Railway accident on the Firth of Tay Bridge

The railway accident on the Firth of Tay Bridge was caused by the collapse under a train from Edinburgh to Dundee on December 28, 1879. 75 people are believed to have died.

Starting position

The first Firth of Tay bridge was a three thousand meter long railway bridge over the Firth of Tay , which the engineer Thomas Bouch had constructed. The single-track bridge formed a block section of the railway line . Only the train whose engine driver was in possession of the "token" , a staff that he had to return after driving on the bridge, was allowed to drive on the bridge. Since there was only one such staff, it was ensured that there was only one train on the bridge at a time.

An express train ("Mail") of the North British Railway left Edinburgh Waverley Station for Dundee at 16:15 . He drove six passenger cars that were pulled by a 2-B express locomotive with a tender . The engine driver took the token at the block south of the bridge. The block attendant telegraphed the train passage to his colleague on the north side at 7:14 p.m. Arrival in Dundee was scheduled for 7:20 p.m.

There was a storm on the Firth of Tay that evening , which peaked around 7 p.m. The wind force was estimated at 10 to 11 on the Beaufort scale. A too heavy locomotive is said to have been in use on the bridge that day.

the accident

The express train from Edinburgh drove on December 28, 1879 in the dark on the middle part of the Firth-of-Tay-Bridge at around 7:17 p.m. when it gave way and fell with the train into the Firth of Tay. The bridge had collapsed under the weight of the train, the wind load of the hurricane and the excessive dynamic forces of the train under these circumstances. The ultimate cause was the poor construction and execution of the bridge.

Railroad worker and eyewitness John Watt, who was in the block post at the south end of the bridge at the time, chased the light of the train and watched it fall into the water. He said to the employee at the block: "Either the porters or the train fell down". The block attendant then found that all eight telegraph lines to the block location on the north side were interrupted. Since all the lines were integrated into the bridge structure, this was proof that the bridge was interrupted.

The accident was also observed on the north side of the bridge: “It was like a meteoric outbreak of wild sparks, thrown into the darkness by the locomotive. The ray of fire could be seen in a long trail, until it was extinguished below in the stormy sea. Then there was complete darkness. ”The station master of Dundee and the chief of the locomotive service there walked down the bridge in the dark to investigate the cause. The storm was still so strong that at times they only got on all fours. After about a kilometer they were left with nothing. The entire middle section of the bridge over a length of almost 1000 m, including the train passing through it, fell into the Firth of Tay. When the train was recovered, it was found that the locomotive's regulator was still open and the controls were in the forward position and there were no signs of an attempt to brake, so at least the locomotive staff apparently had no signs of the accident.

consequences

Direct consequences

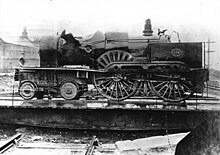

There were no survivors. 72 passengers and 3 railway employees who were traveling in the train were killed, including the son-in-law of the designer of the bridge. The exact number of victims could only be determined indirectly through the number of tickets sold . Only 46 bodies were recovered, the others were washed into the North Sea . The police were later able to identify 60 victims on the basis of the missing persons reports, so that ultimately 12 tickets sold could not be assigned. That is why the exact number of victims is still controversial to this day. Only two days after the storm had subsided, parts of the train could be located in the muddy water of the Firth of Tay. The locomotive that crashed into the water was later recovered from the fjord, repaired and was in use until 1919. She was nicknamed "The Diver" ("The Diver").

Investigative commission

Henry C. Rothery (Maritime Accident Officer), Colonel William Yolland (Chief Inspector of the British Railways) and engineer William Henry Barlow (Chairman of the British Engineers' Association and specialist in bridge building) formed the official commission of inquiry set up by the British Parliament . They concluded their investigation in June 1880 with two separate reports. The one signed by Yolland and Barlow spoke out against a personal guilt of Thomas Bouch. Rothery, on the other hand, was of the opinion that Thomas Bouch should be held responsible in court. Both reports came to the unanimous conclusion that a whole series of construction errors, ignorance and sloppiness during the construction work and then poor maintenance had led to the collapse of the bridge. There were also management errors of the North British Railway . It was known even before the collapse that components had detached from the bridge when the train crossed.

As a result of the accident, the construction of the Firth-of-Forth bridge , also planned by Thomas Bouch, was stopped. Sir Thomas Bouch fell ill as a result of the events and died on October 30, 1880, just ten months after the accident. He did not live to see the civil lawsuit that had already been initiated. But he took the view that a derailment of the train had caused the bridge to collapse.

The causes of the spectacular major accident were repeatedly the subject of discussion and renewed investigation in the period that followed; the material failure was based on fatigue fracture and construction errors .

See also

Literary processing

- Theodor Fontane immortalized the catastrophe in January 1880 in the mythical ballad Die Brück 'am Tay .

-

Wikisource: Die Brück 'am Tay - Sources and full texts

- William McGonagall also wrote a poem The Tay Bridge Disaster in 1880 .

- Max Eyth dealt with the accident in his short story Die Brücke über die Ennobucht , published in 1899 .

literature

- Peter R. Lewis: Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay: Reinvestigating the Tay Bridge Disaster of 1879. Tempus 2004. ISBN 978-0-7524-3160-4

- Bernd Nebel: The collapse of the Tay Bridge (website).

- NN: Failed design triggers horrific Tay Bridge terror . In: The Scotsman v. February 21, 2006.

- Lionel Thomas Caswell Rolt : Red for Danger . Edition: London 1978. ISBN 0 330 25555 X , pp. 95-104.

- Henry C. Rothery: Report on the Court Inquiry and Report of Mr. Rothery upon the Circumstances Attending the Fall of a Portion of the Tay Bridge on December 28th, 1879 (PDF; 2.1 MB). London 1880. (Official investigation report to the British Parliament).

- Adrian Vaughan: The Tay Bridge in: Railway Blunders. Ian Allen Publishing, Hersham, Surrey, 2nd edition 2009, pp. 30ff. ISBN 978-0-7110-3169-2

- Reporting in the Deutsche Bauzeitung :

- Havestadt: The collapse of the Tay Bridge near Dundee. In: No. 3, January 10, 1880, pp. 15-17; and

the collapse of the Tay Bridge. In: No. 7 of January 24, 1880, pp. 34-36 ( digitized on opus4.kobv.de); -

To the Tay Bridge collapse. In: No. 12 of February 11, 1880, p. 63; and

Havestadt: The Tay Bridge near Dundee and its collapse on December 27, 1879. In: No. 13 of February 14, 1880, pp. 66-67 ( [1] ), No. 16 of February 25, 1880, pp. 83-84; No. 21 of March 13, 1880, pp. 111-114 ( [2] ); -

To the collapse of the Tay Bridge. In: No. 15 of February 21, 1880, p. 82 and

On the Collapse of the Tay Bridge. In: No. 22 of March 17, 1880, pp. 117-118 ( [3] ); - To the collapse of the Tay Bridge. In: No. 51 of June 26, 1880, pp. 270, 272 ( [4] ;

- To the Tay Bridge collapse. In: No. 57, July 17, 1880, pp. 308-310 ( [5] );

- To the Tay Bridge collapse. In: No. 68 of August 25, 1880, p. 368 ( [6] );

- Sir Thomas Bouch. † In: No. 89 of November 6, 1880, p. 482 ( [7] );

- Reconstruction of the Tay Bridge. and On our note on the death of Sir Thomas Bouch. In: No. 92 of November 17, 1880, p. 495 ( [8] ).

- Havestadt: The collapse of the Tay Bridge near Dundee. In: No. 3, January 10, 1880, pp. 15-17; and

Web links

- Historical photos of the first bridge, before and after the accident

Files: Firth of Tay Bridge - local collection of images and media files

Files: Firth of Tay Bridge - local collection of images and media files - Tom Martin: Tay Bridge Disaster Web pages. Retrieved December 23, 2008 (analysis of the accident).

Individual evidence

Coordinates: 56 ° 26 ′ 18.5 ″ N , 2 ° 59 ′ 18 ″ W.

- ↑ Bernd Nebel: The collapse of the Tay Bridge (website).

- ↑ a b c Failed design triggers horrific Tay Bridge terror. Article in The Scotsman Archives, February 21, 2006 , accessed February 24, 2013.

- ↑ Philipp Frank: Theodor Fontane und die Technik , p. 47

- ^ Rothery: Report .

- ↑ Quoted from: Bernd Nebel: The collapse of the Tay Bridge (website).

- ^ Rothery: Report, pp. 9-10.

- ^ Rothery: Report (see: Literature).

- ↑ Tom Martin: Tay Bridge Disaster (website).

- ↑ Theodor Fontane: The Brück' on Tay . In: Ders .: Gedichte I. 2nd edition 1995 (Big Brandenburger Edition), pp. 153–155.

- ^ William Topaz McGonagall: The Tay Bridge Disaster

- ↑ Max Eyth: The bridge over the Ennobucht in the Gutenberg-DE project