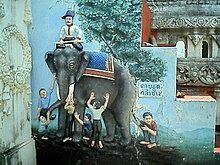

The blind men and the elephant

In the parable The Blind Men and the Elephant , a group of blind men - or men in total darkness - examine an elephant to understand what the animal is. Each examines a different part of the body (but each only a part), such as the flank or a tusk. Then they compare their experiences with one another and find that each individual experience leads to their own completely different conclusion.

In the parable, blindness (or being in the dark ) stands for not being able to see clearly ; the elephant represents a reality (or a truth ).

The story should show that reality can be understood very differently, depending on which perspective one has or chooses. This suggests that an apparently absolute truth can also be "relatively absolute" or "relatively true", i.e., only "relatively absolute" or "relatively true", through actual knowledge of only incomplete truths. H. individually and subjectively , can be understood.

Origin and variants

The parable appears to have originated in South Asia , but its original source is still under discussion. It has been attributed to Sufism , Jainism , Buddhism , or Hinduism and was used in all of these beliefs. Even Buddha used the example of rows of blind men to the blind following of a leader or an old text which has been passed down from generation to generation to illustrate. The version best known in the West (and mainly in the English-speaking world) is the poem by John Godfrey Saxe , from the 19th century. All versions of the parable are similar and only different

- in the number of men examining the elephant.

- in the way the elephant's body parts are described.

- in the way - in relation to violence - the discussion that follows.

- how (or whether) the conflict between the men with their individual perspectives is resolved.

Jainism

One version of the parable tells that six blind men were asked to determine what an elephant looked like by examining a different part of the animal's body, each individually.

The blind man who feels the leg says that an elephant is like a pillar; the one who feels the tail to make an elephant feel like a rope; the one who feels the trunk, that an elephant resembles a branch; he who feels the ear that an elephant should be like a hand fan; the one who feels the stomach that an elephant looks like a wall; the one who feels the tusk that an elephant must be like a solid pipe.

A sage tells them

- You are all right. The reason why each of you explains it differently is that each of you has touched a different part of the elephant's body. Because the truth is, an elephant has all of the qualities you mentioned.

The explanation resolves the conflict and is used to illustrate the principle of harmonious coexistence between people of different belief systems and to show that the truth can be explained in different ways. It is often mentioned in Jainism that there are seven versions of the truth. This is called Syādvāda , Anekāntavāda , or the theory of multiple predictions .

Buddhism

A Buddhist version is told in Udāna VI 4-6, “Parable of the blind men and the elephant”. Buddha tells the parable of a Raja who gathered men born blind to examine an elephant.

- "After the blind men felt the elephant, the Raja went to each of them and said, 'You have seen an elephant, you blind men?' - "So it is, your Majesty. We saw an elephant." - 'Now tell me, you blind people: What is an elephant?'

They assured him that the elephant was like a pot (head), a soft basket (ear), a ploughshare (tusk), a plow (trunk), a granary (body), a pillar (leg), a mortar (back) ), a pestle (tail), or a brush (tail tip).

The men begin to fight, which amuses the Raja and the Buddha explains to the monks:

"That is what they, the pilgrims or clergymen, hang on; they argue, argue, as people who only see parts of it."

Islam - Sufism

The Sufi poet Sana'i of Ghazna († 1131) used the story in his book Ḥadīqat al-ḥaqīqat ("The Garden of Truth") as a parable for people's inability to fully understand God.

Jalal ad-Din ar-Rumi was a Persian poet, lawyer, theologian, and Sufism teacher in the 13th century. Rumi, in his version of the parable "The Elephant in the Darkness" in the poem form Masnawī, attributed this story to an Indian origin. In his version, some Indians exhibit an elephant in a darkened room.

In the translation by AJ Arberry , some men feel the elephant in the dark. Depending on where you feel it, they believe the elephant is a water hose (trunk), a fan (ear), a column (leg), and a throne (back). Rumi uses this parable as an example of the limits of individual perception.

- The perceiving eye is just like the palm of the hand. The hand is unable to grasp the animal in its entirety.

Rumi does not present a solution to the conflict in his version, but notes:

- The view of the sea is one thing and the spray is another. Forget the spray and just look at the sea. Spray from the sea during the day and night: wonderful! You look at the spray, but not the sea ... our eyes are darkened and yet we are in clear water.

John Godfrey Saxe

One of the most famous versions of the 19th century was the poem The Blind Men and the Elephant by John Godfrey Saxe (1816-1887).

The poem begins with

- It was six men of Indostan to learning much inclined,

- Who went to see the Elephant (though all of them were blind),

- That each by observation might satisfy his mind

In free translation:

- It was once six men (Hindu aunts), inclined to learn a lot.

- They went to see an elephant (although they were all blind)

- that everyone through his contemplation can 'acquire and preserve knowledge.

The blind come to the conclusion that the elephant is like a wall, a snake, a spear, a tree, a fan or a rope, depending on where they have felt it. They get caught up in a heated, non-violent debate, but Saxe's version doesn't resolve the conflict.

- Moral:

- So often in theologic wars, the disputants, I ween,

- Rail on in utter ignorance, of what each other mean,

- And prate about an Elephant not one of them has seen!

In free translation:

- Moral of the story ':

- Frequently in the war of theologians to combat luminaries .

- What one has recognized as truth, the other revile as a lie,

- And babble about an elephant nobody has ever seen!

relevance

This parable is often applied (as described above) to theological arguments and religious incompatibilities. But it can be applied equally to social or scientific perspectives: even if you see an elephant in its entirety, if you have measured it, examined its organs and skeleton , if you have sequenced and compared its DNA and if you know its metabolism , this realization will always only remain a partial reality , because (a) you then do not know, for example, what peculiarities of his social behavior, how he communicates and how he perceives his environment and himself, etc. s. w. or (b) even if one could capture all conceivable data and facts about an elephant, no single person would be able to fully grasp the true overall picture of an elephant - based on his intellectual capacity.

Quantum physics in particular gives this ancient story a modern dimension: the wave-particle dualism shows how an elementary particle - depending on the experimental setup - can be described both as a particle and as a wave.

various

A processing as a picture book for children with the title The Blind Men and the Elephant (not published in Germany) was carried out by Karen Backstein and illustrated by Annie Mitra. Especially one picture is worth mentioning in which body parts of the elephant consist of a wall, a snake, a spear, a tree, a fan and a rope. In the children's book Die Elefantenwahrheit by Martin Baltscheit , published in 2006, there is a similar picture with a fire hose, carpets, tree trunks, a mountain and a toilet brush.

From the illustrator and children's book author Ed (Tse-chun) Young there is a picture book ( Seven Blind Mice , English Seven blind mice ) with the same subject, in which the men are replaced by seven mice in rainbow colors, discover the one after the elephant.

Natalie Merchant set John Godfrey Saxe's poem to music. It appeared on their 2010 album Leave Your Sleep .

The American cartoonist Sam Gross has published a book that shows the blind men and the elephant on the cover, but here with the variant that one of the men feels a pile of elephant solution. The title of the book: An Elephant is Soft and Mushy (An elephant is soft and mushy; not published in Germany).

There is a joke in which three blind elephants argue about what a man looks like. The first feels the man with his foot and says that a man is soft and flat. The other two elephants feel the man in the same way ... and agree.

There is also a pogo comic by Walt Kelly related to this parable: Pogo Opossum states that "each of the blind men was partially right," to which Churchy Lafemme the tortoise replies, "Yes, but for the most part they were all wrong."

literature

- Udo Tworuschka : About the moon, the many paths, the chameleon and precious stone and the elephant. Religious encounters in interreligious images. In: Wolfgang Dahmen, Petra Himstedt-Vaid, Gerhard Ressel (eds.): Border crossing. Traditions and Identities in Southeast Europe. Festschrift for Gabrielle Schubert. (Balkanological publications, Eastern European Institute of the Free University of Berlin, edited by Nobert Reiter, Holm Sundhausen, vol. 45) Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2008, pp. 663–678, ISBN 978-3-447-05792-9

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Elephant and the Blind Men . In: Jain Stories . JainWorld.com. Archived from the original on January 23, 2009. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved August 29, 2006.

- ↑ a b Fritz Schäfer: MEMBERS OF DIFFERENT SCHOOLS (1) . Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel : Sufism: An introduction to Islamic mysticism , Verlag CH Beck; ISBN 978-3-406-46028-9 - pp. 52/53

- ↑ a b A. J. Arberry: 71-The Elephant in the dark, on the reconciliation of contrarieties . In: Rumi - Tales from Masnavi . May 9, 2004. Retrieved August 29, 2006.

- ↑ a b cs.rice.edu: The Blind Men and the Elephant ( Memento of November 6, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) by John Godfrey Saxe

- ↑ ISBN 0-590-45813-2

- ↑ Martin Baltscheit , Christoph Mett: the elephant truth. Children's book publisher Wolff, Frankfurt / Main 2006, ISBN 978-3-938766-31-6

- ^ Andrzej Lukowski: Review of Natalie Merchant - Leave Your Sleep. In: BBC. April 12, 2010, accessed June 10, 2018 .

- ^ ISBN 0-396-07823-0

Web links

- Palikanon, Khuddaka Nikaya, Udana VI 4-6, translated by Karl Seidenstücker (1920)

- Palikanon, Khuddaka Nikaya, Udana VI 4-6, translated by Fritz Schäfer (1998)

- Palikanon, Khuddaka Nikaya, Udana (Pali) 54-56

- Story of the Blind Men and the Elephant (PDF; 78 kB) from www.spiritual-education.org (PDF file; 76 kB)

- All of Saxe's Poems including original printing of The Blindman and the Elephant (Engl.) Without copyright and with text search function.

- Buddhist Version as found in Jainism and Buddhism. Udana hosted by the University of Princeton

- Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi's version as translated by AJ Arberry

- Jainist version hosted by Jainworld

- John Godfrey Saxe's version hosted at Rice University ( Memento of November 6, 2007 in the Internet Archive )