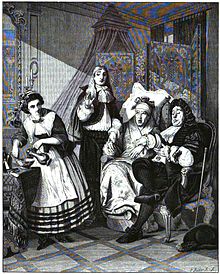

The conceited patient

| Data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | The conceited patient |

| Original title: | Le Malade imaginaire |

| Genus: | Ballet comedy |

| Original language: | French |

| Author: | Molière |

| Music: | Marc Antoine Charpentier |

| Publishing year: | 1673 |

| Premiere: | February 10, 1673 |

| Place of premiere: | Palais Royal, Paris |

| Place and time of the action: | Paris in the 17th century |

| people | |

|

|

The conceited sick (in the original Le Malade imaginaire , literally The conceited or supposedly sick , mostly performed in German under the erroneous title The conceited sick ) is one of Molière's most famous plays and at the same time his last work. The comedy in three acts premiered on February 10, 1673; the role of the eponymous hero was played by the poet himself. But at the fourth performance, on February 17, 1673, he suffered a hemorrhage ; he died, still in his costume, just a few hours later.

content

The piece is about the hypochondriac argan who only imagines he is sick. So he consults various doctors who are the only ones who relieve him of his imaginary illness and support him in it. He patiently obeyed all orders from his doctor, Monsieur Purgon, and carried them out precisely. This fact comes in handy for the doctor himself, and he prescribes unnecessary treatments for Mr. Argan against overpriced bills. Argan, on the other hand, wants his daughter Angelique to marry Thomas Diafoirus , a newly qualified medical doctor - for purely selfish motives . However, Angelique is in love with Cléante .

Together with Argan's housemaid Toinette , Béralde , the supposedly ill's brother , makes several attempts to cure Argan from his obsession with doctors. Finally, the two persuade him to pretend to be dead to find out if his wife and daughters really love him. Here Argan recognizes the true love of his daughter and the greed for money of his second wife, who is not Angelique's birth mother . In the end, Angelique is free to marry whomever she wants - on condition that her future husband is or will be a doctor. Instead of making Cléante a doctor, as he suggests, Béralde persuades the hypochondriac Argan to become a doctor himself. In addition, a mock ceremony with actors is immediately held, in which Argan , who considers the pretend ritual of admission to the medical profession to be serious, swears in Latin that he is worthy of wearing his medical cap.

Laughing at death as a central theme

An important theme in The Conceited Sick is "playing with death". Death appears again and again: Argan is afraid of dying, the lovers Angélique and Cléante no longer want to live if they cannot be united, Argan's youngest daughter uses the game with death as a ruse to avoid a beating, and Argan's second wife, Béline, is just waiting for Argan to die so that she can reap her inheritance. To top it all off, Argan plays dead to find out the true feelings of his wife and daughter. Despite this really serious subject, The Conceited Ill remains a real comedy. Laughing at death is achieved in several ways.

Laughing at Argan

For one thing, the audience laughs at the protagonist : Argan is obsessed: He claims to be sick, but no one apart from his doctors believes him. That's why he looks weird. If Argan really suffered from as serious an illness as he claims to be, one would feel sorry for him or share his fear of death. So it takes a certain emotional distance to the funny hero. Bergson speaks of a "anesthésie momentée du cœur" (Eng. "Temporary anesthesia of the heart"). If the viewer agrees to Argan's fate, it seems rather tragic: Argan is afraid of dying, he suffers. It is apparently difficult to determine by what, but that does not necessarily mean that he is not sick: There are many diseases that seem to have no physical cause and yet are no laughing matter. These aren't really reasons to laugh at him. But since the title of the piece suggests to the viewer that Argan is actually not ill, he can "switch off" his sympathy and laugh. Argan's illness is exposed as an obsession that determines all of his actions: For example, it drives him to decide to marry off his daughter to the young doctor Thomas Diafoirus, although his daughter obviously does not want him, because she wants to marry Cléante .

Anyone who has exposed Argan's illness as an obsession may laugh at him out of a certain feeling of superiority. The viewer knows more about Argan than he does about himself. “There is a comedy of naive naturalness [...]. Only under the condition of this naivety, i. H. the unconsciousness of the subject with regard to his external determination, it becomes really funny ”(Stierle, Text als Action, p. 61) Argan sees neither himself nor his actions as funny, because he believes in his fixed idea. So he's involuntarily weird and therefore seems more fun than an active joker. “So in the hero's passivity lies its dramatic and comical effect. He believes he is acting and is pushed by forces invisible to him. However, he who sees the hidden machinery of the world will laugh in superiority. ”(Müller, Theory of Comics, p. 60) He compares the comic hero with himself and comes to the conclusion that he would never commit this stupidity himself . Molière describes it as the task of comedy "to improve people through entertainment". Through distance and arrogance, the viewer succeeds in recognizing what he wants to avoid himself: "See the miser there on the stage, the boor, the conceited patient, dear viewer, you will not want to be like him [...]?" (Weinrich , Laughing is healthy, p. 405) Perhaps the viewer laughs who sees Argan's illness exposed as an obsession, but also because he knows that the tension that the character Argan carries within itself and thus also transmits will dissolve into nothing becomes. He lets himself be captivated by Argan's fear and laughs at the same time because he knows that nothing bad can happen, as Kant puts it: "Laughter is an effect of the sudden transformation of a tense expectation into nothing." (Kant, Critique of Judgment , P. 437)

Laugh at the medics

Another aspect that makes us laugh at death is the way in which the doctors are portrayed: The subject of medicine or the medical profession already appeared in the French theater of the Middle Ages and can be found both in pieces of the commedia dell'Arte as well as in the French theater of the 17th century. Molière picks up on the subject for the first time in Le médecin volant , a very early farce to which, however, no major importance is attached. In Dom Juan ou le Festin de Pierre (1665) it is sufficient for Sganarelle (a servant) to put on the doctor's robe in order to appear highly learned and thus to speak. Two important motifs emerge: the technical jargon ascribed to medical professionals and the motive that clothing already defines the medical professional. In the same year Molière wrote the “violent […] personal […] satire” (Grimm) L'amour médecin . A year later, the equally violent doctor satire Le Médecin malgré lui appears . In 1669, two doctors who had bought Monsieur de Pourceaugnac tried to persuade him of a "mélancolie hypocondriaque" in the play of the same name. In Le Malade imaginaire , Molière seems to have developed a certain gentleness towards doctors and medicine: Argan's doctor Monsieur Purgon is portrayed here as stupid because he is completely addicted to medicine and believes in it, but he does not act out of bad will or bad will out of pure greed for money.

So the medic is already an integral part of the comedies of that time. He seems strange because he is responsible for the body (for example, he examines urine). In doing so, he breaks a great taboo of the 17th century.

In addition, the medic is generally viewed as a con man. He always appears in his doctor's robe and speaks in a very specific technical jargon that tries to put himself above the others. However, he cannot achieve anything and only ever prescribes the same treatment methods and medications (enemas, bloodletting and diets). The physician sees himself as an authority, but cannot live up to this claim. (Not even his Latin is correct!)

Another point is the medical profession's belief in authority: They trust the ancient teachings and the medical faculty completely. They shut themselves off from everything new, as in The Imaginary Sick, for example, to the bloodstream . The physician acts in an externally determined manner and, due to his extreme dependence on the medical faculty, often appears unrealistic. This is particularly clear in Thomas Diafoirus' The Conceited Ill : He comes to the house of Argans to propose to Angélique (2nd act, scene 5). First he greets Argan himself with pompous words, then he turns to Angélique, whom he takes to be Béline, her stepmother, since it is proper to greet the bride's parents first, so the second person who is in his Put away to be the mother of the bride. When he finally has the belated Béline in front of him, he stutters and forgets the text he has memorized. The marriage proposal that he finally makes Angélique looks stilted, and the gift he offers her clearly shows how little he is and how much he is a doctor: he hands her his dissertation and an invitation to come along to the dissection of a woman.

Playing with death

Little Louison is responsible for making the audience laugh at death. Louison is Argan's 7 or 8 year old daughter. She uses death as a ruse: "Wait, I'm dead." (Act 2, Scene 8), but because of her childlike nature, this ruse becomes a game. We're used to laughing at childishness and games. There is an inherent lightness in both that assures us that nothing bad can happen. In this way a childlike attitude towards death is established (with the help of the figure of the child), which negates the reality of death, which the viewer is repeatedly made aware of by Argan's fear of death. Getting involved in Louison's game creates a feeling of immortality.

In the scene between Argan and Louison, Argan's fear of death is expressed again when he immediately pretends to be convinced that he killed his daughter with the rod, whereupon Louison consoles him: "I'm not quite dead". So Argan's reaction seems exaggerated and ridiculous. Louison is not afraid of death. You, the child, is a symbol for life, which forms a bright contrast to the ever-present symbols of death. Life in this scene has such power that Argan even forgets his illness: "I don't even have time to think about my illness".

Nevertheless, he does not lose his fear of death: When Toinette persuades Argan to pretend to be dead so that Béralde would be convinced of Béline's good intentions, he hesitates: "Isn't it dangerous to pretend to be dead?" Act, scene 11) Death is played here again. Louison imitated death without his being able to harm her, and now Argan is to take this risk too. This game with death is somewhat reminiscent of the comedy La Calandria by Bibbiena , in which Calandro is put in a box by his servant in order to come to a rendezvous. But Calandro fears dying in the box, whereupon his servant Fessenio explains to him that although one dies in such boxes, this is nothing other than falling asleep. So you have to practice it just like waking up. Religious beliefs about death certainly play a role here, such as the idea that one falls asleep in order to wake up again at the Last Judgment. These ideas can also be suspected behind Louison's above-mentioned appeasement. Playing with death, as it were, unrealizes it: “As the viewer isolates the comic fact and brings it to view as this, the moment of threat to the world of action that lies within him is perceived as accidental and eliminable. After laughing, the world is brought back into balance, the comical entanglement is negated by being dropped in laughter. "(Stierle: text as action)

expenditure

- Molière: The conceited patient. Comedy in 3 acts (original title: Le malade imaginaire , translated and afterword by Doris Distelmaier-Haas), Reclams Universal-Bibliothek 1177, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 978-3-15-001177-5

- Translated by Walter Widmer, Hamburger Reading Books, Issue 175, Hamburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-87291-174-2 .

literature

- Karlheinz Stierle : text as action. Perspectives of a systematic literary study . UTB 423 / Fink, Munich 1975. ISBN 3-7705-1056-9

- Harald Weinrich : What does “Laughter is healthy” mean . In: Warning Preisendanz, Rainer Warning (Hrsg.): Das Komische . Fink, Munich 1976. pp. 402-409, ISBN 3-7705-1411-4 (= Poetics and Hermeneutics , Volume 7).

- Irene Pihlström: Le Médecin et la médecine dans le théâtre comique français du XVIIe sciècle . Uppsala 1991.

- Immanuel Kant : Critique of Judgment . In: the same: works . Volume 8.

- Gottfried Müller: Theory of the comedy. About the comic effect in theater and in film . Triltsch, Würzburg 1964.

- Johannes Hösle: Molière. His life, his work, his time . Piper, Munich / Zurich 1987. ISBN 3-492-02781-4 .

- Jürgen Grimm : Molière . Metzler, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-476-10212-2 .

- Henri Bergson : Le rire. Essai sur la signification du comique . In: Ders .: œuvres . Paris 1963, pp. 383-485.

- Frauke Frausing Vosshage: Molière: The conceited sick person. König's Explanations and Materials Volume 418, Bange , Hollfeld 2008, ISBN 978-3-8044-1798-4 .

Film adaptations

In 1952, Hans H. König filmed the play under the title The Imaginary Sick with Joe Stöckel , Oskar Sima , Inge Egger , Jupp Hussels and Lucie Englisch in the leading roles. In 1979, in Italy, directed by Tonino Cervi with Alberto Sordi in the lead role and with Laura Antonelli , Giuliana de Sio and Marina Vlady one another version under the title Il Malato Immaginario .

Web links

- The conceited sick person at Zeno.org ., German translation from 1945.

- The author and the piece at-klassiker-der-weltliteratur.de

- Molière de A à Z at toutmoliere.net (French)

Individual evidence

- ↑ First dedication (“Placet”) of Tartuffe to King Louis XIV.

- ^ The conceited sick man (1952). Internet Movie Database , accessed May 22, 2015 .

- ^ The imagined sick man (1979) at zweiausendeins.de