politeness, which is overflowing with ritualized and exaggerated phrases; z. B. when he addresses a cleaning lady as the “tall flower of the house” and “fragrant begonia with the moon face” and then says of himself: “The worthless worm Kao-tai greets you reverently and wishes you a honey-soaked summer morning.” Or when, in a similarly humble manner, he reports to his lover on the phone: "Here I speak, your worthless servant and servant Kao-tai, the filthy Mandarin, worth no more than to be driven off your lofty threshold at your feet."

Formally, Rosendorf’s book borrows from the Persian Letters of the French enlightenment philosopher Montesquieu . There are also parallels to the cultural criticism in the fictional speeches of a South Sea chief in The Papalagi . Montesquieu is specifically mentioned in the Letters to the Chinese Past . As it were self-ironically, the author lets his protagonist recognize the parallelism of the two works and ask about the effect of those letters. When Kao-tai found out that the response to Montesquieu had been very low, he decided - paradoxically unlike its author - not to waste his own time “writing a book for the bignoses [...] I stop the wise men from the apricot hill [ie to Confucius]: 'The master said: To attack strange doctrines is pernicious.' "Even when at the end of the novel his patron, Professor Schmidt (Shi-shmi), urged him to write down his experiences for posterity, since they are “of inestimable value to the bignoses”, he categorically rejects this request: “I know what would happen to the little book, the writing of the enigmatic Kao-tai: the bignoses would read it; when it comes up they would read it carefully. They would nod in agreement and then turn to what they consider the seriousness of life. "Resigned and thus indirectly emphasizing the humorous intention of the letter novel, the author sums up (in the words of his protagonist):" Against this seriousness of life not to arrive. "

continuation

A continuation of the letters into the Chinese past was published in 1997 under the title The Great Turnaround . When Kao-tai fell victim to an intrigue by a chancellor named La-du-tsi in his home country, he used his time machine like an emergency anchor, escaped a death sentence and ended up - 15 years after his first trip - in the now reunified Germany . He ends up in the Cologne Carnival ; then he ended up in Leipzig and other places in the new federal states . He is robbed several times, Mr. Shi-Shmi dies of an illness (after a Catholic priest Bez-wi-seng - obviously Fritz Betzwieser - still donated the anointing of the sick to him in the hospital ) and Mrs. Pao-leng has long since found another man. Kao-tai also flies to New York and is shocked there by the pronounced contrast between rich and poor. On the return flight he met Franz Beckenbauer . After a monk clears up the intrigue in his homeland, Kao-tai travels back to China.

literature

- Herbert Rosendorfer: Letters in the Chinese Past . 24th edition. German Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-423-10541-0

- Herbert Rosendorfer: The big turnaround: New letters in the Chinese past . 1st edition, Kiepenheuer & Witsch , Cologne 1998, ISBN 978-3462026320

Individual evidence

- ^ Herbert Rosendorfer, Letters in the Chinese Past , dtv, Munich (1993), page 73.

- ^ Herbert Rosendorfer, Letters in the Chinese Past , dtv, Munich (1993), p. 108.

- ^ Herbert Rosendorfer, Letters in the Chinese Past , dtv, Munich (1993), page 216.

- ^ Herbert Rosendorfer, Letters in the Chinese Past , dtv, Munich (1993), page 273.

- ↑ at Kiepenheuer & Witsch

- ^ FAZ.net / Walter Hinck : Review