Crow's first lesson

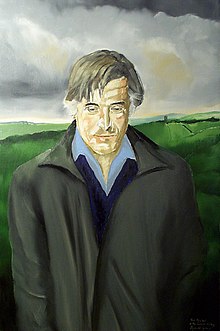

Crow's First Lesson is a poem by the English poet and writer Ted Hughes , which was first published in 1970 by the London publisher Faber & Faber as part of the Crow- Chants cycle ( Crow. From the Life and Songs of the Crow ) .

The American edition of the Crow songs from 1971 by Harper & Row Verlag in New York and the English second edition from 1972 were supplemented by seven further poems. Since then, several new editions have been published by different publishers.

The cycle of the Crow poems is considered to be one of Hughes' most ambitious poetic projects, in which he makes the first large-scale attempt at creating modern myths .

A German first transmission of Crow -Gedichtsammlung of Elmar leg in 1986 under the title Crow: From the Life and the songs of the Crow - poems = Crow: From the Life and Songs of the Crow in a bilingual edition in Klett-Cotta issued the 2002 was reissued. Crow's First Lesson has since been reprinted several times in various Hughes poetry collections and various other anthologies.

Interpretative approach

Although Hughes' poem is written in free rhythms, the 18 lines are divided into different stanzas in terms of the printed image . The first two stanzas of four lines each, which are also completed in terms of content, are followed by two stanzas of five and four lines each, which together with the final line in the printed image also form a thematic unit.

The two initial attempts of God to teach the crow that was just born to speak and, above all, the word "love", are unsuccessful; the following third attempt leads to final failure. In terms of language, the poem contains a report in the Er form, which is brought to life and dramatized through direct speaking . Significantly, however, direct speech is limited exclusively to God; Crow, as a disobedient student, is in no way capable of any verbal utterance and can only pry open.

The vocabulary used is emphatically simple; nevertheless carry numerous distinctive onomatopoeic ( crash , zoom , convulse , retch ) and prepositional verbs ( zoom out , bulb out , drop over , fly off ) help to enhance the vividness of poetic representation considerably. In the sentence structure, the syntactic secondary orders predominate at the beginning with the frequent use of the rhetorical stylistic device of the syndeton ( "Crow gaped, and the white teeth flashed ..." ), while the last three lines are clearly distinguished from it by the use of the asyndetone . The deliberate use of a variety of stylistic devices clearly shows the rhetorical intentions of the author, which shape the entire linguistic style of the poem. This rhetorical will to express itself is clearly recognizable, especially in the emergent use of repetitions and rows for the purpose of intensifying and intensifying the representation.

The repetitions of the words of God and the stereotypical reaction of the crow to them ( “Crow gaped” ) not only emphatically illustrate the lyrical framework, the threefold language attempt , but also emphasize in connection with the series the increase in the effects of the divine language experiment. After the two- fold “Crow gaped” in the first two stanzas, the climax is raised in line 10 : “Crow convulsed, gaped, retched” .

The threefold repetition to intensify and expose the failure of God's efforts not only forms the decisive formal pattern of the poem, but is also reflected in the content. Hughes says elsewhere that the biblical God is just as far removed from the Creator of the world as everyday English is from reality. From his point of view, the Christian concept of love is an empty phrase that only obscures the relationship to living reality, but does not reflect it appropriately. This actual reality manifests itself in the figure of Crow , who was not created by God. Therefore, Crow is unable to produce such a distorting utterance.

Instead of the expected linguistic articulation of the word “love”, a great white shark emerges from its wide open beak and plunges into the sea with a clap. Hughes repeatedly uses this pictorial trope in his poetic work as a metaphor for actual reality and the natural laws governing killing in order to survive, for example in the poem Crow on the Beach , where it says: “When the smell of the whale's den, the gulfing of the crab's last prayer, / Gimletted in his nostril / He grasped he was on earth " .

In Hughes' poem Logos from Wodwo , too , the shark, as the epitome of vitality and lust for murder, represents the counter-image to the Christian myth of love, in order to show its hypocritical untruthfulness. In Hughes' eyes, the shark is a wonderful animal that has nothing repulsive about it.

In God's second attempt to get Crow to articulate the word “love”, on the other hand , Crow's throat is filled with flies and mosquitoes that buzz towards their various meat pots. In this way, the supposed Christian universal law of love is enhanced not only by the triad (triad of "a bluefly, a tsetse, a mosquito" ), but also by the fact that these animals are parasites and carriers of disease refuted.

The third attempt, which at the same time takes up more space than the first two together, again increases the unpleasant surprise beyond measure, as love here in the human realm is transformed into a caricature . This climax is heralded by the intensely ominous gagging of Crow ; what follows is the image of the enormous, cross-eyed and bubbling head of a man without a body who plopps to the ground. A little later, when Crow vomits again, a female shame drapes over his neck and contracts. Hughes tries once again to use caricature to take the Christian message of salvation ad absurdum and thus succeeds DH Lawrence , who viewed the relationship between the sexes and beyond that the relationship between nature and spirit as a fateful vice that only allows the choice between sexuality as an ominous goal or the ideal destiny as a deadly parasite : “Sex in itself is a disaster: a vice. ... And now we only have these two things: sex as a fatal goal ... or ideal purpose as a deadly parasite. "

In Hughes' poem, the disembodied monstrous head symbolizes the one-sided emphasis on the mind in modern times , which Hughes scourges with biting derision as "enormous surplus of brain" , as in the context of the Crow - Poems for example in the grotesque Crow's Account of St. George .

Similar to Crow's First Lesson , Hughes often combines his criticism of the absolutized spirit and the overpowering science with his displeasure with the idiosyncratic nature of language, which, according to him, stands in the way of an immediate experience of reality and, with its slogans, even brings harm to humanity.

While the head-cackling protests in Crow's First Lesson embodies abstract spirituality, female shame here, conversely, stands for the overemphasis on sexuality. As Lawrence saw, its effects are not life-enhancing for Hughes, but murderous. Taunted with the metaphor of grotesque struggle to the death between the male head monster and the female pudenda Hughes in the three final lines of his poem ultimately again climatically the Christian view of man, which subordinates the unity of body and mind and the sex ratio of the idea of love .

Moreover, the essence of Christian God as embodied love is mocked in two ways. Crows' existence and God's failed attempt to teach and educate not only disavow the Christian conception of love as the law of the world, but at the same time demonstrate the helplessness of God, who, to make matters worse, loses self-control in his powerlessness and begins to curse, but thereby exposes himself and transferred.

As the last line of the poem shows, Crow , the involuntary culprit, who until then was incapable of any human emotion or sensation, was overcome by feelings of guilt for the first time: “Crow flew guiltily off” . In the entire context of the poem, this final line allows only a sarcastic interpretation in the sense of the travesting basic message .

Developmental background

In 1957, in America, Ted Hughes met the sculptor and engraver Leonard Baskin , whose peculiarity is the depiction of crows with disturbing human characteristics. At Baskin's request to add short poems to his engravings, Hughes' first Crow poem, the dramatic dialogue Eat Crow , was written in 1964 . Further preliminary stages to the volume of poetry Crow can be seen in the poems Logos , Reveille , Stations and Theology from the Wodwo collection from 1967. The expansion of the second edition of the Crow poems from 1971 and details about Hughes' plans that became known later indicate the original poetic intention of creating a prosimetric folk tale with further additions and changes, of which, however, only a selection of the chants about Crow were implemented is.

In Hughes' plans there are also allusions to a mysterious mythical being next to and about God, who makes a bet with him and whose creature is Crow . In the present chants of the Crow band, however, such moves are not carried out. However, Crow appears as a troublemaker by whom the Christian God reviled as "man-created, broken-down, despot of a ramshackle religion" (German: "Man-made, broken or failed despotic representative of a ramshackle religion") becomes. Hughes thus chooses the crow as a poetic hero and gives it a croaking voice:

"Screaming for Blood / Grubs, crusts / Anything / Trembling, featherless elbows in the nest's filth" (from: Lineage )

The cover picture of Baskin for the English paperback edition of Crow Gesänge shows a hairless body standing on colossal legs, on which there is a tiny head, but which is armed with an enormous, curved beak: “his mere eyeblink / Holding the very globe in terror ” (German for example:“ the mere expression of his eyes / keeps the whole world in horror ”).

Obviously Hughes, who switched his subjects from English linguistics and literary studies to archeology and anthropology while studying at [University of Cambridge | Cambridge], draws on his knowledge of various myths and legends here . In agreement with other mythical beings, Crow is already stronger in that moment than death, in which he is just born:

"And still he who never has been killed / Croaks helplessly / And is only just born." (From: Crow and Stone )

The world of creation into which he was born is, however, characterized at the same time by the horror and horror of a visionary end time :

"Crow saw the herded mountains, streaming in the morning / ... / And he shivered with the horror of Creation. / In the hallucination of the horror / He saw this shoe, with no sole, rain-sodden / Lying on a moor. / And there was this garbage can, bottom rusted away, / A playing place for the wind, in a waste of puddles. " (From: Crow Alights )

The poem Crow's First Lesson is thematically integrated into this poetic context, which is a parody of the idea of the validity of the Christian virtues of faith, hope and love as the law of the world.

Work history context

Hughes' ambitious poetic endeavor to create large-scale new myths in the Crow poems can be understood as his poetic response to the wear and tear of outmoded conventional forms of life and art, which for him, as before for DH Lawrence, have lost meaning and credibility. For him it is not primarily about removing old rotten "frameworks", but rather examining the question of what people in modern times really believe in and where their actual needs lie. With his ambitious attempt to give expression to a new worldview in the creation of myths in his poems, Hughes goes well beyond the analyzes of the present made by his contemporary colleagues such as Philip Larkin . According to Hughes' own statements, a text only becomes poetic for him when it relates to the essential forces in the world as well as in himself.

Hughes' underlying worldview is about ideas of energy and violence as elementary expressions of life, which he initially sees positively, provided that they are an expression of an energy as a basic given, as already expressed by DH Lawrence in the 1920s Has. According to Hughes' view, this elementary energy can be repressed; however, suppression leads to a kind of "death-in-life". A comparable idea can already be found to some extent in Romanticism and in the 19th century. However, if this energy is not directed in an orderly way, i.e. if it is kept under control through credible views, rituals or conventions, it has an extremely destructive effect.

Hughes' attempt at the poetic creation of myths should be seen against this background: the poetic design and clothing aims to restore the broken reference to vital reality in order to channel and use that dam break of energy and violence that could otherwise be triggered . In his poem Crow's Theology , Hughes shows how the Christian conception of God is being replaced in the consciousness of his hero by a new polytheistic worldview. First, Crow adopts the idea of being loved by God, in the sense of the traditional doctrine of providence , since he believes that otherwise he will drop dead. Happy about this certainty he listens with admiration his heartbeat and noticed that God probably Crow speaks ( "And he did Realized God spoke Crow - / Just what his existing revelation" ). Immediately afterwards, however, his confidence is shaken when he considers that there are countless other beings besides himself, including stones or even ball lead, which destroys so many of his kind. Thinking about the question of which being could speak the silence of the ball lead him suddenly to the thought that there must be two deities, one of which is not only much more powerful, but also the deity of his enemies. Crow's Theology clearly shows how Hughes conceives the Crow myth as a counter-myth to the Christian conception of God.

In the poetic illustration of the Crow poems, Hughes draws a picture of reality that is essentially determined by the experiences of evil and violence, which appear to be specific characteristics of reality. Hughes' attempt to translate the feeling of threat in an experience of the world shaped by violence and destruction into poetic figures and actions is not a completely new undertaking in literary history. Various other poets after 1945 tried to translate similar ideas of the destructive forces in the world into a literary-poetic form, for example the English poet and literary critic Al Alvarez in his 1962 anthology of contemporary Anglo-Saxon poetry, The New Poetry .

In the field of English poetry or literature, the forerunners and models of this poetic orientation also include works that were created significantly earlier historically not only by DH Lawrence, but also by Thomas Hardy as early as the end of the 19th century , who in his poems and sometimes also in novels the conception takes the view that the or rather the world movers are either limited in their power or are cruel. Here, too, good and evil are inextricably intertwined; in Hardy's poem The Sleep-Worker , a mother figure in a universe without God releases the world in a state of trance. In the Hughes Crow episode there are similar worlds of images and ideas in which the Christian God takes on a ridiculously insignificant extra role when he is not even asleep, while Crow and his fellows perform their iniquities or pranks. This is how Hughes' poem A Childish Prank ends with the succinct closing lines “God went on sleeping / Crow went on laughing” .

Text output

- Crow's first lesson . In: Ted Hughes: Crow. From the Life and Songs of the Crow . Faber & Faber, London 1970, 2nd expanded edition 1972, ISBN 978-0-571-09915-3 .

- Crow's first lesson . In: Ted Hughes: New Selected Poems 1957–1994 . Faber & Faber, London 1995, ISBN 978-0-571-17378-5 .

- Crow's First Lesson in Ted Hughes: Crow: From the Life and Songs of the Crow - Poems = Crow: From the Life and Songs of the Crow . Bilingual edition with a translation into German by Elmar Schenkel . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1986, 2nd edition 2002, ISBN 978-3-608-95408-1 .

Audio outputs

- Crow's first lesson . In: Ted Hughes: Crow . Faber Penguin Audiobooks, London 1998, ISBN 978-0-14-086405-2 .

Secondary literature

- J. Brooks Bouson: A Reading of Ted Hughe's 'Crow' . In: Concerning Poetry , 7 (1974), pp. 21-32.

- John Michael Crafton: Hughes's Crow's First Lesson . In: Explicator 46, 1988, pp. 32-34.

- Rainer Lengeler: TED HUGHESCrow's First Lesson . In: Rainer Lengeler (Ed.): English Literature of the Present 1971–1975 . Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, ISBN 3-513-02226-3 , pp. 348-352.

- David Lodge : "Crow and the Cartoons" . In: Critical Quarterly , 13 (1971), pp. 37-42.

- I. Robinson and D. Sims: "Ted Hughes" 'Crow' . In: The Human World , 9 (1972), pp. 31-40.

Web links

- Crow's First Lesson - From Ted Hughes New Selected Poems 1957–1994 - English text edition

- Ann Skea: Ted Hughes and Crow

- The Old Heaven, the Old Earth by Thomas Lask - Review of the volume of poems Crow in the New York Times on March 18, 1971

Original text of the poem

| Crow's First Lesson (Original text, 1970) |

|---|

|

Crow's First Lesson |

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rainer Lengeler: TED HUGHES · Crow's First Lesson . In: Rainer Lengeler (Ed.): English Literature of the Present 1971–1975 . Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, ISBN 3-513-02226-3 , pp. 348-352, here p. 348

- ↑ See Rainer Lengeler: TED HUGHESCrow's First Lesson . In: Rainer Lengeler (Ed.): English Literature of the Present 1971–1975 . Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, ISBN 3-513-02226-3 , pp. 348-352, here p. 350.

- ↑ See Rainer Lengeler: TED HUGHESCrow's First Lesson . In: Rainer Lengeler (Ed.): English Literature of the Present 1971–1975 . Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, ISBN 3-513-02226-3 , pp. 348–352, here pp. 350–352. The passages quoted in the text are taken from the print here.

- ↑ See Rainer Lengeler: TED HUGHESCrow's First Lesson . In: Rainer Lengeler (Ed.): English Literature of the Present 1971–1975 . Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, ISBN 3-513-02226-3 , pp. 348-352, here pp. 351 f.

- ↑ See Rainer Lengeler: TED HUGHESCrow's First Lesson . In: Rainer Lengeler (Ed.): English Literature of the Present 1971–1975 . Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, ISBN 3-513-02226-3 , pp. 348-352, here p. 352.

- ↑ Rainer Lengeler: TED HUGHES · Crow's First Lesson . In: Rainer Lengeler (Ed.): English Literature of the Present 1971–1975 . Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, ISBN 3-513-02226-3 , pp. 348-352, here p. 349 f. See also Neil Roberts: Poetry by Ted Hughes - Crow: from the Life and Songs of the Crow . Available online from the Ted Hughes Society website [1] , accessed June 29, 2017.

- ↑ Rainer Lengeler: TED HUGHES · Crow's First Lesson . In: Rainer Lengeler (Ed.): English Literature of the Present 1971–1975 . Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, ISBN 3-513-02226-3 , pp. 348-352, here p. 349 f. The quoted passages of Hughes' poetry are taken from the print at this point. See also Ann Skea: Ted Hughes and Crow for more details on the historical background and work context . In: The Endicott Studio Journal of Mythic Arts , Winter 2007, available online at [2] , accessed June 28, 2017.

- ↑ See Rainer Lengeler: TED HUGHESCrow's First Lesson . In: Rainer Lengeler (Ed.): English Literature of the Present 1971–1975 . Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, ISBN 3-513-02226-3 , pp. 348-352, here pp. 331ff.

- ↑ See Rainer Lengeler: TED HUGHESCrow's First Lesson . In: Rainer Lengeler (Ed.): English Literature of the Present 1971–1975 . Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, ISBN 3-513-02226-3 , pp. 348-352, here pp. 332f. The text quotations are taken from the print here. The text of the aforementioned poem by Thomas Hardy is available online at The Sleep-Worker at poemhunter.com. Retrieved on June 30, 2017. For the interpretation of this poem by Hardy cf. e.g. Deborah Collins: Thomas Hardy and his God: A Liturgy of Unbelief . The MacMillan Press, Houndmills, Basingstoke, and London 1990, ISBN 978-1-349-11367-5 , pp. 70ff.