Hamlet (sources)

This article discusses in detail what sources Shakespeare used in composing his play Hamlet .

Ancient and Nordic legends and their tradition

Lucius Brutus

Shakespeare may have used motifs from the legend of Lucius Junius Brutus in Hamlet . The founder of the Roman Republic (509 BC) avenged the murder of his father and his brother by Tarquinius , whom he deceived by pretending to be stupid. It is uncertain whether Shakespeare knew this legend, including the already pronounced motif of disguising the clever, as stupid. Perhaps he had access to the first book of Titus Livius ' Ab urbe condita libri , which was published in an English translation by Philemon Holland in 1600 , or he knew the story from Ovid's Fasti . The Lucius Brutus legend found an echo in other plays by Shakespeare, including Julius Caesar , Henry V and Lucretia .

Oedipus and Orestes

As early as 1897, in a letter to Fliess, Freud placed Hamlet next to Oedipus and suggested that Shakespeare's unconscious had shaped his hero's unconscious as the story of an Oedipal conflict. Other authors argue that the story of Orestes is more similar to that of Hamlets than the story of Oedipus. Agamemnon and Clytaimnestra are the parents of Orestes. Agamemnon goes to war, his wife does not want to wait for his return and marries a suitor, Aigisthos. When Agamemnon returns, Aigisthus kills the homecomer. Orestes avenges his father by killing the murderer and his mother. For this he is beaten madly by the Erinyen . The motives of the unfaithful mother, the murderous brother and the avenging son are much more obvious here than in Oedipus.

Amlethus

When asked about the name of the piece and the main features of the plot, a Nordic tradition is consistently pointed out. These include the first reports on Amleth in the Snorra Edda by the Icelandic Snorri Sturluson . In the third part of the Prose Edda, the Skáldskaparmál , Snorri mentions the image ( kenning ) of the sea as Amlodi's mill.

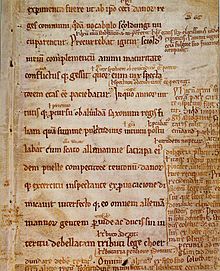

The story of Amlethus is further processed in the Gesta Danorum of Saxo Grammaticus , which was probably written around 1185. Four fragments of the work have been preserved: the Angers fragment, the Lassen fragment, the Kall-Rasmussen fragment and the Plesner fragment. The Angers fragment is the oldest and dates from around 1200. It consists of four completely written parchment leaves and is considered to be the Saxo manuscript. The three other fragments are copies from the second half of the 13th century. They are all in the Royal Library in Copenhagen.

The fragments of the Gesta Danorum from the 13th century are incomplete. However, it is completely preserved in a Latin version from the 16th century. It is the Danorum Regum heroumque Historia , which Christiern Pedersen wrote in Paris in 1514. The Amlethus story contained therein was translated into French by François de Belleforest and published in 1570 for the first time in the fifth volume of the Histoires tragiques . This work is a joint effort by Belleforest and Pierre Boaistuau . He translated six short stories by Matteo Bandello from Italian into French and published them for the first time in 1559. Belleforest then added twelve more stories to the 1570 version, one of which is the Amlethus saga. When Belleforest reworked the Amlethus story, he reintroduced the hero's melancholy element and deepened and expanded the misogynous elements that were already inherent in Saxo. At the same time, Belleforest supplemented his template with cumbersome moralizing comments, so that the scope of the original text almost doubled. The French version of the Histoires tragiques appeared in seven editions until 1601. In 1608, Belleforest's Amleth story appears for the first time in an English translation as The Hystorie of Hamblet .

The story of Amlethus told by Saxo Grammaticus already shows clear similarities with the plot of Shakespeare's Hamlet. For example, various moves such as faking insanity or the conversion of the killing orders during the trip to England are sketched out, although the protagonist is not shown here as a hesitant, thoughtful person, but purposefully pursues his plan of revenge with clever cunning.

Belleforest's version of the Amleth story also contains other changes and additions that are quite interesting for Shakespeare's Hamlet. Fengon, for example, slept with his brother's wife while his brother was alive, see the words of the spirit in Hamlet, scene I.5: “Don't let Denmark's royal bed be a bed for incest and wicked lust!” In addition, Gerluth's marriage is crowded Increasingly asked questions with Fengon whether she had known about the murder or had even planned it in order to be able to live out her relationship with Fengon undisturbed. Amleth accuses this, similar to Hamlet in scene III.1, in a passionate, rhetorically polished address to his mother, which she in turn denies. As with Shakespeare, Amleth's mother swears to keep Amleth's secret and advises him to seek revenge and ascend the throne himself.

While some of the Shakespeare researchers suspect that Belleforest's translation into English could have been available earlier and thus would be a likely main source for Shakespeare in question, other scholars take the view that the English translation of Belleforest shows clear knowledge of Shakespeare's Hamlet with it could only have emerged afterwards and for this reason completely ruled out as a possible source for Shakespeare's work.

Contemporary plays

Ur-Hamlet and Spanish Tragedy

The second source problem revolves around the assumption of a contemporary theater play on which the composition of Hamlet is based, with two main candidates being brought into play: the Spanish tragedy written by Thomas Kyd and the hypothetical original Hamlet, also ascribed to Kyd . See the section Immediate Precursors of Shakespeare's Hamlet .

The involuntary confession of a murderess

In 1599 Shakespeare's theater company staged the play A Warning for Fair Women by an anonymous author. It tells the story of a husband murderer who watches a play in which the husband's ghost haunts the murderer.

It says:

- She was so mooved with the sight thereof,

- As she cryed out, the Play was made by her,

- And openly confesst her husbands murder.

- She was so moved by watching [the play]

- that she shouted that the play was about her,

- and she confessed to the murder of her husband.

Various authors hold this play as a source for Hamlet's plan to convict King Claudius by means of a play.

The Murder of Gonzago

A fictional contemporary play appears at Hamlet. There are various references to the title of this play in the play in the literature of Shakespeare's time. According to contemporary statements, Francesco Maria I della Rovere was murdered in 1538 by having poison poured into his ear. His murderer was Luigi Gonzago, his wife's lover. There is a portrait of Titian by della Rovere, which is similar to the description of the ghost of Hamlet's father. Other authors have suggested that knowledge of a connection between the ear and the throat may have been influenced by the discovery of the eustachian tube in 1564. The idea of the "Neapolitan method" can be found in Marlowe's Eduard II.

Contemporary poetry

The aged lover rounceth love

In scene V.1 (lines 61-97) in Hamlet, the first grave digger sings a song while digging the grave for Ophelia's funeral, in which three stanzas from the poem The aged lover rounceth love (dt. The aging lover swears off love ) by Thomas Vaux, 2nd Baron Vaux of Harrowden (1509-1556):

- In youth, when I did love, did love,

- Methought it was very sweet,

- To contract-O-the time for-a-my behove,

- O methought there-a-was nothing-a-meet.

- But age, with his stealing steps,

- Hath caught me in his clutch,

- And hath shipped me intil the land,

- As if I had never been such.

- A pickaxe and a spade, a spade,

- For and a shrouding sheet:

- O, a pit of clay for to be made

- For such a guest is meet.

The German translation in the version by August Wilhelm von Schlegel reads:

- When I was young I do love

- That seemed so cute to me.

- To spend the time, oh morning and late,

- I didn't like anything like this.

- But age with the creeping step

- Grabbed me with his fist

- And shipped me out of the country

- As if I had never stayed there.

- A graveyard and a spade,

- With a linen smock,

- And oh, a pit, deep and hollow,

- Must be for such a guest.

The poetic model by Lord Thomas Vaux appeared posthumously in print in 1557 in Tottel's Miscellany , the first printed and then famous anthology of poems, published by the London bookseller and publisher Richard Tottel, son-in-law of the well-known printer Richard Grafton .

Philosophical motives and themes

Many scholars have tried to identify the sources of individual motifs and details in Hamlet . With the motif of the prince reading books, reference is often made to the question of which contemporary philosophical literature Shakespeare processed in Hamlet.

Montaigne

In Hamlet , there are echoes of contemporary and antique philosophical works. Since Edward Capell , Montaigne has been brought into play again and again . In more recent work, the relationships between the thinking of Montaigne and Shakespeare have been discussed intensely. The French Anglicist Robert Ellrodt , for example, pointed out close parallels in content between six passages in Hamlet on the one hand and three essays by Montaigne. The idea, mentioned several times in Hamlet, that a ruler is only a meal for worms, refers to the “Apologie de Raymond Sebond” (Essais, Book 2, Chapter 12.). Other authors have been critical of Shakespeare's assumption of a reception of Montaigne. In the most recent Arden edition, Thompson and Taylor point out that the essays were published between 1580 and 1588, but that an English translation by John Florio did not appear until 1603. However, Sir William Cornwallis (the father of Frederick Cornwallis ) mentioned in 1600 that he had read Montaigne in English, and it is believed that this was Florio's translation, which he worked on from 1598. So Shakespeare could have known this. Individual subjectivist formulations: [...] for there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so - [...] because nothing is either good or bad, only thinking makes it so. , in which one can see an echo of the opening sentence of Montaigne's Essay XL, is viewed by Thompson and Taylor as a variant of a commonplace wisdom : A man is weal or woe as he thinks himself so. (Basically: whether you are lucky or unlucky depends on your point of view).

Pico della Mirandola, Cicero and others

Hamlet's famous speech about human dignity: What a piece of work is a man [...] - What a masterpiece is a person [...], says W. Müller as Pico della Mirandola 's Oratio de hominis dignitate. modeled on. Ronald Knowles also does not believe that Montaigne's “Apologie de Raymond Sebond” was the model for the speech, but rather the writings Bref discours de Lexcellence et dignité de l'homme. (1558) and Le Théâtre du monde, où il est fait un ample discours des misères humaines. (1561) by Pierre Boaistuau , translated into English by John Alday in 1566 and 1574 . When asked about the reception of other authors, the opinions of the scholars do not differ so much. The greeting of Horatios by Hamlet: Sir, my good friend, I'll Change that name with you. - Sir, my good friend, I want to change this name with you. is seen as an expression of a politeness strategy based on Cicero's speech about friendship and an example of the use of “in-group identity markers”. The denunciation of social grievances in the "To be or not to be" monologue: For who would bear the whips and scorns of time [...] ("Because who would endure the blows and the ridicule of time ...") is made by individual authors regarded as inspired by Thomas More or Erasmus of Rotterdam .

Content comparison between Hamlet and its sources

Historiae Danicae

Amleth's father slew the Norwegian king in a duel and is murdered by his brother Feng. Feng marries Gerutha, his brother's widow. The murder does not happen in secret. Amleth pretends to be insane, walks in ragged clothes, sits by the fire and makes hook-shaped sticks, but seems implausible. Therefore he is subjected to rehearsals. The first test is to confront him with a pretty woman. Amleth persuades them to maintain secrecy. Feng and a friend decide to eavesdrop on Amleth when he visits his mother. Amleth notices the spy, kills him, dismembles the corpse, and feeds the parts to the pigs. Then he returns to his mother and blames her for remarrying. Then Feng sends the amleth to England with company, along with a letter asking the English king to execute Amleth. Amleth replaces his name with that of the companion and adds that he will be married to the daughter of the English king. When he returns, he arranges a trap for the feudal people in the king's hall, sets a fire in the royal palace and kills Feng in his bed by using a swapped sword. Finally, he successfully defends himself before the people with a speech, is crowned king and is killed in battle.

Belleforest's version of the Hamlet saga

In Belleforest's version of the Hamlet saga, the pirate Horvendile kills the Norwegian King Collere. After returning to Denmark, he married the (widowed) Princess Geruth. His younger brother Fengon kills Horvendil and has an adulterous relationship with Geruth while Horvendile was still alive. Geruth has a son from his first marriage, Hamblet. He fears that he will become Fengon's next victim and therefore pretends to be insane to appear harmless. This is almost seen through, so traps are set for him. A pretty young woman is supposed to seduce him and spies eavesdrop on him in his mother's room. His mother supports Hamlet's plans for revenge, warns him and Hamblet murders Fengon in his bed by knocking his head off his shoulders. In the end, Hamblet defends himself against accusations of high treason. He declares that as the rightful heir to the throne, he has punished a disloyal subject.

Thomas Kyd - Spanish Tragedy

The most important elements of Thomas Kyd's Spanish tragedy are as follows: it is about the revenge of a father for his murdered son, the hero is insane, the ghost of a dead man appears and there is the play-in-play that relates to the main plot serves a similar purpose. The other, at least twenty structural parallels in total include the suicide of a woman, the appearance of a loyal friend named Horatio or a brother who kills his sister's lover. However, the differences are clear: in Shakespeare's Hamlet the son avenges the father, the The father's spirit demands vengeance and the hero's madness is set. An important correspondence between Hamlet and the Spanish tragedy is the occurrence of a second story of revenge in the play: the main motif is the desire for revenge of the spirit of the late Spanish officer Andrea against his murderer Balthazar. Balthazar was captured by Horatio and later murdered him. Horatio's father Hieronimo murders Balthazar while performing a play in a play. In this way, Andreas Geist's desire for revenge and Hieronimo's request are fulfilled.

Text output

English

- Harold Jenkins (Ed.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Second series. London 1982.

- Philip Edwards (Ed.). Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge 1985, 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-53252-5 .

- Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006, ISBN 978-1-904271-33-8 .

- Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Texts of 1603 and 1623. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 2, London 2006, ISBN 1-904271-80-4 .

English German

- Norbert Greiner, Wolfgang G. Müller (Eds.): Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-86057-567-3 .

supporting documents

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 64.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 26. (Garber 124-71)

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 64.

- ↑ George Richard Hibbard (Ed.): Hamlet. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, 2008. p. 6.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales Volume 6. p. 424, article "Hamlet" by Werner Bies.

- ↑ Olin H. Moore, The Legend of Romeo and Juliet (The Ohio State University Press, 1950), chapter X: Pierre Boaistuau ( Memento of the original from July 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. pp. 67f. Cf. also Ina Schabert: Shakespeare-Handbuch. Time, man, work, posterity. Kröner, Stuttgart 1972, ISBN 3-520-38601-1 (5th, revised and supplemented edition, ibid. 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 ), p. 528. See also Günter Jürgensmeier (ed.): Shakespeare and his world. Galiani, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3869-71118-8 , p. 427. In contrast to other sources, Jürgensmeier dates the first publication of the fifth volume of the Histoires tragiques Belleforests to 1572.

- ↑ George Richard Hibbard (Ed.): Hamlet. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, 2008. p. 6.

- ↑ See the reprint of the German translation of Amleth by Saxo Grammaticus in Günter Jürgensmeier (Ed.): Shakespeare und seine Welt. Galiani, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3869-71118-8 , pp. 428-440. See also Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 332.

- ↑ See Günter Jürgensmeier (Hrsg.): Shakespeare and his world. Galiani, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3869-71118-8 , p. 427 ff. As well as the copy of the German translation of Prince Amleth's address to Queen Geruthe, his mother , ibid p. 443-444. According to Jürgensmeier, however, Belleforest's version is very likely to be Shakespeare's main source, although he admits that this cannot be proven with complete certainty. He himself nevertheless regards Belleforest's version with a high degree of probability as Shakespeare's main source, although he admits that this cannot be proven with complete certainty (p. 427).

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 60.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Texts of 1603 and 1623. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 2, London 2006. p. 482.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 61.

- ↑ Geoffrey Bullough (Ed.): Narrative and Dramatic Sources of Shakespeare. 8 volumes, London and New York 1957-1975. Volume 7, p. 33.

- ↑ Avrim R. Eden, Jeff Opland: Bartolommeo Eustachio's 'De Auditus Organ' and the unique murder plot in Shakespeare's Hamlet. The New England Journal of Medicine, 307, July 22, 1982. pp. 259-261.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 62.

- ↑ Cf. Günter Jürgensmeier (ed.): Shakespeare and his world. Galiani, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3869-71118-8 , p. 437. See also the entry Vaux of Harrowden, Thomas Vaux, 2nd Baron in the Encyclopædia Britannica from 1911, online on Wikisource [1] . Accessed on August 16, 2020. The text of the first print of The aged lover rounceth love is available online as a PDF file on WordPress in an edition of Tottel's Miscellany from 1890 (here p. 173 f.) [2] . Retrieved on August 16, 2020. In the text version of the first quarto edition of Hamlet , instead of the three stanzas of the song in the first folio edition, there is a version shortened to two stanzas. See William Shakespeare: Hamlet. Edited by Harold Jenkins. The Arden Shakespeare. Methuen 1982, reprint 2001 by Thomas Learning, Introduction , p. 27 f.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 61.

- ↑ Capell, E .: Mr. William Shakespeare. His Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies. 10 volumes, London 1767-68.

- ^ Hugh Grady: Shakespeare, Machiavelli, and Montaigne: Power and Subjectivity from Richard II to Hamlet. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2002. Graham Bradshaw, Tom Bishop: The Shakespearean International Yearbook: Special Section, Shakespeare and Montaigne Revisited: 6. Ashgate Publishing Limited 2006.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. II, 1, 59-62; II, 1, 82-87; IV, 3, 19-24; IV, 3, 39-42; V, 2, 10f and V, 2, 200f.

- ↑ Montaigne Essais, 2nd book: “We taste nothing purely”, “Against idleness, or doing nothing” and “Of bad menas employed to a godd end”.

- ^ Robert Ellrodt: Self-consciousness in Montaigne and Shakespeare. Shakespeare Survey 28 (1975) 37-50.

- ^ Norbert Greiner, Wolfgang G. Müller (eds.): Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 2008. IV, 3, 30f. Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. VI, 3, 30f. Nothing but to show you how an king may go a progress through the guts of a beggar. - Nothing, [I want] only to show how a king can go on a state tour through the bowels of a beggar.

- ^ Norbert Greiner, Wolfgang G. Müller (eds.): Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 2008. (Comment VI.3) p. 499.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 73.

- ^ Norbert Greiner, Wolfgang G. Müller (eds.): Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 2008. II, 2, 248f. Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. II, 2, 284. Norbert Greiner, Wolfgang G. Müller (Eds.): Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 2008. (Comment II.2) p. 459.

- ^ Montaigne's essays

- ^ William Shakespeare: Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Edited by Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor. Volume one. London 2006: p. 466.

- ^ Norbert Greiner, Wolfgang G. Müller (eds.): Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 2008. II, 2, 300ff. Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. II, 2, 269ff.

- ^ Norbert Greiner, Wolfgang G. Müller (eds.): Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 2008. (Comment II.2) p. 460.

- ^ Ronald Knowles: Hamlet and counter-humanism. in: Renaissance Quarterly, 52 (1999), 1046-69.

- ^ Norbert Greiner, Wolfgang G. Müller (eds.): Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 2008. I, 2, 163. Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. I, 2, 163.

- ^ Norbert Greiner, Wolfgang G. Müller (eds.): Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 2008. (Comment I.2) p. 434. Roger Brown and Albert Gilman: Politeness Theory and Shakespeare's Four Major Tragedies. in: Language in Society 18 (1989) pp 159-212; Quotation p. 167.

- ^ Norbert Greiner, Wolfgang G. Müller (eds.): Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 2008. III, 1, 70. Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. III, 1, 69.

- ^ Norbert Greiner, Wolfgang G. Müller (eds.): Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 2008. (Comment III.1) p. 4471.

- ↑ Philip Edwards (Ed.). Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge 1985, 2003. p. 1. Geoffrey Bullough (Ed.): Narrative and Dramatic Sources of Shakespeare. 8 vols. London and New York 1957-1975. Vol. VII, pp. 69-79. Norbert Greiner, Wolfgang G. Müller (Eds.): Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 2008. P. 29f.

- ↑ Brown Handbook. Pp. 12-16. Philip Edwards (Ed.). Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge 1985, 2003. p. 2.

- ↑ Philip Edwards (Ed.). Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge 1985, 2003. p. 3.

- ↑ Philip Edwards (Ed.). Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge 1985, 2003. p. 4. See also Günter Jürgensmeier (Ed.): Shakespeare and his world. Galiani, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3869-71118-8 , p. 428.