Brumadinho dam breach

The Brumadinho dam breach was a mudslide accident in the small Brazilian town of Brumadinho near Belo Horizonte in the state of Minas Gerais on January 25, 2019. The 11.7 million cubic meters of mudslide from the bursting sedimentation basin of an iron ore mine destroyed buildings and facilities on the mine site as well as houses in settlements near the city and killed at least 259 people (as of December 28, 2019). The Paraopeba River ecosystem , into which the mudslide flowed, was considered destroyed. In July 2019, a court sentenced mine operator Vale to pay for all damage caused by the disaster.

The dam

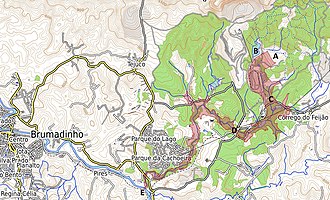

The dam belongs to the Mina Córrego do Feijão , an open-cast iron ore mine owned by the Vale mining company . The dam formed the southeastern wall of a sedimentation basin for tailings , which are muddy fine-grain residues from ore processing.

Construction of the dam began in 1976 and it was raised in ten steps to a final height of 86 m. The individual embankments were around 5 to 8 m high. For the construction initially overburden from mining and then soil ( laterite ) from the area were used, which was compacted, later (in the last six stages) the dried tailings of the sedimentation basin were removed . It consists of 56 percent fine sand, 28 percent silt , 8 percent medium sand and 4 percent clay .

There are at least 790 tailing dams in Brazil. Minas Gerais is by far the state with the most such dams; More than half of the iron ore extracted in Brazil comes from this mining state. Many tailings dams in Brazil lie above cities and settlements and threaten them directly. More than 200 dams in tailings basins in Brazil have officially been identified as having a high risk potential - not because of an unusually high probability of dam breakage, but because of the number of people affected in the event of a disaster and in view of endangered ecosystems. For Brumadinho, too, the potential risk before the accident was rated as high.

Course and consequences

On January 25, 2019, shortly after noon, the dam collapsed completely in several higher and lower areas and shortly afterwards on a broad front. At that time, more than 400 workers are said to have been on the site. The mudslide poured down into the valley at a speed of initially more than 70 km / h and buried everything on its way. Many workers and employees died in the canteen in the area of the administration building below the broken sedimentation basin. A warning system was installed, but it failed, the sirens remained silent. The driver of a dump truck saw the mudslide early about 550 meters from the dam breach and shouted warnings into her radio, so some people were barely able to save themselves. On January 26, 2019, the day after the disaster, 150 people were reported missing. The fire brigade assumed a total of 200 to 300 victims, as other people besides the workers lived in the flooded area. Among other things, a hotel was destroyed and the wagons of a train were hit by mud. A railway bridge was torn down over a length of around 100 meters. Further down the valley, the mudslide destroyed more than two dozen buildings in the Parque da Cachoeira settlement. It made its way for more than 8 kilometers and finally flowed into the Paraopeba River.

The Brazilian army searched for missing persons with around 1,000 soldiers and sniffer dogs. 130 soldiers from the Israeli army were dispatched to the scene of the accident at the end of January 2019 to use sonar devices to search for people in the masses of mud. As a result of the accident, the Brazilian judiciary froze eleven billion reals (approx. 2.6 billion euros) in the accounts of the operator Vale in order to cover possible compensation payments. In addition, the state and the federal state have already imposed initial fines of 81 million euros against Vale.

By February 1, 2019, 110 victims had been rescued and 238 people were still missing. By the beginning of March, 186 fatalities had been rescued, and a further 122 people were missing. On May 7, the number of confirmed fatalities rose to 237, and 33 other people were still missing. On June 5, the count stood at 246 identified fatalities and 24 missing people. The 256th casualty was found on November 22nd. By the end of 2019, a total of 259 fatalities were found, 11 people were still missing.

The dam was checked by TÜV Süd in September 2018 and there were no complaints. An operating license was issued on the basis of this report . On the morning of January 29, 2019, the police searched the TÜV Süd office in São Paulo, provisionally arrested two engineers involved in the report, and confiscated computers and documents. Three employees of the Vale mining company were also arrested.

On January 30, 2019, it was reported that in December 2018 the regional environmental secretariat of the state of Minas Gerais had given the Vale Group a permit to expand mining activity in Brumadinho and to work on the disaster dam that had actually been disused. In the permit documents the safety risk of the dam was given as 4, which means a medium risk. In previous approvals, the dam had been given risk level 6, a higher risk. As a result of the approval, the production of the mine could have been increased by 70 percent. Subsequently, on February 15, 2019, it was reported that the TÜV Süd employees had been released after a week, and that 8 employees of the Vale mining company were arrested instead. Meanwhile, those responsible are being investigated :

"Vale officials insist that it was an accident, but Minas Gerais prosecutors and police are convinced that we are dealing with a willful crime."

The Ministry of the Environment of the state of Minas Gerais in southeastern Brazil revoked Vale's permit for the Laranjeiras Dam . This belongs to an iron ore mine in Brucutu . The company also lost its license for another dam.

About five weeks after the disaster, in early March 2019, Vale boss Fabio Schvartsman resigned from his post for the time being. This step was recommended to the group by the Brazilian public prosecutor's office . On March 14, 2019, it was reported that eleven employees of the Vale Group and two TÜV Süd employees were again arrested because they are suspected of having known about the instability of the dam.

In March it became known that the TÜV Süd report listed a number of deficiencies, but in the end still certified the stability. No as built documents were available for the first six heights of the dam up to a height of 60.5 meters , so the experts noted that they had not been able to finally assess the situation for the construction up to this point. There was also no register in which construction deviations from the plans were recorded. Documents were only available from 2003 onwards for the last four increases. It was also announced that TÜV engineers had already expressed doubts about safety in 2017 and listed deficiencies. When looking at the relationship between the mine operator Vale and TÜV-Süd, there was also a close personal relationship that contradicted the need for an independent assessment of the dam. It can therefore be assumed that both the inspecting authority TÜV and the mining company to be inspected had a mutual interest in continuing to operate the dam.

Legal processing

On July 9, 2019, a court in the state of Minas Gerais sentenced the mining company Vale to pay for all damage caused by the disaster. An exact amount of damage has not been determined because, according to the judge Elton Pupo Nogueira, it cannot yet be quantified. The court upheld the blockade of the company's assets amounting to eleven billion reais (2.5 billion euros) for possible compensation payments.

Vale commented that the court had recognized the company's "cooperation" during the proceedings and wanted to "quickly and fairly" pay for the disaster claims.

In September 2019, a court sentenced Vale to pay compensation to the families of three fatalities, a total of 2.6 million euros.

In November 2019, the Agency for Natural Resources Agência Nacional de Mineração (ANM) alleged that Vale had not reported critical values to the agency two weeks before the disaster of devices for measuring fluid pressure. With a proper report, ANM could have taken precautionary measures and the dam break could have been prevented.

In January 2020, the public prosecutor in Brazil sued the mining company Vale and TÜV Süd. Murder charges were brought against 21 people, including the then Vale CEO Fábio Schvartsman and five employees of TÜV Süd. Previously, internal e-mails from employees of TÜV Süd had become public, in which they expressed strong concerns about the stability of the dam, especially in the upper area of the dam. One employee said that there was actually no certainty of stability, but that as usual, due to massive pressure from the mining company Vale, it would have done so.

Parallels in 2015 and other endangered retention basins

On November 5, 2015, a dam was also broken at a sedimentation basin at an iron ore mine in the same state. The mine operator Samarco had partly owned Vale and the Australian-British group BHP Billiton . 19 people were killed when the dam at Bento Rodrigues broke .

In April 2020, according to the IndustriAll union, the Brazilian government closed 47 vulnerable retention basins in Brazil, more than half of which belong to Vale. 37 of the retention basins are located in Minas Gerais.

Literature on dam stability

- Washington Pirete, Romero César Gomes: Tailings Liquefaction Analysis Using Strength Ratios and SPT / CPT Results. Chapter 3: Case History: Córrego do Feijão Mine - Dam I. In: Soils and Rocks . Volume 36, No. 1, São Paulo 2013, pp. 36–53, ISSN 1980-9743 (PDF; 16.4 MB; English).

See also

Web links

- Brazil's dam disaster. In: BBC News. February 22, 2019. Detailed report with numerous photos.

- Newsletter for the mining company Vale with relating to Brumadinho and other dams (English)

- Satellite images show the spread of the mudslide before and after the disaster earthobservatory.nasa.gov

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d A Tidal Wave of Mud The New York Times, February 9, 2019. With detailed graphics from satellite images on the course of the mudslide.

- ↑ a b Environmentalists: No life in the river after the Brumadinho dam burst . In: Aargauer Zeitung . March 1, 2019; Accessed March 3, 2019.

- ↑ 86 m according to Spiegel, No. 13, March 23, 2019, p. 21. According to Pirete, Gomes, Soils and Rock, Volume 36, No. 1, 2013, p. 40, the maximum height at that time (2013) was 81 m

- ↑ a b c Brazil’s dam disaster BBC News, February 22, 2019.

- ↑ a b c “There are certainly many victims to complain about” tagesschau.de, January 26, 2019.

- ↑ More than 300 people missing: At least 58 dead in a dam break in Brazil. In: RP ONLINE. January 28, 2019, accessed January 28, 2019 .

- ↑ In the meantime 110 bodies recovered. In: deutschlandfunk.de , published and accessed on February 1, 2019.

- ↑ Activists demonstrate at Vale's Swiss headquarters. In: tagesanzeiger.ch . January 30, 2019, accessed on January 30, 2019 : “42 bodies have since been identified. "Unfortunately, it is very unlikely to find survivors," said a fire department spokesman on the television channel Globo News. "

- ↑ Polícia Civil registra 237 mortos identificados após tragédia em Brumadinho Estado de Minas, 7 May 2019.

- ↑ Corpo da 246 a vítima da tragédia em Brumadinho é identificado g1.globo.com, June 5, 2019.

- ↑ Jovem de 24 anos é a 256ª vítima do desastre em Brumadinho identificada; 14 seguem desaparecidos hojeemdia.com.br, 23 November 2019.

- ↑ Brumadinho: mais duas vítimas do rompimento da barragem da Vale são identificadas g1.globo.com, December 28, 2019.

- ^ A dam breach in Brazil: many victims feared. In: tagesschau.de. January 26, 2019, accessed January 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Thomas Fromm, Boris Herrmann, Frederik Obermaier, Uwe Ritzer: "No defects found". Dam burst in Brazil. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung. January 28, 2019, accessed January 28, 2019.

- ^ A dam breach in Brazil: two engineers from TÜV Süd arrested. In: Welt Online . January 28, 2019, accessed January 30, 2019 .

- ^ Matthias Ebert: Police arrest TÜV Süd employees. In: Spiegel online . January 29, 2019, accessed January 29, 2019 .

- ^ Matthias Ebert: Authorities allowed work on the dam. In: tagesschau.de . January 30, 2019, accessed January 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Eight mine workers arrested. In: tagesschau.de . February 15, 2019, accessed February 16, 2019 .

- ^ "No accident": Investigators are looking for those responsible for the dam breach in Brazil. In: nzz.ch . February 18, 2019, accessed February 18, 2019 .

- ↑ Mine disaster in Brazil: TÜV is said to have warned mining company of a possible dam break . In: Spiegel Online . February 8, 2019 ( spiegel.de [accessed March 3, 2019]).

- ↑ Dam break in Brazil: mining company boss offers to resign. In: Spiegel online . March 3, 2019, accessed March 3, 2019 .

- ^ After a dam break in Brazil - detention order for TÜV employees. In: ZDF . March 14, 2019, accessed March 17, 2019 .

- ↑ Dam disaster: Did the German TÜV fail in Brazil? In: Der Spiegel . March 23, 2019, p. 21.

- ↑ Maria Eugenia Trombini, Mario Jorge Junior and Markus Pohlmann: The collapse of the Brazilian dam - a collapse with the TÜV seal. In: HeiGOS blog: Corporate Crime Stories. Max Weber Institute for Sociology, Heidelberg, June 28, 2019, accessed on August 17, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Court convicts Brazilian Vale group after devastating dam break . In: arte.tv , July 10, 2019, accessed on July 10, 2019.

- ↑ a b Serious allegations against dam operators in Brazil. In: orf.at , November 6, 2019, accessed on November 6, 2019.

- ↑ Brazil is suing TÜV Süd for dam breakage , tagesschau.de, 21. January 2020.

- ^ Leo Rodrigues: TUV Süd collusion said to have caused tragedy in Brumadinho . AgênciaBrasil , 2020-01-22.

- ↑ Mudslide kills hundreds. on: orf.at . January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ↑ Christian Russau: Brazil closes 47 retention basins at risk of breaking. April 17, 2020, accessed July 6, 2020 .

Coordinates: 20 ° 7 ′ 10 ″ S , 44 ° 7 ′ 15 ″ W