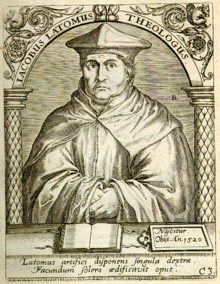

Jacques Masson (theologian)

Jacques Masson or Iacobus Latomus (* around 1475 in Cambron , † May 29, 1544 in Leuven ) was a theologian.

Life

Latomus, as he was almost exclusively called, came from Hainaut . He received his training in the artes liberales at the Collège Montaigu in Paris . In 1500 he obtained the title of Magister and became head of the college for poor students ( Domus Standonica ) in Leuven, newly founded by Johannes Standock ; at the same time he began studying theology at the University of Leuven . Jacques Masson worked in Leuven from 1500 until his death in 1544.

In 1504 his term of office as head of the college ended. Masson lectured at the facultas artium and became a member of the Academic Council of the University of Leuven on November 3, 1510. On August 16, 1519 he received his doctorate in theology. He was then a member of the administrative board of the theological faculty and in 1520, 1526 and 1529 dean of the theological faculty. In 1537 he was rector of the University of Leuven. In 1526 he was named canon by Robert de Croy , Bishop-designate of Cambrai . In addition to Robert de Croy, Charles de Croy was also one of Masson's students. In the meantime he had latinized his name and in 1535 became full professor and beneficiary of the St. Andrew's altar in St. Peter's Church in Löwen .

Occasionally Jacques Masson appeared as theological advisor to the Inquisition , “z. B. in the trials against Jacobus Praepositus (1522) and against William Tyndale (1535–1536) "

theology

Latomus developed the principles of his theology in dealing with the text Ratio verae theologiae by Erasmus of Rotterdam . In contrast to the humanist Erasmus, who relies primarily on philological knowledge in theology , Latomus wants to continue on the scholastic path, which in addition to the study of Holy Scriptures also includes logic, dialectics, moral philosophy and metaphysics. This he explains in 1519 in his work De trium linguarum et studii theologici ratione dialogus .

Latomus then played an important role in the controversy with Martin Luther . In 1521 he published the work Articulorum doctrinae fratris M. Lutheri per theologos Lovanienses damnatorum ratio ex sacris literis et veteribus tractatoribus (hereinafter referred to as " Ratio "), in which he - unlike other controversial theologians of his time - dealt with Luther's indulgence theses in detail and on one A series of " inconvenientiae " (inconsistencies) drew attention. These consist of conclusions through which Luther's theses in the form of a reductio ad absurdum are so exaggerated (without, however, distorting their meaning) that their statement is reversed into the opposite. In the second part of the treatise, Latomus then goes into Luther's evidence of Scripture and authority and shows that the reformer's view differs considerably from church tradition and is sometimes not covered by the biblical passages or quotations from the Father. Here, the literary work arose from a series of lectures that he held with a kind of pastoral goal; namely to protect his students from the Reformation, in which Masson saw a danger to the salvation of the soul, and against which he wanted to give the arguments entrusted to him for refutation.

In the further discussion with Luther, Latomus finally comes to the conclusion that he could not share Luther's understanding of Scripture. Based on Luther's interpretation of the parable of the Good Samaritan ( Lk 10.25-37 EU ), Latomus remarks that Luther's interpretation contradicts that of the church fathers and proves this with a quote from the works of St. Jerome . From this he concludes that Luther disregards the church's tradition of interpretation as a whole and sees himself compelled to make the personal statement:

"This is my belief that I will not give up until I see the reasons to break away from it."

With this, Latomus shows that he can neither follow Luther's method of interpreting scriptures nor his distinction between donum and gratia , which he had developed in the indulgence theses and in their defense. He comes to the conclusion that Luther never really thought or spoke about grace and sin because he recognized the scriptures but the fathers rejected it.

effect

In his essays, Jacques Masson took a stand against two of the most famous scholars of his time, Erasmus of Rotterdam and Martin Luther. While Erasmus left it at a single apology and later did not go into Latomus, Luther, who fled to the Wartburg shortly after the publication of the Ratio , was initially extremely upset. Twelve years later (1533), however, Luther speaks appreciatively of Latomus, who is "the most learned among the opponents", while in 1546, shortly before his death and two years after Latomus' death, he wrote an - unfinished - pamphlet with the title Against the Parisian and Löwen donkeys in which he again attacked Latomus sharply. For Luther, Latomus remained just as present throughout his life as his attitude towards the “Scholast” was ambivalent.

The writings of Jacobus Latomus were largely ignored until the 20th century, and Luther researchers mainly drew their knowledge about them from Luther's replies. An exception is Joachim Rogge , for him Latomus is one of the "very few Roman Catholic theologians who ever scientifically and seriously dealt with Luther" and who were not content with condemning his teaching.

It was not until the beginning of the 21st century that the Johannes a Lasco library in Emden found a previously neglected first print of the “ Ratio ” from 1521, which revived the scientific interest in Jacques Masson.

Works

- De trium linguarum et studii theologici ratione dialogus. (Antwerp 1519)

- Articulorum doctrinae fratris M. Lutheri per theologos Lovanienses damnatorum ratio ex sacris literis et veteribus tractatoribus. (Antwerp 1521)

- De primatus pontificis adversus Lutherum. (1525)

- De confessione secreta. (Antwerp 1525)

- Confutationum adversus Guililmum Tindalum. (1542)

- Duae epistolae, una in libellum de ecclesia, Philippo Melanchthoni adscripta; altera contra orationem factiosorum in comitiis Ratisbonensibus habitam. (Antwerp 1544)

- Opera omnia. (Lions 1550)

literature

- Peter Fabisch, Erwin Iserloh : Latomus, Jacobus . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 20, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1990, ISBN 3-11-012655-9 , pp. 495-499.

- Hannegreth Grundmann: Gratia Christi. The theological justification of the indulgence by Jacobus Latomus in the controversy with Martin Luther. Lit, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-64-311720-5 .

- Heribert Smolinsky : LATOMUS, Jacobus (Jacques Masson, Steinmetz). In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 4, Bautz, Herzberg 1992, ISBN 3-88309-038-7 , Sp. 1219-1221.

- Joseph E. Vercruysse: Jacobus Latomus and Martin Luther. Introductory note to a controversy. In: Gregorianum. Vol. 64 (1983), p. 515 ff.

- Joseph E. Vercruysse: Jacobus Latomus (approx. 1475-1544) . In: Erwin Iserloh (Hrsg.): Catholic theologians of the Reformation period. 2nd Edition. Volume 2, KLK, Münster 1996, pp. 7-26.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Joseph E. Vercruysse: Jacobus Latomus and Martin Luther. Introductory note to a controversy . In: Gregorianum 64, 1983, pp. 516-518

- ^ Joseph E. Vercruysse: Jacobus Latomus (approx. 1475-1544) . In: Erwin Iserloh (Hrsg.): Catholic theologians of the Reformation period . Vol. 2, KLK, Münster 1985, 2nd ed. 1996, pp. 7-26, quotation on p. 10

- ↑ Hannegreth Grundmann: Gratia Christi. The theological justification of the indulgence by Jacobus Latomus in the controversy with Martin Luther. P. 16

- ↑ in the translation by Hannegreth Grundmann: Gratia Christi . P. 116

- ^ Jacobus Latomus: Opera omnia. Löwen 1550, p. 59 r , 60 v

- ↑ "doctissimus adversariorum"; WATR 5, 75, No. 5345

- ↑ WA 54, 444-458

- ↑ Hannegreth Grundmann: Gratia Christi. P. 4

- ↑ Joachim Rogge: Gratia and donum in Luther's writing against Latomus. In: Joachim Rogge, Gottfried Schille (eds.): Theological Trials 2. Berlin 1970, pp. 139–152, quotation p. 139 f.

- ↑ Hannegreth Grundmann: Gratia Christi. P. 6

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Masson, Jacques |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Latomus, Iacobus; Latomus, Jacobus |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | theologian |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1475 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Cambron |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 29, 1544 |

| Place of death | Lions |