Codex Sangallensis 911

| Repository | St. Gallen Abbey Library |

| Place of origin | unknown |

| Time of origin | End of the 8th century |

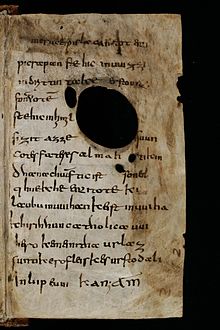

| Writing material | parchment |

| scope | 323 pages |

| format | approx. 17 x 10.5 cm |

| language | Old High German , Latin |

| Number of lines | 14-21 |

| font | several hands, Alemannic minuscules |

The Codex Sangallensis 911 is a collective manuscript with an Abrogans script , the St. Gallen Paternoster and the Credo , which together are among the oldest Old High German sources and were created at the end of the 8th century.

General Information

The Abrogans manuscript is now kept in the St. Gallen Abbey Library. This is a Latin language dictionary with Old High German translations, which was supplemented by a Paternoster (Our Father) and a Credo (creed) in Old High German after it was written.

The collective manuscript is called Abrogans-Handschrift, based on the first word of the first part of the manuscript (the dictionary): abrogans = dheomodi (modest, humble).

All three texts have been written down by several scribes on parchment that is partially poor and full of holes in Alemannic minuscule . The use of inferior parchment indicates that the manuscript was intended for internal use rather than the public. It is believed to have reached St. Gallen from the Alsace region in the first half of the 9th century .

content

Abrogans

The dictionary contains 3,239 Old High German and 3,670 Latin words, although the German translations are incorrect. The glossary thus serves as a source for knowledge of the oldest German language, as it also contains 700 words that are otherwise no longer present in any other Old High German text. No less than twenty hands have written the abrogans on inferior parchment. This indicates that the handwriting was intended more for internal use and probably served as a rhetorical exercise in style. Except for a few initials , such as at the beginning of the text, the handwriting is kept quite unadorned, which in turn indicates the assumption that the document was not intended for the public. Probably in the old Bavarian diocese of Freising , under Bishop Arbeo , the dictionary was finally 'translated' into German in the second half of the 8th century. Both the Latin headwords and their Latin renditions were glossed with Old High German equivalents. The German translations do not appear interlinear as usual, but next to the terms.

No copy has been preserved from the time the glossary was created in the 8th century. There are three more recent manuscripts of the "Abrogans Deutsch" in Paris ( Bibliothèque nationale de France , Ms. lat. 7640, Bl. 124r-132v), Prague ( National Library of the Czech Republic , Cod. XXIII.E.54, Bl. 22r- 47v) and Karlsruhe ( Badische Landesbibliothek , Cod. Aug. perg. 111, Bl. 76r-90r). In relation to the manuscript from St. Gallen, the research deals on the one hand with the question of whether one or more scholars worked on the Old High German translations and, if there were several translators, whether they came from the same language area. On the other hand, it is questionable whether the words are in their basic grammatical form in the glossary or whether the expressions were not taken from existing texts when the handwriting was written, which then means that the dictionary was used for explicit text explanation. Linked to this is the question of whether the St. Gallen Abrogans is a "secondary Bible glossary" that took over glossary groups from existing glossaries.

paternoster

(true to line playback)

| Old High German | Latin | New High German |

|---|---|---|

| Fater our thu | Father noster, qui | Our father who you |

| pist in himile uuihi | it in caelis: sanctificetur | are in heaven, sanctified |

| namun dinan. | noun tuum. | become your name; |

| qhueme rihhi | Adveniat regnum | your kingdom come to us; |

| din uuerde uuillo diin | tuum. Fiat voluntas tua, | Your will will happen, |

| so in himile sosa in erdu. | sicut in caelo, et in terra. | as in heaven, also on earth! |

| prooth our emez- | Panem nostrum cotidianum | Our daily bread |

| zihic kip us hiutu oblaz | da nobis hodie. Et dimitte | give us today; and forgive |

| us sculdi unseero | nobis debita nostra, | our fault |

| so uuir obla- | sicut et nos dimittimus | as do we |

| zem us scul- | debitoribus nostris. | forgive our debtors; |

| dikem enti ni | Et ne | and |

| unsih firleiti in kho- | nos inducas in tentationem, | do not tempt us |

| runka uzzer losi un- | sed libera | but deliver us |

| sih fona ubile. | nos a malo. | of the evil. |

Despite the centuries that lie between the development of Old High German to today's New High German , the Old High German Paternoster is easy to understand, also due to the familiarity of the Our Father in the church. The few changes can be seen in the word 'khorunka' (= temptation, lines 13f.), Which has disappeared and 'emezzihic' (lines 7f.) With its change in meaning from the earlier 'daily' to the now common 'industrious'. There are also a few words with full Endsilbenvokalen present, over the following centuries weakened in Middle High German (rihhi, Erdu) and some terms of the sound shift of Südalemannischen are marked. It is unclear whether the translation refers to a template. A dating even further back than the 8th century is not assumed by research due to the language level and tradition. The translation is often viewed as a failure in research, which can be stated at a few points. For example, 'uuihi namun dinan' (lines 2f.) (= Hallowed be your name) is translated from the Latin passive voice , as in today's German Our Father, not passively, but actively. The question arises whether this is really a translation error or a deeper theological thought, since only God, the Almighty, can sanctify his name.

Creed

(true to line playback)

| Old High German | Latin | New High German |

|---|---|---|

| kilaubu | Creed | I think |

| in excrement fat (er) almah- | in Deum, Patrem omnipotent, | to God the Father Almighty, |

| ticum ki- | Creatorem | the creator |

| scat himiles | caeli | Of the sky |

| enti erda enti in Ih (esu) m | et terrae. Et in Jesus | and the earth. And to Jesus |

| christ sun sinan aina- | Christ, filium eius unicum, | Christ his only begotten Son |

| cun unsanely | Dominum nostrum: | our Lord, |

| the inphangan is fo- | qui conceptus est de | received by the |

| na uuihemu keiste | Spiritu sancto, | Holy Spirit, |

| kiporan | natus | born |

| fona mariun | ex Maria | of the Virgin Mary |

| macadi euuikeru | Virgin, | |

| kimart red in ki- | passus sub | suffered from |

| uualtiu pila- | Pontio Pilato, | Pontius Pilate |

| tes | ||

| in cruce pislacan dead enti | crucifixus, mortuus, et | crucified, died and |

| picrapan stand in uuizzi | sepultus, descendit ad inferos: | buried, descended into the realm of death |

| in threesome take destroyed | tertia the resurrexit | rose on the third day |

| fona tote (m) | a mortuis; | from the dead, |

| stand in himil | ascendit ad caelos; | ascended to heaven; |

| sizit az zesuun | sedet ad dexteram | he sits on the right |

| cotes fateres almahtikin | Dei patris omnipotentis: | God the Almighty Father: |

| dhana chui (m) ftic is sonen | inde venturus est iudicare | from there he will come to judge |

| qhuekhe enti tote ki- | vivos et mortuos. Creed | the living and the dead. I think |

| laubu in uuihan keist in uuiha | in Spiritum sanctum, sanctam | to the Holy Spirit, the holy one |

| khirihhun catholica uui- | ecclesiam catholicam, sanctorum | catholic church, community |

| hero kemeinitha urlaz | communionem, remissionem | of saints, forgiveness |

| suntikero fleiskes urstodali | peccatorum, carnis resurrectionem, | of sins, resurrection of the dead |

| in liip euuikan; Amen) | vitam aeternam. Amen. | and eternal life. Amen. |

The translation of the Credo, like that of the Paternoster, is regarded as incorrect. In research, one deals primarily with the question of whether the well-known Latin symbolum Apostolicum served as a template for the Credo . At the same time there is also the assumption that the Latin model of the Credo, like that of the Paternoster, comes from northern Spain or western Gaul and was brought to the east and to St. Gallen by Irish monks.

literature

- Gustav Must: The St. Gallen Credo . In: Karl Hauck (ed.): Early medieval studies. Yearbook of the Institute for Early Medieval Research at the University of Münster . Volume 15. Berlin 1981, pp. 371-386.

- Gustav Must: The St. Gallen paternoster . In: Hans-Gert Roloff (Ed.): Files of the 5th International Congress of Germanists Cambridge 1975 . Leonard Forster. Issue 1, Bern 1976, pp. 396-403.

- Peter Ochsenbein: The oldest German book with the oldest native speaker 'Pater noster' - The 'Abrogans' handwriting with the' St. Gallen Our Father ' . In: Cimelia Sangallensia. Hundreds of treasures from the St. Gallen Abbey Library , Karl Schmuki, a. a. St. Gallen 2000, p. 32f.

- Stefan Sonderegger: Old German in St. Gallen . In: Peter Ochsenbein (Ed.): The St. Gallen Monastery in the Middle Ages. The cultural bloom from the 8th to the 12th century . Darmstadt 1999, pp. 205-222.

- Stefan Sonderegger: St. Gallen Paternoster and Credo . In: Kurt Ruh u. a. (Ed.): The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . Volume 2. 2nd edition. Berlin 1980, pp. 1044-1047.

- Jochen Splett: Abrogans German . In: Kurt Ruh u. a. (Ed.): The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . Volume 2. 2nd edition. Berlin 1978, pp. 12-15.

- Jochen Splett: The Abrogans and the use of Old High German writing in the 8th century . In: Herwig Wolfram, Walter Pohl (Hrsg.): Types of ethnogenesis with special consideration of Bavaria . Volume 1. Vienna 1990, pp. 235-241.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Quoted from: Jochen Splett: Der Abrogans and the use of Old High German writing in the 8th century. In: Herwig Wolfram, Walter Pohl (Hrsg.): Types of ethnogenesis with special consideration of Bavaria . Volume 1, Vienna 1990, p. 240.

- ↑ busy . duden.de

- ↑ Peter Ochsenbein: The oldest German book with the oldest native speaker 'Pater noster' - The 'Abrogans' handwriting with the' St. Gallen Our Father ' . In: Karl Schmuki, u. a .: Cimelia Sangallensia. Hundreds of treasures from the St. Gallen Abbey Library . St. Gallen 2000, p. 32 f.

- ↑ Gustav Must: The St. Gallen Credo . In: Karl Hauck (ed.): Early medieval studies. Yearbook of the Institute for Early Medieval Research at the University of Münster . Volume 15. Berlin 1981, pp. 371-386