Intercisa burial grounds

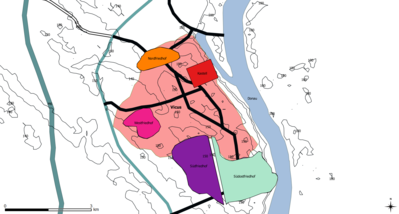

The Intercisa burial grounds are part of the Intercisa site, which also includes the Intercisa fort and a vicus . The site is on a plateau in the former province of Pannonia inferior on the Danube Limes ( Limes Pannonicus ), in the area of the city of Dunaújváros in Fejér County in today's Hungary . So far, four necropolis are known, the so-called Great Necropolis in the south of the plateau, the Southeast Necropolis, which adjoins the Great Necropolis to the east, the North Necropolis and the West Necropolis. The burials consist of cremation and body graves .

Fig. 1: Location of the Intercisa site |

location

Today's town of Dunaújváros is located about 70 km south of Budapest , directly on the Danube . The former border post Intercisa located here is located on a plateau consisting of the two mountains Kálváriához (Calvary) in the northern part and Öreghegy ("Old Mountain") in the southern part. This area, surrounded by two streams, is at its highest point in the north at 142 m above sea level. Because the loess edge in the east of the plateau was eroded further and further for centuries by the submergence of the Danube, at least 50 meters of the original width and thus parts of the fort and the burial grounds were lost. After the Danube was relocated to the east, the former course can still be seen in the form of an oxbow lake.

Research history

In 1906, Ede Mahler was entrusted by the Hungarian National Museum with the first official archaeological measures in Dunapentele in order to counteract the increasingly frequent robbery excavations caused by the growing popularity of the site among art and antique dealers. The primary goal was to document and map the ancient remains, but as early as 1907 Mahler carried out further excavations in the southern burial ground and also compiled a catalog of the already known memorial inscriptions from Intertcisa. From 1908 onwards, Antal Hekler was responsible for the excavations. It is thanks to him that the first classification of finds and findings at the archaeological site according to graves with a brief description of each is to be thanked. Hekler also changed the focus of research away from the areas of the burial grounds that were already known from looting towards his own research excavations. Under the direction of the Hungarian National Museum, over 800 graves were discovered and documented, mostly in the area of the southern cemetery, by 1911.

Further excavations were only possible after the First World War. They were carried out by Zoltán Oroszlán in 1922 , but are only available as a preliminary report. The Roman graves discovered in this excavation and some of which had already been plundered, however, made it possible to date them to the post-Valentine period through coin finds. As a result, further systematic studies were carried out by István Paulovics from 1926 and presented in a first scientific monograph. Paulovics not only included previous research, but also described the findings and findings in detail and illustrated them in a detailed illustration. His connecting work is thus an important advance in research in Hungary for its time.

Due to extensive state construction work and ongoing erosion of the Danube bank, further archaeological measures were necessary between 1949 and 1952. For the first time in Hungary aerial photography was used as a planning aid. A research group led by László Barkóczi was entrusted with the excavations and published them in two volumes in 1954 and 1957. In the 1960s, the urban expansion of the community, now renamed Dunaújváros, led to further rescue excavations that lasted until 1967 and were carried out under Eszter B. Vágó were. The focus was on the Roman fort, the civil settlement and the burial grounds. In total, over 1500 graves in the north and south-east cemetery were uncovered in the 1960s, of which over 800 come from the south-east cemetery and have been researched and published as a contiguous area (Fig. 4 and 5). From the 1970s on, excavations were carried out in the Roman cemetery on a smaller and smaller scale. In 1974 it became possible to subdivide the so-called large necropolis in the south into two areas, separated by the Roman road, called the south and south-east cemetery (Fig. 3). In 1980 the Westfriedhof was discovered as the only largely untouched cemetery.

The burial grounds

The cemetery area is grouped in four units around the fort (Fig. 2). A necropolis in the north, one in the west, one in the south ("Great Necropolis") and then one in the southeast of the plateau. No information can be given about the exact location of the graves in the first three areas, as no grave field plans were drawn up for this.

The large necropolis in the south, which also includes the oldest burials, was initially on the western side of the Limes Road (Fig. 3). The cremation graves here go back to the time of the Marcomann Wars (2nd half of the 2nd century AD). It was not until the 3rd century AD that the necropolis expanded to the east along the Limes Road, and these are now body graves. The square was used until the 5th century.

In the 4th / 5th There are new burial places north and west of the fort. The so-called northern necropolis is delimited by the slope edge in the north, the fort in the south and the Princesor Gorge in the west. The western necropolis is located on a presumed ancient path west of the fort, in the former area of the vicus. Furthermore, a building with an apsidal closure was discovered here east of the cemetery, for which an early Christian use is suggested. In addition, there are burials of Germanic new settlers from the post-Valentian era in this area, which indicate a burial ground in the south-west corner of the vicus.

The last burial ground is the area of the southeast cemetery, delimited by Esther Vágó. This is bounded in the east by the loess bank of the Danube and in the south by the "Great Gorge" (Nagy-szakadék). In the west, the stone grave 33 in the NE corner of building L12 forms the end (Fig. 4), in the north a strip of land which separates the south-east necropolis from the south necropolis. This, as the only one of the four known published cemeteries, has around 800 burials. These are divided into cremation burials and the vast majority (three quarters of all graves) body burials . In the case of cremation burials, fire pit graves predominate, in which the corpse burn and the remains of the pyre are scattered in an (urnless) pit. In the case of body burials, earth , brick and stone box graves dominate (Fig. 5). Of these late antique body burials, those with brick cover predominate, followed by the simple earth graves. As a result of the looting and destruction of the graves, which can mainly be ascribed to the excavations of the antique dealers, numerous finds found their way not only into the National Museum in Hungary, but also beyond the borders of Hungary.

Stone monuments

Antique trade

Since the end of the 19th century there have been various purchases of found material from Intercisa. Most of the finds in the collections come from the southeast necropolis. Another part was recovered from excavations in the "Great Necropolis". As a result of the excavations carried out by the antique dealers at the time, which ran parallel to those of the Hungarian National Museum, the objects also ended up in that museum, but a considerable number of collections were sold outside of Hungary.

So also to Germany. The well-known institutions that made purchases with antique dealers were the Royal Museum of Ethnology in Berlin (today State Museums in Berlin - Prussian Cultural Heritage ), which came into possession of various found objects at the end of the 19th century, the Roman-Germanic Central Museum in Mainz , the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna as well as the Schröder collections of the University of Jena and the Sigmund Freud collection. Initially individual finds from Dunapentele were in the foreground of the robbery excavations, this increasingly developed into the sale of entire find complexes and grave inventories, of which it cannot be said with certainty that they have not been reassembled.

Important prehistorians of their time such as Friedrich Behn , Carl Schuchhardt and Alfred Götze were responsible for the acquisition and research work with the objects collected in this way , whereby they set different priorities in their respective collection activities. In Mainz and Vienna, for example, the ceramics of Roman Pannonia, with material largely derived from Intercisa, clearly emerged. This resulted, for example, in the type table for Roman ceramics created by Friedrich Behn in Mainz in 1910 from the holdings of the collection. In all three of the museums mentioned above, special attention was also paid to objects that were clearly identifiable both typologically and chronologically.

photos

Gravestone of a local couple, Demiuncus and his wife Angulata. Today in the Hungarian National Museum. (See also: Roman stone monuments from Intercisa )

literature

- Eszter B. Vágó , István Bóna : The grave fields of Intercisa I. The late Roman southeast cemetery (= Eszter B. Vágó (Ed.): The grave fields of Intercisa. Volume 1). Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1976, ISBN 963-05-0743-9 .

- László Barkóczi , Ferenc Fülep , Maria Radnoti-Alföldi u. a. (Ed.): Intercisa I. (Dunapentele-Sztálinváros). History of the city in Roman times. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1954.

- Maria Radnoti-Alföldi (Eds.), László Barkóczi, Jenő Fitz u. a .: Intercisa II. (Dunapentele). History of the city in Roman times. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1957.

- Felix Teichner : The grave fields of Intercisa II. The old finds of the museum collections in Berlin, Mainz and Vienna (= Matthias Wemhoff (Hrsg.): Museum for Pre- and Early History inventory catalogs. Volume 11). National Museums in Berlin - Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-88609-716-6 .

Web links

- Inventory books of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum

- Website of the Dunaújváros City Museum

- Academia link to the work of Felix Teichner, 2011

Individual evidence

- ^ Felix Teichner: The grave fields of Intercisa II. The old finds of the museum collections in Berlin, Mainz and Vienna. (= Matthias Wemhoff (Hrsg.): Museum for Pre- and Early History inventory catalogs Volume 11). Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-88609-716-6 , pp. 19-20.

- ^ Felix Teichner: The grave fields of Intercisa II. The old finds of the museum collections in Berlin, Mainz and Vienna. (= Matthias Wemhoff (Hrsg.): Museum for Pre- and Early History inventory catalogs Volume 11). Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-88609-716-6 , pp. 29-30.

- ^ Felix Teichner: The grave fields of Intercisa II. The old finds of the museum collections in Berlin, Mainz and Vienna. (= Matthias Wemhoff (Hrsg.): Museum for Pre- and Early History inventory catalogs Volume 11). National Museums in Berlin - Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-88609-716-6 , pp. 30–31.

- ↑ László Barkóczi, Ferenc Fülep , Maria Radnoti-Alföldi u. a .: Intercisa I. (Dunapentele-Sztálinváros). History of the city in Roman times. (= Barkoczi (Ed.): Archaeologia Hungarica Volume 33). Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1954.

- ^ Eszter B. Vágó / István Bóna: The grave fields of Intercisa I. The late Roman southeast cemetery. (= Eszter B. Vágó (Hrsg.): The grave fields of Intercisa Volume 1). Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1976, ISBN 963-05-0743-9 .

- ^ Felix Teichner: The grave fields of Intercisa II. The old finds of the museum collections in Berlin, Mainz and Vienna. (= Matthias Wemhoff (Hrsg.): Museum for Pre- and Early History inventory catalogs Volume 11). State Museums in Berlin - Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-88609-716-6 , p. 34.

- ^ Felix Teichner: The grave fields of Intercisa II. The old finds of the museum collections in Berlin, Mainz and Vienna. (= Matthias Wemhoff (Hrsg.): Museum for Pre- and Early History inventory catalogs Volume 11). National Museums in Berlin - Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-88609-716-6 , p. 24.

- ^ Felix Teichner: The grave fields of Intercisa II. The old finds of the museum collections in Berlin, Mainz and Vienna. (= Matthias Wemhoff (Hrsg.): Museum for Pre- and Early History inventory catalogs Volume 11). National Museums in Berlin - Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-88609-716-6 , pp. 24-25.

- ^ Felix Teichner: The grave fields of Intercisa II. The old finds of the museum collections in Berlin, Mainz and Vienna. (= Matthias Wemhoff (Hrsg.): Museum for Pre- and Early History inventory catalogs Volume 11). National Museums in Berlin - Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-88609-716-6 , p. 25.

- ^ Eszter B. Vágó / István Bóna: The grave fields of Intercisa I. The late Roman southeast cemetery. (= Eszter B. Vágó (Hrsg.): The grave fields of Intercisa Volume 1). Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1976, ISBN 963-05-0743-9 , p. 122

- ↑ László Barkóczi, Ferenc Fülep, Maria Radnoti-Alföldi u. a .: Intercisa I. (Dunapentele-Sztálinváros). History of the city in Roman times. (= Barkoczi et al. (Ed.): Archaeologia Hungarica Volume 33). Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1954, pp. 121-123.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: On the terminology of Roman provincial cremation graves. (Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum (Hrsg.): Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt Volume 10, 1980). Publishing house of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz, Wiesbaden 1980, ISSN 0342-734X, pp. 253-254.

- ^ Eszter B. Vágó / István Bóna: The grave fields of Intercisa I. The late Roman southeast cemetery. (= Eszter B. Vágó (Hrsg.): The grave fields of Intercisa Volume 1). Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1976, ISBN 963-05-0743-9 , p. 141

- ^ Eszter B. Vágó / István Bóna: The grave fields of Intercisa I. The late Roman southeast cemetery. (= Eszter B. Vágó (Hrsg.): The grave fields of Intercisa Volume 1). Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1976, ISBN 963-05-0743-9 , p. 141

- ^ Eszter B. Vágó / István Bóna: The grave fields of Intercisa I. The late Roman southeast cemetery. (= Eszter B. Vágó (Hrsg.): The grave fields of Intercisa Volume 1). Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1976, ISBN 963-05-0743-9 , p. 154

- ^ Eszter B. Vágó / István Bóna: The grave fields of Intercisa I. The late Roman southeast cemetery. (= Eszter B. Vágó (Hrsg.): The grave fields of Intercisa Volume 1). Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1976, ISBN 963-05-0743-9 , pp. 153-156

- ^ Felix Teichner: The grave fields of Intercisa II. The old finds of the museum collections in Berlin, Mainz and Vienna. (= Matthias Wemhoff (Hrsg.): Museum for Pre- and Early History inventory catalogs Volume 11). Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-88609-716-6 , pp. 40–58.

- ^ Felix Teichner: The grave fields of Intercisa II. The old finds of the museum collections in Berlin, Mainz and Vienna. (= Matthias Wemhoff (Hrsg.): Museum for Pre- and Early History inventory catalogs Volume 11). National Museums in Berlin - Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-88609-716-6 , pp. 268–269.