Hernando Pizarro

Hernando Pizarro (* 1502 or 1504 in Trujillo , Extremadura ; † 1578 ) was a Spanish conquistador and one of the Pizarro brothers who subjugated and ruled the Inca Empire as the governorate of New Castile .

Life

Unlike his half-brothers Francisco , Gonzalo and Juan Pizarro , Hernando was born as the only legitimate (legitimate) son of Hidalgo , Majorate Lord and infantry captain Gonzalo Pizarro and gained influence at the Spanish court. In 1530, Hernando joined his half-brother Francisco, who had led two expeditions south of Panama along the coast and brought the first news about the rich country of Peru to Spain. Together with him and his half-brothers Gonzalo and Juan, he set off for the New World.

Beginning conflict with Diego de Almagro

Francisco Pizarro had negotiated terms in Spain with Emperor Charles V in a contract (Capitulación of Toledo) , by which his partner Diego de Almagro felt disadvantaged: Almagro was not appointed Adelantado with equal rights , but only Governor of Tumbes , while Francisco Pizarro was promoted to Capitán general (Spanish = captain general ) and governor for life. Hernando Pizarro exacerbated this incipient conflict by arrogant intervention in favor of his half-brother. The chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo , a friend of Almagro's, describes Hernando as follows: “The only legitimate one of them was Hernando Pizarro; you could tell that in his particular arrogance; he was tall and strong, his tongue and lips thick, his nose red and fleshy. He sowed discord everywhere, especially between the two old partners Francisco and Diego de Almagro. "

Hernando Pizarro and Atahualpa

When Francisco Pizarro set off from Panama on his third expedition south, his brothers accompanied him. Together with Hernando de Soto , Hernando Pizarro personally brought the Sapa Inca Atahualpa in his army camp with his brother's invitation, which initiated Atahualpa's later capture.

After Atahualpa was captured in the Battle of Cajamarca , he offered a large gold and silver ransom to regain his freedom. For this purpose he sent messengers into the country who should bring the gold. Hernando rode with 20 men for three months through unexplored land to Pachacámac 600 km south and supervised the looting of the sun temple and the bringing of the gold. He first described the existence of double bridges over a ravine close to each other on his way from the coast over the stepped Inca road to Piga on the way inland: While one served the common people in exchange for a bridge toll , the second was reserved for the nobility. On the way back via Jauja he succeeded in persuading the dreaded General Chalcuchímac to return with him to Cajamarca. So the general fell into the hands of the Spaniards.

When most of the ransom had arrived, the Spaniards were still at odds over what to do with Atahualpa. Almagro urged to get rid of him, while Hernando Pizarro was one of his greatest advocates.

Hernando's use at court

In 1533 Francisco sent him back to Spain to accompany the crown portion of the gold and silver loot, because Hernando had the best relations at court and was supposed to represent Pizarro's interests against Francisco's difficult partner Almagro. At the same time, Francisco Pizarro probably saw this as a welcome opportunity to temporarily remove from the South American stage the brother that was constantly sowing conflict between himself and Almagro due to his arrogance. After Hernando's departure, Almagro and Francisco Pizarro had Atahualpa killed after a show trial.

At the Spanish court, Hernando Pizarro reached a royal capitulación , in which Almagro was granted its own " Neutoledo " zone , which was supposed to border the southern border of the Francisco Pizarros governorate, but which at the same time expanded his brother's governorate by 70 miles to the south. This Capitulación already harbored the seeds of new conflicts between Almagro and Francisco Pizarro, because it was unclear whether the Inca capital of Cusco Pizarro Castilla La Mancha would include or Almagros Neutoledo.

Dominion over Cusco

In Cusco, Francisco Pizarro had installed Manco Cápac as the new Sapa Inka. Treated with respect at first, Manco increasingly became the powerless tool of the Spaniards and was effectively under house arrest . When Francisco Pizarro left the Inca capital to devote himself to founding the city of Ciudad de los Reyes ("City of Kings", today's Lima) and other cities, he left Cusco under the command of his brothers Gonzalo and Juan. These abused Manco, who tried to escape in vain, and put him in chains. When Hernando came from Spain, he ended the abuse but couldn't prevent Manco from escaping on some pretext and starting a general uprising.

Cusco, Lima and other places inhabited by the Spaniards were besieged with huge armies for several months, communication between Cusco and Lima was cut off and in the course of the dramatic siege Cusco was almost completely destroyed. Hernando Pizarro undertook defenses and military punitive expeditions. In January 1536 he advanced with a contingent of around 100 Spaniards and other indigenous warriors through the "Valle Sagrado" (Spanish = sacred valley) to the Inca fortification of Ollantaytambo , where Manco resided. As the Spanish approached the fortress at dawn, they saw countless determined indigenous warriors. They threw bulging sacks at the Spaniards with the severed and withered heads of their Spanish brothers in arms. Among other things, the Inca warriors had diverted the Río Patacancha through canals and dammed it. When approaching, the Incas flooded the plain, so that the Spaniards had to retreat to Cusco again.

The climax of the rivalry with Diego de Almagro

After returning from his fruitless expedition through the Atacama Desert to northern Chile in April 1537, Diego de Almagro learned that Hernando Pizarro and his brothers were in power in Cusco and had been under dangerous siege by Manco Cápac for almost a year. Francisco Pizarro was in Lima with a small troop with which he could only defend himself and the newly founded city, but could not contribute anything to the relief of Cusco. Since Almagro, in his own opinion, had not received an adequate reward as Francisco Pizarro's most important partner in the conquest of Peru, he then claimed the dignity of his governorship and his new title as governor of Chile Cusco as part of his booty. Almagro captured Hernando and Gonzalo Pizarro, but defended their lives when his people wanted to kill them. Francisco later obtained Hernando's release, promising that Hernando would return to Spain until the king had resolved the issues at stake. Hernando did not stick to this agreement.

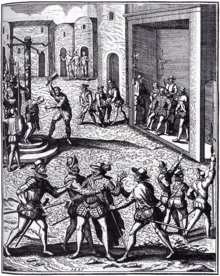

In April 1538, Hernando returned with Gonzalo Pizarro at the head of an army to face Almagro. In the ensuing battle of Las Salinas , the Pizarro brothers achieved a decisive victory in which they occupied the city and arrested Almagro. Oviedo reports that during the night Hernando Pizarro faked a liberation action by Almagros party members, for which Hernando Pizarro sentenced Almagro to death without due process on the basis of summary accusations. Almagro is said to have demanded an orderly process, as it is due to him as the governor of the Spanish king, which Hernando Pizarro adamantly refused and which is said to have ordered Almagro to be strangled in the morning hours of July 8, 1538. Oviedo's descriptions should be viewed with caution, as he was not only a friend of Almagro's, but never resided in Cusco, but in Panama and later in Santo Domingo . On the other hand, he knew all the people involved personally, had access to all documents and will certainly have been very well informed about the circumstances of Almagro's death.

Return to Spain

The killing of Almagro and the general disorder that emanated from the power struggles between the Spaniards caused great unrest at the Spanish court. Again the choice fell on Hernando, who should let his contacts play at the Spanish court: in 1539 he returned to Spain to represent the interests of the Pizarros.

The Spanish Crown appointed the licentiate Cristóbal Vaca de Castro as President of the Real Audiencia of Panama, the court that at that time had jurisdiction over all of Spanish America in order to achieve peace between the parties. Vaca de Castro persecuted Almagros' mestizo son, Diego "el Mozo" , who led the anti-Pizarro conquistadors and was instrumental in the murder of Francisco Pizarro on June 26, 1541. The young Almagro and his father's supporters understood their murder and the subsequent looting as revenge for the murder of old Diego de Almagro. Vaca de Castro succeeded in September 1542 in defeating Diego Almagro and "those from Chile", which gave Hernando Pizarro and his brothers a temporary boost, as the encomiendas of the defeated mutineers were redistributed in favor of those involved in the suppression of the mutiny.

But the suspicion of having brought about the execution of Almagros and committed treason was too great: Despite bribery, Hernando was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1539. From 1540 he disappeared in the La Mota castle near Medina del Campo , where he remained imprisoned until May 17, 1561 (according to other sources 1569). Sentenced to be exiled to Africa in 1545 , the sentence was commuted to imprisonment. Thanks to his enormous fortune, Hernando managed to live with Isabela del Mercado in custody and to father their daughter Francisca Pizarro y Mercado. In 1552, Hernando Pizarro rejected his aristocratic lover to marry his niece Doña Francisca Pizarro Yupanqui , the illegitimate daughter of his brother Francisco and the Inca Princess Inés Huaylas Yupanqui . His wife shared a prison with him for nine years. Together they had five children, three of whom survived childhood. After being sentenced to a fine, he was later pardoned , disappeared from the public eye and returned to Trujillo in Extremadura, where he built a large palace in the local Plaza Mayor.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Liselotte and Theodor Engl: Pleasure in history - The conquest of Peru. Munich 1991, ISBN 3-492-11318-4 , p. 442

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Behringer: Pleasure in history - America - The discovery and creation of a new world. Munich 1992, ISBN 3-492-10472-X , p. 457

- ↑ a b dtv Brockhaus Lexicon. Munich 1986, Volume 14, ISBN 3-423-03314-2 , p. 158

- ^ FA Kirkpatrick: The Spanish conquistadors. Goldmann's Yellow Pocket Books 859, Munich, p. 120

- ↑ Liselotte and Theodor Engl: Pleasure in history - The conquest of Peru. Munich 1991, ISBN 3-492-11318-4 , p. 72

- ↑ Max Zeuske: The Conquista. Leipzig 1992, ISBN 3-361-00369-5 , p. 106

- ↑ Victor W. von Hagen: Sun Kingdoms. Munich 1962, ISBN 3-426-00125-X , p. 310

- ↑ Max Zeuske: The Conquista. Leipzig 1992, ISBN 3-361-00369-5 , p. 107

- ^ FA Kirkpatrick: The Spanish conquistadors. Goldmann's Yellow Pocket Books 859, Munich, p. 128

- ↑ Liselotte and Theodor Engl: Pleasure in history - The conquest of Peru. Munich 1991, ISBN 3-492-11318-4 , p. 188

- ↑ Gottfried Kirchner: Terra X - Riddles of Old World Cultures - New Series. Heyne-Taschenbuch, Frankfurt / Main 1986, ISBN 3-453-00738-7 , p. 152

- ↑ Liselotte and Theodor Engl: Pleasure in history - The conquest of Peru. Munich 1991, ISBN 3-492-11318-4 , p. 212f

- ↑ Gottfried Kirchner: Terra X - Eldorado, search for the gold treasure. Munich 1988, ISBN 3-453-02494-X , p. 43

- ^ Franz Kurowski : Spain - Rise and Fall of a World Empire. Verlagsgesellschaft Berg , Berg am See 1991, ISBN 3-921655-76-5 , p. 175

- ↑ a b Max Zeuske: The Conquista. Leipzig 1992, ISBN 3-361-00369-5 , p. 114

- ^ Franz Kurowski: Spain - Rise and Fall of a World Empire. Verlagsgesellschaft Berg, Berg am See 1991, ISBN 3-921655-76-5 , p. 177

- ^ FA Kirkpatrick: The Spanish conquistadors. Goldmann's Yellow Pocket Books 859, Munich, p. 149

- ↑ Michael Gregor: The blood of the sun god. In: Hans-Christian Huf (Ed.): Spinx 6 - Secrets of the history of Spartacus to Napoleon. Munich 2002, ISBN 3-453-86148-5 , p. 153

- ^ FA Kirkpatrick: The Spanish conquistadors. Goldmann's Yellow Pocket Books 859, Munich, p. 159

- ↑ Peter Bigorajski: The Conquest of Peru # Hernando Pizarro's fate. Retrieved August 17, 2004 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pizarro, Hernando |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Spanish conquistador |

| DATE OF BIRTH | before 1475 or 1478 or 1502 or 1504 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Trujillo , Extremadura , Kingdom of Castile |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1557 or 1578 |