Republic of Mainz

The Mainz Republic was the first state based on bourgeois-democratic principles on German soil. The short-lived Free State existed from March to July 1793 in the area of Kurmainz on the left bank of the Rhine . Since he was under the protection of the French revolutionary troops , he is counted to the daughter republics of France (républiques sœurs) . The capital of the Mainz Republic was the French occupied Mainz , which gave it its name.

History of the Republic of Mainz

The establishment of the Mainz Republic was a consequence of the First Coalition War , in which an alliance of Austria , Prussia and some smaller German states took action against revolutionary France in order to restore absolute monarchy there .

Kurmainz on the eve of the Mainz Republic

The outbreak of the French Revolution caused some unrest on German soil in various smaller border territories. In the winter of 1789/90 Electoral Mainz and Electoral Palatinate troops moved out to end unrest in the imperial county of Leyen and the Ortenau. In February 1790, rumors of an uprising in the Aschaffenburg area led to another deployment of 231 Kurmainz soldiers. However, all of these operations were non-violent - in the case of the alleged unrest in Aschaffenburg, the whole situation even turned out to be misinformation. The situation was different in the case of the Reich execution against Liège, in the suppression of which 1500 Mainz soldiers were also involved (→ Liège Revolution ). Here, however, it became apparent for the first time that the armed population, motivated by the developments in France and Brabant, was able to offer sufficient resistance to regular troops of the ancien regime. At the same time, at the end of August 1790, riot-like unrest between journeymen and students broke out in Mainz, which the local military could no longer control without outside help. Only when the Hessian-Darmstadt troops were called in were they able to restore security and order and put an end to this so-called “ Mainz knot uprising ”.

In the past, the Mainz Jacobins and various historians have tried again and again to bring this unrest into a direct connection with the later Republic of Mainz. Although some journeymen allegedly put cockades on their hats and called themselves “patriots”, the unrest itself is part of a certain “tradition” of 22 other student unrest in Mainz, all of which took place in the 18th century. The Electoral Mainz government viewed the developments in France with great concern and reacted extremely cautiously to any form of bourgeois resentment, both in the wake of the knot riots and in later times. The electoral court chancellor Franz Joseph von Albini tightened controls and patrol activities, but at the same time instructed the Electoral Mainz officials to refrain from provoking the population. Even when 2000 Mainz soldiers were deployed in the fight against France, the otherwise customary special tax was waived. Instead, this company was financed through voluntary donations and for this purpose a regular festival was held in front of the gates of Mainz to celebrate the soldiers' departure.

Although a small part of the educated middle class in Mainz criticized the deployment of Mainz soldiers against the French Revolution, at that time there were only a few open supporters for the French cause. Basically, in Mainz, as in most German residences after the rapid successes of the allied intervention troops in France, it was assumed that the chapter of the French Revolution would soon be over. But as a result of the First Coalition War, the situation changed completely at the end of 1792.

Consequences of the First Coalition War for Mainz

At the beginning of the French Revolution , the European powers had initially shown themselves to be rather disinterested in the internal development of France. This changed after King Louis XVI's attempt to escape , which was foiled in June 1791 . in the border area to the Austrian Netherlands, controlled by royalist troops . Austria and Prussia responded to the forced return of the king to Paris and his temporary suspension on August 27, 1791 with the Pillnitz Declaration , in which they re-established Louis XVI. in his previous rights. The declaration was essentially at the instigation of the Count of Artois , a brother of Louis XVI. and leader of the counter-revolutionary French emigrants. The declaration made military intervention in France dependent on unlikely conditions, but it also did not exclude it. It was therefore perceived as a threat of war in Paris and contributed to the radicalization of the situation there. A majority of supporters of war now formed in the National Assembly. This even found the support of the king, who hoped for a defeat of his own country and with it the revolution.

On April 20, 1792, Louis XVI. the war in the name of France's Franz II - not in his capacity as Roman-German Emperor, but as King of Hungary and Bohemia. In France it was hoped that this would limit the war to a confrontation with the House of Habsburg. Due to an alliance treaty with Austria, Prussia also entered the war. A first French advance into the Austrian Netherlands was repulsed. The main army of the coalition, led by the Duke of Brunswick , invaded France via Luxembourg in the summer and threatened Paris.

On September 20, 1792, however, the Valmy cannonade stopped the coalition troops from Prussia, Austria and Hesse-Kassel. The French revolutionary troops went on the offensive and an army under General Custine advanced from Landau , which was then part of France , to the Rhine. Custine's troops enclosed a weak Mainz-Austrian corps in Speyer, forced it to surrender and advanced to Worms. In Mainz the news of the defeat of Speyer triggered a mass exodus. Not only did a large part of the nobility and clergy fled the city, also the elector Friedrich Karl Joseph von Erthal and a large part of the civil servants were evacuated. Even among the few soldiers of the occupation, who were also recruited from contingents from six different imperial territories, the news caused panic, over 90 soldiers left their posts at the same time and ran away.

On the other hand, Custine himself did not dare to advance directly to Mainz. Mainz was still the largest and strongest imperial fortress and the rumors of a nearby Hessian-Prussian army alone made Custine hesitate to venture a further advance with his weak army, which largely consisted of undisciplined national guards. In Mainz, however, pro-French citizens observed the events closely. They quickly recognized that Mainz as a fortress was completely under-manned and therefore knew that the Prussian and Hessian troops were inaccessible in the Trier area and could not possibly bring rapid relief. Several times, messengers like the doctor Georg von Wedekind secretly brought news from the city and gradually informed Custine about the real state of affairs. Mainz needed about 20,000 men for optimal defense, but even after about 3,000 citizens reported to defend the city, the defenders only brought about 5,800 men.

On October 19, 1792, Custine included the city. By artificially enlarged camps and simulated reinforcements, he discouraged the overwhelmed Mainz military leadership, so that it finally surrendered on October 21 without any real military need. Up to this point there is little open evidence that the broad mass of the Mainz population was in favor of the French attack. The memories of the French looting trains towards the end of the 17th century were still remembered in the Rhineland. In addition, there was no shortage of horror reports about French pillaging from Speyer and Worms. That is precisely why thousands of citizens joined the military to defend the city, and the university also provided a small corps of academics and students who took up positions on the ramparts.

But when the news of the capitulation spread, despair and anger at their own government spread among the population. The Nassau-Weilburg lieutenant colonel Massenbach stated: “As there was talk of the capitulation, the citizens said publicly that they had been sold, ran from their posts and threw away the rifles. Some complained about the elector, others about the governor. "

Contrary to expectations, however, Custine showed great leniency towards the common people when he marched in. His goal was to build a solid base in Mainz as a starting point and bridgehead for further actions in the future.

The German Jacobins

Under the name “Society of Friends of Freedom and Equality”, 20 citizens of the city founded the Mainz Jacobin Club the day after it was occupied . Like its later offshoots in Speyer and Worms , he joined the purposes of clarification for the ideals of the French Revolution of liberty, equality, fraternity , a well as for the establishment of a German Republic . Among its founders were the doctor Georg von Wedekind , the philosopher Andreas Joseph Hofmann , the theologian and canon lawyer Georg Wilhelm Böhmer , other professors and students at the university, such as the "revolutionary bard" and later journalist and journalist Friedrich Lehne, but also some merchants . After initial concerns, the university librarian and natural scientist Georg Forster joined him on November 5th . The club eventually had 492 registered members. Its president was temporarily Friedrich Georg Pape , a former Premonstratensian chorister and editor of the Mainzer Nationalzeitung. In an open letter of December 20, 1792 he attacked "Friedrich Wilhelm Hohenzollern, dermal king in Prussia" and signed with "Your and all kings enemy" . His provocative approach was also criticized by the leadership of the republic, as they feared a military reaction from Prussia.

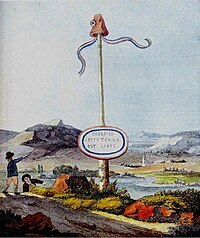

Custine tried to rule the conquered areas initially with the help of the old Kurmainz administration, but soon set up revolutionary-friendly administrations ( municipalities ) in the cities of Mainz, Speyer, Worms and Bingen as well as a general administration for the entire occupied area. In doing so, he relied on the German Jacobins , who now massively promoted the ideas of the French Revolution and the establishment of a republic in cities and villages - with pamphlets, posters, proclamations, but also with demonstrative propaganda campaigns such as the erection of trees of freedom . In mid-December 1792, a survey showed that in 29 of 40 municipalities surveyed, the majority of those eligible to vote (men aged 21 and over) were in favor of a reform of the state system based on the French model.

The establishment of the republic

Up to this point in time, all decisions of the population in the occupied area had been made without external pressure. This changed around the turn of the year 1792/93. Based on the experiences in the conquered areas of the Austrian Netherlands, whose population showed little willingness for revolution, the convention in Paris decided on December 15 to establish democratic orders in the occupied territories, if necessary against the will of the population.

Therefore, commissioners of the convent appeared in Mainz at the beginning of 1793. Together with the German Jacobins, they were supposed to prepare the elections for the municipalities and a constituent assembly, but demanded in advance of all voters to take an oath on the principles of the revolution. This oath was refused in many places, and the Jacobins even occasionally saw repression against the population. The elections for the Rhenish-German National Convention on February 24, 1793 were, by the standards of the time, nevertheless reasonably democratic. 130 towns and villages from the areas to the left of the Rhine and south of the Nahe sent their representatives to Mainz.

According to their self-image - unlike the members of the previously usual assemblies of estates - these were representatives of the entire population of an albeit limited area and thus formed a parliament in the modern sense. The first parliament in German history to be established according to democratic principles met on March 17, 1793 in the Mainz Deutschhaus , which is now the seat of the state parliament of Rhineland-Palatinate . It enacted that the following day

- Decree of the Rhenish-German National Convention of March 18, 1793, assembled in Mainz, whereby all previous arbitrary powers are abolished in the stripe of the country from Landau to Bingen am Rhein .

Article 1 of the decree states:

- "The whole line of land from Landau to Bingen, which sends deputies to this convent, should from now on constitute a free, independent, inseparable state that obeys communal laws based on freedom and equality."

And further in Article 2:

- "The only legitimate sovereign of this state, namely the free people, declares, through the voice of his deputies, all connection with the German emperor and empire to be canceled."

In the following, the decree declared all princely sovereign rights to be extinguished and threatened the previous sovereigns and everyone who should help them to regain their rule with the death penalty.

The Republic of Mainz issued copper coins with the legend REPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE in 1793. They were minted with the indication "1793" and the republican count "L'AN 2" around a bundle of lictors surrounded by branches. The nominal values 1 sol and 2 and 5 sols were produced.

The end of the republic

The delegates were aware that the Republic of Mainz, on its own, was not viable. Therefore they decided on March 23rd to apply to the convention in Paris for annexation to France. The delegation, which was sent to the French capital for this purpose, included Georg Forster , Adam Lux and the businessman Andreas Patocki. On March 30, the convention unanimously accepted the motion of the Mainz deputies. However, this decision no longer had any practical effects. For in the meantime Prussian troops had advanced into the territory of the Free State and had begun the siege of Mainz . In the four months until the surrender on July 23, the territory of the Republic of Mainz was limited to the city.

After the withdrawal of the French and the occupation by Prussian troops, the German Jacobins and their relatives were persecuted if they had not fled. They were mistreated and imprisoned, such as Felix Anton Blau and Friedrich Georg Pape ; their property was confiscated. The so-called clubist persecution did not end until 1795, when the French revolutionary troops again pushed forward to the Rhine and the entire area on the left bank of the Rhine was annexed to France for 20 years.

reception

The Republic of Mainz has been the subject of controversial discussions since the beginning of its existence. The proximity of its founders and supporters to the long-standing “ hereditary enemy France ” had a polarizing effect until the middle of the 20th century. Since the 1970s, the sometimes heated academic discussions about its political significance have increased: While some saw the Mainz republic as the first democratic state structure on the soil of today's Germany, others viewed it as a mere occupying regime. These different political interpretations of the republic and its protagonists also shaped the fierce controversies that occasionally occurred between scientists from the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic . In the wake of the 200th anniversary of the Mainz Republic in 1993, not only the studies and publications on the topic increased, but also the factuality and objectivity of the debate. For example, Franz Dumont , a historian who had devoted himself particularly intensively to the subject, revised his initially critical view shortly before his death in 2012. In a newspaper article he wrote: “The Mainz Republic - an exciting and at the same time difficult chapter of our city's history, often glorified, often damned. It had shortcomings and contradictions, was just as much an occupation regime as it was an attempt at democracy. It was unique for Germany, because no other German city was so early and intensely shaped by the striving for civil rights and democracy from the west as Mainz in 1792/93. The Republic of Mainz should therefore neither be dumped historically nor uncritically acclaimed; the memory of them is right and necessary! "

On the occasion of the 220th anniversary of the Republic of Mainz, the square in front of the Rhineland-Palatinate state parliament in the Mainz Deutschhaus was renamed to Platz der Mainzer Republik .

swell

- Heinz Boberach : German Jacobins. Republic of Mainz and Cisrhenans 1792–1798. Volume 1: Manual. Contributions to the democratic tradition in Germany. 2nd Edition. Hesse, Mainz 1982.

- Franz Dumont : The Republic of Mainz from 1792/93. Studies on the revolution in Rheinhessen and the Palatinate (= Alzeyer history sheets. Special issue 9). 2nd, expanded edition. Verlag der Rheinhessische Druckwerkstätte, Alzey 1993, ISBN 3-87854-090-6 (At the same time: Mainz, University, dissertation, 1978).

- Joseph Hansen : Sources and history of the Rhineland in the age of the French Revolution 1780–1801. Volume 2. 1792–1793, Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1933, reprint of the edition Hanstein Verlag, Bonn 1933, 2004, ISBN 3-7700-7619-2 .

- Heinrich Scheel (Ed.): The Mainzer Republic. Volume 1: Protocols of the Jacobin Club (= writings of the Central Institute for History. Volume 42, ISSN 0138-3566 ). 2nd, revised and supplemented edition. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1984.

- Heinrich Scheel (Ed.): The Mainzer Republic. Volume 2: Protocols of the Rhine-German National Convention with sources on its prehistory. (= Writings of the Central Institute for History. Volume 43). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1981.

- Heinrich Scheel (Ed.): The Mainzer Republic. Volume 3: The first bourgeois-democratic republic on German soil. (= Writings of the Central Institute for History. Volume 44). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-05-000817-2 .

literature

- Heinrich Scheel : The Mainz Republic. Berlin 1975

- Federal Archives and City of Mainz (ed.): German Jacobins - Mainzer Republic and Cisrhenans 1792–1798. Handbook, catalog and bibliography for the exhibition in Mainz town hall 1981, Mainz 1981

- Klaus Tervooren: The Republic of Mainz 1792/93. Dissertation, Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1982

- Walter Grab: A people must conquer their own freedom. On the history of the German Jacobins. Frankfurt am Main 1985

- Hellmut G. Haasis : Give wings to freedom. The time of the German Jacobins 1789–1805. 2 vols., Rowohlt, Reinbek 1988

- Peter Schneider : Mainz Republic and French Revolution. Mainz 1991

- The Republic of Mainz. The Rhine-German National Convention. Published by the Rhineland-Palatinate state parliament, Mainz 1993.

- Franz Dumont : The Republic of Mainz 1792/93. Studies on the revolution in Rheinhessen and the Palatinate. 2nd expanded edition, Alzey 1993, ISBN 3-87854-090-6

- Jörg Schweigard: The love of freedom calls us to the Rhine - Enlightenment, reform and revolution in Mainz. Casimir Katz, Gernsbach 2005, ISBN 3-925825-89-4

- Jörg Schweigard: Felix Anton Blau: early democrat, theologian, philanthropist . 1st edition. Logo-Verlag, Obernburg am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-939462-05-7

- Marco Michael Wagner: Georg Forster versus Adam Philippe Custine - Two revolutionaries in the Republic of Mainz? Munich 2008

- Franz Dumont: The Republic of Mainz 1792/93. French export of revolution and German attempt at democracy. Edited by Stefan Dumont and Ferdinand Scherf. Mainz 2013 (Issue 55 of the publication series of the Landtag Rhineland-Palatinate)

- Heinz Brauburger: The Mainz Republic 1792/93 - a place of democracy and freedom? Leinpfad-Verlag, Ingelheim 2015, ISBN 978-3-945782-05-7

- Hans Berkessel, Michael Matheus, Kai-Michael Sprenger (eds.): The Republic of Mainz and its significance for parliamentary democracy in Germany. Nünnerich-Asmus Verlag & Media GmbH, Mainz 201? ISBN 978-3-96176-072-5

- Jörg Schweigard: Friedrich Lehne. Revolutionary poet, early democrat, journalist. Logo Verlag, Obernburg am Main 2018. ISBN 978-3-939462-32-3 .

Play

- Rolf Schneider : The Republic of Mainz. Mainz 1980

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ The Raurak Republic had already been formed at the end of 1792 from those parts of the Principality of Basel that were still part of the empire at that time , but whose population mostly spoke French .

- ^ Mathy, Helmut: Studies and sources on jurisdiction at the University of Mainz . In: Petry, Ludwig (Ed.): Festschrift Johannes Bärmann . Berlin 1966, p. 110-160 .

- ^ Karl Otmar von Aretin: From the German Empire to the German Confederation. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1993, ISBN 3-525-33583-0 , p. 24.

- ↑ Lübcke, Christian: Kurmainzer military and land storm in the first and second coalition war . Ed .: RWM-Verlag. Paderborn 2016, p. 232 f .

- ↑ Lübcke, Christian: Kurmainzer military and land storm in the first and second coalition war . Ed .: RWM-Verlag. Paderborn 2016, p. 253 .

- ↑ Georg Wilhelm Böhmer in the Brockhaus : The Mainz Clubists at zeno.org

- ^ Jörg Schweigard: Friedrich Lehne. Revolutionary poet, early democrat, journalist. 1st edition. Logo Verlag, Obernburg / Main 2018, ISBN 978-3-939462-32-3 .

- ↑ Klaus Harpprecht : "Only free people have a fatherland", Georg Forster and the Republic of Mainz , lecture event in the Rhineland-Palatinate state parliament on November 24, 2004. (PDF, 42 pages)

- ^ Dumont: Republic of Mainz..Studien..2. Ed., P. 195.

- ↑ Dr. des. Michael Huyer: France and Mainz - history around 1800 in the mirror of monuments . State Center for Civic Education Rhineland-Palatinate, Mainz 3/2001, PDF document

- ^ Gerhard Schön, German coin catalog 18th century, Mainz, Stadt, No. 1–3

- ↑ A detailed historiography can be found in Bernd Blisch and Hans-Jürgen Bömelburg: 200 Years of the Mainz Republic. The difficulties of dealing with a cumbersome past. In: Mainz history sheets: All about the freedom tree. 200 years of the Republic of Mainz. Issue 8, Association for Social History Mainz (Ed.), Mainz 1993. ISSN 0178-5761

- ↑ Quoted from Franz Dumont: Mainzer Republik: Franz Dumont sees months of the first democratic model on German soil inadequately appreciated ( Memento from August 29, 2012 in the Internet Archive ). In: Mainzer Allgemeine Zeitung , June 26, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ↑ Press release of the Mainz State Chancellery (March 18, 2013) .

- ↑ The Republic of Mainz - Schneider, Rolf. Retrieved December 15, 2018 .