Pole pot

Pol Pot (* probably May 19, 1925 or 1928 as Saloth Sar in the Kompong Thom province , Cambodia ; † April 15, 1998 in Anlong Veng ) was a communist Cambodian politician and dictator (1975–1979) and until 1997 as "Brother No. . 1 “ the political and military leader of the Khmer Rouge .

He was born as Saloth Sar and came into contact with communism while studying abroad in Paris . Back at home, he joined the conspiratorial Communist Party of Indochina (KPI), which was controlled by the Việt Minh , and worked as a teacher. In 1962 he became the first secretary of what would later become the Communist Party of Kampuchea (KPK) and fled political persecution by Lon Nol to the border area with Vietnam the following year , where he finally gave up his name and was referred to as "Brother Number One" or "Uncle Secretary" . For the next seven years, Pol Pot lived underground and was heavily influenced by Maoism through a trip to China . During the Cambodian civil war , the communist militias led by Pol Pot became the Khmer Rouge , which was able to attract more and more recruits due to the dissatisfaction of the rural population in particular with the massive American bombing of Operation MENU .

In April 1975, the Khmer Rouge captured Phnom Penh and deported the urban population as supposed enemies of the revolution to the countryside, where they had to do forced labor as new people in the workers and peasants state . Still hidden behind the front organization angkar padevat , also known as Angka, the communists proclaimed the Democratic Kampuchea in January 1976 and elected Pol Pot as prime minister. The radical collectivism and political cleansing under his rule led to the establishment of torture prisons such as Tuol Sleng and the Killing Fields . Constant skirmishes with Vietnam eventually resulted in an open war that ended in the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia and forced Pol Pot into exile in Thailand . His rule, known as Stone Age Communism , caused the genocide in Cambodia , in which, according to estimates, between 750,000 and more than 2 million of a total population of around 8 million were killed as a result of execution , forced labor, hunger and inadequate medical care. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal examined to date committed under Pol Pot crime behind which historians class struggle but also racist motives suspect and categorized the persecution of minorities as genocide .

Mostly from Thailand, Pol Pot waged a guerrilla war against the Vietnamese occupying power and the puppet state of the People's Republic of Kampuchea, which it installed and supported . After the Vietnamese withdrew in 1989, the Paris Peace Treaty was concluded in October 1991 , ending the second civil war. Pol Pot was replaced as a leading figure by Ta Mok in June 1997 and died probably of suicide on April 15, 1998 in Anlong Veng .

Life

Date of birth

Saloth Sar's year of birth has not been established beyond doubt. The records of the colonial authorities of French Indochina show May 19, 1928 as the date of birth; his siblings give the year 1925. More recent biographies do not consider the official registrations of that time to be reliable sources, because subsequent entries with incorrect data were common at the time, especially in rural areas.

Early life

Saloth Sar's parents Pen Saloth and Sok Nem were Khmer and lived in the village of Prek Sbauv in the immediate vicinity of the provincial capital, Kampong Thom . Saloth Sar had seven or eight siblings, depending on the source. The family was considered wealthy. The father was a rice farmer with 9 hectares of land and draft animals . Although there were Chinese ancestors in the paternal line of ancestors, traditions such as the Chinese New Year or Qingming Festival were not cultivated, but lived in the Khmer style. Saloth Sar was called “Sar” because of his light skin color ( sar is Khmer for 'white'). Parental upbringing was based on Theravada morality and in a Buddhist temple in Kampong Thom, which the family visited regularly, Sar learned the first letters of the Khmer script .

Sar's family was closely linked to the Cambodian royal family in several ways. His father's sister was employed in the royal household in Phnom Penh. In the 1920s, their daughter Meak was a concubine of Crown Prince Sisowath Monivong , who was King of Cambodia from 1927. Together they had a son born in 1926. On Meaks mediation, Sars brother Loth Suong received a position as an officer in the royal palace; his daughter later also became a concubine of the king.

Sar was sent to the capital by his parents when he was a child, where he first lived with Suong and Meak. He followed his brother with it. According to one source it was "1931 or 1932", another source gives it the year 1934. It is doubtful whether the reason for this, as is sometimes alleged, was due to financial distress of the parents. Other sources assume that the parents wanted their sons to get an education in Phnom Penh and were able to finance it with their own resources.

During this time he lived for a few months as a novice in the Buddhist monastery Wat Botum, where he learned to read and write the Khmer language.

From 1936 Sar attended the Catholic school École Miche near the royal palace. Most of the schoolmates were children of French colonial officials and Catholic Vietnamese , who at the time, along with the Chinese, dominated the economy and trade in Phnom Penh and the rest of the country.

Sar was considered a mediocre student. In 1941 and 1942, Sar fell through the final exams of the École Miche ; It was not until 1943 that he successfully passed it on the third attempt. He then tried to train at the Lycée Preah Sisowath , the oldest secondary school in Cambodia, but did not pass the entrance exam. However, as one of 20 Cambodian boys, he was given the opportunity to attend a middle school named after Norodom Sihanouk in the eastern Cambodian provincial town of Kampong Cham , which the French colonial authorities had newly founded. Sar belonged to the first year here. The lessons were given in French and followed classical educational content, so Sar learned to play the violin, among other things. After successfully completing secondary school, Sar was admitted to the Lycée Preah Sisowath , according to a source, in the summer of 1947 , which he had to leave after only a year after he had failed an intermediate examination in the summer of 1948. He then began to learn the profession of carpenter at an École technique in northern Phnom Penh.

During the years of his training, Sar established friendships that lasted for decades. Classmates at the École Miche included Hu Nim , Khieu Samphan and Lon Non, Lon Nol's younger brother . After coming to power in 1975, Hu Nim and Khieu Samphan were among the top officials of the Khmer Rouge. During his training as a carpenter, he came into contact with members of less privileged social classes who were marginalized by the French and the traditional elite. There he got to know, among others, Ieng Sary , who later followed him to Paris and became one of the highest-ranking cadres of the Khmer Rouge as “Brother No. 3”. From this and from other personal interrelationships, retrospective considerations derived the assessment that the Khmer Rouge was structured like a clan.

When parties were allowed to be founded in Cambodia in accordance with an agreement between Paris and Phnom Penh from 1946 onwards, Sar and Sary were involved in the 1947 election campaign for the Democratic Party of the National Assembly led by Prince Sisowath Yuthevong, which was dissolved by Sihanouk only a year later. The Democratic Party mainly advocated the idea of national independence and a strong orientation towards traditional values and was popular with students, teachers, employees and monks. In 1948, Sar received a scholarship to study technology abroad in Paris. It remains unclear whether this was because the Democratic Party, which controls the Ministry of Education, was made aware of Sar by Sary, or whether professions such as radio electronics, tailor, carpenter and photographer were promoted by the nationalists in order to break the Vietnamese dominance. In August 1949, Sar set out by sea to France.

Studied in Paris

Arrived in Marseille at the end of September 1949, he attended courses on radio electronics at the university in Paris . At that time he was living in the Indochinese house in the Cité Internationale Universitaire de Paris . In addition to Sary, who arrived in Paris the following year, two formative acquaintances for Sar during this period were the Cambodian nationalists Thiounn Mumm and Ken Vannsak. In the summer of 1950 he served for four weeks with 17 other Cambodians and French students in a Socialist Brigade in Yugoslavia . In 1952, possibly at Mumm's initiative, he became a member of the Parti communiste français (PCF). He underwent while studying any tests and was therefore late 1952 expelled . The communist circle of Sar under the umbrella of the PCF met at Vannsak's apartment and had only Cambodian members who were Khmer. Through Vannsak, who had attended an international youth congress in East Berlin in August 1951 , Sar first learned of the existence of a Khmer communist resistance group, the Khmer People's Revolutionary Party (RVPK). This was founded in June 1951 as the sub-organization responsible for Cambodia of the still clandestine Communist Party of Indochina (KPI), which was largely controlled by the publicly operating Communist Party of Vietnam .

During his stay in France, Sar traveled to Poitiers to see Sơn Ngọc Thành, who had been under house arrest there for six years . Sơn was Cambodia's prime minister for a short time in 1945 and was arrested after the re-establishment of French colonial rule over Cambodia. In mid-1951, he was released from house arrest and returned to Cambodia, where a large crowd gave him a triumphant welcome. In March 1952, Thành went underground and joined an anti-French, non-communist guerrilla militia. After he had failed to persuade the Communist and Pro-Vietnamese resistance groups to join forces with him against the French colonial power, he became a marginal figure in the independence movement until the end of 1952. Nonetheless, Sihanouk and his French mentors were so worried by Thành's popularity, his immersion in the armed resistance and the electoral victory of the Democratic Party against the conservatives around Yem Sambaur and Lon Nol the previous year that in June 1952 the Democratic Cabinet was ousted and the National Assembly dissolved has been; Paris increased its troops in Phnom Penh. Sar dealt with these events in his first known political writing Monarchy or Democracy? a, which appeared in Paris in the summer of 1952 in the Khmer- language student newspaper Khmer Nisut , and condemned Sihanouk as an absolute monarch who served imperialism and was an enemy of the common people and Buddhist monks. Sar had Monarchy or Democracy? published under the pseudonym Khmer daom (German: "original Khmer").

Indochinese Communist Party and teaching at Chamraon Vichea

In January 1953 Sar returned to Cambodia and lived for the first time with a brother in Phnom Penh. Through another brother named Chhay, he made contacts with armed non-Communist anti-French independence movements around Sơn Ngọc Thành and Norodom Chantaraingsey . However, he chose not to join any of these groups. Instead, he asked Pham Van Ba, the local contact person of the sub-organization of the KPI responsible for Cambodia, to join the party, claiming membership in the PCF as a qualification. After checking Sars' information about Hanoi in Paris, which took a few weeks, he became a member of the KPI. Unlike the RVPK, which had more than 1,000 members by 1954, the KPI still operated covertly and was heavily controlled from Vietnam. In August 1953, Sar reached eastern Cambodia and served on the border with Vietnam in the command post of a militia dominated by the Việt Minh , later in their propaganda staff and in the cadre school. Here he met the former monk Tou Samouth , who became his mentor and, with Sơn Ngọc Thành, had set up the 5,000-strong Khmer Issarak militia commanded by the RVPK . Here he made the acquaintance of Vorn Vet , who became one of his companions in the following years. Since in this phase of the Indochina War, shortly before and during the Indochina Conference, the fighting decreased, France released the countries into independence and the non-communist independence fighters laid down their arms, Sar waited for the results of the conference without having gained combat experience with the Việt Minh Geneva . When there, unlike in Laos and Vietnam, the prospect of free elections for the next year, but no refuge areas for the communist militias, many communists went into exile in North Vietnam , including Tou Samouth and Sơn Ngọc Thành. Sar soon returned to the capital to continue to work in the service of the KPI. Vorn Vet followed him until October 1954 at the latest. His assignment probably included preparations for the elections, the Pracheachon party as a front organization, contacts with the radical wing of the To take up the Democratic Party and influence it in the interests of the KPI.

Sar's college friends Thiounn Mumm and Ken Vannsak, who had introduced him to communism in Paris, lived in Cambodia again from August 1954 and were in contact with Sar. In January 1955, Shichau, Vannsak and Mumm took power in an internal party rebellion in the central executive committee of the Democratic Party, although Sar's role remains unclear. In the period leading up to the election, Sar likely wrote articles for the Sammaki , a radical newspaper published by his brother Chhay. Before the elections, Sihanouk, backed by a broad alliance of different camps, exerted great political pressure on his political opponents. He abdicated after a heavily manipulated referendum, which resulted in 95% support for his royal path to independence , and declared his father Norodom Suramarit king. Freed in this way from the binding court ceremony , Sihanouk founded Sangkum Reastr Niyum (German: Socialist People's Community), a political organization that all employees of the state administration had to join, and suppressed the free press. Nevertheless, the front organization Pracheachon and the Democratic Party were able to successfully hold large events, so that Sihanouk had Vannsak and many other Democrats arrested and Mumm forced into exile in France, while Sar remained undisturbed. In the 1955 elections, Sangkum Reastr Niyum finally won all seats in the National Assembly with more than 80% of the vote and, under the leadership of Sihanouk, determined the policy for the next 15 years.

In view of the new political situation, Sar was initially without a specific mandate. In July 1956 he married his girlfriend Khieu Ponnary . With her sister, she had been the first Cambodian to earn a degree . She had met Sar in 1951 in France, where her younger sister Thirith married his friend Ieng Sary. At the time of their wedding, Ponnary was teaching Cambodian literature at the Lycée Sisowath , while Sar took up his position as a teacher at the capital's private school Chamraon Vichea (German: progressive knowledge) for French, history, geography and civics . In spite of his well-known communist convictions, he gained a high reputation here, especially among his students. Sar's lessons were considered precise and understandable and, unusual for the traditional teacher-student relationship at the time, allowed questions that he answered helpfully. Chamraon Vichea was a private college for students who, like Sar himself, had not passed the entrance examination to a state lycée . It was likely created with funding from Lon Nol and Prince Norodom Chantaraingsey to counterbalance the rival Sons of Cambodia college established by the Democratic Party in December 1952 and which was under its control. At this time Sar already had several identities and used the code name Pol for Pracheachon . He also worked undercover for the KPI and organized the protection of their party leaders Tou Samouth and Sieu Heng. In much of his secret activities during these years he worked with Nuon Chea , later known as "Brother Number Two". Like Sar, he had been a member of the KPI since 1951. The extent to which the RVPK continued to exist at this time is unclear. In 1957, sister-in-law Thirith and friend Ieng Sary, who became a lecturer at the Sons of Cambodia University, returned to Cambodia from Paris and lived with Sar and Ponnary for a while.

At that time, mainly pupils and teachers, students who had radicalized themselves abroad, and urban workers from the still very narrow industrial sector were among the members of the KPI, fewer farmers and former militias in the countryside. The leadership, to which Sar belonged alongside Hou Yuon and Ieng Sary, managed to increase the number of members of their party between 1956 and 1960. At that time, the KPI was successfully pursuing a united front strategy. Some of its secretive members, such as Khieu Samphan and Hu Nim , publicly supported Sihanouk, who led Cambodia into the Non-Aligned Movement . From 1959 Sihanouk was increasingly obsessed with the idea that murder plots from Thailand and South Vietnam, both of which had granted Thành exile, were going on against him. He stopped his sharp anti-communist rhetoric and Hou Yuon became deputy minister.

When King Norodom Suramarit died in April 1960 , there was a dispute over the succession to the throne and Sihanouk again took action against the communists. He had Samphan arrested in August 1960, his newspaper closed, the front organization Pracheachon smashed in 1962 and its members sentenced to life imprisonment. In the overall organization IPC, which was dominated by Hanoi, on the other hand, after the partition of Vietnam, the support of the National Front for the liberation of South Vietnam was in the foreground, as confirmed by the Third Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam in early September 1960. Left on their own and exposed to acute persecution, two weeks later, according to Sar and Nuon Chea, the first and, according to other sources, the second party conference of the Cambodian communists took place in a smaller building on the Cambodian railroad. A total of 21 rural and urban representatives elected Sar Tou Samouth as the first party secretary. Sơn Ngọc Minh from Hanoi, Nuon Chea, Keo Meas , So Phim and Ieng Sary were elected to the Central Executive Committee of the Kampuchea Labor Party (APK). The APK acted like a nameless secret organization and still largely followed Hanoi's will.

In July 1962, Tou Samouth disappeared with fate still unknown to this day. The backgrounds are assessed differently in the literature. The historian Ben Kiernan believes that a generation change in the party should be brought about and that Sar was involved in Tou Samouth's elimination. David P. Chandler, on the other hand, reports of a murder by security forces or possible betrayal by Sieu Heng. Sar became the first secretary of the APK and Nuon Chea his deputy. In addition to his official teaching activities, Sar, like Hou You and Khieu Samphan, held secret seminars, mostly in front of monks and students, in order to attract young people to the organization and to stir up general dissatisfaction with Sihanouk. There he convincingly portrayed the utopia of a new society in which there are no prices and taxes because everyone has a job. He described people who lived at the expense of others as an evil to be overcome, and he headed the royal court, in whose milieu he himself had spent his youth. When students at a Lycée in Siem Reap demonstrated against police violence and Sangkum Reastr Niyum in early 1963 , and protests broke out across the country, Lon Nol made a list of 34 people to be eliminated, including Sar. Sar was able to flee in time and go to a Vietnamese military camp on the border with Cambodia. Since that time he did not use his name at all, merged his identity with the party and was mostly referred to as "Brother Number One" or "Uncle Secretary".

Beginnings of the Khmer Rouge

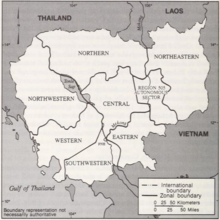

For the next seven years, Pol Pot was on the run and lived with Ieng Sary and other members of the Cambodian Communist Central Committee in constantly changing makeshift camps in the east and northeast of the country, as well as in North Vietnam and China. There they were almost exclusively among themselves, except for radio reception and the occasional party courier from Phnom Penh, they were cut off from the rest of the world. Until 1969, a few hundred students followed them underground. Pot was forbidden to leave the first accommodation, the so-called Office 100 of the Viet Cong on the border with Vietnam in Kampong Cham . For the next two years, Pot was almost entirely dependent on outside help, with many of his supporters at the time later being viewed by Pot as enemies and executed in the S-21 torture prison. In conversations with one another or with younger party comrades who saw Pot as a teacher, in firm belief in their future power after the overdue revolution they developed dreamy utopias that had less and less to do with reality. At that time, Sihanouk was the first to use the name Khmer Rouge for the group. From June 1965, Pot was in exile in North Vietnam for 9 months. During this time he presented himself as the successor to Tou Mamouth and communicated with Hanoi the increasingly important role of the Cambodian communists in the Vietnam War. The events during this stay were described in the polemic Livre noir , published twelve years later, and cited as the reason for the break with Vietnam; Pol Pot is likely to have written this writing and generally adhered to the external facts. Accordingly, Lê Duẩn , the second man after Hồ Chí Minh, massively criticized the independent political line of the Cambodian communists. Furthermore, they had to sign documents in Vietnamese language obliging the Khmer Rouge to recognize the primacy of the revolution in South Vietnam, to wait for its success and until then to stand as a united front behind the anti-American Sihanouk. Despite the indignation expressed in the livre noir , Pot externally gave in to Vietnamese pressure and refrained from starting an armed uprising of his own in Cambodia.

The trip to China in 1966 following his stay in Vietnam had a great influence on Pot . Here, inspired by the prevailing Maoism and the beginning of the Cultural Revolution , Pot adopted Mao's views on independent revolution, permanent class struggle and voluntarism and saw in the big leap forward a model for Cambodia. From then on he judged the Vietnamese dominance negatively. Pot experienced novel methods of the Chinese Communist Party at this time, such as the partial evacuation of cities, the storm attack on economic problems and a rank army that was taken over by the Khmer Rouge. During this time he made friends with Kang Sheng , who pointed out to him the importance of exposing and destroying hidden enemies of the party. In addition to Kang Sheng, Pot was probably received in Beijing by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping , who were responsible for Chinese foreign policy with Zhou Enlai at the time . For China at that time the alliance with Sihanouk was more important than the APK matter, which is why they advised Pot to stand behind the prince for the time being. As with Yugoslavia in 1950, Pot impressed China with the high level of social mobilization, especially in the cities, and the comparatively modern post-revolutionary society, which stood in stark contrast to the war-torn Vietnam and the rural Cambodia. In addition to the Mao Bible , the rapid expansion of which Pot could observe in China and whose emphasis on the revolutionary potential of the simple rural population he was able to understand and transfer to Cambodia, a commemorative publication by Lin Biao from September 1965 influenced his political views. In this defense of Maoist ideas it was emphasized, among other things, that in the Third World the communist revolutions should take place independently and not controlled by larger socialist countries, and that capitalist cities should be isolated and defeated by revolutionary-controlled rural areas. Not only Pol Pot, but also other revolutionary movements in Thailand, Bolivia and the Philippines subsequently invoked Lin Biao's ideas.

In 1965, Sihanouk decided to sever diplomatic relations with America and let the Vietnamese People's Army and National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam operate on the Sihanouk Trail , which complemented the Ho Chi Minh Trail . In the following year, the election of Lon Nol as prime minister not only led to a threatening deterioration in domestic politics, but also to the attack of the Second Indochina War on Cambodian territory. After Sukarno was unable to prevent the massacres of the Communists in Indonesia from 1965 to 1966 , concerns grew that the Sihanouk constellation against Lon Nol would be in the same situation. On his return to Cambodia in September 1966, Pot therefore had to relocate his camp to the remote Ratanakiri province , to Office 104 . Later, the entire Office 100 from Kampong Cham fled there, bringing the party leadership together in one place. They lived here among semi-nomadic mountain peoples, the Khmer Loeu , who were hostile to the government themselves and who in large numbers could be won over to the goals of the communists. Here, as later elsewhere, many were convinced by Pol Pot's argument that Cambodia's problems stemmed from an insurmountable urban-rural conflict that had to be resolved in favor of the rural population. In September 1966 the WPK was renamed the Communist Party of Kampuchea (KPK). Kiernan sees this as a distancing from the Party of the Working People of Vietnam and a rapprochement with the Communist Party of China .

During a long trip abroad from Sihanouk, Prime Minister Lon Nol militarily prevented the rural population from supplying the Viet Cong in Cambodia. This led to the Samlaut uprising in Battambang province in March 1967 , which was largely carried out by farmers and spread to neighboring provinces. As a counter-reaction, Sihanouk, who has since returned, smashed the organizational structures of the communists in the cities. Pot therefore set up a leadership seminar for the KPK at the end of 1967. The decision was to develop primarily politically and to protect the party leadership with militias, and to leave the local leaders to decide whether and how they could take part in the fighting. On January 17, 1968, there was one of several attacks by communist militias on army units, which the Khmer Rouge celebrated later than their birth. The situation in Cambodia worsened after the Tet offensive , Sihanouk's foreign policy turnaround with the resumption of diplomatic relations with the United States in mid-1969 failed, the military under Lon Nol fought more and more with the Viet Cong, other Vietnamese militias and isolated resistance groups Communists. At the same time, Richard Nixon ordered the top secret Operation MENU and thus a massive area bombardment of the Viet Cong's operational areas in Cambodia with B-52 bombers . All of these events drove more recruits to the Khmer Rouge, so that by the end of 1970 they had over 4,000 fighters. Kiernan sees the American bombing of Cambodia, in which 540,000 tons of bombs were dropped mostly on rural areas between 1969-73, the most important single factor for the successful mass mobilization of the Khmer Rouge. Pol Pot's exact whereabouts from early 1968 to late 1969, when he traveled to Vietnam for the second time, is unknown. While fleeing through Cambodia, he probably took part in several makeshift camps in building up the growing party and in the political education of its members.

Cambodian Civil War

It is certain that Pol Pot resided in North Vietnam from the end of 1969. In the Livre Noir , Pot reports on a falling out with the Vietnamese Communist Party over the primacy of war in South Vietnam, which the Cambodian communists should first serve. His later behavior rather suggests that he continued to follow Hanoi's line. The situation changed abruptly when the strictly anti-communist Lon Nol took advantage of the increasingly anti-Vietnamese popular mood given the effects of the Vietnam War. In March 1970 he deposed Sihanouk while he was on a trip abroad, which started the Cambodian civil war . Thereafter, Lon Nol had the National Assembly grant him special powers, called on the Viet Cong to leave the country within two days, and proclaimed the Khmer Republic . Probably together with Phạm Văn gemeinsamng , Pot arrived in Beijing on March 21, 1970, two days after Prince Sihanouk, who was living here in exile, since China was one of the few countries that had not recognized the Khmer Republic. The presence of Pot was kept secret from Sihanouk. Since the united front with Sihanouk no longer existed and Lon Nol fueled the conflict, the Viet Cong and parts of the North Vietnamese army fought together with the Cambodian communists against Phnom Penh.

The Viet Cong and Hanoi claimed leadership and initiative in the Cambodian civil war against the Khmer Rouge and quickly recruited troops for the Front Uni National du Kampuchéa (FUNK) from the rural population under the banner of Prince Sihanouk . On the other hand, roles were sometimes reversed when Vietnamese forces were harassed and fled to areas controlled by the Cambodian communists. At that time, the front organization of the KPK, angkar padevat (German: Revolutionary Organization), had almost 3,000 men and women armed in smaller combat units that were spread across the forests of the provinces of Kampong Speu , Kampot , Battambang, Kratie and in the northeast. In April 1970, Pot set out from Hanoi via the Ho Chi Minh Trail to Cambodia. When he reached Office 102 after six weeks , he sent Ieng Sary to Hanoi as a liaison officer , where Keo Meas was already doing a similar job. In the meantime, during the Cambodian Campaign from April to July 1970, American and South Vietnamese ground troops had moved into Cambodia, while the anti-Vietnamese atmosphere under Lon Nol had led to ethnically motivated massacres and many volunteers for the Cambodian army.

Against this background, the Khmer Rouge relocated their headquarters to Phnom Santuk in the Kampong Thom province, as the central command of the Vietnamese was located here, although according to Livre noir the entire leadership around Pot was tired of the dominance and dependence on the Viet Cong and North Vietnam until mid-1971. Although there were occasional small skirmishes between the Viet Cong and Cambodian communists, the war against Lon Nol in 1971-72 was mostly waged by Vietnamese and Cambodians under Vietnamese command. As part of the Operation Chenla II offensive, begun in August 1971 by Lon Nol, the FUNK forces were able to decisively repel the government troops until December of the same year, with the Vietnamese units in particular proving to be strong. Lon Nol was on the defensive from then on; his influence was mainly limited to the cities, which were filled with more and more war refugees. From then on, Pot and the rest of the party leadership were convinced that they could win the Cambodian civil war alone and without Vietnamese support. Pot increased the degree of organization of angkar padevat and designated a special administrative zone south and west of the capital. Vorn Vet was assigned this area, in which party schools were set up and cadres and fighters were trained. In the writings on indoctrination that were widespread there, it was repeatedly emphasized that simple peasants, members of the lower middle class and workers as party cadres would determine the future of the country and would make the capitalist and feudal classes disappear.

In March 1972, Beijing announced that Pot was the military chief of staff in the FUNK and that he only determined the strategy and left the tactical decisions to the military on the ground. After the Treaty of Paris and contrary to Hanoi's requests , Pol Pot decided not to join the armistice between the United States, South and North Vietnam, and to continue the FUNK fight from January 1973 without Vietnamese support. On the one hand, the KPK viewed the Paris Treaty as a betrayal of the common struggle, on the other hand, the return to a purely political organization under the regime of Lon Nol was inconceivable for them. As a result, the party removed all Hanoi cadres from the organization, and some of these Vietnamese cadres were executed. When the Vietnamese troops withdrew, there were first skirmishes with the Khmer Rouge.

In the areas controlled by the KPK, restrictive social and educational programs were implemented. Buddhist religious practices and other cultural traditions, such as the semi-nomadism and animism of the mountain peoples, were suppressed, young people were separated from their families and committed to party work in groups. The population was forced to wear uniform, the farmers had to form cooperatives. In addition, there were forced resettlements under the Khmer Rouge and, from May 20, 1973, the collectivization of agriculture and the ban on private property, which further increased the rural exodus.

The Americans, concentrated on the last remaining theater of war in Indochina, launched massive air strikes on the Khmer Rouge in March 1973 with the intensified follow-up operation to Operation MENU, Operation Freedom Deal . Up to August 1973 250,000 tons of bombs were dropped, 10,000 Khmer Rouge and between 30,000 and 250,000 civilians were killed. These attacks had devastating effects on the countryside and civil life came to a standstill. The Operation Freedom Deal led the one hand, that part of the population radicalized and enlisted by the Khmer Rouge, on the other hand, many people fled into the areas under control of the troops of Lon Nol cities. The KPK viewed the rural refugees as traitors, which increased their already existing hostility towards the cities. In May 1973, Pot ordered the first storm attack on Phnom Penh. This failed because of American air raids and in August 1973 because of the rainy season. The Khmer Rouge had suffered the worst casualties in the civil war to date. While Operation Freedom Deal was ravaging the country, Pot and Sihanouk met for the first time. Pol Pot remained hidden, because when the prince entered Cambodia he was greeted by a delegation from Khieu Samphan, Hou Youn and Hu Nim introduced themselves to him in the style of a front organization as the decision-makers of FUNK in the Cambodian civil war. It was not until two days later that Sihanouk near Angkor met the pot, which had remained shyly in the background for the entire gathering, without realizing its significance.

At the beginning of 1974 there was the second storm attack on Phnom Penh, the population of which had meanwhile grown to over two million and which had not been defended by the American Air Force since August 1973. Because of the unexpectedly strong resistance of the government troops under Lon Nol, the second attack on the capital was broken off with heavy losses in April 1974, with neither side taking any more prisoners. Nevertheless, they succeeded in cutting off the city more and more from the outside world and, for example , interrupting the transport routes to Sihanoukville . In late 1974, Pot met with Chou Chet, Party Secretary for the Southwest, to coordinate the plans for the third assault on Phnom Penh and to monitor their implementation in some combat units themselves. Before the end of 1974, Phnom Penh had no road connection to the outside world. At the end of January 1975, the Khmer Rouge relocated Chinese sea mines in the Mekong to make river transport to Phnom Penh impossible.

In February 1975, when the fall of Phnom Penh was foreseeable, the Central Committee of the KPK decided the complete evacuation of Phnom Penh and all other cities as well as the deportation of the population there; in the eyes of the Khmer Rouge, the city dwellers, including many members of the Chinese and Vietnamese minorities, were enemies of the revolution and the refugees were traitors. They should be brought to the country in order to eliminate them as opposition and to use them in the future workers-and-peasant state by means of forced labor in agriculture . After Phnom Penh could no longer be reached by air at the end of March 1975, Lon Nol resigned at the beginning of April and fled into exile, which effectively ended the Khmer Republic. A short time later, the American embassy was evacuated, and on April 12 the embassy staff and their relatives were flown out by helicopter in Operation Eagle Pull . Finally, on April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge invaded Phnom Penh. To have humiliated America as a great power and the fact that this happened before Operation Frequent Wind in Saigon was a success for the Khmer Rouge, which they almost exclusively attributed to themselves.

The Pol Pot Regime

In power

With the invasion of Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouge turned the radical, Stone Age Communist utopias of the Central Committee of the KPK around Brother Number One, devised in the isolation of the underground, into reality. The first step was the deportation of the city population. The residents of the capital, i.e. allen khmang (German: enemies) and nay tun (German: capitalists), were ordered to leave the city within one day. In contrast to the smallholders, who as simple people initially remained largely undisturbed, the townspeople were seen overnight as new people or people of April 17th, many thousands of whom died during the resettlement in the next few weeks. In less than a week, the entire population was also abducted from all other cities in the former Khmer Republic, including Pot's older brother and other close relatives, which he took no account of. When Pol Pot arrived in Phnom Penh on April 23, 1975, he was thus entering a ghost town . He had the city secured militarily, executed a large number of the prisoners of war from Lon Nol's army and set up the new headquarters in a train station.

In May 1975, the Mayaguez Incident, the final armed conflict between United States troops and the Khmer Rouge occurred . In the same month, the Khmer Rouge conquered some Vietnamese islands in the Gulf of Thailand without triggering any significant military backlash. During this phase, Pot visited North Vietnam, China and North Korea and worked with the Central Committee on the constitution for the new republic. In Beijing, his visit was kept secret from the public. Mao pledged $ 1 billion in financial support to Pol Pot, while the first of probably 1,000 Chinese technicians and skilled workers to help the Khmer Rouge arrived in Cambodia. Prince Sihanouk, who was officially still the leading figure of FUNK, was only allowed to move from Pot to Cambodia in September 1975 under Chinese pressure.

According to reports from the few contemporary witnesses who survived the massive political cleansing of the Killing Fields, among them Heng Samrin , a meeting of the civil and military leadership of Cambodia took place in the capital from 20 to 24 May 1975, for which no minutes are received are. Here the permanent evacuation of all cities, the prohibition of money, the market and Buddhism as well as probably the sending of troops to the Vietnamese border was decided. According to contemporary witnesses, further requirements of the party leadership were the execution of all executives of the Lon Nol regime and the nationwide consolidation of villages into agricultural cooperatives, although this measure was formulated later, according to other statements. The party magazine Tung Padevat (translated: "Revolutionary Flag") announced in August 1975 that the various cooperatives in a village, which usually comprised 15-30 families, should be merged into one. In 1976, people were banned from preparing food in private households and they were obliged to take their meals in communal canteens. In addition, the meeting in May 1975 decided to expel the ethnic Vietnamese: Pol Pot, who spoke before the meeting on the second day, stressed that Cambodia could not tolerate a Vietnamese minority.

In July 1975, the population was divided into three groups: people with full rights , candidates, and landfills . The people with full rights were simple people loyal to the political line , who had no relationship among the people of April 17th or the already executed victims of the Pol Pot regime and who showed convincing zeal for work. Most of the dumped people were people from April 17, that is, citizens who had been “relocated” from the city to the countryside, and simple people with a burdened biography. The candidates formed an intermediate group. This included, for example, people who did not come from simple farming families and therefore had deficits in socio-economic status . In principle, it was possible for candidates to join the group of people with full rights by serving in the armed forces or working for the cause of the revolution .

The KPK, whose front organization was still angkar padevat , took more than a year to set up an administration, its decisions being kept secret and the people behind the aliases hidden. In the minutes of the meetings of the Central Committee from October 1975 to June 1976 that have been received, an allocation of tasks is initially recorded in the form of a cabinet. On October 9, 1975, eleven men and two women were assigned proto-ministerial responsibilities:

- Pol Pot as Comrade Secretary , Brother Number One: Defense,

- Nuon Chea as Comrade Deputy Secretary , Brother Number Two : Party Organization and Education,

- Ieng Sary: foreign affairs,

- Son Sen : secret service and the military general staff,

- Non Suon: agriculture,

- Chhim Samauk as Chief of Staff of the Prime Minister,

- Front Vet: Economy,

- Ieng Thirit: Social Affairs.

The wives of Sen and Sary performed other functions. By 1978, Pol Pot had five of the 13 named people executed. Outwardly, the leading figure of the revolution was still Prince Sihanouk. He had Beijing's support, which is why the Khmer Rouge could not part with him. That changed in January 1976 when Sihanouk's most important supporter, Zhou Enlai , died. Deeply disturbed by the events in Cambodia, Sihanouk submitted his resignation to angkar padevat in March 1976 . Pot detested Sihanouk because it symbolized the exact opposite of his ideal of the life of simple peasants and workers, but on the other hand he wanted to keep it as a patriotic identification symbol in the country where he had it under control. The FUNK therefore confirmed his resignation on April 12, 1976 and the prince lived under house arrest from then on. Pot's leadership also concerned the fact that large parts of Cambodia were still under the control of Vietnamese troops.

Democratic Kampuchea

In January 1976 the National Liberation Front (FUNK) was dissolved and the Democratic Kampuchea was proclaimed. The constitution stipulated a comprehensive collectivization of the economy that deeply affected the realities of life and equated Angka with the interests of the people. In April 1976, an election for the assembly of the people's representatives was held, mainly with the aim of reassuring foreign countries. While the people of April 17th had no right to vote, the 250 candidates were all nominated by angkar padevat and not listed by province but by professional group. The turnout remained low because, according to a deputy, only workers had the opportunity to vote, while farmers were not allowed to vote. Pol Pot first appeared under that name as "Rubber Plantation Worker" and was elected Prime Minister. After that, the assembly of people's representatives decided to dissolve it for an indefinite period. Until then, he had used both Pol and Pot as aliases. Pol Pot has no independent meaning, unlike the revolutionary battle names given by the other members of the Central Committee. The Assembly of People's Representatives met in mid-April 1976, confirmed the government of Democratic Kampuchea, and adjourned indefinitely. The election of Pol Pot as Prime Minister was announced on the radio on April 14th.

As members of the government, Pol Pot and the others feared assassinations and coup attempts even more than before, which is why the Central Committee always acted in secrecy, closely guarded. From July 1976, minutes or other documents were no longer drawn up at the meetings of the Central Committee. Two priorities can be identified up to 1977, the implementation of the four-year plan for building socialism in all fields , which Pol Pot presented to the Central Committee on August 21, 1976, and the political cleansing of the republic and party. Much of the killings were carried out at the party's interrogation center, Tuol Sleng . The tensions with Vietnam that came to a head up to the war led Pol Pot to try even more quickly to implement the four-year plan and to free himself from his enemies.

The four-year plan was based on Pol Pot's four basic principles of collectivism , self-sufficiency , the will to revolution and empowerment of the poor, which should pave the way to socialism. The aim was to increase travel exports to such an extent that the trade surplus could be used to finance the import of goods and goods to build up their own industry and the associated proletariat. The ideal was heavy industry , which was symbolically included in the state emblem, completely independent of the fact that there are no ore deposits in Cambodia. This export orientation stood in contrast to the complete prohibition of markets, money and private property inside. Rice as the only significant export good was almost metaphysically charged by Pol Pot and propagated as the way to liberate the Cambodian farmers from their poverty. Typically the targets set by brother number one in the four-year plan were utopian and amounted to 3 tons per hectare for rice, although the yield in the year before the outbreak of the Cambodian civil war had been less than 1 tons. In the provinces of Battambang and Pursat , there was now a storm attack on agriculture, with the help of a million displaced city dwellers by 1980, 140,000 hectares of forest should be cleared for rice cultivation. In the following two years tens of thousands of them died of starvation and starvation. The expectations of the rice harvest, which border on wishful thinking, especially in the north-west with its million slave laborers, were not fulfilled and from the beginning of 1977 malnutrition increasingly turned to starvation. Many of the survivors later reported a common aphorism of the party cadres about the urban forced laborers, the new people : “Keeping [you] is no gain. Losing [you] is not a loss. "

Although Pol Pot and other members of the Central Committee were teachers, not farmers, education was not part of the four-year plan. Only a few primary schools and no middle school until 1978 were established, and nothing was done to literate the rural population. The lessons were mainly oral and conveyed party content, while in history the time before the revolution was completely ignored. The four-year plan had no use for culture beyond revolutionary schooling and education, such as in the form of songs or poems, and rejected all pre-revolutionary traditions.

In September 1976 there was a leadership crisis among the Khmer Rouge. On September 18, Pol Pot wrote a public commemorative pamphlet for the late Mao Zedong , in which he announced for the first time that Cambodia was being ruled by a Marxist-Leninist organization. Only two days later, the party secretary for the Northeast, Ney Saran, was arrested, and a little later the party leader, Keo Meas. Both were later murdered in Tuol Sleng, probably because Pol Pot wanted to eliminate the older generation. At the same time, Pol Pot announced his resignation for health reasons on Radio Phnom Penh. This was probably another maneuver to confuse foreigners on the one hand and to lure internal party opponents out of cover on the other, because only a few days later he was back in office. A sharp dispute in the party revolved around the question of whether 1951, when the party was still completely controlled by Vietnam, or 1960 should be celebrated as the founding year of the KPK. Although Pol Pot had intended to present the four-year plan at the anniversary celebration for the founding of the party on September 30, 1976 and possibly educate the public about the real ruling party behind angkar padevat , he canceled the celebration. From then on, according to his speeches and the documents received from Tuol Sleng, he was preoccupied with the party's political cleansing and relations with Vietnam.

Killing Fields

While there is little written information about the government decisions of the Khmer Rouge, they made sure that their mass murders in killing fields such as Choeung Ek and Tuol Sleng are well documented by the tortured inmates' written "confessions". The "conspiracies" that led to the interrogations and murders, which Pol Pot cited as justification, were similar to those of the show trials during the Great Terror and the campaign against rootless cosmopolitans of 1948–53. Kaing Guek Eav and the other camp leaders of the Killing Fields sent the reports, which contained the "confessions" of the tortured and subsequently executed victims, via Son Sen to the party headquarters K-1. There the documents were compared with one another, “conspiratorial” networks with Vietnam or the CIA were identified and their members were executed in the killing fields, which resulted in further “confessions”. After soldiers from the former Lon Nol regime and Cambodians with connections to North Vietnam were initially the victims, the political cleansing began in May 1976 within the Khmer Rouge, which was initially directed against the party cadres in the east of the country, led by So Phim had advocated a more lenient stance on Vietnam. In December 1976 Pol Pot held a leadership seminar for the party. In contrast to previous occasions of this kind, his speeches now lacked triumphalism about a successful revolution. He spoke of enemies and traitors as microbes within the party who, if left unchecked, threatened the very existence of the KPK. For protection, the party should remain hidden from the public. For crop failures, he blamed the displaced urban population, who directed production in some areas because no party cadres were available. In order to put pressure on the party cadres in the east, which are supposedly more susceptible to treason, and to be able to replace them with communists from the southwest, the leadership decided at this meeting for the eastern administrative zone to set particularly high standards for rice production. In this region in particular, ethnic cleansing took place , to which the Muslim Cham fell victim. The course for this policy had already been set in 1973, as documents of the Central Committee of the KPK show.

From January 1977 high party officials such as Hu Nim and a large part of the party's intelligentsia were brought to the killing fields. This wave of purges particularly affected the northern administrative zone, where the murdered party cadres were replaced by Khmer Rouge from other regions. After Pol Pot's visit to the Northwest Administrative Zone, the local party leadership began to be annihilated here, too, replaced by members of the Southwest who were under the control of Ta Mok . Until mid-1977, the Killing Fields, which developed a momentum of their own that could hardly be stopped as a result of the "conspiracies" discovered, became an essential part of Pol Pot's government work. In the years 1977-78 "conspirators" in the immediate vicinity of Pol Pot and other leaders were exposed and murdered along with their families. This, in turn, intensified the fears of persecution of Pol Pot, who from then on pursued little more than purifying the party, while the base of the KPK was becoming increasingly narrow due to the mass murders. He lived with his staff, many of them members of the hill tribes, in constantly changing accommodations, shied away from public appearances and, for fear of assassinations, only attended party meetings when all participants went through a gun check. He put even supposed errors such as a failure of the electricity or water supply in his office in a “conspiratorial” context and had the relevant supervisory staff killed. Overall, analysis of the Tuol Sleng confessions suggests that three quarters of the victims were abducted to the killing fields not because of their activities but because of their personal connections.

War with Vietnam

Since the Khmer Rouge came to power, there have been armed conflicts with Vietnam. This was not only due to the delayed withdrawal of the Viet Cong, especially from Cambodia's northeast, but also to the nationalism of the regime, concerns about the loss of autonomy due to Hanoi's dominance in Indochina and disputes over the maritime border between the two states, which I discovered shortly before Natural gas reserves in this area have increased. Pol Pot viewed the rapprochement between Laos and Vietnam, which culminated in a friendship treaty in July 1977, with great concern. From the end of 1976, military support from Beijing, which was increasingly anti-Vietnamese, ensured that the Khmer Rouge became more capable of fighting and that, at the beginning of 1977, increased attacks on Vietnam, especially in the south-west, could be dared. At the same time, the Central Committee instructed the local party cadres to hand over all ethnic Vietnamese, including those married to Cambodians, to the security forces who had to kill them in the killing fields. More and more people fled the genocide in Cambodia, so that in October 1977 60,000 refugees sought protection in Vietnam and almost 250,000 in Thailand.

In March 1977 the soldiers employed in agriculture in eastern Cambodia were withdrawn and used in the attack on two cities in the Vietnamese province of Kiên Giang . Pol Pot turned down a ceasefire offer from Hanoi in June 1977. In August 1977, artillery began to bombard Vietnamese territory ; the Khmer Rouge repeatedly invaded Tây Ninh province , where they killed or abducted numerous civilians. Under pressure from Beijing and possibly Pyongyang , Pol Pot exposed the KPK as the real power behind the front organization angkar padevat in a five-hour speech on Radio Phnom Penh, recorded on September 27, 1977 and broadcast three days later on the party's 17th anniversary. One focus of the speech was the presentation of the party work and its underlying strategies from 1960 to 1975 as well as the core ideas of Pol Pot such as collectivization and liberation of the simple rural population from poverty and supposed oppression. In the end, he went into the post-revolutionary phase since 1975 and said that deficiencies that had occurred since then were due to reactionary elements, which made up 2% of the population.

On September 28, 1977, Pol Pot reached Beijing, where he was received by Hua Guofeng and Deng Xiaoping . The photographs of this event were the first publicly available recordings of Pol Pot and subsequently enabled experts to identify him as Saloth Sar. One of the motives for this trip and the public appearance was to signal to Vietnam that China was firmly on the side of Cambodia in view of the increasing tensions between Hanoi and Beijing. In addition, Pol Pot wanted to give his regime a human face, as accusations were raised abroad over human rights violations and the famine in Cambodia. On October 4th, he and his delegation traveled on to North Korea. On this occasion, the North Korean media were the first in the world to send a short biography of Pol Pot, which was never broadcast in the Democratic Kampuchea , so that he would remain hidden from his people. During this trip, Vietnamese troops marched into Cambodia in retaliation for the attacks on Tây Ninh, although this military conflict remained hidden from the outside world.

On December 25, 1977, the Central Committee under Pol Pot decided to break off diplomatic relations with Vietnam. At this point in time, the Vietnamese troops were already up to 20 km within Cambodia. Less than two weeks later, the Vietnamese troops withdrew behind the border, which the propaganda in Cambodia celebrated as a historic victory. Shortly thereafter, Pol Pot visited the Eastern Administrative Zone, where Hanoi's troops had penetrated deepest into Cambodia. He congratulated the military leaders there on their courage to fight and, back in Phnom Penh, ordered their murder. Contrary to what Vietnam intended, the invasion and retreat did not make the Cambodian leadership more willing to negotiate, but radicalized their course even further. On January 17, 1978, Pol Pot emphasized in a speech that Cambodia would defeat and destroy Vietnam just as the United States did in 1975 and that this was also the firm belief of the rest of the world. Until February 1978, Khmer Rouge raided locations in Vietnam repeatedly, leaving scorched earth behind and massacring the population. By June, three quarters of a million Vietnamese had fled these attacks from the border areas.

With the start of the Vietnamese offensive in November 1977, Pol Pot allowed selected foreigners to enter the previously completely isolated country in order to gain foreign policy support against Hanoi. Official visiting delegations from Burma, Malaysia, Romania and Scandinavia as well as cadres of pro-Chinese Marxist-Leninist parties from Australia, Belgium, Denmark, France, Italy and Japan came to the country and were sometimes greeted by him personally. In March 1978, Yugoslav press representatives were the first foreign journalists to visit Democratic Kampuchea. The program of the visit also included a brief interview with Pol Pot, one of the very few during his reign. The interview with the Yugoslav television team was part of a short biography. Pol Pot hid his origins, which is relatively privileged due to his family ties to the palace, and his true name.

Other measures taken by Phnom Penh in view of the Vietnamese offensive, besides the continuation of the mass murders and the collection of “confessions” in the killing fields, were easing the situation against the people of April 17th . Elementary schools teaching reading, writing and simple mathematics were established in the municipalities, the slave laborers were given more free time, and the division into people with full rights , candidates and landfills was abolished in May 1978. In addition, all Cambodians who allegedly had connections to foreign intelligence services or Lon Nol and Sihanouk before the founding of the Democratic Kampuchea were amnestied . Hundreds of well-educated Cambodians had come to the country since 1976 to join the Khmer Rouge. Many of them, and all of them from the United States, died in the killing fields or what would later become the Kampong Cham labor camp. 15 of them were released and started a technical faculty under the direction of Thion Mumm . It remains unclear whether the Khmer Rouge wanted to unite the country against Vietnam with these measures or whether opponents of the regime were to be lured out of cover.

Despite these amnesties, the number of victims increased in the killing fields, whose death mechanism had developed a life of its own. In Tuol Sleng, more people were killed in the first six months of 1978 than in the entire previous year. In the second half of the year, massive political cleansing took place in the eastern and northeastern administrative zones, affecting party cadres, soldiers and their families who were held responsible for the advance of the Vietnamese armed forces. Leading party cadres executed during 1978 included Vorn Vet, Chou Chet and Muol Sambath, who had been Pot's close confidants since the 1950s. So Phim escaped deportation to the Killing Fields by suicide, whereupon all 700 residents of his village were murdered. Pol Pot's motives for these executions are not clear, possibly the decisive factors were different strategic views or the conscious maintenance of political instability in order to convert the country from a socialist to a communist form of society with a perpetual revolution , as envisaged by Maoism.

Hundreds of thousands of Cambodians died when the population was abducted from the eastern administrative areas in the direction of the Vietnamese armed forces. As the state import lists from mid-1978 show, the regime decided to import almost 250 tons of blue fabric at that time. The blue kramas produced from it were distributed to the unsuspecting Cambodians deported from the east in order to mark them as death row inmates. Pol Pot chose the color blue possibly because of his childhood in the Royal Palace, where there were blue-uniformed cleaning columns made up of prisoners, or because of his brigade deployment in the Socialist Republic of Croatia . At the time of the German occupation, the Serbs were forced to wear blue armbands there. The Cambodians marked in this way were then gradually killed at their destinations and were subordinate to the new people in terms of their status as “Khmer with a Vietnamese spirit” . Estimates of the number of victims in the eastern administrative zones, which had 1.8 million inhabitants, range from 100,000 to 400,000. Kiernan believes that the most likely death toll is 250,000.

For the second half of 1978 there are indications that Pol Pot, contrary to the taciturnity and secrecy shown up to then in public, was about the introduction of a personality cult that was weakened compared to that of Mao or Kim Il-sung . This was due to the social pressure of some of his followers and companions who had benefited from his policies. Large-format photographs of Pol Pot were hung in all communal dining halls until mid-1978, and in documents that had previously always praised the leadership of the party as a whole, it was now Pol Pot whose clairvoyant government was praised. After the fall of the Khmer Rouge, several oil paintings and molds for busts of Pot were found in Tuol Sleng . One goal for these measures could have been to unite the country in the fight against Vietnam with a more personalized leadership, as happened under similar threats in North Korea and China. Even so, Pot, along with Nuon Chea, remained the most hidden Cambodian leader since World War II .

In September 1978, Pot convened a week-long party congress, attended by 60 cadres . He gave a speech on the anniversary of the founding of the KPK, which was later published in the party newspaper Tung Padevat and is thus one of the few speeches that have come down to us. In that speech he presented a new four-year plan that would lead the country to victory against Vietnam. Pot called for the creation of model cooperatives based on the model of the Chinese Dazhai and formulated the goal that by 1980 a third of all cooperatives should be self- sufficient. He also stated that livelihoods for 90% of the population had improved and that several industries had emerged. Of these, however, quite a few had already existed under Sihanouk's rule and had only been rehabilitated with support from North Korea and China. He presented the defeat of Vietnam as inevitable and stated that Hanoi had learned nothing from the history and the defeats of Napoleon, Hitler and American imperialists.

On December 22, 1978, just before the invasion of Vietnamese troops and the subsequent collapse of the regime, Pol Pot met Elizabeth Becker and Richard Dudman from the United States. They were the first journalists from a non-socialist country to visit Democratic Kampuchea. They were accompanied by the British scholar Malcolm Caldwell , who was a supporter of the Khmer Rouge and who had written several writings in defense of their regime. The questions concerning, among other things, the human rights violations, the fate of Sihanouk and the identity of the members of the government had been forwarded in advance. Pol Pot did not discuss them during the conversation, but held a monologue lasting several hours. Only then could Becker and Dudman ask a few questions that were mostly ignored. Becker later said that instead of an interview, she had received a lecture. In terms of content, Pol Pot primarily represented the threat to Cambodia from Vietnamese aggression. Possibly in the hope of meeting sympathy in Washington , similar to the pro-Chinese and Moscow-critical Nicolae Ceaușescu , he claimed that the Warsaw Pact had opposed Cambodia and therefore stirred Pot an intervention by NATO . Her companion, Caldwell, was shot dead in the hotel under unexplained circumstances a few hours after his conversation with Pol Pot about agricultural and socialist economic policy. According to his biographer Chandler, Pot is unlikely to be responsible for this murder.

Fall and ground

On December 25, 1978 Vietnam began with 14 divisions and the support of 15,000 fled from the Reds Khmern Cambodians, including the later Prime Minister Hun Sen , a major offensive in Cambodia . The technically inferior Cambodian troops were quickly outmaneuvered despite courageous resistance. On December 29, 1978, Pot gave a three-hour interview to a Marxist-Leninist delegation from Canada and spoke of the impending defeat of Vietnam, which was supported by the Warsaw Pact. On January 5, after a disturbing statement against Vietnam and Soviet expansionism was published, he met with Sihanouk in the afternoon, who had narrowly escaped an attempted kidnapping by a Vietnamese special command three days earlier. Pot convinced the monarch to leave the country on a Chinese plane the next day and to campaign for the Khmer Rouge regime at the United Nations . Equipped with a very large map, he also showed Sihanouk how the troops of Vietnam would be destroyed in the next two months. The following afternoon, Sihanouk took the last outbound flight before taking Phnom Penh. Just a few hours before the Vietnamese troops entered the capital, around 9:00 a.m. on January 7, 1979, two helicopters transported Pot and his closest confidante into exile in Thailand. The remnants of the Cambodian army, around 30,000 men, fled with around 100,000 rural residents and conscripts to the northwest to the wooded border area with Thailand, killing thousands of malnutrition and fighting. Many party cadres joined this refugee movement, while those who remained in their villages were often killed by the residents.

After the conquest of Phnom Penh on January 7, 1979, Hanoi initiated the proclamation of the People's Republic of Kampuchea with a pro-Vietnamese government led by Heng Samrin , a defector of the Khmer Rouge, and other Cambodians who had fled to Vietnam. This satellite state was isolated internationally at the insistence of China and the United States and, apart from Vietnam, only supported by the Soviet Union and its allies and India. With the help of their allies, such as the ASEAN states, Beijing and Washington succeeded in ensuring that representatives of the Pol Pot regime that had fled Cambodia continued to represent Cambodia at the United Nations, which is a historically unique event. As a result, the poverty-stricken People's Republic of Kampuchea was cut off from development aid by the world community. Thailand, which feared a Vietnamese invasion after the capture of Phnom Penh, agreed with China in January 1979 to accept the Khmer Rouge if, in return, Beijing stopped supporting the guerrillas of the Communist Party of Thailand . Little is known about Pol Pot's whereabouts in 1979. He only reappeared towards the end of the year and was photographed in a fortified camp in eastern Thailand. This camp, which was relocated several times, later became known as Office 87 , which alludes to the earlier code name 870 for the Central Committee of the Cambodian Communists. There he gave several interviews to journalists from Japan, Sweden and the United States in December 1979, which was his last contact with the press until 1997. It was here that he first revealed his true identity as Saloth Sar and accused Vietnam of being responsible for the millions of deaths that had occurred during his reign. Only a conversation with one of his supporters in January 1981 has been handed down and gained notoriety because he dealt with the autogenocide and blamed it on cadres trained in Vietnam who had not informed him about the catastrophic conditions. Shortly after the December 1979 interviews, he announced his resignation as Prime Minister of Democratic Kampuchea and appointed Khieu Samphan as his successor. This move was probably made because Pol Pot had become too much of a burden on the public relations work of the government-in-exile.

By the end of 1979, more than 100,000 Khmer Rouge, around half of them combat troops and support forces, had fled to Thailand, where some of them lived in makeshift refugee camps with Cambodians who had previously fled their regime. By mid-1980 they organized their own, strictly disciplined camps, while 300,000 Cambodian refugees left Thailand and sought asylum in other countries . Pol Pot, who commanded the remnants of his army and about 100,000 other followers, was supported in exile not only by Thailand but also by China and the United States because they shared his hostility towards Vietnam. Since some of these protective powers were powerful nations, he relied on their support for survival and they shared his main goal of driving Vietnam out of Cambodia, Pol Pot overlooked the fact that with this dependency he was violating one of his four basic principles, self-sufficiency.

In 1981, global revulsion for Pol Pot and the rejection of the Vietnamese occupation by many Cambodian refugees led the United States and its allies to urge the United States and its allies to form a non-communist coalition government in exile and to stop sending the Khmer Rouge as representatives to the UN . The Central Committee reacted to this in December 1981 by allegedly dissolving the KPK, although most of the leadership members retained their positions. In the middle of 1982 a government coalition was finally formed, which was dominated by the communists. The other two political groups were headed by Sihanouk, who had founded FUNCINPEC the year before , and Son Sann . Sann was Prime Minister of Cambodia in the late 1960s and launched the anti-communist Khmer People's Liberation Front (KPNLF) in 1979 in the fight against Phnom Penh . Prime Minister Khieu Samphan acted together with Son Sen as spokesman for Democratic Kampuchea abroad. From Thailand, the guerrilla war against the Vietnamese and the People's Republic of Kampuchea continued, especially during the rainy season and the associated restricted mobility of heavy weapons , with the Khmer Rouge forming the most powerful militia. Conquered territory could never be held for long and the troops of the coalition government were always thrown back over the border into Thailand by the Vietnamese People's Army and the armed forces of Cambodia. An exception was the mountain region of Phnom Malai near the border in the Cambodian province of Banteay Meanchey , which could be held longer and to which Pol Pot temporarily relocated its headquarters. The recruiting took place in the refugee camps in Thailand, which were controlled by the government in exile and financed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees .

No speeches or writings from Pol Pot are known from the period 1981 to the end of 1986, only two photographs of him exist. With the exception of a hospital stay in China in 1985, he stayed in sheltered camps on the border between Cambodia and Thailand the whole time, according to Chandler. Political scientist Kelvin Rowley, on the other hand, says Office 87 was in Bo Rai and Pol Pot made repeated trips to Bangkok and Beijing both to seek treatment for his deteriorating health and to hold political talks. Until 1985 he was the chief commander of the militias of the Democratic Kampuchea. In August 1985 it was announced that he would retire from this post and be appointed head of a higher institute for national defense , about whose function nothing is known. Pol Pot resigned from this post in 1989 and served as Communist Party Secretary probably until 1997 . During this time, the guerrilla war of the Khmer Rouge and its allies included the extensive laying of anti-personnel mines , which in the 1990s fell victim to thousands, including many civilians. Khieu Ponnary, who probably had paranoid schizophrenia in 1970 and, according to Nuon Chea, had again suffered from severe symptoms of a mental disorder such as aphonia since 1974 , had not appeared in public since appearing at a party event in 1978 and was considered insane. In the early 1980s, she was treated for long periods in a Beijing hospital, probably due to a severe nervous breakdown. In 1985, Pol Pot received permission from Khieu Ponnary to marry Mea Son, also known as Muon. The following year, Pol Pot's second wife gave birth to their first child, a daughter named Sith.

In 1988 the darkness that Pol Pot was hiding somewhat cleared when the United States Embassy in Bangkok obtained a document from one of the camps of Democratic Kampuchea. It dates to December 1986 and comes from an anonymous author, with the style and ductus speaking strongly in favor of Pol Pot as the authors. Probably designed as a keynote address for a working session of the party cadres, the history of the Democratic Kampuchea is sketched on 39 pages without even mentioning the Communist Party. In addition to the justification for unspecified errors, which would, however, be clearly exceeded by the services, the numerous attacks on representatives of different views are particularly revealing. This includes states that criticized the Pol Pot regime for violating human rights and the non-communist coalition partners in the government, which received increasing support from Cambodians from abroad and from the Thai refugee camps. Deeply distrusting the factions of Sihanouk and Son Sann, Pol Pot calls in this pamphlet to develop as much ideological power again to defeat Vietnam and the non-communist coalition partners. The political slogan “nation, democracy and livelihood” is intended to appeal to all social classes, but was certainly not a departure from the Stone Age communist ideology, but merely a means to the end of a return to power. Pol Pot further explains in the document that, alongside the short-lived Paris Commune, the Democratic Kampuchea was the first state in over 2,000 years in which “ordinary people” like himself exercised government power. He attributes mistakes such as the sometimes "somewhat excessive" behavior to the historical inexperience of ordinary people with administrative matters. Globally, Pol Pot regards the Democratic Kampuchea as the best state in the world and compares it sketchily with the Soviet Union, China, Vietnam, the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Australia , all of which suffered from shortages. In this rhetoric, following Sihanouk's speeches from the 1960s, he emphasizes that Cambodia has never attacked or usurped other nations and in this sense is more innocent than other countries. At the end of the text, Pol Pot speaks out against any personality cult and cites as negative examples Napoleon and four Cambodians who had unsuccessfully fought against French colonial rule in the 19th century. In comparison, he again emphasizes the alleged historical uniqueness and size of Democratic Kampuchea. At no point in this speech does Pol Pot use the first- person form and only casually mention himself, which was typical of his method of covering up his own role and describing terror with glossing over words.

The political change triggered by perestroika and glasnost in the Soviet Union under the leadership of Mikhail Sergejewitsch Gorbachev and the departure from the Brezhnev doctrine meant that Cambodia and Vietnam received less and less military aid from the Warsaw Pact. In addition, Vietnam increasingly oriented itself towards the reform and opening-up policies of Beijing and endeavored to reduce its defense budget . As a result, Hanoi gradually withdrew its occupation forces from Cambodia completely by September 1989. The government in Phnom Penh began with liberalization, among other things, restrictions in the practice of religion were lifted and the real estate market was privatized, which increased its popularity among the population. Probably in response to these measures, Democratic Kampuchea announced the final retirement of Pol Pot. The withdrawal of the Vietnamese armed forces took advantage of the coalition troops around the Khmer Rouge to capture a considerable area of Cambodia and thus create an economic basis for themselves. In 1990 they conquered Pailin and the surrounding gemstone deposits. The sale of sapphires , rubies , wood and land, especially to Thailand, generated substantial revenues that exceeded 100 million US dollars in 1992. In the course of the 1980s, Indonesia, Australia and France in particular exerted increasing pressure on the United States, China and Thailand, the protective powers of the Khmer Rouge, to finally end the blockade of Cambodia. To seek another factor that moved the coalition government to reach an understanding with Phnom Penh, was the increasing popularity of Prime Minister Hun Sen . After Democratic Kampuchea long delayed a political solution to bring more areas under control and Phnom Penh waited on Hanoi's advice, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the collapse of state socialism in Eastern Europe brought about a geopolitical change. The governments of China and Vietnam, who wanted to maintain the communist social order, sought an agreement to end the proxy war over Cambodia. Since 1987 there had been peace conferences in Thailand, France and Indonesia, which had less the character of negotiations between the coalition government and the People's Republic of Kampuchea than of four-party talks, which were led by the Khmer Rouge, the factions of Sihanouk and Son Sann and Phnom Penh were formed. Due to the increasing pressure from Beijing and Hanoi, the Khmer Rouge and Sihanouk soon felt compelled to cease their promising acts of war, while the state of Cambodia , as it called itself since the withdrawal of Vietnam, renounced the further demonization of the Pol Pot regime and part of it transferred national sovereignty to the UN. Pol Pot was probably present in person at crucial negotiations in Pattaya in June 1991 . After the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council pledged their support, the Supreme National Council for Cambodia was formed, in which all four political groups were represented. In October 1991 the Paris Peace Accords were finally signed . According to reports from defectors, Pol Pot was cautiously optimistic and calm during this tumultuous period.