Direct democracy in the canton of Basel-Landschaft

The direct democracy in the canton of Basel-Country formed in the 19th century with the expansion of people's rights to state and municipal level and the concretization of popular sovereignty .

The canton of Basel-Landschaft introduced the people's veto in 1832 as the second canton (St. Gallen 1831, Lucerne 1841) . Although the design of the veto differed from that in St. Gallen, it had a major impact on the development of direct democracy in Switzerland during the regeneration . With the veto and especially with the obligatory referendum (1863), he actually played a pioneering role. No other canton had such a variety of direct democratic rights.

The Revolution of 1798 and the Certificate of Equality

The southern part of the Principality of Basel was occupied by the French at the end of 1797 . On January 15, 1798 the committees of the landscape issued an appeal based on modern natural law : Citizens! You know that the rural people demand their natural freedom, a right that God and nature have given every human being .

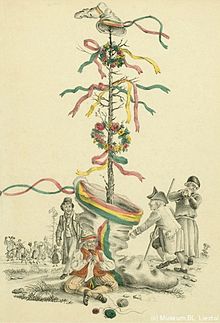

The Helvetic Revolution broke out on January 17, 1798 and the first tree of freedom in Switzerland was erected in Liestal .

The Basel city authorities (mayor, small and large councilors of the federal free state of Basel ) hastened to adopt and granted the so-called equality certificate , in which the Liestal 4-point demands of January 13, 1798 were adopted, at the large council meeting on January 20, 1798 thus all communities in the landscape full freedom and equality rights. On the same day, a freedom tree was erected on Basel's Münsterplatz .

The four requirements included in the certificate of equality were:

“ 1. That you are determined to stay Swiss. (Editor's note: "They" mean all communities in the Basel region.)

2. That they want freedom, equality, the sacred, non-statute-barred rights of people, and a constitution, for which representatives from the people are elected.

3. Close union of the city citizens with the country citizens, as belonging to one body, who have to enjoy equal rights and freedom, and

4. Immediately covet a popular assembly, including by city and country, according to rules to be determined, e.g. B. one of fifty citizens would be elected who could temporarily attend the future laws to be determined "

The first uprising as a regeneration revolution

The failure of the Helvetic Republic after 1798 brought the restoration of pre-revolutionary conditions from 1815 onwards . Although the deed of equality stated that the old relationships between town and country should never be restored, only a few years passed before the aristocratic city government gradually withdrew the rights granted by the deed.

When dissatisfaction with this situation grew in the population, Stephan Gutzwiller (1802-1875, lawyer and member of the Grand Council in Basel) wrote a petition for a new constitution to the city superiors. It was decided by 40 country citizens who met secretly in Bad Bubendorf and presented to the mayor with 750 signatures. In the petition, Gutzwiller referred to the certificate of equality , a copy of which was enclosed. The patriotic revolution of 1798 in Baselland, as in other cantons, became a central point of reference for the revolutions from 1830 onwards.

In the petition it was clearly indicated that they were ready to renew the bond with the city, but not at any cost:

“ In this abolition of equality and the unlawful way in which it has happened, we see the complete destruction of the most sacred rights assured to us by nature, by documents, and by the most solemn oaths sworn to God; we see in it the dissolution of the bond which formerly united town and country into one body; we finally see in it the germ of the dichotomy between city and landscape, which stirs with every external and internal cause and sooner or later our common fatherland would have to lead towards ruin "

The petition of Gutzwiller and his fellow campaigners did not go beyond the "Equality Certificate" of 1798, as this already included all content relevant to democracy. They argued in line with the document that, due to human dignity, all communities in the landscape should be granted happy freedom and equality for everyone. With the terms human dignity and communities , they tied in with the modern natural law according to Samuel von Pufendorf and the cooperative constitution of all communities, two important building blocks for democratization in Switzerland.

The common constitution of 1831

In response to revolutionary pressure, the Grand Council tackled the constitutional revision, which had already been rudimentarily discussed since 1829. However, the proposed constitutional draft did not bring the political circles around Gutzwiller the required equality with the city, since the representation of the landscape twice as large in terms of population in the Grand Council would still not have been representative.

In order to emphasize their demand, the landscape organized a "Landsgemeinde" (Landsgemeinde) in Liestal on January 4, 1831, with 2,000 to 3,000 people, based on the direct democratic model of the Swiss Landsgemeindekantons and the so-called People's Days in other cantons, and demanded representation in the Grand Council the population, the equality of all political and civil rights, a constitutional council elected by the people and a referendum on the revised constitution.

With the election of a provisional government on January 6th in Liestal, the first revolutionary act of the landscape followed. The municipal government in Basel responded to the uproar with the military occupation of Binningen , Allschwil and Liestal. The provisional government fled to Aarau .

On February 12, 1831, the Grand Council passed the revised constitution with the provisions on the direct election of the Grand Council, the census, the prerogatives of the capital, freedom of employment and the stipulation that a majority of town and country are necessary for the adoption of the constitution. This moderately liberal constitution was adopted by the majority of town and country citizens on February 28, 1831.

The second uprising and the separation of the Basel cantons

When a few months later the provisional government issued a daily order that released the countryside from obedience to the city government, the city government again deployed troops against Liestal. The Tagsatzung reacted to this second uprising in the countryside by occupying the Basel countryside by the federal military and calling on the city to accommodate the countryside. In the vote ordered by the city authorities on whether the landscape should remain with the city in 1831, a majority of the landscape voted against separation from the city, with strong abstentions.

Despite this democratic decision, the Grand Council decided to take action against the opposing municipalities and to withdraw public administration from them if they did not later commit to the canton of Basel by majority decision.

As a result, on March 17, 1832, a people's assembly in Liestal declared the 46 “punished” municipalities to be sovereign, thus laying the foundation stone for the new canton of Basel-Landschaft . The decision was based on the definition of “popular sovereignty” in Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Contrat social of 1762.

The introduction of the veto with the first constitution of 1832

The constitutional council elected by the landscape began to work out a constitution for Baselland and called on the population to submit proposals by means of petitions. The proposal for a single central rural community, which should have handled the legislative business, was rejected in the Constitutional Council because it was feared that the city could influence them for a reconnection, which would result in the loss of independence. Further proposals concerned the concretization of popular sovereignty, in particular by means of the veto, the right of citizens to accept or reject laws. Several petitioners referred to the example of the St. Gallen veto.

On the basis of the submissions, the commission established the following principle for popular sovereignty: "If the concept of popular sovereignty is to apply in its original clarity, the people must also be considered the highest authority in the state."

The liberals, like Gutzwiller and his supporters, wanted to stick to the representative system , saw the veto as dangerous and did not want to give the people legislative power. The other half of the Constitutional Council, the radicals, advocated more direct democracy.

At the decisive meeting of the Constitutional Council on April 27, 1832, a majority was in favor of the veto. The Constitutional Council had recognized - as it had done a year earlier in the canton of St. Gallen - that a law could meet with popular resistance even after the final vote in the district administrator. The principle of popular sovereignty required a democratic adaptation of the representation system with far-reaching consequences for political culture. The veto was designed differently than in St. Gallen, but was also subject to high hurdles (quorum of two thirds of the sovereign people). The constitution, which, in addition to the legal veto, contained the separation of powers and universal suffrage for men over 20 years of age, was clearly adopted by the voting population on May 4, 1832.

This declaration of sovereignty escalated the conflict with the city. However, the new canton of Baselland was able to maintain its independence after bloody clashes with urban troops. On August 16, 1833, the federal assembly sealed the total separation, subject to voluntary reunification.

The veto practice between "order" and "movement"

The veto hurdles for the veto were lowered in 1838 with the partially revised constitution. Instead of the rigidity period for constitutional amendments of six years, the absolute majority of those entitled to vote at open community meetings was now sufficient. The veto practice showed that the term legislation was not yet clearly formulated in the constitution and veto movements were also directed against ordinances. Twelve years later, the hurdles were further reduced, in which the scope of the veto was expanded and the objection period extended.

In the new canton there were no actual parties, but two political movements. The "order movement" under Stephan Gutzwiller advocated the principle of representation. After the founding of the canton, it tried to stabilize the revolution and help a certain order to break through. The "movement people" around Emil Remigius Frey , member of the provisional government and constitutional council, advocated broader popular rights and the veto, which was finally enshrined in the constitution , based on Jacobin - early socialist convictions. Newly founded newspapers and the freedom of the press achieved in Helvetic Republic made it possible to spread their political concerns to the public. Frey became editor of the new radical newspaper Volksblatt aus Baselland (1861) (1865 Basellandschaftliches Volksblatt). Stephan Gutzwiller was a regular employee of the Basellandschaftliche Zeitung .

Despite all the hurdles, the right of veto was implemented most consistently in the canton of Baselland. The process did not consist of a veto request and a veto vote (as in the cantons of St. Gallen and the canton of Lucerne), but consisted of the opponents' declarations of objection. It was both a veto initiative and a veto vote.

Up to 1862 there were 14 veto movements out of around 200 decrees , only four of which were rejected by active citizenship. For example, the veto against the discriminatory Jewish law could not prevail.

The introduction of the mandatory referendum with the 1863 Constitution

A popular movement around Christoph Rolle (1806–1870) wanted to improve the direct democratic system with a constitutional revision in 1861, in which the laborious veto process was to be replaced and in future all laws in the sense of a referendum were to be submitted to the voting population for acceptance or rejection. He turned against the ruling liberals, but found support from Emil Remigius Frey . In the signature collection launched by Rolle, a majority of those entitled to vote were in favor of a constitutional revision.

In the revised constitution of 1863, the veto was replaced by the mandatory referendum . At the same time, the constitutional and legislative initiative , the popular election of the government and the highest officials as well as the right of the people to recall the district administrator were introduced. This gave the population of the canton of Baselland a control over the executive (government) and legislature (district administrator) like in no other canton in Switzerland.

The current constitution dates from May 17, 1984.

literature

- Peter Ochs : History of the city and landscape of Basel . Volume 8, Schweighauser'sche Buchhandlung, Basel 1822

- Clear presentation of the proceedings of the Swiss Confederation observed against the state of Basel, extracted from the official meetings of the Diet and the council minutes of the Canton of Basel . Schweighauser'sche Buchhandlung, Basel 1833

- Johann Jacob Hottinger : Lectures on the history of the fall of the Swiss Confederation of the thirteen places and transformation of the same into a Helvetic Republic . Verlag S. Höhr and Meyer and Zeller, Zurich 1844

- Fritz Klaus: Basel landscape in historical documents. Part 1: The founding period 1798–1848, sources and research on the history and regional studies of the canton of Baselland . Volume 20, Liestal 1982

- Baselland 150 years ago, turning point and new beginnings: nine articles with a chronology of the Basel turmoil and the federal regeneration period 1830-1833 . Anniversary publisher, 1983

- The Basel landscape in the Helvetic Republic (1798-1803): on the material causes of revolution and counterrevolution . Publishing house of the Canton of Basel-Landschaft, 1991

- Rolf Graber (Ed.): Democratization processes in Switzerland in the late 18th and 19th centuries . Research colloquium as part of the research project “The democratic movement in Switzerland from 1770 to 1870”. An annotated selection of sources. Supported by the FWF / Austrian Science Fund. Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Vienna, 2008. 93 p. Series of publications by the International Research Center “Democratic Movements in Central Europe 1770-1850”. Vol. 40 Edited by Helmut Reinalter, ISBN 978-3-631-56525-4

- René Roca, Andreas Auer (ed.): Paths to direct democracy in the Swiss cantons . Writings on Democracy Research, Volume 3. Center for Democracy Aarau and Verlag Schulthess AG, Zurich - Basel - Geneva, 2011. ISBN 978-3-7255-6463-7 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Peter Ochs: History of the city and landscape of Basel . Volume 8. Schweighauser'sche Buchhandlung, Basel 1822, page 292

- ^ Fritz Klaus: Basellandschaft in historical documents. Part 1: The founding period 1798–1848, sources and research on the history and regional studies of the canton of Baselland . Volume 20, Liestal 1982, page 40

- ^ Johann Jacob Hottinger: Lectures on the history of the fall of the Swiss Confederation of the Thirteen Places and the transformation of the same into a Helvetian Republic , Verlag S. Höhr and Meyer and Zeller, Zurich 1844, page 330