Inclusive and exclusive we

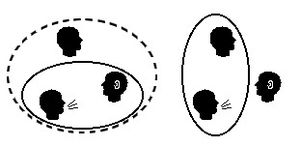

Inclusive we and exclusive we form a grammatical subdivision of the majority of the 1st person in many languages of the world . A distinction is made here as to whether the person addressed (addressee) is included or excluded. The inclusive we is a pronoun that denotes the speaker, the addressed and possibly third persons. In contrast, the exclusive we excludes the addressed, but includes third persons. In most European languages there is only one pronoun for a group that includes the speaker. There is no distinction between whether the person addressed is included.

function

In German you can say: 'We both go to the cinema.' If no third person is present, it is clear that only the speaker ( 1 ) and the addressee ( 2 ) are meant and possible third persons ( 3 ) are excluded. If, however, a third person is present, the addressee is not addressed directly by "both of us", but the speaker means "himself and the third person, but not the addressee": 'Both of us (my colleague and I) go into the Movie theater; are you coming with?'.

Many languages have a dual we (grammatically abbreviated as 1 + 2 ) that expresses the function of 'both of us'. In addition, there is also a majority of this 'inclusive we' ( 1 + 2 + 3 + ... ) in many languages . This form then designates a group, which always includes the speaker ( 1 ) and the addressee ( 2 ), but also any number of third parties.

This results in the following scheme:

| Singular | dual | Plural | |

| 1st person (excl.) | 1 | 1 + 3 | 1 + 3 + 3 + 3 +… |

| 1 + 2 (incl.) | 1 + 2 | 1 + 2 + 3 + 3 +… | |

| 2nd person | 2 | 2 + 2 | 2 + 2 + 2 + 2 +… |

| 3rd person | 3 | 3 + 3 | 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 +… |

The cell of 1 + 2 and singular cannot logically be filled, since an inclusive pronoun always refers to at least two people (namely: 'I and you').

An example from Walmajarri spoken in Northwest Australia:

| Singular | dual | Plural | |

| 1st person (excl.) | ngayu (me) | ngayarra (me + he / she) | nganimpa (me + he / she + he / she + ...) |

| 1 + 2 (incl.) | ngaliyarra (me + you) | ngalimpa (me + you + he / she + he / she + ...) | |

| 2nd person | nyuntu (you) | nyurrayarra (you + you) | nyurrawrachti (you + you + you + ...) |

| 3rd person | nyantu (he / she) | nyantuyarra (he / she + he / she) | nyantuwarnti (he / she + he / she + he / she + ...) |

distribution

According to a study by Balthasar Bickel and Johanna Nichols (2005), the distinction between inclusive and exclusive we has been proven in 40 percent of the world's languages. Although this semantic distinction is found in languages on every continent, Bickel and Nichols note that it is most clearly found in the area of the Pacific Ring. As the Pacific Ring, they refer to Southeast Asia , Oceania and the Pacific coast of North and South America . However, inclusive pronouns are most common in the Australian and South American languages . Bickel and Nichols attribute this distribution to prehistoric migrations .

Examples

Chinese

In standard Chinese , zánmen咱们 [ ʦánmən ] always refers to all people present (inclusive). The pronoun wǒmen我们 [ wòmən ], on the other hand, refers either only to a group of people to which the speaker also belongs (exclusive), or also to all present (inclusive); wǒmen我们 is therefore ambiguous.

Malay

In Malay , the pronoun kita is inclusive and kami is exclusive. You could say: “We (kami - excl.) Go shopping, then we eat (kita - incl.). “That would make it clear that the guest does not come along to go shopping, but is invited to eat. An ambiguity as to whether the guest is included or not, as in European languages, is not possible.

Tagalog

As an Austronesian language , the Tagalog has both the inclusive pronoun tāyō ( Bay .: ᜆᜌᜓ ) and the exclusive kamì ( Bay .: ᜃᜋᜒ ). The associated possessive pronouns are nāmin ( Bay .: ᜈᜋᜒ ) and nātin ( Bay .: ᜈᜆᜒ ). A singulares We , as in Indo or Sino-Tibetan languages is the case, there is not.

Quechua

Quechua , an indigenous language or group of closely related languages in South America with over 10 million speakers, knows the inclusive and exclusive we both in all forms of the verb and in the possessive suffixes as well as in the personal pronoun. So it says:

- ñuqanchik : we ( and you too , stressed) - plural inclusive

- ñuqayku : we ( but not you , stressed) - plural exclusive

- rinchik : we're going ( and so are you ) - plural inclusive

- riyku (or riniku ): we go ( but you don't ) - plural exclusive

- allqunchik : our dog ( and yours too ) - plural inclusive

- allquyku : our dog ( but not yours ) - plural exclusive

Cherokee

Cherokee , an Iroquois language that today has around 20,000 speakers, mainly in Oklahoma and North Carolina , consistently differentiates between the two forms of we, also in the verb. Since it also knows a dual (two number), the German words we go correspond to four forms:

- inega : we both go ( you and me ) - dual inclusive

- osdega : we both go ( but you don't ) - dual exclusive

- idega : we ( 3 and more ) go ( and you too ) - plural inclusive

- otsega : we ( 3 and more ) go ( but you don't ) - plural exclusive

The persons are indicated in this language by prefixes .

Tamil

Even the Tamil , the main language of southern India, knows an inclusive ( NAM ) and an exclusive ( nāṅkaḷ ) We. However, this is not reflected in the personal endings, although Tamil otherwise has different endings for the people.

Therefore one says nāṉ ceykiṟēṉ for "I do", nī ceykiṟāy for "you do", but: nām ceykiṟōm for "we do (and you also take part)" and nāṅkaḷ ceykiṟōm for "we do (and you do not participate)" .

Different types

A distinction is absolute of relative Numerussystemen . The above scheme works with absolute number categories ; That is, all forms in the 'Dual' column always speak of 2 people. There are also languages that have a trial form in addition to the dual (e.g. Wunambal, which is spoken on the coast of Northwest Australia). All forms in the Trial column then speak of three people in each case. However, there are also systems of pronouns that determine their number categories relatively. Here the number of people addressed is determined relative to the minimum group of the respective person category (1st, 1 + 2nd, 2nd or 3rd person).

A schematic example of a relative number system:

| Minimal | Unit-augmented | Augmented | |

| 1st person (excl.) | 1 | 1 + 3 | 1 + 3 + 3 + 3 +… |

| 1 + 2 (incl.) | 1 + 2 | 1 + 2 + 3 | 1 + 2 + 3 + 3 +… |

| 2nd person | 2 | 2 + 2 | 2 + 2 + 2 + 2 +… |

| 3rd person | 3 | 3 + 3 | 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 +… |

In contrast to the absolute system (the scheme under function ), the first cell in the relative system can be filled for the inclusive person (1 + 2), namely with the minimal group of the inclusive person, i.e. 'me and you'. The terms singular, dual and plural are replaced with minimal ('smallest group'), unit-augmented ('extended by 1') and augmented ('extended by 1 + X'). That seems illogical and unclear at first. However, the following two tables show how to incorrectly analyze a relative system language (first table) and how to correctly analyze it (second table). The language here is Ngandi . It is spoken in the southwestern Arnhem Land in northern Australia.

| Singular | dual | Trial | Plural | |

| 1st person (excl.) | ngaya | nyowo- rni | nye- rr | |

| 1 + 2 (incl.) | nyaka | ngorrko- rni | ngorrko- rr | |

| 2nd person | nugan | nuka- rni | nuka- rr | |

| 3rd person | niwan | bowo- rni | ba-wan |

It is clear here that the analysis is misleading. On the one hand, the number category Trial is only relevant for the inclusive person and not for the 1st, 2nd and 3rd person. On the other hand, the endings indicate where the forms actually belong. The ending -rni therefore clearly refers to the number category dual, although in the inclusive person this ending means three people. This means that -rni says: "increase by 1". So in the 1st person, 2nd person and 3rd person 2 people are meant. In the inclusive person, this 'increase of 1' leads to 3 people. That is why a relative number system makes sense.

| Minimal | Unit-augmented | Augmented | |

| 1st person (excl.) | ngaya | nyowo- rni | nye- rr |

| 1 + 2 (incl.) | nyaka | ngorrko- rni | ngorrko- rr |

| 2nd person | nugan | nuka- rni | nuka- rr |

| 3rd person | niwan | bowo- rni | ba-wan |

It can be seen from the second analysis that the inclusive person category is treated in a relative numbering system in the same way as the 1st person, 2nd person and 3rd person. So the smallest group of the inclusive person (me and you) is treated like a singular in the other persons.

literature

- Balthasar Bickel , Johanna Nichols: Inclusive-exclusive as person vs. number categories worldwide . In: Elena Filimonova: Clusivity. Typological and case studies of the inclusive-exclusive distinction. John Benjamin Publishing, Amsterdam 2005, ISBN 90-272-2974-0 .

- Elena Filimonova: Clusivity. Typological and case studies of the inclusive-exclusive distinction. John Benjamin Publishing, Amsterdam 2005, ISBN 90-272-2974-0 .

- Michael Cysouw: The Paradigmatic Structure of Person Marking . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2003, ISBN 0-19-925412-5 .

Ngandi's examples come from:

- Heath Jeffrey: Ngandi grammar, texts and dictionary. Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra 1978.

Web links

- Anatol Stefanowitsch: Pluralis Avaritiae . in the Bremer Sprachblog and We are We .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Snježana Kordić : Personal and reflexive pronouns as carriers of personality . In: Helmut Jachnow , Nina Mečkovskaja, Boris Norman, Bronislav Plotnikov (eds.): Personality and Person (= Slavic study books ). nF, Vol. 9. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-447-04141-2 , p. 146 ( irb.hr [PDF; 2.8 MB ; accessed on April 6, 2013]).

- ↑ Joyce Hudson: The core of Walmatjari grammar. Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Humanities Press, New Jersey 1978, ISBN 0-85575-083-9 .

- ^ Gregor Kneussel: Grammar of Modern Chinese. 2nd Edition. Foreign Language Literature Publishing House, Beijing 2007, ISBN 978-7-119-04262-6 , p. 45.

- ↑ Jerry Norman: Chinese. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1988, ISBN 0-521-22809-3 , p. 158.