Cold progression

Cold progression is the additional tax burden that arises over time if the key figures of a progressive tax rate are not adjusted to the rate of price increase . In a broader sense, this also includes the additional tax burden that occurs when the basic tariff values are not adjusted to the average income development. On the other hand, progressive taxation, which aims only at the income differences between the taxpayers in one and the same assessment period , does not belong to this situation.

The catchphrase fiscal dividend is also used less often for the cold progression.

definition

For a better understanding, a distinction must first be made between two terms:

- Nominal income (this is income valued in money without taking actual purchasing power into account.)

- Real income (This corresponds to the goods and services one can buy based on current prices.)

Cold progression in the strict sense

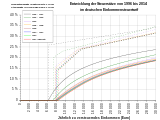

The cold progression in the narrower sense is the additional tax burden that occurs over time if, in the case of a progressive income tax rate, the basic tax allowance and the rate characteristic curve are not adjusted to the rate of price increase. The graph on the right shows the relative burden of the cold progression as a function of the taxable income and inflation. The cold progression leads to a relatively higher income tax burden, especially for lower and middle incomes, with the effect being greatest at the end point of a progression zone.

The problem here is to determine a value for the actually relevant inflation. It is sometimes assumed that government agencies conceal actual inflation and publish values that are too low. Apart from the hedonic method and shifts in the shopping cart, which are often cited here , the individual rate of price increases also depends on the respective consumer behavior. Someone with a low income has a different consumer behavior than someone with a middle or high income. Instead of assuming a single value for the price increase across all income classes, it can therefore make sense to use different inflation rates for the different income groups.

Cold progression in the broader sense

Cold progression in the broader sense is distinguished from cold progression in the narrower sense in the specialist literature. This is the additional tax burden that occurs when the basic tax-free allowance and tariff profile are not adjusted to the average development of nominal income. In this case, the tax revenue grows faster than the tax base. That is why the cold progression is also referred to in the broader sense as a secret tax increase .

Whether the tax rate should be regularly adjusted to the nominal income development is controversial. Depending on the tariff structure, it could be seen as sensible to concentrate relief more in the lower and middle income bracket.

misunderstandings

Under no circumstances does a wage increase mean that there is less money in the pocket after the wage increase than before, even if this impression is repeatedly created in the public discussion, especially by politicians and some media. However, the cold progression causes a decrease in real income if the increase in income after tax does not exceed the rate of inflation. Hence this is seen in part as an income development problem, not the tax system. Details can be found in the Calculation section .

Compensating for the cold progression does not necessarily lead to a drop in government revenues if the increase in tax revenues is limited to the mere compensation of inflation and incomes rise accordingly. On the other hand, waiving the compensation of the cold progression leads to a secret tax increase when incomes rise .

Differentiation of normal progression from cold progression

Through progressive income taxation , just normal progression called, which is income inequality more or less reduced. This leads to a redistribution through a greater burden on higher incomes. The normal progression is aimed at the income differences between taxpayers in the same tax period .

In contrast to this, the cold progression leads to a relatively higher burden , especially for lower and middle incomes. The cold progression works through the changes over time , especially when these are added up over several years.

A study by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung shows that the relative exposure to cold progression is highest at the respective endpoints of the progression zones. The additional burden at 1.5% inflation moves in the gross income range of around 13,000 to 75,000 euros in the interval from 0.15 to 0.2 percent for the year 2014. The graphics in the sections below show this situation in a similar way on taxable income with a price increase rate of 2% in relation to the loss of real income.

The cold progression thus leads to a higher burden on the lower and middle income brackets, especially over longer periods of time, due to the failure to adapt to price and wage developments. The differences between the taxpayers in one and the same assessment period then tend to decrease, which contradicts the original purpose of normal progression .

calculation

Either a real income index or a rate of change (relative change) compared to an earlier reference point in time (mostly previous year) is used as a comparative value to assess the effect of the “cold progression”.

The change in real income (caused by cold progression) is calculated as follows:

It is

- = Relative change in real income

- = Relative change in income after tax

- = Relative change in prices

- General example 1

In the graphic opposite, an inflation rate of 2% is assumed for the sake of simplicity. In this case, an increase in nominal income equal to the inflation rate leads to a higher income tax, although the real income and thus the taxpayer's economic performance has not increased. If the nominal income remains unchanged, the income tax remains unchanged, although the real income falls due to inflation.

Example: Let inflation be 2 percent in one year. In the same year, a taxpayer achieves an increase in nominal income before tax of also 2 percent. This would balance out purchasing power if his tax burden did not rise due to the progressive tariff due to his higher nominal income. After deducting VAT, he has less purchasing power despite a higher nominal income.

- General example 2

If the income after tax (nominal) was 10,000 euros in the last year and 10,200 euros in the current year, the relative change in income after tax is 2%. If the prices have also increased by 2%, the following applies

- (Real income stays the same)

However, if the progressive effect (higher tax rate) changes the income after tax (nominal) in the current year only to 10,100 euros (plus 1%), there is a loss of purchasing power:

- (Real income is falling)

However, it would be wrong to believe that by foregoing the wage increase one would have a higher real income. Then the income after tax (nominal) would only be 10,000 euros in the current year. Then would apply

- (Real income would drop even more)

If the income before tax (nominal) rises to 10,400 euros (plus 4%), the opposite applies

- (Real income increases)

By definition, when calculating the effect of the “cold progression”, only the real change in income caused by the tax rate should be determined. Changes in gross income do not have the same effect on the tax base if, for example, tax exemptions change over time. For this reason, other effects that arise from changes in tax exemptions (income-related expenses, special expenses, pension lump sum) or tax reductions (individual deductions directly from the collectively agreed income tax) must not be taken into account. Only those calculation rules that are directly part of the income tax rate are to be used. This calculates the change in the amount of tax, post-tax income and real income. The following example should clarify this:

- General example 3

- A price increase rate of 2% / year is assumed.

- Nominal income (2009) = 24,000 euros / year

- Tax rate (2009) = 19.8%

- Tax rate (2013) = 21.3% (if income increases by 2% / year)

The following tables show the calculation with two different changes in income. If the rate of price increase and the rate of increase in wages are the same, the "cold progression in the narrower sense" can be calculated:

| year | Change prices |

Change in pre-tax income |

Average tax rate |

Income before tax (nominal) |

Tax amount (nominal) |

Change in tax amount |

Income after tax (nominal) |

Change in income after tax |

Change (real) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 19.8% | € 24,000 | € 4,745 | € 19,255 | |||||

| 2010 | + 2.0% | + 2.0% | 20.1% | € 24,480 | € 4,920 | + 3.69% | € 19,560 | +1.58% | −0.41% |

| 2011 | + 2.0% | + 2.0% | 20.4% | € 24,970 | € 5,098 | + 3.62% | € 19,872 | +1.59% | −0.40% |

| 2012 | + 2.0% | + 2.0% | 20.9% | € 25,469 | € 5,312 | + 4.20% | € 20,157 | +1.44% | −0.55% |

| 2013 | + 2.0% | + 2.0% | 21.3% | € 25,978 | € 5,532 | + 4.14% | € 20,446 | +1.44% | −0.55% |

If the wage increase rate is greater than the price increase rate, then it is a matter of the “cold progression in the broader sense”. There are different opinions as to whether this part of the progression is desirable or undesirable.

| year | Change prices |

Change in pre-tax income |

Average tax rate |

Income before tax (nominal) |

Tax amount (nominal) |

Change in tax amount |

Income after tax (nominal) |

Change in income after tax |

Change (real) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 19.8% | € 24,000 | € 4,745 | € 19,255 | |||||

| 2010 | + 2.0% | + 4.0% | 20.4% | € 24,960 | € 5,095 | + 7.38% | € 19,865 | + 3.17% | +1.15% |

| 2011 | + 2.0% | + 4.0% | 21.3% | € 25,958 | € 5,523 | + 8.40% | € 20,435 | + 2.87% | + 0.85% |

| 2012 | + 2.0% | + 4.0% | 22.1% | € 26,997 | € 5,972 | + 8.13% | € 21,025 | + 2.88% | + 0.87% |

| 2013 | + 2.0% | + 4.0% | 22.9% | € 28,077 | € 6,439 | + 7.82% | € 21,638 | + 2.91% | + 0.90% |

Since three variables are included in these calculations, there are also three ways to counteract the loss of real income:

- Increase in income or change in income distribution

- Lowering consumer prices

- Change of tariff course

Which measure is to be regarded as the best is the subject of controversial discussion in the political debate. This article deals primarily with the tariff history.

Possibility of elimination

General

Secret tax increases through cold progression can be avoided by adjusting the income tax rate to the development of purchasing power. To avoid constant discussion about adjustment, some voices suggest an automatic adjustment mechanism. For example, the Institute for Applied Economic Research proposed a link to price increases or to the growth rate of national income. Some authors call this a “tariff on wheels”. However, the Federal Ministry of Finance sees the risk of boosting inflation.

The problem could also be solved by abolishing tax progression , for example by introducing a uniform tax rate or a flat tax , in each case without a basic tax allowance . However, these proposals are criticized as socially unjust, since taxation based on performance through the flat tax is insufficient and the flat tax does not take place at all. The government of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher introduced the poll tax community charge (better known as poll tax ) in Great Britain in the late 1980s . However, 18 million Britons refused to pay the tax and violent protests broke out. Ultimately, the community charge was what caused the crisis and the resignation of the Thatcher government. It was replaced in 1993 by the council tax.

Development in Germany

Income in Germany doubled from 1975 to 1989, while the benchmark of 130,020 DM (66,480 €), at which the top tax rate of 56% began to take effect, remained the same. This meant that more and more taxpayers “grew into” a higher tax rate. From 1990 onwards, this situation was alleviated by changing the tariff structure . The introduction of a linear progressive tariff in 1990 eliminated the so-called " middle class belly ". In the following years until today this course has changed again and again.

From 1999 to 2005, the income tax rates were greatly reduced under the Schröder / Fischer government (see the following diagrams). Since 2004, there has been a kink due to the only partially linear-progressive tariff, which in the political discussion is sometimes referred to as the “middle class belly”. Under the Merkel / Steinmeier government, this process was maintained until 2008 for taxable annual incomes below 250,000 euros. For 2009 and 2010, the basic tax rate was reduced to 14%, the basic tax-free amount slightly increased to 8,004 euros and the upper benchmarks to 52,881 euros and 250,730 euros (2010 tariff). In the years 2013 to 2015, only the basic tax-free amount was increased without changing the rest of the tariff. For 2016, in addition to the basic tax allowance, the other key figures were also adjusted, but different factors were applied. For example, the upper benchmark was only increased by 1.48 percent to 53,666 euros, while the increase in the basic tax allowance was 2.12 percent.

There is still no automatic adjustment to the inflation rate. It is often said that such an automatic adjustment does not require any “counter-financing” because it is only a matter of generating no further tax revenue beyond the pure inflation adjustment. Instead, the additional income from the cold progression is firmly planned every year in budget planning and calls for the abolition of the cold progression are regularly blocked with the factually inaccurate demand for "counter-financing". Sometimes it is also stated that the cold progression since 1991 has de facto been clearly overcompensated by tax policy in almost all cases. In political discourse, the cold progression is therefore often only misused to call for tax cuts in general.

The FDP demanded before the parliamentary elections in 2009 the introduction of a step tariff , such as in Austria, but alone the problem of cold progression does not solve for themselves. The legislature should therefore be obliged to review the tax rate every two years and adjust it if necessary.

According to a study by the Federal Ministry of Finance, the annual burden in 2013 due to the cold progression as a result of low inflation averaged EUR 16 per capita; in 2014 it had no effect at all due to the increase in the tax-free subsistence level. This is also expected for the two following years.

The following table shows the timing of selected benchmarks in relation to the average wage. The solidarity surcharge is not included. It should be noted that the average wage is an average of gross income , while the basic tariff values represent the taxable income . A direct comparison is therefore not possible. The following table shows only one trend.

| year | Throughput schnitts- of charge (West) |

Basic free- draw |

Proportion of the basic allowance from the transit schnitts- pecuniary |

End of the progression zone |

Marginal tax rate at the end of the progression zone |

End of the progression zone relative to the average wage |

Progression- sions- wide |

Contribution breaker size limit in the pension insurance (West) |

Contribution breaker size limit RV relative to the average of charge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 (DM) | 6 101 | 1,680 | 28% | 110 040 | 53% | 18.04 | 65.50 | 10 200 | 1.67 |

| 1970 (DM) | 13 343 | 1,680 | 13% | 110 040 | 53% | 8.25 | 65.50 | 21 600 | 1.62 |

| 1980 (DM) | 29 485 | 3690 | 13% | 130,000 | 56% | 4.41 | 36.23 | 50 400 | 1.71 |

| 1990 (DM) | 41 946 | 5 616 | 13% | 120 042 | 53% | 2.86 | 21.38 | 75 600 | 1.80 |

| 1996 (DM) | 51 678 | 12 095 | 23% | 120 042 | 53% | 2.32 | 9.92 | 96,000 | 1.86 |

| 2000 (DM) | 54 256 | 13 499 | 25% | 114 696 | 51% | 2.11 | 8.50 | 103 200 | 1.90 |

| 2010 (EUR) | 31 144 | 8 004 | 26% | 52,882

(250 731) |

42%

(45%) |

1.70

(8.05) |

6.61

(29.6) |

66,000 | 2.12 |

| 2016 (EUR) | 36 267 | 8 652 | 24% | 53 665

(254 447) |

42%

(45%) |

1.48

(7.02) |

6.20

(29.4) |

74 400 | 2.05 |

The significant increase in the basic tax allowance in 1996 is due to the case law of the Federal Constitutional Court . Since then, the basic tax-free allowance in relation to the average wage has only fluctuated in a small corridor and almost corresponds to the ratio of 1960. In contrast, the ratio of the end of the progression zone to the average wage has steadily decreased over the years. Analogously, the width of the progression zone has also decreased. Various sources see this as a cause for the cold progression. However, this does not take into account that the marginal tax rate was reduced from 53% to 42% at the end of the linear progression zone, which resulted in tax relief.

The assessment ceiling in the pension insurance is listed here as an example as a further benchmark that is closely related to the development of wages. Obviously, there is a regular adjustment here, which even goes beyond the mere adaptation to the wage development.

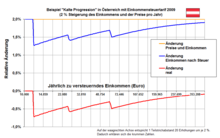

Situation in Austria

In Austria there is a tiered tariff ( tiered -progressive tariff) in income tax law , which can also trigger a cold progression. This is particularly high at the transition points between the steps. The graph on the right shows that the relative losses in real income are higher in the area of the levels than next to them. The problem must be solved here by a suitable shift in the key values of the levels.

There is also a discussion in Austria about creeping tax increases. The income tax rate from 2009 was finally changed on January 1, 2016.

Situation in Switzerland

In Switzerland, the legislature is legally bound to periodically compensate for the cold progression ( Art. 128 Para. 3 BV , Art. 39 DBG ). As soon as the cumulative inflation is 7 percent above the last status, the tax rate must be adjusted. The cold progression for the federal tax has been offset annually since 2010, which some cantons have already done for the much higher state tax and the associated municipal tax. There are similar regulations to compensate for the cold progression, for example in France and Canada.

Situation in other countries

In some other countries, there are also binding regulations to reduce cold progression. The income tax rate and important tax deductions are regularly adjusted to the general price trend or the average income trend. This process is also known as indexing. There is a statutory indexation of the income tax rate, for example, in the USA, Canada, Belgium, Denmark and the Netherlands.

Web links

- Income tax calculator for Germany with annual comparison taking inflation into account - historical tax formulas from 1958

- Claus Hulverscheidt: Cold Progression - The Pumped Up Monster, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung from May 5, 2014.

- Cold progression simply explained (explanatory video) on YouTube

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dirk Schindler, Finanzwissenschaft I - Institutions ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , P. 131, para. 12.2.4, University of Konstanz

- ^ Thilo Schaefer: Income tax without cold progression. Konrad Adenauer Foundation, November 2014, accessed on August 9, 2016 .

- ^ A b Andreas Marquart, Phillip Bagus: Why others get richer at your expense . 1st edition 2014. FinanzBook, ISBN 978-3-89879-857-0 , pp. 95 ff., 102 ff .

- ↑ Dirk Müller: Crash Course . Paperback June 2010 edition. Knaur, ISBN 978-3-426-78295-8 , pp. 27 ff .

- ^ W. Scherf: Public Finances, 2nd edition, p. 297ff.

- ↑ a b compare, for example, DIW weekly report, No. 12/2012, page 20.

- ↑ a b c IMK Report April 2014: Section Cold Progression: Sober Analysis Required, accessed on May 16, 2014.

- ↑ Compare, for example, ARD Panorama, broadcast on May 8, 2014, 9:45 p.m. The phrase used there "... and then you slide one step higher in the tax system and thus have less money in your pocket than before" is misleading.

- ^ Thilo Schaefer: Income tax without cold progression. Konrad Adenauer Foundation, November 2014, accessed on August 9, 2016 .

- ↑ ibid., Figure 3-1: "Stress from cold progression relative to income" on page 8

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Germany: “Taxable income”; Austria: “Income”; Switzerland: "Taxable Income"

- ↑ BMF: Cold Progression: Progressive Income Tax Tariff (Infographic)

- ↑ a b Peter Gottfried, Daniela Witczak: Macroeconomic effects of the "secret tax progression" and tax policy options to relieve the burden on citizens and the economy. Expert opinion on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology, IAW short report 1/2008, 2008 (PDF; 3.4 MB)

- ↑ a b c Austrian income tax rate (since January 1, 2009), calculated without deductions

- ↑ a b c Claus Hulverscheidt: Cold progression. The inflated monster. Süddeutsche Zeitung, May 5, 2014, accessed on May 6, 2014 .

- ↑ Cold Progression: Definition of terms, ( Memento from January 4, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Federal Ministry of Finance, April 1, 2008.

- ↑ cf. for example Nachdenkseiten.de

- ↑ a b cf. Barbara Bültmann: The cold progression: Let the citizen what is the citizen! In: http://www.stiftung-marktwirtschaft.de/ . Market Economy Foundation, May 2014, accessed on July 29, 2015 .

- ↑ FDP election program 2009, page 6

- ↑ Study by the Federal Ministry of Finance "There is currently no cold progression in Germany" at SZ-Online from December 12, 2014.

- ↑ cf. Average wage

- ↑ a b cf. Income tax (Germany)

- ↑ This comparison is only possible to a very limited extent because the average wage is an average of gross income , while the basic tariff values represent the taxable income .

- ↑ End of the progression zone / basic tax allowance

- ↑ cf. Assessment ceiling

- ↑ a b Values in brackets represent the additional top tax rate introduced from 2007

- ↑ The average wage for 2016 is provisional

- ↑ Increase in the basic allowance due to unconstitutional taxation of the subsistence level, cf. BVerfGE 87, 153 - basic allowance

- ↑ Hans-Georg Jatzek: And secretly the tax burden is increasing. December 16, 2013, accessed August 2, 2016 .

- ↑ Tax myths, Myth 15, page 5f, Figures 6 and 7

- ^ DiePresse.com: Cold Progression: A tax increase every year, accessed on May 3, 2014.

- ↑ Wirtschaftsblatt.at: Berlin goes to war against cold progression, ( Memento from May 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on May 3, 2014.

- ↑ Art. 128 Para. 3 Federal Constitution , Art. 39 Federal Act on Direct Federal Taxes

- ^ Resolution of the National Council of April 29, 2009, according to: Neue Zürcher Zeitung No. 99, April 30, 2009, p. 13.

- ↑ How rising taxes eat up your wage increase, in Der Spiegel on April 25, 2008.

- ↑ J. Lemmer: Regulations for the Reduction of Cold Progression in International Comparison, 2014 (PDF; 1,122 kB).