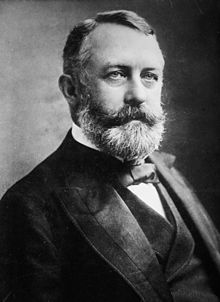

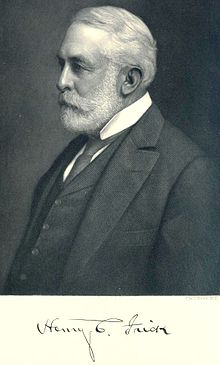

Henry Clay Frick

Henry Clay Frick (born December 19, 1849 in West Overton , Pennsylvania , † December 2, 1919 in New York City ) was an American industrialist of German-Swiss descent.

Youth and job

Henry Clayton Frick was the son of John Wilson and Elizabeth (Overholt) Frick. His father had Swiss and his mother German ancestors. He still had three sisters and two brothers. In the summer months he had to help out on the farm and in winter it was time for school. At age 14, he was an apprentice at the Overholt, Shallenberger and Company grocery store in Mount Pleasant, Pa. and when he was 19, he learned bookkeeping at his grandfather's Overholt's Flouringmill and Distillery in Broad Ford, Pa., the center of the Connellsville region's coal district. With a foresight that is unusual at such a young age, he recognized the possibilities that lay in the exploitation of the coal deposits with regard to the growing ironworks in Pittsburgh.

In 1871 the young Frick founded the company "Frick and Company" with Abraham O. Tintsman, one of his grandfather's partners, and Joseph Hist. They operated a coking plant and owned 300 acres of coal-bearing land and 50 coke ovens. At that time there weren't even 400 ovens in the whole Connellsville area, which totaled 100 square miles. In the following year Frick and Company built 150 more coke ovens. Frick was also one of the designers of the Mount Pleasant and Broad Ford Railroad, which was built around that time. He also built roads to transport the coal to the ovens. During the financial crisis of 1873 the banker Thomas Mellon, whom Frick was able to convince by his courage, granted him a loan which enabled him to either buy or lease all those works with the land of his fearful competitors, including the Shares of his business partners, so that he was the sole owner of "Frick and Company" until 1876.

Participation of Carnegie Bros. and Company Ltd

Frick was in the coke and steel business. He became a millionaire at the age of 30. Among other things, he supplied the company of the steel magnate Andrew Carnegie with coke and in 1881 merged his company with that of his best customer up to that point. His company, under his masterly leadership, had 1,026 stoves and 3,000 acres of coal land. The company was reorganized with a capital of $ 2,000,000, and increased to $ 3,000,000 a year later to keep up with the growing business. In 1889 the capital was further increased to $ 5,000,000 and the HC Frick Coke Company owned and controlled 35,000 acres (approximately 15,000 hectares) of Coal Land d. H. nearly 2/3 of the 15,000 furnaces in Connellsville, plus three waterworks pumping 5,000,000 gallons per day, 35 miles of railroad, and 1,200 coke cars. They employed 11,000 workers and the shipment of coal and coke amounted to 1,100 wagons a day. He was called the "Coke King".

By buying David A. Stewart's stake in 1889, Frick became the second largest shareholder in Carnegie Bros, and Company, Ltd. and elected as chairman. He became director of Carnegie, Phipps and Company and continued the presidency of HC Frick Coke Company, from which he had previously resigned.

He was most successful in buying a competitor, Duquesne Steel Works, by not spending a single dollar. He issued bonds for a total of $ 1,000,000 on the purchase, and the work had amortized itself within a year. It soon became the most modern and best equipped steel mill in the country. In addition, the labor-saving devices ensured that the cost of a ton of iron produced was only as much as 1½ tons elsewhere.

In 1892 all Carnegie holdings - with the exception of coke - were merged into the "Carnegie Steel Company, Ltd." summarized and Frick was elected chairman of this company. His plans for the union, which he had long considered, were now a reality. In this way, not only was the company's strength bundled, but the many scattered holdings were formed into a perfect industrial unit. This eventually led to the construction of the Union Railway - a masterly plan; because this connected the widely spaced plants in western Pennsylvania. With iron ore now the only raw material supplied by contractors, Frick devoted his full attention to the matter. The Carnegie Company secured half of the Oliver Mining Company through Frick's initiative and speed . Thus they received a supply of high grade Bessemer ore for their works through a comparatively trivial arrangement of a $ 500,000 loan secured by mortgages on the land. To ensure a continuous supply of iron ore, Frick - with a Pittsburgh industrialist as a partner - bought extensive ore deposits in the recently developed Mesabi Range near Lake Superior. At Frick's urging, Carnegie also leased land in an area owned by John D. Rockefeller .

The Johnstown Flooding

Frick was the leading investor in a group that bought land on Lake Conemaugh, which was also a retention basin, near Johnstown, Pa, and turned the beach there into a private getaway for the wealthy. They called it the South Fort Fishing and Hunting Club. Among the many changes in the area, Frick's group lowered the dam and raised the water level in the lake while not caring about maintenance of the dam, factors that certainly contributed to the dam's collapse on May 31, 1899 and caused the infamous "Johnstown Flood". About 20 million tons of water and countless other tons of rubble and dirt poured into the valley, where around 2,200 people were killed. The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club was charged, but according to the court ruling, the dam breach fell under "force majeure". Frick, whose fortune was estimated at $ 12 million, donated thousands of dollars to the relief fund.

Homestead strike

In 1882 Frick unilaterally reduced wages by more than 20% and refused to negotiate with representatives of the union (Amalgamated Iron and Steel Workers Union). This triggered one of the largest strikes in American history: the Homestead strike . Carnegie had given Frick carte blanche ("they'll give in") and left for his annual vacation in Scotland. With this backing, Frick tried to brutally enforce the “master of the house” position on the part of the entrepreneurs. In order to break the strike in his steel mill, Frick hired not only scabs, but also hundreds of armed groups from the Pinkerton Agency to protect them . In the course of the clashes between strikers and scabs, ten people were killed and sixty wounded in one day before the governor of Pennsylvania declared martial law.

On July 23, 1892, the Russian immigrant and anarchist Alexander Berkman tried to shoot Frick. After breaking into Frick's office, Berkman shot him three times and stabbed him twice with a poisoned knife, but unsuccessfully. Berkman was sentenced to 22 years imprisonment for attempted murder as a result of which he spent 14 years in prison, many of which were in solitary confinement.

The falling out with Carnegie

Although the company was highly successful, the partnership between Frick and Carnegie ended in 1899 after a falling out. When Carnegie, believing he was acting on a binding agreement from 1887, set a price for the coke from the Frick Coke Company that was well below market value, Frick ceased deliveries of coke, which would force the Carnegie Company to close. As the majority owner of the shares in both the coke and steel companies, he forced Frick to resign from both companies. Under the terms of the "watertight" partnership agreement of 1887, the Carnegie Company was obliged to buy Frick's shares upon his resignation. However, Carnegie refused to pay more than the agreed amount, even though in 1899 the value of the shares had increased more than three times. Frick sued for the market value and the invalidity of the agreement. Because Frick's fear of damaging revelations about the apparently huge profits of the Carnegie company, the counterparties settled out of court with a value of $ 15 million of Frick's share. Both men withdrew from management and never spoke to each other again. Frick's successor was Charles M. Schwab as chairman of Carnegie Steel. When Carnegie later tried again to reconcile, Frick replied: "I will see him in hell, where we are both going". (I'll meet him in Hell, where we will both go.)

Portfolio.com put Frick on the list of the worst American directors. Among his critics, he was also known as "America's Most Hated Man".

New interests

In the early 1900s, Frick expanded his interests and built a large coke and steel mill in Clairton , Pa., The St. Clair Steel Company. At the same time, Frick invested in mining companies in West Virginia , Colorado , Wyoming, and central Peru.

He also invested in real estate in Pittsburgh. He financed the construction of the office building, the Frick Building in Pittsburgh, 1901-02 according to the plans of the architects Daniel Burnham, the Frick extension, the William Penn Hotel and the Union Arcades.

The move to New York

In 1904 he had the architects Little & Browne build his summer residence Eagle Rock in Prides Crossing in Beverly, Massachusetts, on the fashionable North Beach in Boston with 104 rooms. He needed the rooms for his paintings that he had packed and they accompanied him to his summer residence. The building was demolished in 1969.

By 1905, Frick's business interests and social obligations had shifted from Pittsburgh to New York City, so he moved to New York with his wife Adelaide and two children, Childs and Helen Clay. He rented William H. Vanderbilt's mansion at 640 Fifth Avenue, where they lived for 9 years. In 1906, Frick began making plans to build his own house in New York by buying land on 70th Street and 5th Avenue. At the time, however, the Lenox Library was still there and Frick had to wait until the New York Public Library opened in 1911, which then housed the Lenox Library . Although Frick had offered to move the Lenox library to another location at his own expense, no agreement could be reached with the city. When he received the title deed for the property in 1912, the building was demolished. After the planning for the house was finished in 1912, construction could begin in 1913.

Here he spent his twilight years in the midst of his art collection, today's Frick Collection - the manufacturer's important art collection that was transferred to a foundation.

Frick bought the Clayton country estate on Long Island , east of New York City , for his son Childs Frick .

Titanic

Frick had booked a suite on the Titanic in February 1912 and wanted to experience her maiden voyage with his wife. But that never happened because his wife sprained her ankle on a Mediterranean cruise and Frick was forced to cancel the trip.

family

Frick married Adelaide Howard Childs on December 15, 1881, (1858-1931) the daughter of Asa Child and Martha Howard Childs. The couple bought a house (Clayton) on the corner of Penn and Homewood Streets in Pittsburgh's posh East End. Those families who lived in the East End of Pittsburgh around 1900 were the country's greatest capitalists and owned 40% of the wealth, ie Heinz, Westinghouse, Carnegie, and Frick. The mail was delivered 7 times a day so they could keep in touch with their factories, banks and the market. Many politicians and presidents came to visit and some business was prepared in these houses. They also had their own private Pennsylvania Railroad station, with a daily express train to New York's financial district.

They had four children, only 2 of whom reached adulthood:

- Childs Frick, born March 12, 1883, died May 9, 1965 in Clayton (Nassau County)

- Martha Howard Frick born August 9, 1885, † July 25, 1891 after a long illness

- Helen Clay Frick was born on September 3, 1888, died on November 9, 1984 in "Clayton", Pittsburgh

- Henry Clay Frick Jr. born July 8, 1892 † August 3, 1892 (premature birth)

further reading

- George Harvey: HENRY CLAY FRICK THE MAN Publisher CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS Published 1928

- James Howard Bridge: The Carnegie millions and the men who made them: being the inside history of the Carnegie Steel Company . With illustrations. Publisher: Limpus, Baker & Co., London, 1903

- Henry C. Frick in: Men who are making America by Berty C. Forbes. Publisher: Forbes Publishing Co, New York, BC, 1917

- Paul Krause: The Battle For Homestead, 1880-1892: Politics, Culture, and Steel . (Pittsburgh Series in Social & Labor History) Publisher: University of Pittsburgh Press; 1992. ISBN 978-0-8229-5466-8

- Kenneth Warren: Triumphant Capitalism: Henry Clay Frick and the Industrial Transformation of America . Publisher: University of Pittsburgh Press; 1996. ISBN 978-0-8229-3889-7

- Martha Frick Symington Sanger: Henry Clay Frick: An Intimate Portrait . Published by Abbeville Press 1998. ISBN 978-0-7892-0500-1

- Les Standiford: Meet You in Hell: Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and the Bitter Partnership That Changed America . Publisher: Broadway, 2006. ISBN 978-1-4000-4768-0

- Quentin R. Skrabec: Henry Clay Frick: The Life of the Perfect Capitalist . Publisher: McFarland 2010 ISBN 978-0-7864-4383-3

Web links

- The Frick Collection - The Frick Art Museum in the former villa of Henry Clay Frick

- Henry Clay Frick: "Builder and Individualist" is an article from The North American Review, Volume 211, Published February 1, 1920

- Henry Clay Frick Bio by John Simkin in Spartacus Educational

- "In Memoriam: Henry Clay Frick Died December 2, 1919, Trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art from October 18, 1909, until the Time of His Death" is an article from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Volume 15. Published February 1 , 1920

- Title: Henry Clay Frick Business Records at he University of Pittsburgh Libraries

Individual evidence

- ↑ Thomas Mellon

- ^ Duquesne Steel Works

- ^ About the Oliver Mining Company

- ↑ South Fork Fishing & Hunting Club ( Memento of the original from November 4, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ 1889 The Johnstown Flood - This Day in History

- ↑ coverage of the New York Times

- ↑ List of the Club members ( Memento of the original from May 9, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ James Howard Bridge: Chapter XX: Carnegie's attempt to depose Frick

- ↑ Appendix - The Equity Suit - Some Extracts from the pleadings of Mr. Henry C. Frick

- ^ Henry Clay Frick Biography in NNDB

- ^ Portfolio's Worst American CEOs of All Time. In: CNBC . April 30, 2009.

- ^ Pictures of Clairton in the Early Days

- ^ Omni William Penn Hotel

- ^ Union Arcade Building Photographs, 1915–1916 - Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh

- ↑ Frick in Pittsburg - Timeline

- ^ The Lenox Library: The Library as Museum

- ^ One East 70th Street Papers. The Frick Collection / Frick Art Reference Library Archives.

- ↑ Eaton, John P., Haas, Charles A., Müller, Torsten ,: Titanic, triumph and tragedy: a chronicle in texts and pictures . Heyne, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-453-12890-7 , pp. 71 .

- ↑ Clayton album, Photos by Clay Frick, circa 1900 ( Memento of the original from April 27, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. There are 36 items in this collection

- ↑ Quentin R. Škrabec: The World's Richest Neighborhood: How Pittsburgh's East Enders Forged American Industry . Publisher: Algora Publishing 2010 ISBN 978-0-87586-795-3

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Frick, Henry Clay |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American industrialist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 19, 1849 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | West Overton , Pennsylvania |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 2, 1919 |

| Place of death | New York City |