Physical examination

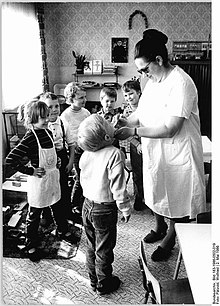

Physical examination (also clinical examination ) is a term often used in medicine for the examination of a patient with one's own senses and simple aids. The orienting or rough examination of the entire body or its organ systems is also known as a whole-body examination .

The physical examination is seen as an indispensable basis for diagnosis . The procedure is based on the so-called IPPAF scheme :

- I - inspection , viewing (general and local),

- P - palpation , palpation (skin, internal organs, body orifices),

- P - percussion , tapping (thorax, abdomen), and

- A - Auscultation , listening to body regions (thorax, abdomen, blood vessels), as well

- F - functional test (and measurements), at the end of the examination.

The physical exam is an important part of any medical student's clinical training. It is learned in so-called tapping courses (from tapping = percussion ) on voluntary patients and follows a fixed scheme in order to achieve completeness and systematics. The examination usually begins at the head and ends at the foot, and is based on the various organ systems.

At the beginning, in addition to the state of consciousness (awake? Oriented?), The so-called general and nutritional status is assessed. In unconscious patients, the degree of impaired consciousness caused by various stimuli (up to painful stimuli from pinching) is examined in a gross neurological manner . The color of the patient's skin reveals possible anemia , lung and heart diseases ( cyanosis ) or biliary obstruction ( jaundice ). Spots and other skin appearances can indicate infections or other illnesses, leg swelling ( edema ) indicates a weak heart or kidney problems. Arthritis or tremors of the hands can often be seen at first glance.

In the area of the head and neck, pupillary reactions and visual acuity are checked and the fundus is viewed (“mirrored”). The latter is z. B. Evidence of high blood pressure. The oral mucosa is viewed, the skull and cervical spine are tapped, the lymph nodes and thyroid are palpated, and the cervical vessels are monitored with a stethoscope . The sensory and motor function of the twelve cranial nerves can be checked in detail.

Other areas that are similarly amenable to examination are the spine , thorax including the heart , lungs and mammary glands ; the abdomen , the kidney region on both sides, the lymph node regions of the armpits and groin, the genitals , arms and legs (with the known reflex tests ) and the central nervous system.

The scope of the investigation depends on the question. Often one or two symptoms are found quickly, which influence the progress of the diagnosis. In rare cases where the symptoms are unclear, a detailed examination of all body regions may be necessary, which can take up to an hour. In practice, the examination is often shortened and carried out in a targeted manner. In order to save time and the patient from undressing, only the heart and lungs should never be examined through the neckline of the clothing (jokingly called the “checkout triangle”), except in an emergency.

Only when all of these examinations do not provide a clear clinical picture are devices of modern medicine (e.g. magnetic resonance tomography ) used to clarify the disease and its extent. Only a synopsis allows the doctor to put together a suitable therapy.

literature

- F. Konrad, A. Deller: Clinical examination and surveillance, bacteriological monitoring. In: J. Kilian, H. Benzer, FW Ahnefeld (ed.): Basic principles of ventilation. Springer, Berlin a. a. 1991, ISBN 3-540-53078-9 , 2nd unaltered edition, ibid 1994, ISBN 3-540-57904-4 , pp. 121-133; especially p. 122 f. ( Physical examination ).

- Rudolf Häring: Special surgical medical examination. In: Rudolf Häring, Hans Zilch (Hrsg.): Textbook surgery with revision course. (Berlin 1986) 2nd, revised edition. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1988, ISBN 3-11-011280-9 , pp. 1–6, here: pp. 3–5.

Individual evidence

- ^ Broglie-Schade-Gerhardt: Fee Handbook . Medical Tribune Publishing Company, July 1997.

- ↑ Martin U. Müller : Ada Health: App instead of a doctor. In: Der Spiegel . Retrieved February 2, 2019 .