Acquiring a bid

In German property law, the acquisition of bidding describes a special form of transfer within the meaning of Section 929 Sentence 1 BGB.

When acquiring command, third parties are involved in the transfer of property law who have no ownership relationship ( servant or brokerage relationship ) with a party. So-called instructors can be used on the buyer or seller side to assist in the transfer of the transfer of ownership. When acquiring command, it is assumed that an act of cooperation in the handover, which takes place on instruction, is equivalent to the act of cooperation of the instructing person.

Like security property, the acquisition of bid is not expressly regulated in German law. This also results in the criticism of this form of transmission, which, however, is opposed by a considerable need for traffic for this transmission route: To shorten cumbersome service and delivery routes, the acquisition of bidding via intermediaries or servants is indispensable.

Demarcation

The acquisition of bid is to be distinguished from the agency relationship and the property servants. It differs from the property servant insofar as there is no relationship of domination between the commanded person and the instructing party. The difference to both of the above-mentioned property rights relationships is that the evangelist has at most "isolated" direct possession and loses or acquires it during the act of transfer (although in multi-level supply chains it can also happen that the evangelist does not have possession of the thing at any point). It follows from this that the person ordered has no property relationship with the person on whose order he or she acquires or transfers possession of an object.

The different manifestations of the acquisition of bid

A distinction is made between different categories of secrecy according to the side on which the assistant is involved. Deliver a person at the behest of the transferor or accept a person at the behest of the acquirer. There are also cases where both of the aforementioned forms of bidding coincide.

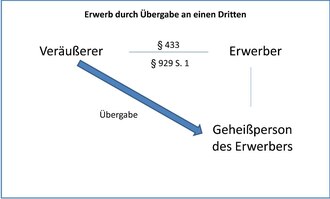

Acquisition by handing over to a third party

The direct possession is not granted to the purchaser himself, but the direct possession is granted by the transferor at the behest of the purchaser to a third party who is neither servant nor agent of the purchaser (the person in charge). The BGH recognized this constellation in the following case: The seller of a machine had delivered it to a lessee at the behest of his buyer, who was a leasing company . In this case, the handover to the lessee is equivalent to the handover to the lessee. The lessor thus becomes the owner by handing it over to the lessee, without ever having become the owner of the thing.

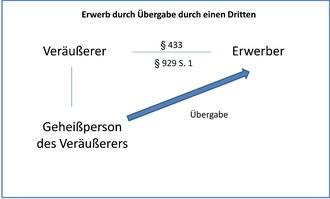

Acquisition by handover by a third party

In this constellation, the seller does not hand over the item to the buyer himself. At the behest of the alien, a third party acts who is neither his servant nor his agent (the person who is commanded). The following case offers a classic constellation: V sold and delivered a machine to G. Even before acceptance, G determines that the delivered machine does not have the contractually determined capacity and makes it available to V again immediately. V sells the machine to E and asks G to forward the machine to E. As the case shows, G did not become the owner, since with the acceptance he also rejected an agreement in rem. Nor does he have any ownership relationship with the seller, since he is neither a property broker nor a property servant of the V. Nevertheless, the transfer of the G to E results in an acquisition of property from V to E.

Combination of both cases

In addition, there are cases in which an auxiliary person participates in the act of transfer on both the purchaser's side and on the seller's side, who are not in any position regarding ownership of the purchaser or seller. These constellations are also summarized under the term double acquisition of bid.

A distinction is made between the two-stage, the two-stage or the multi-stage bidding.

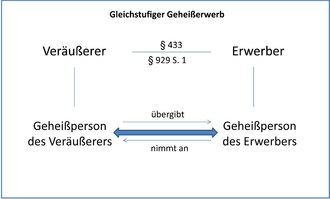

Equal bidding

As part of a unified acquisition process, beheaders appear on both sides. The thing is transferred by a person in charge of the transferor to another person in charge of the purchaser by transferring the direct possession.

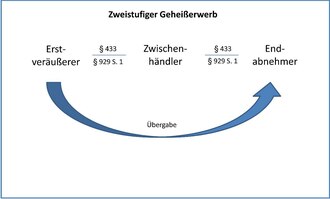

Two-stage bidding

The two-stage acquisition of bid is when the first seller delivers the sold goods directly to an end customer on the instructions of his contractual partner ( supply chain ). The first seller has no contractual relationship with the final buyer. This sequence is often found in a manufacturer's relationship with the distributor and their customers. This constellation is also known as drop shipping. Under the law of obligations, the middleman is on the one hand the buyer of the initial seller and on the other hand the seller of the final buyer. In terms of property law, the provision of direct property by the first seller to the final buyer on the instructions of the intermediary is also seen as a transfer of ownership to the intermediary. It is characteristic that both the first seller and the final buyer appear as the middleman in the acquisition process. On the one hand, the final purchaser is the agent of the intermediary for the acquisition of ownership from the first seller, because he accepts the thing at the behest of the intermediary. On the other hand, the first seller for the act of transfer between the middleman and the end customer is the person responsible for the transfer, because he hands over a thing at the behest of the middleman (transfer of ownership). The agreements of the real transactions can either be anticipated and declared parallel to the execution of the sales contract. It is also conceivable, however, that the middleman authorizes the first seller and the final buyer to declare the agreements , exempting them from the prohibition of Section 181 of the German Civil Code.

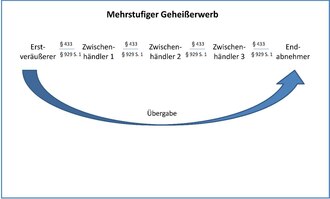

Multi-stage bidding

A more complex variant of drop shipping is the so-called multi-level bidding process. It differs from the two-stage bidding process only in that it has a larger number of intermediaries (at least two). This is the case, for example, when a manufacturer contracts with an intermediary. This middleman engages another middleman before the item is supposed to reach an end customer. Multi-stage combination cases of this kind lead to warring chains. In such a case, the BGH assumed that the property would "pass from the first seller one after the other, over all links of the chain to the last buyer". The delivery from the first seller to the last seller thus leads, according to the prevailing opinion, for a "logical second" to the acquisition of transitory property by the intermediaries involved.

criticism

However, there are also dissenting voices who either completely reject the acquisition of command or deny the acquisition of passage .

- The fundamental rejection of the acquisition of bid is justified by the fact that the instruction cases can be resolved through an intermediary relationship. This cannot be convincing for the simple reason that an intermediary relationship is always set up for a certain duration and is not only agreed for the moment of transfer of ownership

- In addition, there are voices that reject the pass-through acquisition and instead accept a direct acquisition by the last buyer from the first seller via Section 185 (2) sentence 1 alternative 2 BGB. Still others argue that the disposition of the secondary seller becomes effective through approval in accordance with Section 185 (2) BGB.

Admittedly, the approval of the acquisition of command, as it is assumed by the case law and prevailing opinion , represents a considerable weakening of the traditional principle, according to which the transfer of ownership requires not only agreement but also the provision of property. Against this criticism, however, it is convincingly argued that the publicity function of the traditional principle must in any case run empty in the case of mere passage acquisition in supply chains. In some cases, it is even stated that bidding is to be reconciled with the traditional principle insofar as the declared power to procure property is sufficient. For pragmatic reasons it should be noted that the acquisition of command is indispensable in a modern economic order. In supply chains, it would be uneconomical to first convey the item to one or even several intermediaries in order to fulfill the respective debt contracts before the last buyer in a supply chain receives the item. In view of the highly differentiated division of labor and the three-tier sales structure in numerous industries, the practical relevance of bidding can hardly be underestimated. In addition, §§ 930, 931 BGB show that forms of acquisition without direct possession of the buyer or seller are not alien to the BGB. Security interests of the intermediary speak against the direct acquisition of the first seller to the last buyer. It is not uncommon for a retention of title to be agreed in the case of drop shipping. The secondary seller therefore has a considerable economic interest in acting as a seller himself. But he would lose this security if a direct acquisition between the first seller and the last buyer were accepted. As a rule, the seller of the first stage does not know the reasons why he is delivering to a third party, so that the acceptance of approval or approval of the intermediary's disposal appears to be constructed. Ultimately, this solution corresponds to the relativity of the obligations, according to which the reversal of legal transactions takes place within the respective closed causal relationship.

Sham acquisition

The recognition of a so-called “sham acquisition” is also controversial. This is understood to be a case of acquisition in good faith in which there is actually no instructional relationship in the sense of acquiring bid. Rather, the alleged wise man would like to fulfill his or her own obligation. The other person understands the appearance of the person who hands over or accepts the thing as if it were done at the behest of someone else. The BGH has repeatedly recognized the purchase in good faith from a sham person.

However, there is also criticism of this case law. It is argued against the recognition of the sham that there is no sufficient legal certificate . Only the good faith in "the existence of the legal record holder" is not protected. The rules of good faith demanded "more" from the entitled person compared to the acquisition. This more can be seen in possession, so that a mere power to procure property is not enough.

For the recognition of the bogus acquisition, it is argued that the legal certificate of a bid to be assigned to the original owner. It is up to him to clarify the situation. There is the legal appearance of a property procuring power. The recognition of the mock bid is consistent if one considers the bid to be permissible. Furthermore, the recognition of the sham acquisition correlates with the prevailing concept of performance, according to which, in case of doubt, the point of view of an objective recipient in the specific position of the recipient of the service is important. Otherwise an unreasonable situation arises, since the purchaser is exposed to condition claims of the person in charge according to § 816 BGB, against which he cannot counter the payment of the purchase price to the first seller, i.e. has to pay twice.

See also

literature

- Franz-Josef Kolb: acquiring bid. A determination of position in the field of tension between the traditional principle and the need for traffic . Publishing house Peter Lang, Frankfurt a. M. 1996.

- Michael Martinek : The principle of tradition and acquiring authority . Archives for civilist practice (AcP) 188 (1988), pp. 573-648

- Elmar Wadle : The handover at the behest and the legal acquisition of the property . Juristentung 1974, pp. 689-696

- Ernst von Caemmerer : Transfer of ownership through instruction for transfer . Juristentung (JZ) 1963, pp. 586-588

- Werner Flume : Acquisition of property with services in a triangular relationship , in: Festschrift for Ernst Wolf, Carl Heymanns Verlag Cologne / Berlin / Bonn / Munich 1985, pp. 61–71.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michael Martinek : AcP 188 (1988), 573, 600.

- ^ In detail on terminology Martinek, AcP 188 (1988), 573.

- ↑ BGH, judgment v. November 9, 1998 - II ZR 144/97 , NJW 1999, 425; see also BGH, judgment v. June 4, 1969 - VIII ZR 163/67 , MDR 1969, 749.

- ↑ See Martinek, AcP 188 (1988), 573 (601); see also example cases at Medicus / Petersen : Bürgerliches Recht , 23rd edition 2011, marginal no. 563.

- ↑ BGH, judgment v. March 22, 1982 - VIII ZR 92/81 , NJW 1982, 2371.

- ↑ Henssler in Soergel Commentary on the BGB , 13th edition 2011, 14th volume, § 929 Rn. 63.

- ^ Baur : Textbook of Property Law , 7th edition 1973, p. 440.

- ^ Wadle : JZ 1974, 689 (693).

- ↑ Ernst von Caemmerer , JZ 1963, 586 (587); Flume in: Festschrift Wolf, 1985, p. 61 (64).

- ↑ Ennecerus / Wolff / Raiser : Textbook of Property Law , 10th edition 1957, § 66 I 1 a a.

- ↑ Matinek AcP 188 (1988), 621.

- ↑ Wadle, JZ 1974, 689 (694).

- ↑ Gursky , JZ 1984, 604 (606).

- ↑ Matinek, AcP 188 (1988) 599.

- ↑ Henssler, in: Soergel Commentary on the BGB , 13th edition 2011, 14th volume, § 929 Rn. 63.

- ↑ Matinek, AcP 188: 615; Henssler, in: Soergel Commentary on the BGB , 13th edition 2011, 14th volume § 929 marginal no. 63.

- ↑ BGH, judgment v. October 30, 1961 - VII ZR 218/60 , BGHZ 36, 56; BGH, judgment v. November 8, 1972 - VIII ZR 79/71 , NJW 1973, 141; BGH, judgment v. March 14, 1974 - VII ZR 129/73 ( Memento of the original from July 18, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , NJW 1974, 1132.

- ↑ Ernst von Caemmerer, JZ 1963, 586 (587 f.); Ulrich von Lübenow : Festschrift of the Faculty of Law of the Free University of Berlin for the 41st German Lawyers' Day , 1955, 119 (208 ff.); Wolf : Textbook of Property Law , 2nd edition 1979, p. 239; Flume, in: Festschrift Wolf , 1985, p. 61 (69).

- ↑ Medicus / Petersen Bürgerliches Recht 23rd edition. 2011, Rn. 564.

- ↑ Wadle, JZ 1974, 689 (694).

- ↑ Wiegand : Staudinger BGB , §§ 925–984, appendix to §§ 929 ff., Revised 2011, § 923, marginal no. 18-25.

- ↑ Westermann / Gursky / Eickmann: Sachrecht , 8th edition 2011, p. 426 ff.

- ↑ Wieling , JZ 1977, 291.