Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum

The Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum is the former S-21 prison of the Khmer Rouge and serves to commemorate the crimes committed there during the genocide in Cambodia between 1975 and 1979 at the time of the Democratic Kampuchea . It is located in Phnom Penh , the capital of Cambodia .

S-21 was one of 196 prisons in Democratic Kampuchea . It was directed by Kaing Guek Eav , aka Duch. About 18,000 people were held here.

Although it is often described as a torture center, it was more of a detention center because not all detainees were tortured. However, death was inevitable for every prisoner. A person admitted to S-21 was systematically considered guilty, and if necessary, a confession was forced.

Tuol Sleng can be called " Brechnuss be translated hill". That was the name of the elementary school that was next to the grammar school where the museum is located today. This was part of the prison and was called Tuol Svay Prey (wild mango tree hill). The size of the prison extended far beyond the present museum grounds and extends over the entire quarter. Among other things, a hospital, fields, banana plantations, houses converted into torture chambers and accommodation for the staff could be found there.

A former school used as a prison

The ensemble of buildings is a former Phnom Penh high school built in the 1960s , which was called Tuol Svay Prey during the Khmer Republic of Lon Nols (1970–1975) and Ponhea Yat during the time of Sihanouk (1941–1970) . Located on 103rd Street, it was used as a prison by the Khmer Rouge after the conquest of Phnom Penh. For this purpose, the four buildings of the school were fenced in with an electric fence and the classrooms were converted into prison cells and torture chambers. Barbed wire mesh in front of the outer corridors of the individual building sections was intended to prevent desperate prisoners from committing suicide.

Although S-21 had existed as an institution since August 1975, it was only in April 1976 on the orders of the former school teacher Duch billeted in the place where the museum is today. The prison existed until January 7, 1979, when the Vietnamese invaded Phnom Penh and liberated the city.

The prisoners

The information on the total number of people imprisoned in S-21 varies. According to the original extrapolation of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), which is based on the incomplete archive of the museum, the total number of inmates was "at least 12,273". The Cambodia Documentation Center (DC-Cam) assumes in its publications that 20,000 people were imprisoned in S-21. According to the latest ECCC extrapolation now being used by the researchers, 18,000 people were detained in S-21.

The first inmates of S-21 were soldiers and officials of the Lon Nol regime , who arrested the Khmer Rouge immediately after they came to power in April 1975. From 1976 people from the ranks of the Khmer Rouge were also sent to S-21 as a result of waves of political cleansing (from the armed forces, the ministries, etc.). These were mainly soldiers from the northern and eastern administrative zones and a network of intellectual leadership cadres of the Communist Party of Kampuchea around So Phim , Hu Nim and Koy Thuon . From the establishment to the liberation of the prison by the Vietnamese armed forces, the victims were also civilians, students, intellectuals, returned Cambodians in exile, Buddhist monks and some foreigners (especially Vietnamese). Sometimes family members were also interned in Tuol Sleng and murdered there.

organization

About 1,720 people worked for the torture center at some point. Among them were around 300 guards and interrogators, the others served as workers or worked in the fields of the S-21.

New prisoners were usually delivered to the S-21 in groups. Sometimes spouses and all children were also brought in so as not to leave behind someone who could later seek revenge. The prisoners were initially housed in a large room on arrival. Many prisoners were chained together in rows on iron bars in order to take them away one by one, take photos and force them to reveal all information about themselves. They then had to undress and all of their belongings were confiscated. Then they were taken to their cells.

Some “better off”, that is, important members of society, were held captive in solitary cells and chained to a cot - mostly in houses next to the former grammar school. Other inmates were placed in solitary cells about two square meters and chained to the wall. These individual cells were created by further subdividing the former school classrooms. An American ammunition box the size of a shoe box was available to the prisoners as a toilet, the traces of which can still be seen on the floor.

Every prisoner had to follow strict rules; laughing, crying, speaking and other communication were forbidden. Violators were punished with flogging or electric shocks, whereby the victims were not allowed to scream. Any action required the permission of the guards. The poor hygienic conditions led to lice infestation and disease.

Torture methods

The torture methods in the S-21 included electric shocks, immersion in water tubs, waterboarding , hanging on a gallows until unconscious, with the hands tied behind the back with a rope and the victim being hung from it, thumbscrews and the introduction of Acid or alcohol used in the nose. Although many people died from it, deliberately killing them in the process was frowned upon, as the Khmer Rouge wanted to obtain confessions first.

In the first few months, the inmates were killed on the premises of the S-21. In 1976/77, however, Duch decided to move the place of execution to Choeung Ek , also to reduce the risk of epidemics. The prisoners were henceforth beaten to death with shovels in the killing fields of Choeung Ek outside the city gates or their throats cut to save ammunition and to avoid the noise of gunfire.

In addition to the torture, there were occasional medical experiments on inmates in order to improve the anatomical knowledge of the medical staff. In addition, blood was drawn from inmates to provide transfusions for wounded Khmer Rouge fighters. In about 100 victims, this treatment resulted in death due to blood loss.

When the prison was about to be liberated, fourteen adult inmates were still alive, but all of them were murdered before the arrival of the liberators. Only four children could be saved. T. had hidden under mountains of laundry. In total, only seven adults survived. Known by name and still alive are the mechanics Bou Meng and Chum Mey as well as the farmer and former Khmer Rouge Nhem Sal ; the artist and survivor Vann Nath died on September 5, 2011. Some of the survivors were painters or sculptors who were supposed to make portraits or cement busts of Pol Pot , “Brother No. 1”.

The former head of the torture center, Kaing Guek Eav , known under the pseudonym Duch , was interrogated in the so -called Khmer Rouge Tribunal from 2007 and confessed to numerous crimes. Duch was found guilty of killing approximately 18,000 people. On July 26, 2010, he was sentenced to 35 years' imprisonment, which was immediately reduced from five years to 30 years for being illegally detained. He had already served eleven years at the time of the judgment. In February 2012, the sentence was increased to life in a review process . He died in custody in 2020.

Tuol Sleng as a museum

The prison was liberated by Vietnamese soldiers on January 7, 1979 after Vietnamese forces invaded Phnom Penh. Duch himself was able to escape after ordering the liquidation of all inmates. However, he no longer had enough time to have the comprehensive documentation of the atrocities committed there destroyed. The Vietnamese left the country in 1989; Duch turned to Christianity and worked for the American Refugee Committee (ARC) under the code name Hang Pin from 1997 until he was arrested in 1999.

From March 1979 international and Cambodian delegations were able to visit the site of the S-21. According to an official document from the Ministry of Culture, the museum did not officially open until July 13, 1980. However, today's museum administration prefers the symbolic date of August 19, 1979 to this date, because on that day Pol Pot and Ieng Sary from a revolutionary people's tribunal established by Vietnam were sentenced to death in absentia.

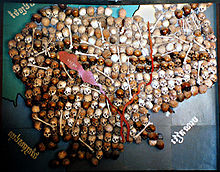

Paintings by one of the few survivors, the painter Vann Nath , can be seen in the museum as well as partitions with thousands of photos of the victims made by the prison staff. The picture of a map of Cambodia made up of skulls at the end of the tour illustrates this deadly phase in the history of the country. However, the card was dismantled on March 10, 2002 as a result of violent protests.

In the 1990s, the museum buildings fell into disrepair due to a lack of financial means.

At the end of July 2009, the archive of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum - consisting of 4186 written confessions, 6226 biographies and 6147 photographs - was registered by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site .

A politically motivated foundation

A Vietnamese consultant, Mai Lam, helped the Cambodian employees set up the first exhibitions. Mai Lam was responsible for setting up the US War Crimes Museum in Ho Chi Minh City and had visited various memorials in Europe.

According to historian David Chandler , the aim of the museum was to create "clear evidence" of the crimes of the Khmer Rouge. On the one hand, this was intended to justify the invasion of Cambodia by the Socialist Republic of Vietnam ; on the other hand, legitimation for the new regime set up by Vietnam, the People's Republic of Kampuchea , was needed . The measure has proven to be successful in part, as Australia and Great Britain diplomatically recognized the People's Republic of Kampuchea in 1980 - while the USA, China and the UN still regarded the Democratic Kampuchea of the Khmer Rouge as the only legitimate representative of the Cambodian people until the 1990s .

The Nazi Analogy and Political Controversy

The museum is often accused of equating the crimes of the Khmer Rouge and, above all, the crimes committed in S-21 with the Nazi crimes , which leads to the fact that the visitors draw incorrect connections between the Democratic Kampuchea and National Socialism . According to historian Rachel Hughes, the museum's first exhibitions encouraged visitors to view "Tuol Sleng as Cambodian Auschwitz " and "Pol Pot as Asian Hitler ". Responsibility for the crimes is transferred to the so-called "Pol Pot-Ieng Sary-Clique" alone, a small group of men whose socialist influences are denied.

According to Judy Ledgerwood, the story in the museum tells of “a glorious revolution stolen and perverted by a handful of sadistic, genocidal traitors who deliberately destroyed three million of their countrymen. The true heirs of the revolutionary movement overthrew this murderous tyranny three years, eight months and twenty days later, just in time to save the Cambodian people from genocide. ”According to this interpretation, the museum was founded only around the 1979 of Vietnam used people's Republic of Kampuchea to legitimize community and hence the present government of Hun Sen . This widespread opinion leads some opposition politicians , such as B. Kem Sohka, deny that there was S-21 and that the crimes described in the museum were committed. They claim that Tuol Sleng was a production that served to justify the invasion of Cambodia by Vietnam and to legitimize the new regime.

literature

- David P. Chandler : Voices from S-21. Terror and History in Pol Pot's Secret Prison . University of California Press, Berkeley CA 1999, ISBN 0-520-22005-6 .

- Vann Nath: A Cambodian Prison Diary. One Year in the Khmer Rouge's S-21 . White Lotus, Bangkok 1998, ISBN 974-8434-48-6 .

- Nic Dunlop: The Lost Executioner - A Story of the Khmer Rouge . Bloomsbury, London 2005, ISBN 0-7475-6671-2 .

- Alexander Goeb: Cambodia - traveling in a traumatized country . Brandes & Apsel, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-86099-724-6 .

- Andreas Margara : The Khmer Rouge Tribunal and the coming to terms with the genocide in Cambodia , Heidelberg 2009, Thuringian Cambodian Society ( text link ; PDF).

Film and art

- Roland Joffé: The Killing Fields - Screaming Land ; 1984.

- Rithy Panh : S-21: The Khmer Rouge's death machine ; 2003.

- Nate Thayer: Death Spirals Saloth Sar alias Pol Pot ; Documentation 2000.

- Herbert Müller (* 1953), German painter, made a cycle of pictures on the Tuol Sleng prison .

- Alexander Goeb, Vann Nath, Heng Sinith: "The Cambodia Disaster" (www.kambodscha-desaster.de)

Web links

- Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum official website

- Yale University Cambodia Genocide Program

- Documentation Center of Cambodia

- Hans Christoph Buch: Sorry, very sorry ; in: Die Zeit, 1999

- Armin Wertz : Curse of the Dead Years , www.freitag.de

- photos

Individual evidence

- ^ Judgment Case 01, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, 07/18/2007, p. 41. [1]

- ^ A b Anne-Laure Porée, "Tuol Sleng, l'histoire inachevée d'un musée de mémoire", Moussons , No. 30, 2017-2, pp. 151-182 (p. 165). [2]

- ↑ Berthold Seewald: It was so well planned in the Pol Pot torture centers. In: The world. September 4, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c d Rachel Hughes, "Nationalism and Memory at the Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide Crimes, Phnom Penh, Cambodia", in Memory, History, Nation: Contested Pasts , hrgb. K. Hodgkin, S. Radstone (Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2005), pp. 175-192 (p. 176).

- ^ Anne-Laure Porée, "Tuol Sleng, l'histoire inachevée d'un musée de mémoire", Moussons , No. 30, 2017-2, pp. 151-182 (p. 156). [3]

- ^ Anne-Laure Porée, "Tuol Sleng, l'histoire inachevée d'un musée de mémoire", Moussons , No. 30, 2017-2, pp. 151-182 (pp. 168-172). [4]

- ^ Anne-Laure Porée, "Tuol Sleng, l'histoire inachevée d'un musée de mémoire", Moussons , No. 30, 2017-2, pp. 151-182 (p. 157). [5]

- ^ Judgment Case 01, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, 07/18/2007, p. 49. [6]

- ↑ a b c Judgment Case 01, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, 07/18/2007, p. 133. [7]

- ↑ Wynne Cougill: Buddhist Cremation Traditions for the Dead and the Need to Preserve Forensic Evidence in Cambodia. Retrieved July 9, 2018 .

- ^ Judgment Case 01, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, 07/18/2007, p. 116. [8]

- ↑ Berthold Seewald: Paranoia drove the Khmer Rouge into their bloodlust. In: The world. May 15, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2017 .

- ^ Judgment Case 01, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, 07/18/2007, p. 134. [9]

- ↑ Preliminary Data Collection of Graffiti Research Project, Chhay Visoth, Bannan Sokunmony, Vong Sameng et Muth Vuth, Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, 2018.

- ↑ Ben Kiernan : The Pol Pot Regime. Race, Power and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79 . (2nd edition). Yale University Press, New Haven (CT) 2002. Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai (Thailand) 2005, ISBN 974-9575-71-7 , pp. 355, 356.

- ↑ a b c History of the Museum. In: Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum Official Website. Retrieved July 9, 2018 .

- ^ Judgment Case 01, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, 07/18/2007, pp. 67-68. [10]

- ^ Bernard Bruneteau: Un siècle de génocides: des Hereros au Darfour, 1904-2004 . Armand Colin, Malakoff 2016, ISBN 978-2-200-61310-5 .

- ^ Judgment Case 01, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, 07/18/2007, p. 96. [11]

- ↑ The Cambodia Daily of June 17, 2009, pp. 1 and 29 (English)

- ↑ Stern: Khmer Rouge chief of torture wants to appeal against prison sentence ( Memento of October 24, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Life sentence for the chief of torture of the Khmer Rouge , Zeit Online, February 3, 2012

- ^ A b c d e Judy Ledgerwood: The Cambodian Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocidal Crimes: National Narrative. In: Museum Anthropology. 21, 1997, p. 82, doi: 10.1525 / mua.1997.21.1.82 .

- ^ A b Anne-Laure Porée, "Tuol Sleng, l'histoire inachevée d'un musée de mémoire", Moussons , No. 30, 2017-2, pp. 151-182 (p. 155). [12]

- ^ Anne-Laure Porée, "Tuol Sleng, l'histoire inachevée d'un musée de mémoire", Moussons , No. 30, 2017-2, pp. 151-182 (pp. 157-161). [13]

- ^ Documents at the Toul Sleng Museum Archives (PDF; 13 kB).

- ^ Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum Archives. In: Memory of the World - Register. UNESCO , 2009, accessed July 5, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c d Chandler, David P .: Voices from S-21: terror and history in Pol Pot's secret prison . Thailand and Indochina ed edition. Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai, Thailand 2000, ISBN 974-7551-15-2 ( nytimes.com [accessed July 10, 2018]).

- ^ Anne-Laure Porée, "Tuol Sleng, l'histoire inachevée d'un musée de mémoire", Moussons , No. 30, 2017-2, pp. 151-182 (p. 166). [14]

- ^ Rachel Hughes, "Nationalism and Memory at the Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide Crimes, Phnom Penh, Cambodia", in Memory, History, Nation: Contested Pasts , hrgb. K. Hodgkin, S. Radstone (Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2005), pp. 175-192 (p. 179).

- ^ Rachel Hughes: Nationalism and Memory at the Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide Crimes, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. In: K. Hodgkin, S. Radstone (Eds.): Memory, History, Nation: Contested Pasts. Transaction Publishers, Piscataway, 2005, pp. 175–192, here p. 181.

-

↑ SED morality . In: The time . No. 6 , 1979 ( online [accessed July 10, 2018]). Tiziano Terzani: "I can still hear screams in the night" . In: Der Spiegel . No.

17 , 1980, pp. 156-167 (on- line ). - ↑ Andrew Buncombe: Cambodia passes law making denial of Khmer Rouge genocide illegal. In: The Independent. June 7, 2013, accessed July 10, 2012 .

- ^ A b Anne-Laure Porée: Tuol Sleng, l'histoire inachevée d'un musée de mémoire. In: Moussons. No. 30, 2017/2, pp. 151–182, here p. 152 , accessed on September 2, 2020 (French).

- ↑ Gerd Stauch (Ed.): What is man that you think of him? Psalm 8, 5 - Works by Herbert Müller: Engerhafe concentration camp and Tuol Sleng prison in Phnom Penh. Aurich 2008.

Coordinates: 11 ° 32 ′ 58 ″ N , 104 ° 55 ′ 4 ″ E