Buddhism in Mongolia

The Buddhism in Mongolia is a Tibetan embossed Buddhism (see Lamaism ).

In the 13th century, in the time of Genghis Khan , the Mongols followed Tengrism , a shamanic belief system that combined the worship of ancestors with that of heaven as an overarching cosmos. It was not until the 16th century that Buddhism came from Tibet to Mongolia, became the state religion and flourished there for 200 years.

Influences

Buddhism

The Tibetan Buddhism , the elements of the Mahayana - and Tantric schools of Buddhism combined with traditional Tibetan healing rituals, the general Buddhist target shares of individual salvation from suffering and the cycle of eternal rebirth. Buddhist deities occupy the center of a well-populated polytheistic pantheon of subordinate deities, hostile, converted, and transformed demons , wandering spirits, and holy people, reflecting the folk religions of the areas into which Buddhism had invaded.

Tantrism

The Tantric originate secret techniques of meditation and the variety of sacred images, slogans and gestures. Religion is increasingly taking steps from the concrete to the abstract symbol. A ritual that a normal shepherd perceives as a direct exorcism of the disease demons is interpreted by an older monk as a representation of conflicting tendencies in the sense of a meditating ascetic.

Mongolian Buddhism

Mongolian Buddhism now combined the colorful folk ceremonies and healing rituals of the masses with the study of the secret doctrine of the monastic elite. In contrast to the other schools, the "yellow sect" Gelugpa emphasized monastic discipline, the use of logic and formal discussion as an aid to enlightenment. She combined the basic Buddhist doctrine of reincarnation with the tantric thought that the Buddha state can be achieved during a person's lifetime.

A caste of leaders emerged who were revered as leaders who had had Buddhism and reincarnation . These leaders, called incarnated or living Buddhas, had worldly power and ran a body of ordinary monks or lamas (from the Tibetan title of bla-ma, "the honored"). The monks were supported by the laity, who thus acquired religious merit and instruction from the monks in the fundamentals of the faith and in the monastic services of healing , prophecy and burial .

Buddhism and Buddhist monasticism have always played significant political roles in Central and Southeast Asia , and the Buddhist community of Mongolia was no exception. Church and state supported one another, and the doctrine of reincarnation made it easy for the living Buddhas to be discovered in the families of the ruling Mongolian nobles.

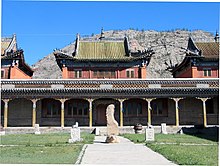

Mongolian Buddhism is a monastic religion . At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were 583 monasteries and temple complexes in Outer Mongolia . Almost all Mongolian cities arose near monasteries. Yihe Huree, later known as Ulan Bator , was the seat of the highly respected living Buddha of Mongolia ( Jebtsundamba Khutuktu , alias Bogdo Gegen , later Bogdo Khan ), who ranked third in the spiritual hierarchy after the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama . About 13,000 and 7,000 monks lived in the two largest monasteries; their Mongolian settlement name to outsiders was Urga, Yihe Huree - Great Monastery .

history

In 1578 invited Altan Khan , a Mongol military leader who had the ambition to unite the Mongols and Genghis emulate, the head of the spreading yellow sect of Tibetan Buddhism at a summit one. They formed an alliance that gave Altan the right and religious legitimation for his imperial claims and that placed the Buddhist sect under protection and patronage. Altan gave the Tibetan leader the Mongolian title of Dalai Lama , which his successors still hold on to today. Altan died soon after, but the yellow sect spread throughout Mongolia in the following century. Monasteries were built all over Mongolia, often on trade routes, migration routes or the summer pastures, where shepherds gathered for shamanistic rituals and sacrifices. The Buddhist monks waged a protracted struggle against shamanism and took over from it the role of healers , fortune tellers and tax recipients.

Over the centuries the monasteries acquired riches and secular dependents; they gradually increased their wealth and power, which resulted in a decline on the part of the Mongolian nobility. Shepherds dedicated themselves and their families to monastic service either out of piety or in an effort to escape the arbitrary demands of the nobility. In some areas, the monasteries and lamas (of which there were 140 total in 1924) were also the secular authority. In the 1920s there were about 110,000 monks, including children, about a third of the male population, although large numbers lived outside the monasteries and not by their rules. About 250,000 people, more than a third of the total population, either lived in areas administered by monasteries or worked in monasteries. With the end of Chinese domination in 1911, the Buddhist community and its clergy were seen to be the only existing political system, and the autonomous state consequently took the form of a weakly centralized theocracy , led by Jebtsundamba Khutuktu in Yihe Huree, later Ulaanbaatar .

Until the twentieth century, Buddhism was part of Mongolian culture, and the population willingly supported llamas and monasteries. Foreign observers often had a negative opinion of the Mongolian monks, who they perceived as lazy and corrupt, which the Mongolian people saw differently.

Persecutions from 1928

After the Mongol Revolution of 1921, a nominally communist party had taken power in the country. However, the party was initially by no means openly anti-religious, the Jebtsundamba Khutukhtu remained the official head of state until 1924, and leading politicians in the first years after 1921 were lamas (such as Bodoo) or even high rebirths (such as Jalkhanz Khutagt Damdinbadsar).

As a result, the Buddhist monasteries initially retained their overwhelming influence in the country. Most of the population was very religious, the monasteries had a monopoly on education and health care, and they controlled a large part of the national wealth. Some parts of the country were even administered directly by monasteries.

The first large-scale attack on religion took place in 1928–1932, accompanied by campaigns to collectivize livestock and nationalize transport and trade. The monasteries were subjected to existential taxes, the herds of cattle, which formed the main source of income, were nationalized. Collectivization and nationalization, however, turned out to be failures and led to bloody uprisings in which both lamas and lay people participated. They were finally withdrawn in 1932. In 1934 the party numbered 843 Buddhist centers and around 3000 temples of various sizes. According to the party , the annual income of the monasteries was 31 million tugrik , while the national income was 37.5 million tugrik. In 1935 the proportion of monks in the adult male population was 48%.

In 1937, in connection with Josef Stalin's Great Terror and the stationing of Soviet troops in Mongolia, almost all monasteries were closed and destroyed. The persecution, which also affected the state apparatus and the army, killed 30,000 people, including 18,000 lamas. The remaining monks were forcibly secularized. The usual pretext for the persecution was the alleged conspiracy of the persecuted with the Japanese against the Mongolian People's Republic .

A dedicated museum dedicated to the politically persecuted was set up in the mid-1990s. Among other things, it documents excavations of human remains from mass graves.

Buddhism since 1944

In 1944, a monastery in Ulan Bator, the Gandan Monastery , was reopened. For a long time it was the only single purpose monastery in the country. Otherwise the practice of religion was practically forbidden. Some old monasteries survived as museums; the Gandan Monastery served as a living museum and a tourist attraction. His monks included a few young men who had completed a five-year course, but whose motives and mode of selection remained unknown to Western observers.

The party apparently felt that Buddhism no longer posed a challenge to their rule and that it had played such a part in the history, tradition, art and culture of the country that a complete removal of knowledge about religion and its practice would damage the modern Mongols national identity would cut off from their past. Some elderly former monks were hired to translate Tibetan-language manuals on herbs and traditional medicine. Government spokesmen have now described the monks at Gandan Monastery as "doing useful work".

After the political turning point in 1991, Mongolian Buddhism flourished again. The Gandan Monastery became the focal point for Mongols as well as Russians, Buryats, Kalmuks and Tuvins as well as the inhabitants of the autonomous Chinese Inner Mongolia . 140 monasteries with around 2500 monks today have been reconstructed. In 1991, the Dalai Lama appointed the Tibetan Jampel Namdröl Chökyi Gyeltshen as the Mongolian spiritual leader and incarnation of the leader Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, who died in 1924, and inaugurated a number of monasteries. In 2001, Mongolian was used as the liturgical language instead of Tibetan for the first time in a monastery . Buddhist schools from other Asian countries are also helping to rebuild religious life in Mongolia.

literature

- Michael Jerryson: Mongolian Buddhism: The Rise and Fall of the Sangha. Silkworm, Chiang Mai 2007.

- Owen Lattimore, Fujiko Isono: The Diluv Khutagt: Memoirs and autobiography of a Mongol buddhist reincarnation in religion and revolution. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1982

- Larry William Moses: The Political Role of Mongol Buddhism. Indiana University Uralic Altaic Series, Vol. 133, Asian Studies Research Institute, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, 1977

- Late forms of Central Asian Buddhism: the old Uighur Sitātapatrā-dhāraṇi. Ed., Trans. and come by Klaus Röhrborn and Andras Róna-Tas. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005.

- Giuseppe Tucci , Walther Heissig : The religions of Tibet and Mongolia. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1970.

- Vesna A. Wallace (Ed.): Buddhism in Mongolian History, Culture, and Society. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-0-1902-6693-6

- Michael Weiers (Ed.): The Mongols. Contributions to their history and culture. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1986.