Emperor penguin

| Emperor penguin | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Emperor penguins ( Aptenodytes forsteri ) with chicks |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Aptenodytes forsteri | ||||||||||||

| Gray , 1844 |

The Emperor Penguin ( Aptenodytes forsteri ) is the largest type from the family of penguins (Spheniscidae) and ranks along with the King Penguin ( Aptenodytes patagonicus ) to the genus of large penguins ( Aptenodytes ). No subspecies are recognized for the emperor penguin. Due to numerous infotainment and documentary films, the emperor penguin is one of the most famous penguin species. The film The Journey of the Penguins , which deals with brood care of this species, won an Oscar in 2006.

The population of the emperor penguin was classified in the IUCN's Red List of Threatened Species in 2016 as “ Near Threatened (NT) ” = “potentially endangered”.

Appearance

The emperor penguin is between 100 and 130 centimeters tall and weighs between 22 and 37 kilograms. There is neither a sexual dimorphism nor a seasonal difference in plumage color.

Adult emperor penguins have a black head, a black chin, and a black throat. The transition between the throat color and the yellowish-white breast is very sharp. Emperor penguins have noticeable ear tags that are about four centimeters wide. They are bright yellow at the top and then turn a paler yellow. The upper side of the body is dark gray-blue and looks brownish shortly before moulting when the plumage is very worn. The underside of the body is white and the upper chest is yellowish. The fins are whitish on the underside with a dark spot on the tip. The beak is about eight inches long and very narrow. The upper beak is black, the lower beak varies between pink, orange or purple, depending on the individual. The iris is brown. The feet and legs are black, the outer side of the legs is feathered.

Fledglings are similar to adults, but they are a little smaller and their ear patches are initially whitish. The chin and throat are whitish gray, the beak is black. The chicks have a silver-gray down dress with a striking white face mask. The head is black.

It can only be confused with the king penguin . However, this is a bit smaller. The yellow-orange plumage areas are a little brighter and more sharply demarcated than the emperor penguin. The legs of the king penguin are also not feathered.

voice

Emperor penguins have loud trumpet-like calls. Their vocalizations can mainly be heard in the breeding colonies, but occasionally they also make contact sounds in open water. Emperor penguins that make contact calls on land usually point their beak up. The contact call lasts about a second. Calls related to pairing are more complex in rhythm and consist of a series of repeated syllables interrupted by short pauses. They are called by both sexes. The call of the female has more syllables. The calls are individually distinguishable based on the order of the syllables and the pauses between them. These calls can be heard especially during the pairing period. Mated birds are not very happy to call; calls can only be heard again after they have laid their eggs. Couples then often call together.

Threat calls are usually very short and very variable. Some of them are reminiscent of the contact calls, and sometimes resemble a grunt. The chicks' contact calls are short and last about half a second. The individual call pattern of a chick develops shortly after hatching and hardly changes during the nestling period. Reputation plays a significant role in finding parent birds and chicks within the breeding colony.

Distribution and existence

The emperor penguin is circumpolar and is the southernmost penguin. It is also the only vertebrate that can linger in the Antarctic inland ice for a long time. The habitat of the emperor penguin is the cold waters of the Antarctic zone. He stays within the pack ice boundaries . Its breeding areas are on sea ice between 66 ° and 78 ° S. Breeding colonies are found on the edge of the Antarctic , the Antarctic Peninsula and adjacent islands. Odd visitors are occasionally observed north of 65 ° S and are occasionally seen off South Georgia, Heard Island and New Zealand.

The stock is considered stable. The number of sexually mature and thus reproductive emperor penguins has been estimated at 270,000 to 350,000 individuals. Recently, based on the evaluation of satellite images, a number of 595,000 animals in 46 colonies can be assumed. Breeding colonies usually lie on flat sea ice and are either near the edge of the ice or up to 18 kilometers inland. They are often in the lee of ice cliffs, hills or mountains.

Global warming threat

The survivability of the emperor penguins depends on overcoming the climate crisis through compliance with the Paris Agreement . On the basis of simulation models it can be predicted for the “business as usual” greenhouse gas emission scenario that 80% of the colonies will practically be extinct by 2100 and the total number of emperor penguins is expected to decrease by at least 81%. If the goals of the Paris Agreement are complied with, however, there will be places of refuge for emperor penguins that ensure their survival in Antarctica and by the year 2100, according to the 1.5 ° C and 2 ° C climate scenarios of Paris, only 19% and 31% respectively will be forecast % of colonies are practically extinct; As a result, assuming the 1.5 ° C of Paris, the global population will decline by at least 31% and assuming the 2 ° C of Paris by 44%, with the population stabilizing from around 2060.

nutrition

The emperor penguin is a sea bird and only hunts in the sea . It feeds on fish , octopus and krill . Emperor penguins hunt in groups. They swim right into a school of fish, move quickly to and fro and snap at anything that comes in front of their beaks. Smaller prey animals eat them directly in the water, with larger prey animals they have to come to the surface of the water to break them up there. When hunting, the emperor penguins cover great distances and reach speeds of up to 36 km / h and depths of up to 535 meters. If necessary, they can stay underwater for up to twenty minutes. The lighter it is, the deeper they dive. As sight hunters, they do not track their prey through their hearing or echo sounder , but have to see it in order to catch it.

Protection against cooling down

Penguins have plumage that has been specially adapted in the course of evolution . They have many short feathers that together form a dense plumage. With the help of their beak and their feet, the penguins rub their plumage with an oily, tranquil gland secretion, which is formed by the rump gland (skin gland). This makes the plumage completely waterproof. The secretion keeps the feathers soft and supple and also inhibits the growth of fungi and bacteria. A penguin excretes up to one hundred grams of secretion every day at the preen gland. Penguins spend a lot of time caring for their plumage every day. Another peculiarity can be observed during the moult , which occurs once a year . While many other birds have their plumage thinned or bald spots become visible during moult, this is not the case with penguins. With them the new feathers grow below the feather shafts of the old plumage. As the new feathers get bigger, gradually push the old shafts outward until the old feathers fall off. Then a new spring appears underneath, which immediately closes the gap and thus maintains the thermal protection.

Under the penguin plumage, penguins also have a thick layer of fat, which, except for the emperor penguin, does not significantly contribute to protection from the cold. The plumage makes up around 90% of the isolation in a penguin. In contrast to whales or seals , the penguin's fat layer mainly serves as a nutrient store and hardly as protection from the cold. How efficiently the plumage prevents body heat from escaping to the outside can be seen in the case of emperor penguins, which are largely covered with snow after snowstorms. The snow practically does not begin to melt because the temperature on the body surface is only marginally above 0 ° C.

The feet of the emperor penguins have only a very low blood supply on the underside and give off little heat to the icy ground. The feet of the males have a strong blood supply on the upper side on which the egg lies.

While a penguin colony spreads out irregularly on the ice surface during the day when the sun is shining , the penguins move together to so-called huddles from sunset to protect themselves against the cold and wind, a behavior necessary for survival, especially during storms.

Reproduction and rearing of the young

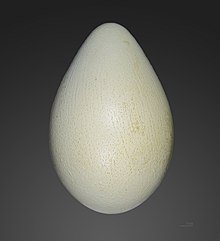

Emperor penguins reproduce for the first time when they are three to six years old. They migrate up to 200 kilometers inland across the frozen sea to their breeding grounds. These must be in areas where the ice does not melt in the Antarctic summer. In April, the mating season begins with courtship and in May / June (Antarctic winter) they begin to breed. Unlike other penguin species, they do not build nests, but instead form colonies together in valleys or in the slipstream of hills, in which the animals often change locations. On warm days, the colonies pull apart widely. The mating partners recognize each other by vocal characteristics, with the often excess females vying for the males' favor. The female lays a single egg , which weighs around 450 grams, leaves the breeding colony after being laid and returns to the sea, where it searches for food. The male lays the egg on his feet, covers it with his belly fold and carries it around. It can happen that the egg rolls off your feet onto the ice. In this case, the embryo inevitably dies after a minute or two. In order to protect themselves from the icy wind, the animals move closer together, but constantly change their places, so that each animal stands sometimes on the edge and sometimes in the warmer interior of the colony, which is drawn together in a circle.

The chicks hatch after about 64 days of breeding season from mid-July and have until January (summer in the southern hemisphere) to fledge. They have a fine gray fluff. They have black heads and a white ring around their eyes. Initially, they remain in the males' belly fold. The males feed their young with a milky substance ( trophallaxis ), whereby they lose a third of their body weight during the breeding phase.

The females return to the chick with around three kilograms of pre-digested fish. The chick gets its first fish from the female. Now the males migrate to the sea to replenish their reserves. When the very young chicks are exchanged from fathers to mothers, the change must take place in seconds, as the chicks can withstand the Antarctic temperatures only for a few seconds. Many young animals die in these swap maneuvers. The old animals now constantly alternate with feeding. Since it is now summer in Antarctica, the advantage of this breeding strategy becomes apparent: the chick needs a lot of food to grow, and the way to the sea is noticeably shorter as the pack ice melts.

While the chicks are waiting for their parents, they form what is known as a crèche , a collection of young birds. They stand close together to protect themselves from the Antarctic cold.

During the first moult, the offspring lose their downy feathers and get the feathers of the adults. The pups leave the penguin colony at around six months of age and only return there three to six years later to breed on their own.

Natural enemies

Emperor penguins have very few enemies and can live up to 50 years, although they typically die around the age of 20. The only enemies that could kill an adult emperor penguin in or near the water are leopard seals or orcas .

On the pack ice it happens that skuas and giant petrels prey on chicks from the emperor penguins. The greatest threat comes from the giant petrel, which is responsible for up to a third of the losses among young emperor penguins.

Movies

- The long march of the penguins . Documentary, Antarctic Explorers, 1997.

- Survivalist - Emperor Penguins in Antarctica . Documentary, Marco Polo Film, 2006.

- Happy feet . American-Australian animated film directed by George Miller from 2006.

- Happy Feet 2 . American-Australian animated film directed by George Miller from 2011. Continuation of Happy Feet .

- The emperor penguin became known to a large audience through the film The Journey of the Penguins from 2005. This film reports on the migration, mating and brood care behavior of the emperor penguins from the humanized ( anthropomorphizing ) narrative perspective of the animals. It does not meet the strict scientific requirements of a documentary film, but was commercially successful and was honored as “Best Documentary (Long Form)” at the 2006 Academy Awards .

- The journey of the penguins 2 . Documentary from 2017.

literature

- Tony D. Williams: The Penguins . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1995, ISBN 0-19-854667-X

Web links

- Aptenodytes forsteri in the Red List of Threatened Species of the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed January 2 of 2009.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Aptenodytes forsteri in the Internet Bird Collection

Individual evidence

- ↑ Aptenodytes forsteri in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2016 Posted by: BirdLife International, 2016. Retrieved on 3 October 2017th

- ↑ BirdLife Factsheet on the Emperor Penguin . Retrieved September 7, 2013.

- ^ Williams, p. 153

- ↑ Williams, pp. 153-155.

- ^ Williams, p. 155.

- ^ Williams, p. 153.

- ↑ BirdLife Factsheet on the Emperor Penguin . Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ↑ Peter T. Fretwell, Michelle A. LaRue et al. a .: An Emperor Penguin Population Estimate: The First Global, Synoptic Survey of a Species from Space. In: PLoS ONE. 7, 2012, p. E33751, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0033751 . - Quoted in The miraculous reproduction of the emperor penguins - Spiegel Online . Retrieved April 13, 2012.

- ^ Emperor penguins in the Antarctic census from space

- ^ Williams, p. 155.

- ↑ a b Stéphanie Jenouvrier et al. (2019) The Paris Agreement objectives will likely halt future declines of emperor penguins. Global Change Biology . https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14864

- ↑ Jonas Plate: Swarming transitions in discrete models

- ↑ Penguin "Huddles": Cuddling against the cold nordbayern.de from June 3, 2011