So Phim

So Phim (* around 1925 ; † June 3, 1978 in Prek Pra), born as So Vanna , also known as Sos Sar Yan and Ta Phim , was a Cambodian politician and military leader of the Khmer Rouge .

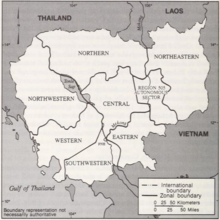

He was a permanent member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Kampuchea , First Vice President of the State Presidium and Secretary (Head of Government) of the Eastern Zone Committee of Democratic Kampuchea . During the 1978 wave of Khmer Rouge cleanups in the Eastern Zone, he was attacked and seriously injured while attempting to contact the leadership in Phnom Penh . In a hopeless situation, he took his own life.

biography

So Phim was born in eastern Cambodia around 1925 . He began his military career in the French army before becoming a functionary of the Khmer Issarak independence movement in the late 1940s . He was also a member of the Vietnam-dominated Indochinese Communist Party, which was dissolved in 1945 .

In August 1951 he was one of the five founding members of the People's Revolutionary Party of Kampuchea (PRPK), which was renamed the Workers Party of Kampuchea (WPK) in 1960 and the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) in 1971.

In 1954, when the Geneva Agreement ended the First Indochina War, he returned to Cambodia after a short stay in Hanoi and became one of the four members of the provisional committee that was to lead the party. Since the PRPK was threatened by Norodom Sihanouk's police and the betrayal of its own leaders, Phim fled with some supporters to Phnom Penh , where they could work as carpenters.

In 1960 Phim was elected a candidate member of the Central Committee of the WPK, three years later a permanent member, placing him fourth or fifth in the party hierarchy. The five-member Central Committee was dominated by anti-Vietnamese intellectuals, headed by Pol Pot . So Phim was the only one of peasant origin.

From 1954 until his death in 1978, he was secretary of the Eastern Zone Committee (Government) of Democratic Kampuchea .

So Phim is described as “a stocky man about six feet tall, with a round face, dark skin and stiff black hair”. He was considered impolite and threatened his comrades with his pistol in a fit of anger. Nonetheless, he appears to have been loved by his men and had a potentially unjustified reputation in the party for being moderate. Phim had a persistent skin condition and was treated in China from May to August 1976.

In his zone, especially in Kampong Cham Province , the Muslim Cham who refused to obey the rules established by the Khmer Rouge were brutally suppressed.

Internal party tensions

In the Khmer Rouge, there was an animosity between intellectual (urban) and rural (rural) cadres, the former more anti-Vietnamese, the latter more provietnamese. While North Vietnam was still their closest ally in the struggle of the Khmer Rouge against the pro-Western regime of the Khmer Republic of Lon Nol , the historical anti-Vietnamese rivalry of the urban line began to gain the upper hand after they came to power. The gap with rural, Pro-Vietnamese cadres like So Phim and Heng Samrin widened . Pol Pot turned away from Vietnam and the Soviet Union and increasingly towards China. His hatred of Vietnam was based on the conviction that the territory in Kampuchea Krom ( Mekong Delta ) and the Vinh-Te Canal had been illegally ceded to Vietnam by "monarchist and feudal authorities" and the French colonizers and had been " brought home " would have to be. An insult in Saigon, which originated in their youth, when the Khmer there were called "dark monkeys from the mountains" because of their darker skin, may also have played a role. The regime also had territorial claims vis-à-vis the other two neighbors, Laos and Thailand ( Surin , Buri Ram and Si Sa Ket ), and in general to all areas where stones with the inscription “Khom” could be found or where sugar palms grew.

The troops of the individual seven zones established by the Khmer Rouge were relatively autonomous, and in some cases even equipped with different uniforms. In July 1975 the headquarters tried to reorganize the troops under their control, with moderate success. The zones were then de facto occupied by the troops of the central and the south-western zone, which was devoted to it and led by a strict anti-Vietnamese Khmer Rouge with Ta Mok . Most of the resistance to the headquarters was in the Eastern Zone. Shortly after the Khmer Rouge came to power in September 1975, there was an unsuccessful attempt at a coup in which So Phim was possibly involved.

In early 1977 the center introduced a new command structure in the Eastern Zone. The southern twin regions of the zone were now led by the deputy secretary Seng Hong (alias Chan), a sworn irredentist who even wanted to "bring home" Prey Nokor ( Ho Chi Minh City ) after the occupation by troops of the southwest zone . The center introduced two new fronts, the Highway 1 front with Son Sen , Minister of Defense and Commander in Chief of the National Army, as commander, and the Highway 7 front. The command for this was handed over to So Phim, but with Ke Pauk , the secretary of the Central Zone, a loyal Red Khmer was assigned to him as a deputy. The eastern zone, like the others, except the south-western zone, was now essentially occupied by foreign troops. The pressure on So Phim increased.

Attacks against Vietnam

The attacks on Vietnam began in the spring of 1977, after border incidents with Thailand and Laos at the beginning of the year. They were justified by the regime with alleged annexation plans of Vietnam. The Khmer Rouge now described Vietnam as the aggressor and enemy of the Democratic Kampuchea .

On March 15-18 and March 25-28, 1977 troops of the Democratic Kampuchea raided the Vietnamese provinces of Kiên Giang and An Giang . Strong Cambodian forces raided Vietnamese border guards and villages between April 30 and May 19, killing 222 civilians and bombarding the provincial capital on May 17. Shortly before mid-1977, troops from Democratic Kampuchea attacked Vietnamese villages along the border and killed 200 civilians, including ethnic Khmer, in the village of Prey Tameang.

For the time being, Vietnam was reluctant to strike back militarily. Hanoi could not imagine waging a war with its former close ally, who was still called "Brother", and repeatedly made unsuccessful proposals to end the conflict peacefully.

In March 1977, the special regiment of Region 21 under the command of Hun Sens received the order to attack the Vietnamese village of Or Lu in the Loc Ninh province. The order apparently came from Seng Hong and Kev Samnang, the military commanders of the Eastern Zone. The political commissar of the special regiment, Sok Sat, and his deputy Chum Sei defied the order. When Hun Sen found out that 20 of his comrades had also been killed, he decided not to carry out the attack.

Eastern Zone Purges 1977

Then the large-scale purge in the Eastern Zone began with extreme brutality. In April 1977 the 75th battalion of the regiment was the first to be disarmed. Within two weeks, CPK security forces arrested 100 officers and soldiers from Eastern Zone forces. Then the 35th, 55th and 59th Battalions were also disarmed. By June, 200 region 21 military cadres had been killed, including Political Commissars Sok Sat and Chum Sei, according to Hun Sen.

The purge also spread to regional 21 political cadres. Many were taken to the S-21 ( Tuol Sleng ) central prison in Phnom Penh, where they were tortured to extract confessions of other "traitors" from them. Hundreds of cadres were killed and thousands arrested. Many fled to Vietnam. By October 1977 there were 60,000 Cambodian refugees in Vietnam. In early July 1977, six military commanders from the Eastern Zone fled to Vietnam near Memut, a little further south to Sin Song and two other defectors, including the then 25-year-old Hun Sen.

Tây Ninh massacre

On the night of September 24, 1977, units of the 3rd Division of the Eastern Zone, under the command of Son Sen, invaded Tây Ninh province and massacred nearly 300 civilians in five villages in Tan Bien and Ben Cau districts. Many of the victims were ethnic Khmer or Vietnamese who had fled Cambodia. The Vietnamese retook the districts in a week. At the same time, Pol Pot made a triumphant visit to China and made his declaration in a radio speech lasting several hours that Angka was the CPK and he was the leader of the party. On October 5, 1977, the Chinese Ministry of Defense signed an agreement for a comprehensive arms shipment to Democratic Kampuchea .

The Tây Ninh massacre put an end to Vietnam's reluctance and hope of an understanding with its former ally. The first retaliatory measures followed in October 1977. Vietnam was now preparing for a large-scale retaliation operation, initially with reconnaissance missions. On December 22, 1977, two tanks entered the city of Kandol Chrum, intending to contact Son Phim, but had to return without having achieved anything. Hun Sen, Heng Samrin and eight other Cambodian defectors accompanied the Vietnamese on their reconnaissance missions.

Despite his Pro-Vietnamese stance, loyalty to the party and to Pol Pot prevailed with So Phim, and he did not protest the attacks, even giving orders to attack himself. But after Tây Ninh was retaken by the Vietnamese, Phim and Heng Samrin were accused by the center of collaborating with Vietnam, which eventually led to the coup against Phim in May 1978.

Retaliation by Vietnam

On December 31, 1977, Vietnamese tanks and infantry invaded Cambodia again. The troops of the Eastern and Central Zone immediately withdrew to the west in disorder. On the same day, the Democratic Kampuchea broke off diplomatic relations with Vietnam. Shortly thereafter, Pol Pot called for war against Vietnam and ordered the deployment of up to 60% of the Cambodian troops.

On January 6, 1978, the Vietnamese troops returned to Vietnam. Over 100,000 Cambodians took the opportunity to flee with them. One of them was Heng Samrin's brother, Heng Samkai, Chairman of the Eastern Zone Couriers. He reached the border in January 1978 and was taken by helicopter to Ho Chi Minh City, where he reunited with other Cambodian defectors.

Coup and uprising in the Eastern Zone in May 1978

Shortly thereafter, Pol Pot organized a public meeting at Wat Taung in Suong District of the Eastern Zone. Son Sen, So Phim, Ke Pauk and Heng Samrin were also present. While Pol Pot called for a war against the "hereditary enemy" Vietnam, Radio Phnom Penh spoke of a "traitor clique" in the zone that supported Hanoi. Pol Pot now harbored a general suspicion against all cadres of the Eastern Zone that they had allied themselves with Vietnam, and equated the Eastern Zone and its 1.5 million inhabitants with Vietnam and the Vietnamese enemies. They are "Khmer in shape, but Vietnamese in their heads".

On February 5, 1978, Hanoi proposed an agreement to end the border conflict, which included negotiations and a withdrawal of troops from both sides 5 km from the border with international surveillance. The Democratic Kampuchea regime even refused to accept the proposal and rather prepared for an intensification of the war by relocating the population from particularly vulnerable areas. Hanoi, for its part, decided at the end of February to take military action against the Democratic Kampuchea regime and overthrow it. The decision finally made the Eastern Zone the center of the intra-Cambodian uprising against the Khmer Rouge regime.

On March 14, 1978, troops from the Democratic Kampuchea invaded the Vietnamese province of Ha Tien and killed up to a hundred residents, including people of Khmer origin. By June 1978 around 750,000 Vietnamese had fled the border area into the interior of the country.

In late March 1978, Pol Pot sent Deputy Prime Minister and Economy Minister Vorn Vet to the Eastern Zone to take So Phim, who was ill, to a hospital in Phnom Penh. Phim suspected that action should be taken against him, but after some hesitation went with him. After the hospital stay, he went to his home with Ros Nhim, Secretary of the Northwest Zone. After returning to Tuol Preap in the Eastern Zone in April, although not completely recovered, he found that she had been devastated by headquarters. By April 19, 1978, there were 409 Eastern Zone cadres in Tuol Sleng, far more than any other zone.

In May 1978, Ke Pauk called the commanders and political commissars of the three Eastern Zone divisions to meet at his headquarters in Sra. Upon arrival, they were disarmed and arrested, and many were executed on the spot. 92 of the most important cadres were handed over to headquarters for trial. Heng Samrin escaped the purge because Phim sent him to Prey Veng , the zone's military headquarters . From there he could command various battalions.

Pauk now also ordered Phim to a meeting. The latter, still ill and not aware of the full extent of the cleanup, was surprised that the deputy ordered his superiors to meet. Instead, he sent one of his bodyguards, Mey, to see Pauk. He was immediately arrested and executed. Pauk ordered Phim to the meeting again, who sent another bodyguard who was dealt with immediately. After a third order, Phim sent his nephew Chhoreun to Pauk to inquire about the whereabouts of the bodyguards. This was also killed. Finally, Phim sent his office manager Piem to Pauk to represent him there. Pauk arrested him and sent him to Tuol Sleng. It was only after Piem did not return that Phim realized that Pauk was putting on a coup against him. On May 24, 1978, Phim met with the deputy chief of staff, Pol Saroeun, who ran the ammunition factory in Koh Sautin district. Phim ordered him to summon loyal troop leaders, but at the same time warned him not to cooperate with Vietnam. However, he did not order him to attack Pauk's forces. The next day Pauk struck. Two divisions of the Central Zone crossed the Mekong , where they encountered spontaneous resistance from eastern troops on the scale of a regiment. A struggle of unequal forces ensued for three days and nights.

Phim asked Heng Samrin to relieve him from Tuol Preap, and the latter brought him back to Prey Veng. He invited the remaining commanders to a meeting. Around 20 commanders and political leaders gathered. In contrast to Samrin, Phim was still undecided and did not believe that Pol Pot was behind the coup, but Son Sen, who wanted to replace Pol Pot as leader. However, he agreed to attack Pauk, but that would require the support of Vietnamese friends. Most of the other commanders wanted to strike back immediately. Phim finally pushed through a personally courageous, but politically weak compromise: He went to Phnom Penh to investigate the situation. If he hasn't returned within three days, they should fight back. He went to Phnom Penh with only six bodyguards.

Samrin, however, immediately organized the military resistance. Fierce fighting broke out with Son Sens and Pauks' troops. The first successes of Samrin's troops encouraged the residents of the Eastern Zone to launch local rebellions. A crowd gathered in Babong, demanded food and beheaded two Khmer Rouge from the city council. In Chamcar Kuoy, farmers beheaded the head of the town and four others.

Attempt to reach an agreement with Pol Pot and Tod

In the meantime So Phim had reached Arei Khsat, on the opposite side of the Mekong from Phnom Penh. He sent one of his bodyguards to the military commander's office with a message of unknown content. The message was passed on to Pol Pot, and the bodyguard returned empty-handed. Phim decided to wait for an answer. An hour later, two ferries full of marines approached the center. Phim still assumed they would escort him to the capital. But the marines got off the ferries, opened fire and seriously injured Phim in the stomach. He managed to get to Arei Khsat's office and escaped to a wat near Prek Pra in the horse-drawn carriage of the head of the sub-district.

After three days, Samrin, together with the Secretary of Region 21, Chhien, and the head of the Economic Department of the Eastern Zone and uncle of Pol Saroeun, Sarun, went in search of Phim and found him at the Wat. Phim greeted them with "Farewell". He was finished, could no longer, but they should keep fighting. He was bleeding from his stomach and drank alcohol to ease the pain. His wife Kirou and three children came to see him at the wat. Samrin asked him to come, but Phim insisted on staying. Samrin organized the troops of the Srei Santhor district, 300 soldiers in three companies, and Yi Yaun, the district's secretary, with the task of bringing Phim to the jungles of Srei Santhor.

Samrin left the wat on May 31, 1978 at 4:00 p.m. He commissioned the commanders of Prey Veng and others to prepare a plan to relieve Phim and his transfer to Vietnam. But the next day they were attacked by enemy troops and suffered great losses. The troops eventually occupied Prey Veng. Planes were now dropping leaflets over the Eastern Zone stating that Phim was a traitor and should be captured, dead or alive. Some of them also reached the men of the Srei Santhor district, whom Hamrin had entrusted with protecting Phim. In the absence of district chief Yi Yaun, they handed a leaflet to his deputy. He, in the opinion that the party or its air force could not be wrong, ordered Phim's arrest. On June 3, 1978, a force of 300 men circled the wat and Phim lost all hope. Shortly after sunset, he picked up his pistol and shot himself first in the chest, then in the mouth. His death ended a thirty-year revolutionary career that began with resistance to the French colonial regime in the 1940s. Phim's loyal bodyguards fled to a nearby village and dispersed. When Phim's wife, Kirou, and the three children were about to prepare his body for the funeral at 9:00 p.m., they were massacred.

Phim was replaced at the head of the Eastern Zone by Nuon Chea , brother No. 2 and deputy Pol Pot, a close friend and long-time companion of Phim, who nevertheless could not or would not prevent his demise. He was told by prisoners from Tuol Sleng that Phim had sold rice to Vietnam without asking permission from the center.

aftermath

However, the center's triumph over the popular Phim did not achieve its goal. After his death, residents of Region 22 and Komchay Meas rebelled with great anger. They had long wanted to reverse collectivization and make private agriculture possible again. They distributed ox carts and other agricultural implements among themselves. The rebellion took on ever greater proportions and expanded into the province of Kratie , the special region 505 between the Central and Northeastern Zone. By mid-1978, about 2,000 men were under rebel command. Pauk's deputy Sok also fled to Vietnam and came back as a rebel fighter.

The regime struck back. In the first semester of 1978, 5,675 prisoners were brought to Tuol Sleng, compared with 6,330 in 1977. Spontaneous executions of surrendering rebels and villagers suspected of collaborating with them drove tens of thousands into the jungle. The Central Forces completely wiped out the 700 residents of So Phim's home base in Bos in the Ponhea Krek district. In region 22, troops from the southwest zone carried out one of the worst massacres in July / August 1978 in a hospital in the Peareang district. On September 4, 1978, 27 men, three women and two children in Don Sor sub-district were beaten to death with bamboo canes and axes. A week later, security forces in the Southwest Zone seized an additional 930 people from families whose members had been executed. Between September 16 and 20, 1978, all 930 were massacred.

The Khmer Rouge began evacuating residents of the Eastern Zone in mid-1978, mostly to the Northern and Northwestern Zones. They were forced to wear a blue scarf that identified them as being from the Eastern Zone and made them easy victims. Kiernan estimates the number of people massacred in the Eastern Zone in 1978 based on numerous interviews at 100,000 to 250,000 people. Other estimates, including an extrapolation from Katuiti Honda's data, put up to 400,000 victims. The invasion of Vietnam in December 1978 with the help of the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation and the proclamation of the People's Republic of Kampuchea then overthrew the government of the Khmer Rouge and put an end to the horror.

literature

- Ben Kiernan : Brother Number One. A Political Biography of Pol Pot. Revised Edition. Silkworm, Chiang Mai 2008, ISBN 978-974-7551-18-1 .

- Ben Kiernan: Genocide and Resistance in Southeast Asia. Documentation, Denial, and Justice in Cambodia and East Timor. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick / London 2008, ISBN 978-1-4128-0668-8 .

- Gina Chon, Sambath Thet: Behind the Killing Fields. A Khmer Rouge Leader and One of His Victims. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia / Oxford 2010, ISBN 978-0-8122-4245-4 .

- Solomon Kane: Dictionnaire des Khmers rouges. So (Phim) (Translator: François Gerles, preface by David Chandler). Institut de Recherche sur l'Asie du Sud-Est Contemporaine (IRASEC), Bangkok 2007, ISBN 978-2-916063-27-0 .

- Philip Short: Pol Pot. Anatomie d'un cauchemar (Translator: Odile Demange; Original: Pol Pot.Anatomy of a Nightmare ). Denoël, Paris 2007, ISBN 978-2-207-25769-2 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kane: Dictionnaire des Khmers rouges. So (Phim). 2007, p. 349.

- ^ Kiernan : Genocide and Resistance in Southeast Asia. 2008, p. 86 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Henri Locard: Pourquoi les Khmers rouges. L'Angkar (= Révolutions ). Vendémiaire, Paris 2013, ISBN 978-2-36358-052-8 , p. 110.

- ↑ Kane: Dictionnaire des Khmers rouges. So (Phim). 2007, p. 350.

- ↑ Short: Pol Pot. 2007, p. 157.

- ^ Nayan Chanda: Les frères ennemis. La péninsule indochinoise après Saigon Translated by Michèle Vacherand, Jean-Michel Aubriet. CNRS Éditions, Center national de la recherche scientifique, Paris 2000, ISBN 978-2-87682-002-9 , chap. 8: Le feu aux poudres , p. 216 (Original title: Brother Enemy. The War After the War ).

- ↑ David P. Chandler : So Phim. In: Encyclopedia of Mass Violence. November 14, 2008, archived from the original on April 24, 2016 ; accessed on August 6, 2019 .

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 89 f.

- ↑ Short: Pol Pot. 2007, p. 231.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, pp. 296-373.

- ^ Kiernan: Genocide and Resistance in Southeast Asia. 2008, p. 92 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Kiernan: The Pol Pot Regime. 2008, pp. 262-277.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 360.

- ↑ a b Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 387.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 368.

- ^ Russell R. Ross: An Elusive Party. In: Cambodia - A Country Study. Library of Congress Country Studies , Washington, 1987, accessed August 6, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 392.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 369.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 357.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 358.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 373.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 374.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 375.

- ^ Kiernan: Genocide and Resistance in Southeast Asia. 2008, p. 92 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Kiernan: Genocide and Resistance in Southeast Asia 2008, p. 94 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 380.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 386.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 393.

- ↑ a b Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 389.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 388 f.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 394.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 395.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 396.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 397.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 398.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 399.

- ↑ Chon, Thet: Behind the Killing Fields. 2010, p. 113 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Chon, Thet: Behind the Killing Fields. 2010, p. 115 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 400.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 402.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 403.

- ↑ a b Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 404.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 409.

- ↑ Katuiti Honda: Journey to Cambodia. Investigation into Massacre by Pol Pot Regime. Committee of Journey to Cambodia, Tokyo 1981.

- ↑ Kiernan: Brother Number One. 2008, p. 405.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | So Phim |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | So Vanna; Sos Sar Yan; Ta Phim |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Cambodian politician and military leader |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1925 |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 3, 1978 |

| Place of death | Prek Pra |