Hurdia

| Hurdia | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

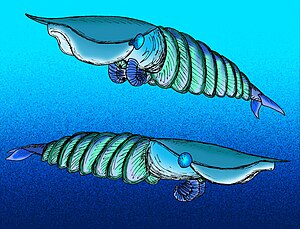

Artistic reconstruction of Hurdia Victoria |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Middle Cambrian | ||||||||||||

| 505 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Hurdia | ||||||||||||

| Walcott , 1912 | ||||||||||||

| species | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Hurdia refers to an extinct genus of the Anomalocarididae from the middle Cambrian 505 million years ago. The type species Hurdia victoria is currently the only valid way of genus and was in 1912 by Charles D. Walcott from a single carapace from the Burgess Shale firstdescribed . Walcott assumed at the time, however, that the fossil described was part of the body of an unknown arthropod . The name Hurdia refers to Mount Hurd , which is located near the site.

Only Daley et alii were able to assign Hurdia to the anomalocaridids on the basis of new material in 2009.

Discovery history and classification

Like other anomalocaridids, Hurdia has a complex history of discovery. The mouthparts and limbs and body and Kopfcarapax were all described as their own style with different systematic allocation. For example, the front appendages were interpreted by Walcott himself as the grasping tools of Sidneyia , a Cambrian arthropod . Similar to the case of other anomalocaridids, the mouth opening of Hurdia was initially classified as a jellyfish species Peytoia nathorsti - also by Walcott. Other finds were believed to be fossil remains from representatives of the Holothuroidea.

When Briggs and Whittington found out in the 1980s that countless of these taxa were based on parts of the same animal, they created two genera of the anomalocaridids, Anomalocaris and Laggania . Hurdia fossils were assigned to either one or the other genus, which had stalk eyes, a disk-shaped mouth opening equipped with two movable claws and a lamellar segmented body with a series of lobe-like appendages for locomotion.

In the 1990s, Desmond Collins from the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto was able to connect the fossils and discovered a third anomalocaridid in this way. Collins' discovery led to a re-examination of the known material. It could be established that the carapace Hurdia , which was previously ascribed to a crustacean, as well as another carapace, which was ascribed to the phyllopod arthropod Proboscicaris in the sixties, actually belonged to a new genus of anomalocaridids. The remains of Hurdia , which were distributed over at least eight Cambrian taxa , were identified on the basis of new material and a renewed review of older collections . This discovery shed light on the systematics and the complex morphology of the Cambrian Anomalocaridids by showing that previous reconstructions of Anomalocaris and Laggania were partly based on Hurdia fossils and were therefore flawed.

description

Some specimens of Hurdia could grow up to 8 inches long. The carapace took up about half the length of the body. Two short, fused stalks with oval eyes protruded from the rear notches of the anterior carapace. The mouthparts of Hurdia consisted of 32 plates arranged in a ring, which were covered with two to three small teeth. Four larger plates were arranged perpendicular to each other and separated by seven smaller plates. The outer edges of these plates were bent downwards and gave the mouth opening a curved shape. Within the rectangular, central opening of the mouth there were five rows of teeth lying on top of each other like roof tiles, each with eleven thorns.

The front thorny claws consisted either of eleven robust segments with a back ( dorsal ), three lateral ( lateral ) and five elongated ventral ( ventral ) thorns or they had nine thinner segments, which were occupied with a dorsal and seven ventral thorns. Both types of appendages can be unequivocally associated with fossils of Hurdia , so that it can be assumed that either two types of Hurdia existed or that one type has been passed down with two morphs .

The hull of Hurdia consisted of seven to nine poorly defined segments of roughly the same size. Each of the segments was laterally set with a pair of lobes , which were covered by a smooth cuticle . Above that lay lance-shaped structures that were arranged in rows and, due to their morphology and arrangement , are interpreted as gills . These lance-shaped structures were attached to the front ends of the lobes and hung freely behind. Four pairs of smaller lance-shaped structures were arranged around the mouth and front claws.

Paleoecology

Hurdia is the most common anomalocaridid, at least in the Walcott Quarry, and occurs in another five locations in the Canadian Rocky Mountains . Other finds come from the Wheeler Formation in Utah , and fossils are also known from Bohemia , the People's Republic of China and possibly Nevada . This suggests that Hurdia was widespread worldwide and, as a generalist, was able to successfully adapt to various environmental conditions.

The carapace on the head is unique in terms of its composition and its position at the front of the head of the animal. No other living or fossil arthropod has such a complex anterior structure. The position of the carapace in the fossil record is probably original and not the result of a shift or deformation that only occurred after the specimen died.

Like other anomalocaridids, Hurdia was most likely a nectic predator or scavenger who used the side lobes to swim through the water in search of prey. The large eyes, the tooth-reinforced mouth opening and the claws suggest that Hurdia was actively looking for prey. The less robust structure of the grasping tools compared to Anomalocaris suggests that Hurdia may have hunted different prey than the larger Anomalocaris.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g Daley, C .; Budd, E .; Caron, B .; Edgecombe, D .; Collins, D .; Graham E. Budd, 1 Jean-Bernard Caron, 2 Gregory D. Edgecombe, 3 Desmond Collins (Mar 2009). "The Burgess Shale Anomalocaridid Hurdia and its Significance for Early Euarthropod Evolution". Science 323 (5921): 1597-1600. doi : 10.1126 / science.1169514

- ↑ Desmond Collins: The "evolution" of Anomalocaris and its classification in the arthropod class Dinocarida (nov.) And order Radiodonta (nov.). Journal of Paleontology March 1996, v. 70, p. 280-293

- ^ HB Whittington and DEG Briggs: "The Largest Cambrian Animal, Anomalocaris, Burgess Shale, British Columbia". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 14 May 1985 vol. 309 no. 1141 569-609 doi : 10.1098 / rstb.1985.0096

- ↑ Briggs, DEG, Lieberman, BS, Hendrick, JR, Halgedahl, SL and Jarrard, RD (2008): "Middle Cambrian arthropods from Utah". in: Journal of Paleontology , 82: 238-254.

- ↑ Chlupáč, I. and Kordule, V. (2002): "Arthropods of Burgess Shale type from the Middle Cambrian of Bohemia (Czech Republic)". in: Bulletin of the Czech Geological Survey , 77: 167-182.

Web links

Hurdia victoria in the Virtual Museum of Canada. 2011