The Prague orgy

The Prague orgy. An epilogue (English original title: Epilogue: The Prague Orgy ) is a novel by the American writer Philip Roth , which was published in 1985 by the New York publisher Farrar, Straus and Giroux . According to the subtitle, it serves as an epilogue to the trilogy about the Jewish-American writer Nathan Zuckerman, which is based on the novels The Ghost Writer (1979, German: The Ghost Writer ), Zuckerman Unbound (1981, German: Zuckerman's Liberation ) and The Anatomy Lesson (1983 , German: The anatomy lesson ) exists. The German translation by Jörg Trobitius was published by Carl Hanser Verlag in 1986 .

content

In January 1976 the American writer Nathan Zuckerman met his colleague Zdenek Sisovsky, who had emigrated from Czechoslovakia , and his compatriot, the actress Eva Kalinova. Sisovsky fell out of favor due to a satire and has been banned from publishing since the crackdown on the Prague Spring . Eva, on the other hand, who was married to the state prize winner Petr Kalina, has been feeling the anti-Semitism of the communist rulers since a relationship with the Jewish public enemy Pavel Polak , in which even a young stage role as Anne Frank is declared as proof of her Zionism . Both leave their homeland as part of an exit permit for regime critics, but are artistically and personally uprooted in America.

Sisovsky tells Zuckerman about his father, a Jew who stood between cultures in the interwar period and wrote Yiddish literature that was never published. During the German occupation , Sisovsky's father died as a result of a quarrel between two Gestapo officers who shot each other's Jewish protégés. The stories he left behind are in the care of Sisovsky's wife Olga, who stayed behind in Prague and fell out with her husband. Sisovsky sees the only way to salvage and posthumously appreciate this literary treasure in the mediation of a famous American writer for whom Olga would do anything out of love.

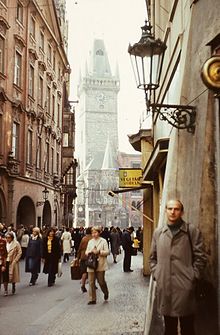

Almost a month later, Zuckerman is in Prague . The city, which is run down in all its tradition, and the dejected people awaken memories of the city of persecuted Jews that Zuckerman imagined in his youth. People live under ubiquitous surveillance and spying, artists and intellectuals are forced into menial jobs in order to keep leadership positions free for corrupt drunkards. But at an evening party in the house of the director Klenek, Zuckerman also experiences a desperate exuberance and permissive openness that the American only knows from his literary imagination. He meets the formerly celebrated theater director Bolotka, who despite all the harassment cannot bring himself to leave his hometown and his sixteen Prague friends. As a ghostwriter, he once wrote the spy minutes of his friend Blecha, who has since advanced to become a celebrated state writer.

In fact, Sisovsky's wife Olga falls in love with Zuckerman at the party and wants to marry him on the spot. On the following day she realizes bitterly that the American writer is only interested in the stories of her father-in-law. When she nevertheless hands him the manuscripts, this is not hidden from state surveillance. The police seized them while they were still in the hotel, and Zuckerman was forced to leave the country immediately. The Czechoslovak Minister of Culture, Novak, personally accompanies him on a surreal car ride, during which Zuckerman is reminded of Kafka's transformation . Novak reveals a cultural understanding that does not extend beyond Betty MacDonald , and contrasts the alienated artists Zuckerman has met with his father, who embodies the true Czech spirit by cheering every ruler in his country's checkered history.

During customs clearance at the airport, Zuckerman is relieved to have escaped the threat of repression, but at the same time he is depressed by the failure of his mission in less than 48 hours. After the loss of Sisovsky's father's manuscripts, another Jewish writer will not make a lasting impression on the world. And while Zuckerman temporarily hoped to shed his own story in Prague, the city of stories, he realizes that this is all that remains for him and that he will never be able to escape it.

background

During his unhappy first marriage in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Roth discovered Franz Kafka's literature , which reflected his life and which had a formative influence on his own works. It was also the search for traces of his role model that led Roth to visit Prague for the first time in 1972. What he found was a city that reminded him of the Newark of his youth, “a shabby, impoverished provincial town under the cloud of war”, but also a “mix of irony, intelligence, melancholy, resignation, self-satire, patience and Hope ”, in which he felt as if he was in the“ Jewish national homeland ”of his childhood fantasies. Roth met writers such as Ludvík Vaculík , Milan Kundera , Ivan Klíma and Václav Havel , whose living conditions were completely different from his own and whose predicaments he began to be interested in, as he was always drawn to individual or social constraints. As a result, Roth visited Prague every spring until he was denied his entry visa in 1977. As editor of the Writers from the Other Europe series at Penguin Books , he remained an important facilitator of Eastern European literature in the United States, and in 1990, a few months after the Velvet Revolution , he returned to Prague.

In a 1983 New York Times Book Review comment , Roth named his trips to Prague as the starting point for the Zuckerman trilogy. The contrast between life as a writer in America, “where everything is possible but nothing matters”, and communist Czechoslovakia, “where nothing is possible but everything matters,” has its view of the life of a Jewish- American writers like Nathan Zuckerman and had become the starting point for the following three Zuckerman novels. While Roth relegated his Prague experiences to his unwritten memories in 1983 because they might be too wild and rich in contrast for a book, he later translated them into an epilogue that he added to the Zuckerman trilogy, which had actually been completed. With this epilogue, which, like The Ghost Writer , the first volume of the trilogy, is written in the first person (in notes from Zuckerman's notebooks), the narrative time of the trilogy spans 20 years. According to Roth, the trilogy begins “with a pilgrimage to the patron saint of seriousness, to EI Lonoff, and it ends [...] at the Shrine of Suffering, in Kafka's occupied Prague”.

The absurd encounter with the Czechoslovak culture minister, Novak, who despises Kafka but praises Betty MacDonald and her “masterpiece” The Egg and I , has a real core to it. In fact, the humorous book about the experiences of a young woman on a chicken farm, popular in the United States at the end of the 1940s but later forgotten, developed into a long seller in the CSSR and is still extremely popular in the Czech Republic in the 21st century. Stanislav Kolář believes it is likely that Roth learned of the book's popularity there during his visits to Czechoslovakia. In the novel, the writer Zuckerman experiences that in a country where Betty MacDonald is revered as a star, he doesn't even have an extra role. The reason for the expulsion, the accusation that Zuckerman was a Zionist agent, points to Roth's later novel Operation Shylock , in which the narrator actually works for the Mossad .

reception

For Harold Bloom , Philip Roth outdid himself in the Prague orgy . In addition to the surrealism Kafka Bloom discovered in the novel, the evocation of a paranoia that Thomas Pynchon's Crying of Lot 49 equals, and a quest to rescue the hero, the manuscripts of a Yiddish writer through seduction of her guardian, a parody of Henry James's Aspern Papers is . The final scene, in which Zuckerman has to endure the moral sermon of the Czech culture minister, is more subtle, sadder and funnier than anything Roth has written before. Michiko Kakutani sees the epilogue as more ambitious than the earlier volumes of the Zuckerman trilogy and "free of their shrillness and self-pity". By contrasting Zuckerman's dilemma with that of his fellow writers in Prague, it develops a ridiculous comedy. Zuckerman envies the moral and historical significance of literature during the dictatorship, but in the end he has to realize that he can never make the stories of his colleagues in Prague his own.

Volker Hage reads Roth's epilogue as a “shrill accent” on the calmly told trilogy. The sexual revolution in Zuckerman's scandalous novel, a "revolt against the fathers", loses its effect in Prague. There the liberated sexuality only serves "to comfort the oppressed". The novel is "undoubtedly one of the most bizarre and funniest final cadences in modern literature". Maxim Biller finds in the book "none of the defiance, the cheek, the blasphemies of Portnoy-Carnovsky-Roth-Zuckerman", but rather "humility and submission". Zuckerman, who always rebelled against the “Jewish legacy of suffering”, was himself a victim of hostility towards Jews for the first time in Prague. It is precisely in the resemblance of the Prague intellectuals, who approach their oppression with just as sharp a sense of humor as the Jews, that Zuckerman understands "the uniqueness of Jewish persecution, the uniqueness of anti-Semitism in its irrationality, in its malevolent vitality, in its geographical and historical globality." Philip Roth "found his way back to his old literary powers with the Zuckerman trilogy".

expenditure

- Philip Roth: Epilogue: The Prague Orgy . In: Zuckerman Bound . Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York 1985, ISBN 0-374-51899-8 .

- Philip Roth: The Prague orgy. An epilogue . From the American by Jörg Trobitius. Hanser, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-446-14678-4 .

- Philip Roth: The Prague orgy. An epilogue . From the American by Jörg Trobitius. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1991, ISBN 3-499-12312-6 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Thomas David: Philip Roth. Rowohlt's monographs . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2013, ISBN 978-3-499-50578-2 , pp. 94-103, citations p. 98.

- ↑ Philip Roth: The Book that I'm Writing . In: The New York Times Book Review, June 12, 1983.

- ↑ a b Volker Hage: The last of the old-fashioned sons . In: Die Zeit of December 5, 1986.

- ↑ Thomas David: Philip Roth. Rowohlt's monographs . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2013, ISBN 978-3-499-50578-2 , p. 108.

- ^ Stanislav Kolář: Philip Roth and Czechoslovakia . In: Litteraria Pragensia , vol. 25 (2015), No. 49, pp. 6–21, here: p. 14.

- ↑ Mark Shechner: Up Society's Ass, Copper. Rereading Philip Roth . University of Wisconsin Press, Madison 2003, ISBN 0-299-19350-0 , pp. 106-107.

- ↑ Harold Bloom: His Long Ordeal by Laughter . In: The New York Times, May 19, 1985.

- ↑ " The Prague Orgy is free of the shrillness and self-pity that mar earlier sections of this volume". Quoted from: Michiko Kakutani: Books of the Times: Zuckerman Bound . In: The New York Times, May 15, 1985.

- ↑ Maxim Biller: The time of the monsters is over . In: Der Spiegel . No. 6 , 1987, pp. 192-198 ( online ).