Harvey Dunn

Harvey Dunn (born March 8, 1884 in Manchester , South Dakota , † October 29, 1952 in New York , New York ) was an American illustrator, painter and teacher. His best-known work is the painting The Prairie is my Garden from 1950 . However, Dunn made a name for himself as an illustrator before and during the First World War .

Life

Harvey Dunn was born on March 8, 1884 to farmers near Manchester, South Dakota . At 17, he left his parents' rural farm and enrolled at the South Dakota Agricultural College in Brookings , where he met art professor Ada Caldwell. His grades were mediocre, but Caldwell recognized his talent. With her help, he attended the Chicago Institute of Art . There he became a student of Howard Pyle . In 1906, Dunn opened his own studio in Wilmington , Delaware . At that time, his work was already enjoying great popularity. His illustrations in particular were featured in various magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post . In 1914 Dunn moved to Leonia , New Jersey , where he founded the Leonie School of Illustration the following year with the artist Charles S. Chapman . It was during that time in New Jersey, just before the United States joined World War I, that Dunn enjoyed his greatest successes as an illustrator.

First World War

In 1918, Dunn interrupted his successful career to join the American Expeditionary Forces on the Western Front of World War I in France. He was one of only eight Americans who took part in the war as illustrators. It was during this time that he created some of his most powerful and shocking illustrations. Dunn did not shy away from portraying the exhausting trench warfare in all its atrocities. In the picture on the right, for example, you can see a soldier who, despite all the pain, marches through a barbed wire fence. The fear is written on his face. And for this very reason he fights his way through the obstacle in pain. Dunn later said that the atrocities of war changed him forever. These were also the reason for a drastic change in his style as an artist in the following decades. As early as 1917, before he went to the front, Dunn created propaganda posters for the First World War, which can be seen in the selection of works. One of them reads (translation): “Victory is a question of strength. Sends - wheat, meat, fats, sugar. The fuel for our fighters. ”Two soldiers can be seen on this poster in front of a dreary winter landscape. The facial expression of the two is even more confident than in his later works during the war, which suggests that Dunn was not yet at the front at that time and that he had an even more positive image of the war.

Life after the war and work as a teacher

In 1919 he moved to Tenafly , New Jersey , where he opened a large studio near his home. He focused again on making promotional materials. According to Dunn, the impressions he gathered during World War I would have shaped the rest of his life and thus his work. Because when the dark memories came up, Dunn sought refuge in his memories of the peaceful life on the prairie in South Dakota, which he also captured in his pictures. Harvey Dunn not only taught at the Leonie School of Illustration , which he founded , but also at the Grand Central School of Art in New York City . Some of his students became successful painters and illustrators themselves. These include Dean Cornwell, John Clymer, Gerard Delano, Arthur Mitchell, Bert Proctor, Jack Roberts, Harold Von Schmidt, and Frank Street. Dunn was considered a strict teacher who asked a lot among his students. Dunn believed that talent alone was not enough. According to his students, he took a lot of time for each individual. Since many of his students already drew professionally, he hardly taught drawing techniques, but tried to inspire his students with words.

The later years

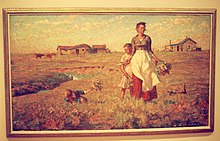

In his later years he mainly created paintings depicting simple prairie life in the Dakotas. Compared to other artists, these show no depictions of cowboys or Indians and their lives in the Wild West . Rather, his pictures deal with everyday life, activities and work that the rural residents of the Dakotas pursued during their childhood and youth. They are romanticized depictions of the simple life in the country. The picture on the right is probably Dunn's best-known work, The Prairie is my Garden . It shows a mother with her children picking flowers on a meadow in front of their house. Such images are typical of Dunn's late work. Not many of his paintings of life on the prairie have been sold. In 1950, he donated 42 of his paintings about the prairies of the Dakotas to the South Dakota Art Museum , where they can still be admired today.

Death and afterlife

Harvey Dunn died on October 29, 1952 in New York City at the age of 68. Many of his World War I illustrations belong to the Smithsonian Institution and are on display in their museums. A large number of his paintings hang in museums such as the South Dakota State Art Museum . His work is therefore publicly accessible. His name lives on at Harvey Dunn Elementary School , an elementary school in Sioux Falls , South Dakota .

Works (selection)

War posters and paintings

Harvey Dunn worked as an illustrator and drew propaganda posters for the US government prior to World War I. They called on people to send food to the soldiers at the front. The last picture was taken in 1918 when Dunn was stationed at the front in France to be one of only eight US illustrators to report on what was happening at the front. Dunn shows a very dreary and cruel picture of the war. That was typical of his illustrations from his time at the front. The terrible impressions he gathered here should drastically change him and thus also his art.

Illustrations and paintings after the First World War

After the First World War, Dunn concentrated mainly on his work as a teacher. He also began to paint more and more paintings.

Painting about prairie life in the Dakotas

The memories of rural life in South Dakota were, according to Dunn, a mental refuge from the horrors of war. The representations amounted to even then outdated household or work activities, which were to depict life in the prairies of the Dakotas during Harvey Dunn's childhood and adolescence. This painting is a case in point.

Web links

- South Dakota Art Museum . Retrieved February 16, 2018

- Illustrationhistory.org , accessed February 16, 2018

- The National Archives - The Unwritten Record Blogs , accessed February 16, 2018

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Gratz Gallery

- ^ A b Beyond Little House, The online home for Laura Ingalls Wilder Legacy and Research Association , accessed February 16, 2018.

- ↑ a b c d South Dakota Magazine , accessed February 16, 2018.

- ^ The New York Times , accessed February 16, 2018.

- ^ A b New York Gard Gallery , accessed February 16, 2018.

- ↑ Harvey Dunn Elementary School , accessed March 9, 2018.

- ↑ American Illustration , accessed March 9, 2018.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Dunn, Harvey |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American illustrator, painter, and teacher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 8, 1884 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Manchester , South Dakota |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 29, 1952 |

| Place of death | New York , New York |