Jacobin

The Jacobins were, in a formal sense, the members of a political club during the French Revolution . In terms of content, in France from 1793 the followers of Maximilien de Robespierre were referred to as Jacobins, but also as Robespierrists . They represented the political left and sat down u. a. for the abolition of the monarchy . The Jacobins found their followers to a large extent in urban lower classes , but also among doctors, lawyers and craftsmen. The name Jacobin Club referred to the place of assembly, the Jacobin monastery of Saint-Honoré in Paris.

In a broader sense, the term also refers to those supporters of the revolution inside and outside France who were not members of the Jacobin Club, but who were also members after the execution of King Louis XVI. still advocated the revolution and aspired to a republican form of government.

The Jacobin Club

After the opening of the Estates General by King Louis XVI. on May 5, 1789, political clubs were founded in France and particularly in Paris . When the National Assembly was constituted on June 17, 1789 and three days later it vowed not to part again until it had created a constitution ( Ballhaus Oath ), political camps with different opinions arose from the clubs.

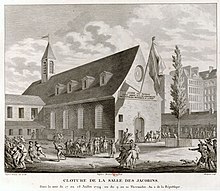

The club was originally founded on April 30, 1789 as a Breton Club . This ceased its activities in August 1789, as no agreement was reached on the king's veto right. Following a suggestion from Sieyès in October, Claude-Christophe Gourdan re-established the club in December of that year under the name Society of Friends of the Constitution . He had found the former library of the Jacobin monastery in Paris as a meeting place.

Differentiation from the other clubs

In the period from 1789 to 1799 one cannot speak of political parties in the current sense. They were more like debating societies and it was quite common to be a member of several clubs. Even the leader of the Girondins, Jacques Pierre Brissot, was also a member of the Jacobins for a long time. These Girondins , however, had a completely different history than the Jacobins and, in contrast to them, were more inclined to a federal state than a central state with Paris as its center.

The Cordeliers , who were also recruited from members of the Breton Club, but had been campaigning for a republic from the very beginning, on April 27, 1790, and were to be settled further to the left than the Jacobins , had more of the same origins . Together, these two clubs formed the so-called Mountain Party , a name derived from the seating arrangements in parliament. This close collaboration on this Montagne ended at the beginning of spring 1794. The Cordeliers, unlike the Jacobins, did not charge a membership fee.

On July 18, 1791, a large part of the previous club split off under the impression of the massacre on the Marsfeld . The new political association named Feuillants after its meeting place continued to advocate a constitutional monarchy and considered the previous revolution to be far-reaching enough. The Feuillants must even be viewed as further to the right than the Gironde.

Goals and developments

Imbued with the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau , they wanted to replace the constitutional monarchy achieved during the French Revolution with a republic . Through leaflets, newspaper articles and engaging speeches, they increasingly influenced the masses and found supporters across the country. Above all the common people, the workers and the petty bourgeoisie, called sans-culottes , were on the side of the Jacobins. These were more firmly organized than other political clubs and maintained a network of branch companies in the provinces, so that they could influence public opinion there through leaflets, newspaper articles and engaging speeches. The French Revolution was a learning process, which is why long-time club members changed their original political opinions. Such was Maximilien Robespierre originally monarchist, was not interested in the social issues. The Jacobins made politics for the common people. Workers and petty bourgeoisie were originally against the war, demanded the sale of national goods - that was the expropriated property of the church and emigrants - in small plots , wanted a unified, centralized France and demanded a planned economy with maximum prices .

Radicalization and temporary end

In 1792, against the will of their moderate opponents, the Girondists, they forced a trial against the king. Under the leadership of Maximilien de Robespierre, from the summer of 1793 they established a regime of terror, the reign of terror (French: La Terreur ), which was mainly characterized by the mass execution of political opponents, the energetic and bloody suppression of counterrevolutionary movements in the provinces and a coercive economy with high prices. In the same summer of 1793, the Jacobins passed a constitution influenced by the ideas of Rousseau , which strengthened direct democracy , adopted a mandatory national goal (“general happiness”) and contained social rights (to work and education). This constitution was not put into effect; until the victory over the enemy, the Terreur must continue in Robespierre's opinion. While the Jacobins were betraying their own ideal of freedom, they succeeded in defeating the internal and external opponents of the revolution.

However, they lost more and more followers to the terror. In the summer of 1794, maximum wages were also introduced in addition to the maximum prices , which is why the interest of the sans-culottes in Jacobean politics decreased. In July, the revolutionary army won a decisive victory at Fleurus. Coercive measures no longer seemed so urgent. With the execution of former companions Robespierre lost his support in the convent. He was overthrown on July 27, 1794 and executed on July 28, 1794. That was the end of the terror. On the 9th Thermidor, Louis Legendre symbolically took the key to the club's conference venue. It was given back at the next meeting of the convent, and the Jacobins could continue to meet legally. The Legendre commissioned to do so finally closed the club in Paris on November 12, 1794.

In the time of the Thermidor reaction and the Directory

After the club was officially closed on November 12, 1794, there were still Jacobin representatives in the convent . This remnant, which became smaller and smaller due to deserters into the Plaine , was now called the summit ( La Crête ) in reference to the term of the mountain party . In another play on words, the members of this summit as Cretans (from French Les Crétois ). In the next few weeks, the Cretans then joined the remaining Cordeliers , until these too were banned on 20th Pluviose III (February 8, 1795). A general ban on everything Jacobean did not take place, however, so the important summit politician Thuriot was elected to the welfare committee on November 7, 1794 .

In the period that followed, however , the Directory still had to reckon with Jacobin revolts. In 1796, for example, former Jacobins, sansculottes and social revolutionaries gathered around the conspiracy of equals initiated by François Noël Babeuf with the aim of overthrowing the Directory and establishing a kind of communist society in France. In the northern Italian regions of Piedmont and Lombardy occupied by France, Filippo Buonarroti , one of the spokesmen of the equals , tried to instigate revolts with the help of Italian Jacobins. The plans and measures of the conspiracy of the equals were betrayed relatively early, however, their leaders arrested in May 1796 and sentenced the following year either to death (Babeuf, Darthé ) or to exile (Buonarroti).

Another attempt to form took place on July 6, 1799 under the name Réunion des Amis de la Liberté et de l'Égalité and the popular name Club du Manège . Already severely affected by Napoleon's coup d'état on 18th Brumaire , this attempt by the neo-Jacobins ended at the latest on 5th January 1801 with an arrest list of 133 leading members.

The name "Jacobin" was used increasingly insulting and denunciating by their opponents: Anyone who was so called should be publicly branded as "regicide". The Jacobins called themselves "patriots" .

"Jacobins" today

In the French political culture of the 20th century, the term Jacobinism within the left parties as well as the Gaullists denotes a nationalist and statist position, as well as moralizing tendencies, citizens through laws and prohibitions to an " ethical behavior " in the sense of the current mainstream to educate .

Jacobins outside France

After the outbreak of the French Revolution, Jacobin clubs were formed in some of the neighboring countries of France, who pursued similar political goals. Its members took part in revolutionary activities. Examples of this are the prehistory of the Italian Risorgimento or the Mainz Republic . In Mainz the Society of Friends of Freedom was founded as a club of German Jacobins just one day after the occupation by French revolutionary troops in October 1792 . a. the natural scientist Georg Forster belonged. The club promoted the establishment of the first state based on democratic principles on German soil, which only existed until the summer of 1793. After the conquest of revolutionary Mainz by Prussian and Austrian troops, there was so-called clubist persecution, to which many German Jacobins fell victim.

In 1794 Andreas Freiherr von Riedel and Franz Hebenstreit were brought to court as "Viennese Jacobins" in Vienna. Many supporters of the Enlightenment from civil servants and the army were imprisoned or executed in the course of this process. The head of the Republican officer Hebenstreit, who was executed at the time, was on display in the Vienna Crime Museum until 2012 and then removed from the exhibition as a result of an initiative by the “Vienna Lectures”.

Jacobins were also active in Cologne . One of them, Franz Theodor Biergans , published the political magazine "Brutus or the enemy of tyrants" there from 1795.

Chairwoman of the Jacobins during the French Revolution

- 1790: Maximilien de Robespierre

- November 1790: Gabriel de Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau

- October 1792: Georges Danton

- April 1793: Jean Paul Marat

- May 1794: Joseph Fouché

literature

- Lucas Chocomeli: Jacobins and Jacobinism in Switzerland. Work and ideology of a radical revolutionary minority 1789–1803. In: Freiburg studies in the early modern period . Vol. 11, Lang, Bern a. a. 2006, ISBN 3-03910-850-6 (also: Freiburg (Switzerland), Univ., Diss., 2005).

- Walter Grab : Jacobinism and Democracy in History and Literature. 14 treatises. In: Research on Young Hegelianism. Vol. 2, Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1998, ISBN 3-631-33206-8 .

- Hellmut G. Haasis : Give wings to freedom. The time of the German Jacobins 1789–1805. (= Rororo 8363 rororo non-fiction book ). 2 volumes, Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1988, ISBN 3-499-18363-3 .

- Hellmut G. Haasis: Dawn of the Republic. The German Democrats on the left bank of the Rhine 1789–1849. (= Ullstein book 35 199 = Ullstein materials ). Ullstein-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1984, ISBN 3-548-35199-9 .

Web links

- The Jacobins on terra-human.de.

- The German Jacobins on the left bank of the Rhine. From the Republic of Mainz to the first democratic constitution. Introduction by Hellmut G. Haasis to German Jacobinism.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Otto Flake The French Revolution , Manesse edition, p. 342

- ^ Albert Soboul The Great French Revolution , Athens, 1988, p. 385

- ↑ http://cityabc.at/index.php/Kriminalfall:_Der_Jakobiner_Hebenstreit