Dammtor cemeteries

The burial grounds of the inner-city Hamburg parishes or the Jewish community that were outside the Hamburg city fortifications between the Dammtor and the Sternschanze were designated as Dammtorfriedhöfe or also cemeteries in front of the Dammtor . They were laid out during the 18th century and used until the beginning of the 20th century.

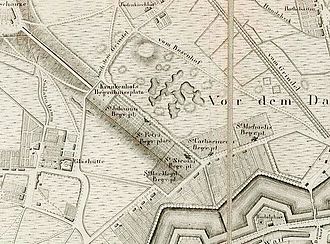

This initially included the cemeteries of the four main churches St. Katharinen , St. Nikolai , St. Petri and St. Michaelis , as well as the two monasteries St. Johannis and Mariae Magdalenen as well as the former " Pesthof " in today's St. Pauli (see map from 1810 ). Later there were additional burial places for the Catholic community (1813), the Reformed communities (1825), the St. Pauli suburban church (1834) and St. Gertrud .

history

While the Jewish cemetery on the Grindel had existed since 1712, the Christian burial places in front of the Dammtor were only created towards the end of the 18th century. The reason for this was the overcrowding and the resulting hygienic grievances in the inner-city church yards. Since the 1770s there have been various attempts by the citizens, in particular by the Patriotic Society of 1765 , to move the tombs outside the city walls. In addition, the Hamburg upper class, in the course of romantic devotion to nature ( Klopstock !), Increasingly went over to having themselves buried in scenic village cemeteries in the vicinity (especially in Hamm , Niendorf and Nienstedten ), which meant that the Hamburg city churches lost significant income . With their park-like layout, these cemeteries also served as models for the new burial grounds.

As the first of the hamburger main churches therefore had St. Jacobi in 1793, a previously-used already as a paupers' cemetery grounds in front of the stone gate as a new burial ground from. The other main churches then negotiated with the Senate to allocate new areas, so that from 1794 the first burial places were set up in front of the Dammtor.

Because the new Dammtor cemeteries were initially decried as "poor cemeteries", Hamburg residents tried to bury the dead within the city wall until this was banned on January 1, 1813 under the French occupation .

In the winter of 1813/14 the occupiers drove 4,000 hamburgers away because they could not find provisions for six more months. In freezing cold they had to leave the city after Christmas night. Many were taken in by the people of Altona , but over 1000 people died as a result of the efforts. In 1815 the Patriotic Society had a tomb designed by Carl Ludwig Wimmel in the form of a sarcophagus built for the victims. In 1841, after the lease for the Ottensener Wiese expired, the parish of St. Nikolai gave a piece of its burial place for the erection of the tomb. The bones of the displaced were transferred and buried here. Since then, the monument has stood in the same place on St.-Petersburger Strasse (formerly Jungiusstrasse).

In the 19th century, the tomb culture flourished in the Dammtor cemeteries. Some wealthy people had their tombs walled up. Many dead were buried in individual graves or in family graves. The tombs were provided with inscriptions, ornaments and symbols or they were simply given the family name or only a first name.

The brotherhoods - as the guild associations of the craftsmen called themselves - were buried in communal graves as well as the "offices". They enclosed the graves with corner stones that were connected with wrought iron chains, but also with bars or hedges.

Dissolution and re-use

After the opening of the new central cemetery in Ohlsdorf in 1877, burials in front of the Dammtor were gradually restricted; the last one took place in 1909.

During the time of National Socialism , a large part of the Dammtor cemetery with their tombs was leveled and redesigned as a parade ground. In return, an open-air museum was set up at the Ohlsdorf cemetery for the Day of Homeland Security , where the artistically most important tombs of the former Dammtor cemeteries are kept in the hedge garden near Chapel 10.

Only the former St. Petri burial chapel from 1802 on St. Petersburger Strasse is preserved. The classicist building, influenced by French revolutionary architecture, based on plans by Johann August Arens, was the first chapel in the cemeteries.

The Planten un Blomen park is located on the northern parts of the former burial grounds, including the zoological garden that was adjacent at the time, and the Hamburg Messe site with exhibition halls on the areas to the south . The name of the street running along the eastern edge of it, "Bei den Kirchhöfen", is still reminiscent of the burial grounds.

See also

literature

- Gertrud Bunsen: About the old Hamburg cemeteries in front of the Dammtor. In: OHLSDORF - magazine for mourning culture, edition: No. 104, I, 2009 of February 6, 2009.

- Jörg Haspel: From the Dammtor cemeteries to the Japanese garden. Destroying history as maintaining tradition? In: Architecture in Hamburg. Yearbook 1991, pp. 102-109.

- Eberhard K Händler: burial grove and crypt. The tombs of the upper class in the old Hamburg cemeteries . Christians Verlag, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-7672-1294-3 .

- Otto Erich Kiesel : The old Hamburg cemeteries. How it came about and how it relates to the urban and intellectual life of old Hamburg , Broschek & Co., Hamburg 1921.

- Barbara Leisner, Norbert Fischer : The cemetery guide. Walks to known and unknown graves in Hamburg and the surrounding area. Christians Verlag, Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-7672-1215-3 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Leisner / Fischer p. 38 f.

- ↑ Leisner / Fischer p. 31 ff.

- ↑ Kellers p. 40, 43.

- ↑ Kellers p. 46 ff.

- ↑ Leisner / Fischer p. 38.

- ^ Ohlsdorf, memories of the beginning

- ↑ List of monuments of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, as of April 13, 2010 (PDF; 915 kB) ( Memento from June 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

Coordinates: 53 ° 33 ′ 36.8 ″ N , 9 ° 58 ′ 51.9 ″ E