Cambodian Civil War

| date | 1970-1975 |

|---|---|

| place | Cambodia |

| output | Khmer Rouge victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

| losses | |

| approx. 200,000 to 300,000 dead and 750,000 wounded |

|

The Cambodian Civil War was a war between the Communist Party of Kampuchea (also known as the Khmer Rouge ) and the United National Front of Cambodia on one side and the government forces of the Khmer Republic on the other. Due to the strategic importance of Cambodia for both parties in the parallel Vietnam War , the troops of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) and the National Front for the Liberation of Vietnam (Viet Cong) on the one hand, and those of the United States of America and the on the other Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) involved in the fighting.

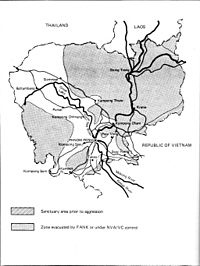

The fighting has been both prolonged and exacerbated by international interference. The troops of North Vietnam and the Viet Cong tried to maintain their supply routes and bases in eastern Cambodia. These were of great strategic importance for the fighting in southern Vietnam. The Americans tried to prevent the emergence of a new communist regime in the west of their ally South Vietnam in order to be able to guarantee this sole survival in the medium term. The Americans therefore intervened in the fighting with commandos and area bombing, and provided the Lon Nol government with both weapons and financial resources.

After five years of war, in which much of the country's economy had been destroyed and famine had weakened the population, the Khmer Rouge defeated the government forces. The war marked by many atrocities of war ended officially with the proclamation of the Democratic Kampuchea by the Khmer Rouge on April 17, 1975. Some historians today believe that the US interference in the civil war will ultimately lead to the victory of the communists and the increase in their troops 14,000 in 1970 to over 70,000 in 1975. However, this point of view is doubted by many historians. John Del Vecchio argues that before the American intervention, around 100,000 Cambodian and Vietnamese troops had already occupied two thirds of the country. Dmitry Mosyakov reports that Soviet archival sources revealed that the North Vietnamese invasion of 1970 took place at the express request of the Khmer Rouge under their chief negotiator Nuon Chea and not ostensibly to protect their own bases.

Immediately after the end of the war, the Khmer Rouge genocide followed, killing approximately one to two million people in Cambodia.

Prehistory (1965-1970)

background

During the mid-sixties, the Cambodian head of state, Prince Norodom Sihanouk , was able to prevent his country from being drawn into the chaos that had already gripped neighboring Laos and Vietnam with a neutralist policy . Both the People's Republic of China and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam certified the prince to represent a "progressive" policy. In addition, both states recognized that Sihanouk had included the left-wing opposition party Pracheachon in the government. On May 3, 1965, he finally broke off diplomatic relations with the United States because their troops fighting in Vietnam had violated the Cambodian border. This meant an end to the extensive American aid shipments for Cambodia. Instead, the country continued to turn to the Soviet Union and China, which offered extensive economic and military aid.

At the end of the 1960s, Sihanouk's balancing domestic and foreign policy began to turn more and more against him. In 1966, for example, in an agreement with the Chinese, he had to agree to the stationing of large contingents of the Vietnamese People's Army and the Viet Cong on Cambodian territory, which set up supply bases there. In addition, he had to open the port of Sihanoukville to ships from all communist countries, so that large quantities of weapons intended for Vietnam were soon delivered via this port . Through these concessions, the neutrality to which Cambodia had committed itself at the Indochina Conference was weakened further and further.

This change of course came about because Sihanouk was of the opinion that China and not the United States would be the hegemonic power over Indochina in the future and that our interests would best be protected by working together with the camp that will dominate Asia in the future - and that cooperation must begin before his power - in order to create the best possible starting point for us.

However, during the same year he allowed the openly pro-American defense minister, General Lon Nol, to strike a hard blow against activities of the Cambodian left. This subsequently smashed the Pracheachon and arrested many of its members on charges of making pacts with North Vietnam and planning an overthrow. At the same time, Sihanouk lost more and more support from the conservative groups because he was unable to get a grip on the deteriorating economic situation, triggered by a collapse in travel exports, which were increasingly sent to the Vietnamese People's Army and the Viet Cong. Since 1966, Cambodia has sold around 100,000 tons of rice to the Vietnamese People's Army, which offered the world price for this and paid in US dollars. In reality, however, the North Vietnamese government only paid a small, fixed price, which eroded Cambodia with enormous revenues. In addition, the remaining rice exports collapsed from 583,700 tons in 1965 to 199,049 tons in the following year, as the farmers on the black market were getting prices significantly higher than the prices set by the government.

The first free elections were held in Cambodia on September 11th. Through massive election fraud and electoral influence, the Conservatives managed to win 75 percent of the seats in the National Assembly. As a result, Lon Nol was elected Prime Minister and Sirik Matak , an ultra-conservative member of the royal family and avowed opponent of Sihanouk, was elected deputy. This dominance of conservatives in the government ensured that various communist groups in the countryside began to infiltrate government organizations and incite the people.

The Samlaut uprising

This polarization of Cambodian politics posed a major problem for Sihanouk himself. In order to maintain the political balance against the growing power of the conservatives, he appointed some leaders of the organizations that he had recently ordered to be a "counter-government" should critically evaluate the actions of the government to monitor Lon Nol. Lon Nol's first objective was to consolidate the shabby economy by ordering the black market for rice sales to communist forces in the country to be stopped. For this purpose soldiers were sent to the main cultivation areas to monitor the harvest. The farmers were only allowed to sell their rice to these supervisors and only received the low central price set by the government. This led to extensive unrest, the center of which was in the travel-rich Battambang province , where the communists were sometimes very influential. This was because there were many large landowners in the province and the income gap was huge.

On March 11, 1967, while Sihanouk was on a state visit to France, an open riot broke out in the Samlaut district of Battambang when angry villagers attacked a group of tax collectors. Presumably through the support and incitement of local communist cadres, the uprising quickly spread across the region. Lon Nol responded to this uprising by imposing martial law . Hundreds of civilians were killed and several villages were completely destroyed during the suppression of the uprising. As a result of this uprising, Sihanouk decided after his return at the end of March to change his previous balancing policy and ordered the arrest of Khieu Samphan , Hou Yuon and Hu Nim , the leaders of the “counter-government”. However, all three managed to flee to the north-east of the country, where the central government practically exercised no governmental power.

At the same time, he ordered the arrest of Chinese smugglers who organized the illegal rice trade and caused enormous losses to the state. In doing so, he fulfilled a longstanding demand by the conservatives. As a next step, Sihanouk dismissed Lon Nol from his office and appointed a new government made up of more left-wing politicians who were supposed to counterbalance the overwhelming power of the conservatives in the National Assembly. The acute government crisis was thus overcome, but the Samlaut uprising and its brutal suppression resulted in thousands of new recruits joining the Communist Party of Cambodia , which Sihanouk simply called Khmer Rouge (Khmer Rouge), and the name Lon Nols by and large Sections of the population became synonymous with brutal repression.

Reorganization of the communists

While the uprising of 1967 was unplanned and also surprising for the Khmer Rouge, a centrally organized, larger uprising of the people was to take place in the following year. The breakup of the Pracheachon and urban communist cells by the government apparatus had left a vacuum in the communist leadership that was filled by Pol Pot, Ieng Sary and Son Sen , leaders of the rural Maoist underground movement. These gathered new fighters and withdrew to the mountainous region in the northeast of the country, the land of the Khmer Loeu . These were a tribe that were considered backward and were largely generally hostile to both the central government and most of the inhabitants of the lowlands. The Khmer Rouge, who still had not been able to get active help from North Vietnam, used this time, when they were relatively protected from persecution by the government, to rebuild their structures and train their soldiers. Even after renewed inquiries, the North Vietnamese ignored their allies, who were mainly supported by the Chinese, and were relatively indifferent to them, a behavior that later permanently strained the relationship between the "brotherly comrades".

On January 17, 1968, the Khmer Rouge began their first planned offensive against the government. The operation, which involved no more than 4,000–5,000 fighters, was aimed at the capture of additional weapons and propaganda rather than the occupation of territory, and the Khmer Rouge soon withdrew to their original position. At the same time they established the Kampuchea Revolutionary Army as the party's armed arm. At the same time, Sihanouk had been trying for several months to make new contacts with the communists so that they might be able to participate in the government again in the future. He did so because his previous agreements with the Chinese were found to be worthless. They did not limit the North Vietnamese influence in the border area; Sihanouk even blamed her for the communist uprising in the country.

At the endeavors of Lon Nol, who had returned to the cabinet as Minister of Defense in November 1968, and other conservative politicians, Sihanouk resumed normal relations with the United States on May 11, 1969 and announced the appointment of a new National Liberation government with Lon Nol as Prime Minister. He did this "to play a new card, since the Asian communists attack us before the end of the Vietnam War." Sihanouk made the Vietnamese People's Army and the Viet Cong, which was partially occupying the east of the country, and not the Khmer Rouge for them Problems in Cambodia and suggested that withdrawal of these troops would solve much of the problems. The Americans took up this thesis and announced that such a withdrawal would solve not only Cambodia's problems, but a whole host of others in Southeast Asia .

Operation MENU

Although the US had been aware since 1966 that the Vietnamese People's Army and the Viet Cong had retreat camps and supply routes in Cambodia, President Lyndon B. Johnson decided not to bomb these areas to avoid international protests. He also feared that Prince Sihanouk might turn completely to the Communists after such an action. However, Johnson allowed reconnaissance teams from MACV-SOG , the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam Studies and Observations Group, to be sent to Cambodia to secretly gather information about the Vietnamese military infrastructure. However, the election of Richard Nixon as US President and his plan to gradually withdraw from Vietnam and Vietnamize the war changed this basic attitude. It was now planned to massively bomb and destroy the enemy's supply bases abroad in order to simplify the deployment of the ground troops. On March 18, 1969, on the secret orders of Nixon, 59 Boeing B-52 bombers bombed Base Area 353 in Cambodia, right on the Vietnamese border across from Tay Ninh Province . This was only the first in a series of air strikes on Cambodian territory that lasted until May 1970. During Operation MENU , the Air Force flew a total of 3,875 air strikes, dropping over 108,000 tons of bombs on the eastern border areas. Throughout the operation, Sihanouk did not comment on the bombing in the hope that it would actually drive the Vietnamese People's Army and the Viet Cong out of Cambodia. North Vietnam also did not issue a statement on the bombings, as they did not want to make the world public aware of the presence of North Vietnamese troops in neutral Cambodia. Therefore, the bombing of Operation MENU remained secret not only from the public but also from the US Congress until 1973.

The fall of Sihanouk

Lon Nol's takeover

While Prince Sihanouk was on another trip abroad in France, anti- Vietnamese riots broke out in Phnom Penh in March 1970 , which resulted in the representations of North Vietnam and the Viet Cong in the city being looted and destroyed. Lon Nol, who exercised sole power of government in Sihanouk's absence, did nothing to contain the unrest. On March 12, he also closed the port of Sihanoukville to all North Vietnamese transports and issued an ultimatum to all Vietnamese troops to leave the country within 72 hours. Otherwise military action by the Cambodian army can be expected.

When Sihanouk heard of the unrest, he rushed to Moscow and Beijing to ask the protective powers of the North Vietnamese to influence them and enforce their withdrawal, but this was unsuccessful. On March 18, one day after the unsuccessful expiry of the ultimatum, Lon Nol asked the National Assembly to vote on Sihanouk's future as head of state in an election. With a score of 92 to 0, Sihanouk was removed from office and Cheng Heng was appointed new President of the National Assembly, while Lon Nol was given the power of emergency legislation as Prime Minister. Sirik Matak returned to the post of Deputy Prime Minister. In a government statement, the new government stated that the change of power would take place by legal means and would therefore be lawful and therefore received recognition from most foreign governments within a short period of time. Since the change of power there have been claims that the US played a role in the overthrow of Sihanouk, but these have not yet been proven.

The prince's disempowerment was viewed with benevolence, especially among the middle class and among intellectuals, who were tired of Sihanouk's policy, which was perceived as fickle. This position was followed by the military, which viewed the resumption of financial and military aid supplies by the USA as a means of securing a living. Within days of his fall, Sihanouk, who had found asylum in Beijing, began broadcasting radio messages to Cambodia calling on the people to rebel against the usurpation. As a result, there were isolated demonstrations and riots in favor of Sihanouk, but these were largely limited to the Vietnamese-controlled area and did not pose a threat to the new government. The only more significant actions by the government opponents were the murder of Lon Nol's brother Lon Nil in Kampong Cham during a march on March 28th after his body was mutilated by the crowd; and an estimated 40,000 demonstrators march into the capital to overthrow the government. However, this was smashed by military units; there were many dead.

Massacre of the Vietnamese

Many Cambodian residents blamed the Vietnamese, the soldiers of North Vietnam and the Viet Cong as well as the Vietnamese minority in the population, for the poor situation in the country. Therefore, Lon Nol's call to recruit 10,000 volunteers to reinforce the poorly equipped, 30,000-strong army and drive the Vietnamese troops out of the country was enthusiastically received and over 70,000 volunteers volunteered. While the volunteers were being recruited, rumors surfaced that the Vietnamese People's Army was planning an offensive to conquer Phnom Penh and set up a communist regime. This led to violent attacks on the approximately 400,000 ethnic Vietnamese in Cambodia.

Lon Nol hoped to use the ethnic Vietnamese as hostages against North Vietnam in order to prevent an attack and therefore ordered the military to lock a large number of them in camps. When the arrests began, many Vietnamese were murdered at the same time. In many places the panic in front of the fifth column of the Vietnamese continued to increase, so that many Cambodians murdered their Vietnamese neighbors. The military also participated in these massacres. These massacres first became known to the world on April 15, when the bodies of over 800 murdered Vietnamese drifted across the border into South Vietnam in the Mekong .

Both North and South Vietnam and the Viet Cong sharply condemned these murders. In his subsequent apology to the South Vietnamese government, Lon Nol said

“That it was difficult to distinguish between ordinary Vietnamese and members of the Viet Cong. Therefore it is normal that the reaction of the Cambodian troops, who felt they had been betrayed, was difficult to control. "

FUNK and GRUNK

From Beijing Sihanouk announced the dissolution of the government in Phnom Penh and the planned establishment of the United National Front of Kampuchea ( Front uni national du Kampuchéa ), also known as FUNK . Sihanouk later said that he had not opted for either the American or the communist side until Lon Nol's coup, as he saw a danger in both American imperialism and Asian communism. However, Lon Nol's actions would have forced him to make a decision.

The prince then openly allied himself and his United National Front with the Khmer Rouge, the North Vietnamese, the Viet Cong and the Laotian Pathet Lao and supported their goals. On May 5, he proclaimed the United National Front and the Royal Government of the National Union of Kampuchea ( Gouvernement Royal d'Union Nationale du Kampuchéa ) or GRUNK. He made himself head of state and Penn Nouth , one of his most loyal followers, prime minister. Khieu Samphan was appointed Deputy Prime Minister and Defense Minister, as well as Chief Commander of the GRUNK Armed Forces. However, these were more subject to Pol Pot than to Khieu. Hu Nim became Minister of Information, and Hou Yuon was given the Ministry of the Interior, Municipal Reforms and Cooperation. Since Khieu Samphan and other leaders of the armed resistance were still inside the country, the GRUNK did not see itself as a government in exile. However, apart from a visit by the prince to the liberated areas and Angkor Wat in March 1973, Sihanouk and many of his followers stayed in China throughout the war.

He saw the alliance with the communists mainly as a short-term marriage of convenience to get revenge on those who in his eyes had betrayed him. However, the Khmer Rouge benefited significantly more from this alliance, as it gave them a kind of legitimation in large parts of the population. Many loyal citizens therefore supported the FUNK cause. Sihanouk's statement that the communist troops would behave much better towards the civilian population than the Americans, who had bombed the country indiscriminately, drove more people into the arms of FUNK. However, their cause was supported most strongly by Lon Nol himself, when he abolished the federal monarchy and proclaimed the centralized Khmer republic.

Spread of the war (1970–1971)

Enemy sides

Immediately after the coup it was not Lon Nol's intention to wage war against the hostile groups within Cambodia. Rather, he tried to win the population over in a peaceful way. In addition, he turned to the international community and the United Nations to gain support for his government and complained that Cambodia was neutral

"Foreign forces, whatever camp they belong to"

would hurt. However, since he continued to insist on his country's neutrality, international support for him was rather weak.

When the first fighting broke out shortly after the coup, it quickly became clear that both sides were not prepared for a major war. The government troops, now called the Khmer National Armed Forces ( Forces Armées Nationales Khmères , FANK), were reinforced in the months after the fall of Sihanouk by thousands of volunteers, mainly from the country's urban regions. As FANK immediately accepted almost all of the volunteers as recruits, it soon became apparent that they were unable to equip and manage such enormous numbers of people effectively. Later, when the fighting required more and more men and at the same time the high losses had to be compensated, the training of new recruits was shortened more and more, so that the soldiers' lack of tactical skills represented one of their greatest problems until the FANK collapsed.

In the period around 1974–1975, FANK's forces grew from around 100,000 to officially 250,000 soldiers. However, due to the officers' falsified pay lists and ongoing desertions, the real strength may have been only around 180,000 men. The USA delivered equipment, ammunition and other supplies to FANK via the Military Equipment Delivery Team, Cambodia (MEDTC). The unit, consisting of a total of 113 officers and men, arrived in Phnom Penh in the course of 1971. Officially, it was under the command of USPACOM , Admiral John S. McCain . The general stance of the Nixon administration can be summed up with the advice of National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger to the MEDTC's first field commander, Colonel Jonathan Ladd:

"Don't think of victory; just keep it alive. "

“Do not think of victory; just keep it alive. "

Despite this rather apathetic attitude by the government, Admiral McCain repeatedly advocated at the Pentagon for more weapons, equipment and personnel for what he called his war .

Another problem facing government troops was the widespread corruption in the FANK officer corps. So many soldiers only existed on paper and the officers struck off their pay. In addition, many officers withheld the scarce rations for their own consumption, while their husbands often starved. In some cases, weapons and equipment were even sold either on the black market or directly to the enemy. An American commission of inquiry also found that the Cambodian officer corps was strategically inexperienced and neither knew how to organize a large army nor was aware of the deadly threats it was facing. Another obstacle to a functioning chain of command was given by Lon Nol himself, who repeatedly interfered in the work of the general staff in order to command operations down to battalion level himself and a coordination between army, air force and navy, which in his opinion would have been dangerous can prevent.

At first, morale within the army was also very good among normal soldiers, but soon suffered from chronic undersupply and low wages, from which the soldiers usually had to buy food and medicine for themselves. Since there was only pay for the soldiers themselves and the families were not supported by the state, many followed the men and thus represented a further burden on the supply and organization in the combat zone. This poorly powerful army stood with the Khmer Rouge a guerrilla army, which was supported by the Vietnamese People's Army, which at the time was considered the best infantry army in the world. The Vietnamese supported the restructuring of the armed forces of the Khmer Rouge, decided at an Indochinese meeting in Conghua , China in April 1970, and helped equip the new troops when the Khmer Rouge increased the number of its soldiers from 15,000 in 1970 to 35,000-40,000 Year 1972 increased. Subsequently, the so-called Khmerization of the conflict began and the fight against Lon Nol's republic was completely handed over to the Cambodian forces.

The build-up of communist forces during the conflict can be divided into three phases. In the first phase from 1970 to 1972 they served more as auxiliary troops of the Vietnamese People's Army, which took over a large part of the organization. After the Cambodians were seen as being able to wage the war independently, the Khmer Rouge formed various units at battalion or regimental level, which could operate as independently as possible, but also in association. During this period from 1972 to around mid-1974, there was also increasing alienation between the Khmer Rouge and Prince Sihanouk and his allies, as the Khmer Rouge began to promote the forced collectivization of agriculture in the areas they had conquered. From mid-1974 until the end of the war, the communists increased their number of troops so much that they organized their units at divisional level and laid the foundation for a radical transformation of the country they aimed for.

The Cambodia Campaign

On April 29, 1970, South Vietnamese and American troops began the so-called Cambodia Campaign . This limited operation was started because of fear that communist forces would quickly overrun Cambodia and overthrow Lon Nol's government. In addition, the government in Washington hoped to be able to solve other problems with it. By destroying the Vietnamese supply bases in the Vietnamese-Cambodian border area, they wanted to cover their own flank during the planned American retreat from Vietnam. In addition, the operation was supposed to be a test run for the planned Vietnamization of the war and send a signal to the North Vietnamese government that Nixon would not allow its influence to expand any further. Although the operation was started to support the government of Lon Nol, the latter was unaware of it and was just as surprised by the invasion of Vietnamese-American troops as the communists. He only found out about it when the commander of the American military mission in Phnom Penh informed him of the troop movements. However, he had only heard of the invasion from the radio.

After a short time, the troops reported that large quantities of enemy supplies had been found and destroyed, but even larger quantities could already be brought to safety in the interior of the country and that one would therefore have to advance deeper into Cambodia. After 30 days, American forces began to withdraw from the operation and hand over control to the Vietnamese and Republican Cambodians. Republican General Sak Sutsakhan later said that this left a void in the Allied command structure and army forces that neither of the two remaining armies could ever have closed.

As early as the day the Cambodia campaign began, the North Vietnamese forces started an offensive against the FANK forces in response to this, in order to protect their bases inland and to expand the area they controlled. This happened because it was expected that the supply stores near the border would be lost quickly. By June they had conquered the entire north-eastern third of the country from FANK and were gradually handing it over to their Cambodian allies. At the same time, the Khmer Rouge, independent of the North Vietnamese, had conquered smaller areas in the south and south-west of the country.

Operation Chenla II

On the night of January 21, 1971, Vietnamese troops raided Pochentong airport , where a large part of the FANK air force was stationed. The majority of the aircraft were destroyed in this raid. However, since the majority of these were obsolete machines of Soviet and American design and these were quickly replaced by more modern American machines as a result of the attack, this incident can be regarded as a lucky break. However, he delayed a planned FANK offensive by several months and Lon Nol suffered a stroke two weeks later . He was flown to Hawaii for treatment and was able to return to Cambodia two months later.

It was not until August 20 that FANK Operation Chenla II , its first major offensive in the war, could launch. The aim was to free a secure connection to Kompong Thom and to purge it of enemy forces. The second largest city under Republican control had been surrounded by enemy forces for over a year and could only be reached by air. The operation was able to reach its goal quickly and repel the enemy forces, but a counter-offensive by the North Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge in November and December was able to recapture the lost area, destroying the majority of the FANK troops and destroying large amounts of material and supplies. As a result of this failure, the offensive in the war finally passed into the hands of the communist forces.

Decline of the Khmer Republic (1972-1975)

fight to survive

Between 1972 and 1974, FANK's forces were mainly occupied with holding the territory under their control. Smaller operations were only carried out to defend the rice-growing areas in the northwest and along the Mekong as well as the overland road to the Republic of Vietnam and to create space for themselves. The tactic of the Khmer Rouge was to narrow these supply lines more and more and thus to enclose Phnom Penh more and more. The success of this tactic ensured that the FANK troops were more and more dispersed and isolated and joint operations were hardly possible.

American support for the Republican forces consisted mainly of massive air support from bombers and ground attack aircraft. The Cambodia campaign had already taken place under a massive bomber umbrella. These air strikes continued after the campaign ended as an Operation Freedom Deal to disrupt communist lines and supply depots. However, this operation was only authorized to support the Cambodia campaign , which is why the continued support of the FANK troops was kept secret from the American Congress and the public. A post-war support mission officer in Phnom Penh said that until 1973, when Operation Freedom Deal was suspended, the Mekong valley was so littered with bomb craters that it resembled the surface of the moon.

On March 10, 1972, shortly before the Constituent Assembly could pass the new constitution, Lon Nol announced its dissolution and forced Cheng Heng, head of state since the fall of Sihanouk, to transfer his office to him. On the second anniversary of the coup, Lon Nol announced his new office, but held the post of prime minister and defense minister at the same time.

On June 4th, he was elected the first President of the Khmer Republic in an apparently fraudulent election. By the constitution ratified on April 30th and still changed by Lon Nol, the parties that had been founded since the proclamation of the republic were largely disempowered and de facto insignificant.

In January 1973, the Republican side once again hoped that the war would soon end when the Paris Peace Agreement ended the war in South Vietnam and Laos. As a result, on January 29th, Lon Nol unilaterally announced a ceasefire for the whole country. All American air operations over Cambodia were stopped in order not to destroy the possibility of peace. However, the Khmer Rouge ignored this offer of peace and started new offensive operations. By March, losses, desertions and low volunteer numbers had reduced the manpower of FANK to such an extent that Lon Nol introduced conscription . In April, however, communist troops were able to penetrate into the suburbs of Phnom Penh for the first time. However, several American air strikes were able to force them to retreat and inflicted heavy losses on them as they retreated into the country.

When Operation Freedom Deal was finally halted on August 15, 1973, a total of 250,000 tons of bombs had been dropped on Cambodia in the course of its course, 82,000 of them in the last 45 days alone. Since Operation MENU started , a total of 539,129 tons of bombs had been dropped on the land.

Communist change

Until about the turn of the year from 1972 to 1973, the conflict, both in Cambodia itself and abroad, was considered to be one between foreign powers in which the nature of the country's inhabitants had not changed. During 1973, however, many Cambodians had the impression that the Khmer Rouge became more and more fanatical, as they immediately turned down any offer of peace and did not care in the least about their own losses or civilian casualties in the fighting.

Rumors of the communists' brutal policies and goals soon spread to Phnom Penh, giving many people an inkling of what would happen after their victory. There were stories of entire villages being sent and those who disobeyed or even asked questions were executed. There was talk of the prohibition of religious practices and the murder of monks and priests. The emergence of such stories coincided with the withdrawal of the North Vietnamese troops from Cambodia, which had apparently prevented the Khmer Rouge from implementing their political and social goals.

The leadership of the Khmer Rouge was almost unknown to the general public. It was also only referred to by its followers as peap prey ( forest army ). It has long been unknown that the Communist Party was part of GRUNK. Over time, however, they were increasingly able to take control of this. They had already created their own liberated areas beforehand . In these she was mostly only known as Angka ( The Organization ). During 1973 the most radical supporters around Pol Pot and Son Sen took over the leadership of the Khmer Rouge. They believed that Cambodia was going through a total social revolution and that everything old had to be destroyed. Under this leadership, the Khmer Rouge began to be more and more suspicious of the North Vietnamese, suspecting them of wanting to establish an Indochinese federation under the domination of Vietnam. In addition to racial ideological motives, the close ties of the Khmer Rouge to China played a role, while the North Vietnamese turned more to the Soviet Union, which, for example, still recognized Lon Nol's government as the legitimate one. After the Paris Peace Agreement, the North Vietnamese government cut the supply lines of the Khmer Rouge in the hope of forcing them to a ceasefire and preventing a regime loyal to China on the western flank. As a result, a wave of purges ran through the leadership of the Khmer Rouge in the course of the year and many cadres who were considered to be Hanoi loyal were executed. These executions were ordered by Pol Pot himself.

After the communists had stopped working directly with Prince Sihanouk's faction earlier, they began to take an increasingly hostile attitude towards him and his supporters and made it clear to the people in their area of influence that supporting the prince would mean their liquidation. Although Sihanouk continued to enjoy the protection of the Chinese, Ieng Sary and Khieu Samphan openly expressed their contempt for the Chinese when he promoted the GRUNK cause on trips abroad. Sihanouk was well aware of this hostility and told Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci in June: "If they [the Khmer Rouge] suck me up, they'll spit me out like a cherry stone." By the end of 1973 the communists had removed all of the prince's supporters from the ranks of the GRUNK and had them and many of his supporters executed in the ranks of the armed forces. Shortly after Christmas, when the Khmer Rouge was preparing for a final offensive, Sihanouk told a French diplomat that his hopes for moderate socialism in Cambodia based on the model of Yugoslavia were no longer achievable and that Stalinist Albania was more likely to be the model for the upcoming government is to be seen.

The case of Phnom Penh

When the Khmer Rouge started their offensive on January 1, 1975 to conquer the besieged Cambodian capital, the remnants of the republic were already in collapse. The economy lay on the ground and supplies could only be transported safely over water and through the air. The available rice harvest had fallen to a quarter of its pre-war value and freshwater fish, which normally represented one of the main sources of protein for the population, were almost no longer available. The food prices had meanwhile risen to 20 times the pre-war value and the unemployment figures were no longer even recorded.

Phnom Penh, which had a population of 600,000 before the war, had now grown to over two million people due to the constant influx of refugees. The already poor supply situation was exacerbated in February when the Khmer Rouge conquered the banks of the Mekong on both sides of the city, thereby reducing supplies even further. The Americans set up an airlift to supply the city, but this turned out to be extremely risky as the communists soon came within firing range of the city's airfields and took them under almost permanent fire.

The fighting was fought with extreme severity as the FANK soldiers expected the worst and fought to the end due to the many rumors of the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge in the event of capture. In the last week of March about 40,000 communist fighters took up positions around Phnom Penh, facing only half as many poorly equipped and half-starved Republican soldiers.

In this situation, Lon Nol resigned from all positions and left the country on April 1st. He hoped that a compromise peace could still be found when he was out of the country and had no more power. Saukam Khoy took over the office of President of the Republic from him. The last attempts by the USA to push through a peace agreement with the involvement of Prince Sihanouk failed. When a resumption of air support for the republic was also rejected in a vote in the US Congress, morale in the besieged city collapsed completely.

On April 12, the United States began evacuating its embassy by helicopter in Operation Eagle Pull , without notifying the Republican government . Among the total of 276 evacuees, in addition to the American embassy staff, there were many members of the Cambodian government with their families who had fled to the embassy when they learned of the evacuation, including President Saukam Khoy. A total of 82 Americans, 159 Cambodians and 35 third-country nationals were flown out. Although the American ambassador had offered to evacuate them, Prince Sisowath Sirik Matak , Long Boret , Lon Non (a brother of Lon Nol) and many other members of the former government of Lon Nol, decided not to leave Cambodia. They were determined to share the fate of their people. Although the Khmer Rouge had promised to spare former members of the government, most of them perished in the following days under partly unexplained circumstances.

After Saukam Khoy's flight, a seven-member military council was formed under General Sak Sutsakhan, who exercised governmental power in the republic. On April 15, however, the last fortified defensive position around the city collapsed and was overrun. In the early hours of April 17, the Military Council decided to move its seat of government to the northwestern province of Oddar Meanchey . At ten o'clock in the morning, General Mey Si Chan announced on the radio that all FANK troops should stop fighting as negotiations on the surrender of Phnom Penh were ongoing. This ended the Cambodian civil war and the Khmer Rouge proclaimed the Democratic Kampuchea . Almost immediately, they began forcing all residents to leave the city and driving them into the countryside, which later led to the Khmer Rouge genocide.

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Heuveline: The Demographic Analysis of Mortality in Cambodia. 2001.

- ^ Sliwinski: Le Génocide Khmer Rouge: Une Analyze Démographique. 1995.

- ^ Banister and Johnson: After the Nightmare: The Population of Cambodia. 1993.

- ↑ Philip Nobile: The Crime of Cambodia: Shawcross on Kissinger's Memoirs . In: New York Magazine . November 5, 1979 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- ^ The Economist, February 26, 1983.

- ^ Washington Post, April 23, 1985.

- ↑ Mosyakov: The Khmer Rouge and the Vietnamese Communists: A History of Their Relations as told in the Soviet Archives. 2006.

- ↑ Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, pp. 54-58.

- ↑ a b Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 83.

- ↑ a b Lipsman and Doyle: Fighting for Time: 1969-1970. 1983, p. 127.

- ^ Duiker: Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954-1975. 2002, p. 465 ff.

- ↑ a b Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 85.

- ↑ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, pp. 153-156.

- ^ Osborne: Before Kampuchea: Preludes to Tragedy. 1984, p. 187.

- ^ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, p. 157.

- ↑ a b Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 86.

- ^ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, pp. 164f.

- ^ Osborne: Before Kampuchea: Preludes to Tragedy. 1984, p. 192.

- ↑ Lipsman and Doyle: Fighting for Time: 1969-1970. 1983, p. 130.

- ^ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, p. 165.

- ^ A b Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, p. 166.

- ↑ Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 87.

- ^ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, p. 128.

- ^ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, p. 141.

- ^ Deac: Road to the Killing Fields: The Cambodian War of 1970-1975. 2000, p. 55.

- ↑ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, pp. 174-176.

- ↑ Sutsakahn: The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse. 1989, p. 32.

- ↑ Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 89.

- ↑ Lipsman and Doyle: Fighting for Time: 1969-1970. 1983, p. 130.

- ↑ Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 90.

- ↑ Lipsman and Doyle: Fighting for Time: 1969-1970. 1983, p. 140.

- ↑ Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 88.

- ^ Karnow: Vietnam: A History. 1983, p. 590.

- ↑ Nalty: Air War Over South Vietnam: 1968-1975. 2000, pp. 127-133.

- ^ Deac: Road to the Killing Fields: The Cambodian War of 1970-1975. 2000, p. 56f.

- ↑ Shawcross: Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. 1979, p. 118.

- ↑ Lipsman and Doyle: Fighting for Time: 1969-1970. 1983, p. 142.

- ↑ Stutsakhan: The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse. 1989, p. 42.

- ↑ Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 90.

- ↑ Lipsman and Doyle: Fighting for Time: 1969-1970. 1983, p. 143.

- ↑ Shawcross: Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. 1979, pp. 112-122.

- ↑ Shawcross: Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. 1979, p. 126.

- ↑ a b c d e f Lipsman and Doyle: Fighting for Time: 1969-1970. 1983, p. 144.

- ↑ Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 90.

- ^ Deac: Road to the Killing Fields: The Cambodian War of 1970-1975. 2000, p. 69.

- ^ Deac: Road to the Killing Fields: The Cambodian War of 1970-1975. 2000, p. 71.

- ^ Deac: Road to the Killing Fields: The Cambodian War of 1970-1975. 2000, p. 75.

- ↑ Lipsman and Doyle: Fighting for Time: 1969-1970. 1983, p. 145.

- ^ Fighting for Time: 1969-1970. 1983, p. 146.

- ^ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, pp. 228f.

- ^ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, p. 200.

- ^ Osborne: Sihanouk: Prince of Light, Prince of Darkness. 1994, pp. 214-218

- ^ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, p. 201.

- ^ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, p. 202.

- ^ Fighting for Time: 1969-1970. 1983, p. 146.

- ^ Sutsakhan and Test: The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse. 1989, p. 48.

- ^ Deac: Road to the Killing Fields: The Cambodian War of 1970-1975. 2000, p. 172.

- ^ Sutsakhan and Test: The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse. 1989, p. 39.

- ↑ Nalty: Air War Over South Vietnam: 1968-1975. 2000, p. 276.

- ↑ Shawcross: Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. 1979, p. 190.

- ↑ Shawcross: Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. 1979, p. 169.

- ↑ Shawcross: Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. 1979, p. 169 and 191.

- ↑ Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 108.

- ↑ Shawcross: Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. 1979, pp. 313-315.

- ^ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, p. 205.

- ↑ Shaw: The Cambodian Campaign: The 1970 Offensive and America's Vietnam War. 2005, p. 137.

- ↑ a b Sutsakhan and Test: The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse. 1989, p. 89.

- ↑ Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 108.

- ^ Kinnard: The War Managers. 2007, p. 67.

- ^ Sutsakhan and Test: The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse. 1989, pp. 26-27.

- ^ Sutsakhan and Test: The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse. 1989, pp. 78-82.

- ^ Karnow: Vietnam: A History. 1983, p. 607.

- ^ Karnow: Vietnam: A History. 1983, p. 608.

- ^ Deac: Road to the Killing Fields: The Cambodian War of 1970-1975. 2000, p. 79.

- ^ Sutsakhan and Test: The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse. 1989, p. 174.

- ^ Deac: Road to the Killing Fields: The Cambodian War of 1970-1975. 2000, p. 72.

- ^ Sutsakhan and Test: The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse. 1989, p. 32.

- ^ Sutsakhan and Test: The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse. 1989, p. 79.

- ↑ Nalty: Air War Over South Vietnam: 1968-1975. 2000, p. 199.

- ^ Pike et al .: War in the Shadows. 1991, p. 146.

- ^ Pike et al .: War in the Shadows. 1991, p. 149.

- ↑ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, pp. 222f.

- ↑ Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 100.

- ↑ Morrocco: Rain of Fire: Air War, 1969-1973. 1985, p. 172.

- ↑ Shawcross: Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. 1979, p. 297.

- ↑ a b Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 106.

- ↑ a b c d e Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 107.

- ^ Deac: Road to the Killing Fields: The Cambodian War of 1970-1975. 2000, p. 68.

- ↑ Shawcross: Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. 1979, p. 281.

- ^ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, p. 211.

- ^ Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. 1993, p. 231.

- ^ Osborne: Before Kampuchea: Preludes to Tragedy. 1984, p. 224.

- ↑ Shawcross: Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. 1979, p. 321.

- ↑ Shawcross: Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. 1979, p. 343.

- ↑ Lipsman and White: The False Peace: 1972-1974. 1985, p. 119.

- ^ Snepp: Decent Interval: An Insider's Account of Saigon's Indecent End Told by the CIA's Chief Strategy Analyst in Vietnam. 1977, p. 279.

- ^ Deac: Road to the Killing Fields: The Cambodian War of 1970-1975. 2000, p. 218.

- ↑ Isaacs and Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. 1987, p. 111.

- ^ Ponchaud: Cambodia: Year Zero. 1978, p. 7.

literature

- Judith Banister and Paige Johnson: After the Nightmare: The Population of Cambodia. in Genocide and Democracy in Cambodia: The Khmer Rouge, the United Nations and the International Community. Yale University South East Asia Studies, New Haven 1993, ISBN 0-938692-49-6 .

- David P. Chandler: The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. Yale University Press, 1993, ISBN 0-300-05752-0 .

- Wilfred P. Deac: Road to the Killing Fields: The Cambodian War of 1970-1975. Texas A&M University Press, 2000, ISBN 1-58544-054-X .

- Clark Dougan, David Fulghum: The Fall of the South. Boston Publishing Company, Boston 1985, ISBN 0-939526-16-6 .

- William J. Duiker , Military History Institute of Vietnam: Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence 2002, ISBN 0-7006-1175-4 .

- Patrick Heuveline: The Demographic Analysis of Mortality in Cambodia. in Forced Migration and Mortality. National Academies Press, Washington DC 2001, ISBN 0-309-07334-0 .

- Arnold R. Isaacs and Gordon Hardy: Pawns of War: Cambodia and Laos. Boston Publishing Company, Boston 1987, ISBN 0-939526-24-7 .

- Stanley Karnow: Vietnam: A History. Viking Press, 1983, ISBN 0-670-74604-5 .

- Douglas Kinnard: The War Managers. Naval Institute Press, 2007, ISBN 1-59114-437-X .

- Samuel Lipsman and Edward Doyle et al .: Fighting for Time: 1969-1970. Boston Publishing, Boston 1983, ISBN 0-939526-07-7 .

- Samuel Lipsman and Stephen Weiss: The False Peace: 1972–1974. Boston Publishing Company, Boston 1985, ISBN 0-939526-15-8 .

- Stephen Morris: Why Vietnam invaded Cambodia: Political Culture and the Causes of War. Stanford University Press, Stanford 1999, ISBN 0-8047-3049-0 .

- John Morrocco: Rain of Fire: Air War, 1969-1973. Boston Publishing Company, Boston 1985, ISBN 0-939526-14-X .

- Dmitry Mosyakov: The Khmer Rouge and the Vietnamese Communists: A History of their Relations as told in the Soviet Archives. in Genocide in Cambodia and Rwanda. Transaction Publishers, 2006, ISBN 1-4128-0515-5 .

- Bernard C. Nalty: Air War Over South Vietnam: 1968-1975. Air Force History and Museums Program, Washington DC 2000.

- Milton E. Osborne: Before Kampuchea: Preludes to Tragedy. Allen & Unwin, 1984, ISBN 0-86861-633-8 .

- Milton E. Osborne: Sihanouk: Prince of Light, Prince of Darkness. University of Hawaii Press, 1994, ISBN 0-8248-1638-2 .

- Douglas Pike, James W. Gibson, John Morrocco, Rod Paschall, John Prados, Benjamin F. Schemmer, and Shelby Stanton: War in the Shadows. Boston Publishing Company, Boston 1991.

- François Ponchaud: Cambodia: Year Zero. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1978, ISBN 0-03-040306-5 .

- John M. Shaw: The Cambodian Campaign: The 1970 Offensive and America's Vietnam War. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence 2005, ISBN 0-7006-1405-2 .

- William Shawcross: Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. Simon & Schuster, 1979, ISBN 0-671-23070-0 .

- Marek Śliwiński: Le Génocide Khmer Rouge: Une Analyze Démographique. L'Harmattan, 1995, ISBN 2-7384-3525-4 .

- Frank Snepp: Decent Interval: An Insider's Account of Saigon's Indecent End Told by the CIA's Chief Strategy Analyst in Vietnam. Random House, 1977, ISBN 0-394-40743-1 .

- Sak Sutsakahn, Warren A. Test: The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse. Dalley Book Service, 1989, ISBN 0-923135-13-8 .

- John Tully: A short history of Cambodia: From Empire to Survival. Allen & Unwin, 2005, ISBN 1-74114-763-8 .