Engerhafe concentration camp

The concentration camp Engerhafe was in the west of Aurich located Engerhafe , now a district of the municipality Südbrookmerland . It was the only concentration camp in East Frisia at the time of National Socialism . It was built on October 21, 1944 as a satellite camp of the Neuengamme concentration camp in connection with the construction of the so-called Friesenwall . The Friesenwall was a planned but only partially completed defense system that was to be built on the German North Sea coast towards the end of World War II . The Engerhafe, Meppen-Dalum and Versen, Husum-Schwesing, Ladelund camps and various work details in Hamburg were involved in the construction. The Engerhafe camp was responsible for the construction of anti-tank trenches around the city of Aurich. Shortly before the completion of the all-round defense of Aurich , the camp was closed on December 22nd, 1944. 188 inmates died within the two months that it existed.

Geographical location

The area on which the labor camp was first built in 1942 and later the Engerhafe satellite camp is located on both sides of today's Dodentwenter Weg, between Achterumsweg and the church in Engerhafe in East Frisia . About three kilometers from the actual camp is Georgsheil , where the railway lines to the north , Aurich and Emden meet. The prisoners had to cover the distance between Engerhafe and Georgsheil on foot every day. From Georgsheil they were then transported by train to their workplaces in and around Aurich. The Engerhafe location was chosen for the external warehouse to be built because of the central location between Aurich, Emden and the north, the existing warehouse area of the Todt Organization and the good, also existing transport routes. After completing this work, the warehouse was initially empty.

prehistory

On 16 March 1942, the confiscated Todt Organization in consultation with the local peasant leader of the then vacant parish in Engerhafe Pfarrgarten and vicarage and built a warehouse. It consisted of two larger barracks with separate bedrooms and common rooms as well as cooking and washing facilities. This labor camp was not fenced off or guarded. Residents of Engerhafe were able to attend film screenings in the lounge. The inmates were Dutch labor service officers in the Wehrmacht who were deployed in Emden to build extensive air raid protection systems.

On August 28, 1944, Adolf Hitler ordered the entire North Sea coast to be fortified with several defensive lines and barriers, the so-called Friesenwall . Part of the plan was to declare the city of Aurich a fortress and secure it with an anti-tank ditch. This should be four to five meters wide and two to three meters deep. Due to the sloping walls, the bottom of the trench was only half a meter wide.

The military construction management was initially at the North Sea Marine Command in Wilhelmshaven together with General Command X in Hamburg. The technical construction management took over the Wehrmacht and the Organization Todt with 50 companies. On September 18, 1944, directed the High Command of the Armed Forces then the Corporate Office North Sea coast one based in Hamburg. The Admiral Deutsche Bucht , based in Wilhelmshaven, was employed for the immediate construction management . Due to the shortage of workers caused by the war, those responsible mainly used concentration camp prisoners from the Neuengamme camp for this work. The Neuengamme concentration camp then had seven satellite camps built to accommodate them; one of them was Engerhafe.

Engerhafe subcamp

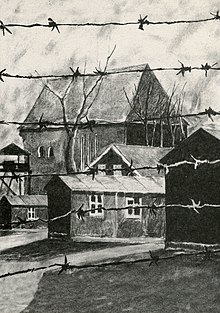

On October 21, 1944, the barrack camp was converted into a sub-camp of the Neuengamme concentration camp. For the satellite camp of the concentration camp, more land had to be confiscated, namely church land north of the pastorei, the playground of the Engerhafer elementary school and a strip of private land west of the Dodentwenter Weg. The first 400–500 inmates were transported to Engerhafe by train in mid-October. The transfer from the Neuengamme concentration camp, about 250 kilometers away, took between 20 and 30 hours. This advance detachment, which mainly included prisoners with skilled manual skills, had to convert the barrack camp into a concentration camp within a few days under the supervision of SS members by significantly expanding the camp and building security systems. According to investigations by the Aurich public prosecutor's office, after completion the camp consisted of seven larger and some smaller barracks. These were provided with steep roofs for camouflage so that they looked like agricultural buildings from the air. Despite the cold and wet, the rooms were not heated. The hygienic conditions were bad. There was only one small, completely inadequate washroom in the camp, in which inmates could only wash their faces and hands superficially. A pit with a beam served as a toilet. The complex was secured by four watchtowers at the corners and a chain-link fence with barbed wire at the top, which was also illuminated at night.

After completion, the camp was then occupied with more prisoners. These arrived at Georgsheil train station - three kilometers from Engerhafe - in cattle cars and came from all over Europe. Most of the inmates were political prisoners from Poland, the Netherlands, Latvia, France, Russia, Lithuania, Germany, Estonia, Belgium, Italy, Denmark, Spain and Czechoslovakia. They were arrested as resistance fighters , hostages or forced laborers . As far as possible, the camp administration accommodated the prisoners according to nationality.

Originally, Engerhafe was set up as a temporary summer camp for up to 400 labor service workers. After the conversion into a concentration camp satellite camp, however, 2,000 to 2,200 prisoners lived here in three unheated barracks that were 50 meters long and eight to ten meters wide and only had room for beds. There were 40 beds in each barrack. There were three beds on top of each other, and two or three men slept on straw mats in each bed. This encouraged the spread of disease and vermin. A blanket was also available for each sleeping area. There was a narrow corridor between the rows of beds.

The hygienic conditions in the camp were so catastrophic that pests and diseases spread rapidly. "When the dysentery later got out of hand, it also happened that the liquid excrement flowed from the upper beds into the lower ones." The medical care was also completely inadequate. The only doctor among the prisoners had neither medicine nor bandages at his disposal.

The inhumane conditions under which the prisoners were housed soon claimed their first deaths. The first four inmates were buried on November 4th. Two days later ten inmates were already dead. The church chronicle of November 6, 1944 notes: “The barrack camp in the parish garden has been turned into a prison camp for some time and has been very busy. There have been deaths, ten to date. "

The prisoners' daily routine was something like this: SS guards woke the prisoners at 4 a.m. , after which they were given a piece of bread, some jam and 20 grams of margarine and sausage each for breakfast. The roll call followed. Then most of the inmates marched in rows of five hooked to the Georgsheil train station, from where they drove to Aurich in an open freight car. After this short break, there was another long march through Aurich to the workplace. There the weakened men did hard work: Using coal shovels unsuitable for this work, they dug holes up to two and a half meters deep in the tough clay soil, often standing up to their knees in the water for hours. The men had to work as long as it was light. Late in the evening we went back to Engerhafe. On the way back there were always brutal attacks by kapos , who had been prompted by the guards, on prisoners who could not keep the pace of the marching column because they were too exhausted. There, the inmates received a dinner, which mostly consisted of a water soup with cabbage and a few jacket potatoes.

The main task of the prisoners was the construction of an anti-tank ditch around the city of Aurich in connection with the construction of the so-called Friesenwall . On December 15, 1944, 500 seriously ill people were transported back to Neuengamme. When the remaining prisoners were transferred to Neuengamme on December 22, 1944, the camp was closed again. Ten days later, Aurich's all-round defense was considered complete. 188 people perished in the Engerhafe concentration camp between October and December 1944. Bloody diarrhea was given as the cause of death in the church records .

Warehouse organization

Headquarters

The Engerhafe concentration camp was headed by SS-Oberscharführer Erwin Seifert , one of the few ethnic Germans in a leadership position. Before he took over the post in Engerhafe, he was a member of the command staff of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp . After the subcamp was dissolved, he was allegedly head of the training department in the Neuengamme main camp.

Security guards

The camp's guards consisted of four men from the SS-Totenkopfverband, supported by 50–60 marines and some older army soldiers who were no longer fit for field service. Engerhafe was one of around 80 external commandos of the Neuengamme concentration camp and one of over 340 camps throughout the German Reich. The SS death's head units that provided guards in the camps were no longer sufficient to guard all these camps. In Engerhafe, this meant that only the camp commandant and a few Unterscharfuhrers belonged to the SS, while the guards consisted of soldiers from the Navy. Adolf Hitler had personally ordered their use in 1944. For their work in the camps, they were given makeshift training, including with drawings from a picture book for concentration camp guards.

Response of the population

It can be taken for granted that many people knew of the existence of the camp. Finally, the inmates were driven through the city on their way to their workplaces in Aurich. The Ostfriesland-Magazin reports that the citizens fearfully watched the train of prisoners - the so-called yellow crossers - from a distance and preferred to go into their houses because they could not stand the sight. An eyewitness from Aurich comments: “[...] that on the one hand they simply couldn't stand the sight, because it also made their guilty conscience and their feeling of powerlessness particularly clear. And on the other hand, because, as far as I can remember, this train gave off an unbelievable smell, a really bad smell cloud ”.

Due to protests from the population, the prisoners were finally given a wheelbarrow to transport the dead. Until then, they had had to drag them by their feet on the way back to the camp, as they no longer had the strength to otherwise transport the corpses. The head hit the pavement again and again.

But there are also reports of villagers occasionally slipping the prisoners with food. For example, the miller at Vosbergmühle in Aurich. A reception camp for the completely exhausted forced laborers from the Engerhafe satellite camp was built at this mill. The SS had confiscated one of the mill's stalls and, of course, had the keys too, so no guard was necessary. Exhausted prisoners were locked in the barn by the SS guards and had to rejoin the group in the evening. However, the miller had a duplicate key and thus managed to give the prisoners bread, tea or soup unnoticed. Elke Suhr continues to report on school children who gave the prisoners lunch through the camp fence that adjoined the school yard.

After 1945

The former camp manager Erwin Seifert, a Sudeten German SS man from Czechoslovakia, was brought to justice by the Aurich public prosecutor in 1966, but was never convicted. Four years after the start of the proceedings, the court dropped the proceedings because the allegations of murder were unprovable and the statute of limitations on other charges. The Cologne Regional Court finally sentenced him to several years in prison in 1972 for his offenses in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

The French tracing service had the bodies exhumed and identified in 1952. The cemetery inventory book of the Engerhafe parish, which lists the names, dates of birth and nationalities of the concentration camp inmates buried in the Engerhafer churchyard, was helpful. This enabled the tracing service to identify almost all of the bodies. Among the 188 dead who were buried in Engerhafe were: 68 Poles, 47 Dutch, 21 Latvians, 17 French, nine Russians, eight Lithuanians, five Germans, four Estonians, three Belgians, three Italians and one Dane each, a Spaniard and Czech. “During the exhumation it turned out that in the northern part of the field there were graves up to 1.70 m deep, while the bodies in the southern area were only covered with a 40-60 cm layer of earth. The first ten were still packed in five wooden boxes, the following only wrapped in roofing felt and wire, and the rest - obviously the funeral material was completely used up - were buried in paper sacks or completely naked. "

The French and some of the Dutch were transferred to their homeland after their identification, the other identified Dutch came to the Heeger cemetery in Osnabrück in 1954. From there they were reburied in 1955 in the Stoffeler cemetery in Düsseldorf. The remaining dead were buried again in the Engerhafer cemetery.

The barracks were looted immediately after the end of the war. There are no photos from the camp. Only the sparse remains of the earth-filled walls of the latrine pit are visible today. It is no longer possible to determine when the other buildings were demolished.

Only remnants of the trenches built around Aurich are visible today, for example in the Heikebusch and in the Finkenburger wood. The majority of interned German soldiers had to fill in after the end of the war in the spring and summer of 1945.

memorial

Shortly after the end of the war, the association of those persecuted by the Nazi regime set up a memorial in the cemetery of the Engerhafe parish, which surrounded it with a low hedge. At that time, a flat memorial stone on the north side in front of the bell tower was marked: “Rest here?.?.?. Victims of Fascism ”.

In 1989 three more memorial stones were erected. The names of the 188 victims of the camp are immortalized on the two outer memorial stones. The middle memorial stone bears the inscription: “From October to December, the ENGERHAFE KOMMANDO AURICH-NEUENGAMME concentration camp was located in our village. Up to 2000 people who were employed in the construction of fortifications around Aurich were held prisoner in this camp. 188 of them died due to the inhumane living conditions. They were buried in a mass grave in the cemetery. The French tracing service - Dêlêgation Générale pour l'Allemagne et l'Autriche - Comité de Coordination de Recherche et d 'Exhumation, Göttingen - had the corpses exhumed in 1952 and buried in individual coffins. Some of the dead were returned to their home countries or reburied in other cemeteries. They were our brothers. "

In 2003, the municipality of Südbrookmerland , to which Engerhafe has belonged since 1973, began to make the last remaining part of the camp - the floor plan of a latrine pit - visible again and to integrate it into the memorial. There are plans to set up a memorial for the concentration camp in the form of a history house. However, this has not yet been decided in the Südbrookmerland municipal council.

The painter Herbert Müller has dealt with this camp in his art since 1989. A series of paintings and drawings were created, which reconstruct the situation from 1944 with artistic means, depict the situation of the captured people and incorporate documents, death notes and the excavation report of the Allied Commission on the finds from the mass graves. The basis for the work are stories from contemporary witnesses, former prisoners from Engerhafe and Aurich, the report by Martin Wilken, documentation material from the Allied Commission from 1952 and on-site graphic studies.

literature

- Manfred Staschen: The labor and prison camps around Aurich and the subcamp in Engerhafe . In: Herbert Reyer, City of Aurich (ed.): Aurich in National Socialism (= treatises and lectures on the history of East Frisia , vol. 69). 2nd edition, Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 1993, ISBN 3-925365-49-4 .

- Elke Suhr: The concentration camp in the parish garden. A tank ditch command for the Friesenwall Aurich-Engerhafe 1944. Library and information system of the University of Oldenburg, Oldenburg 1984, ISBN 978-3-8142-0097-2 .

- Martin Wilken: Barracks in the parish garden. In: Heimatkunde and Heimatgeschichte , supplement to the Ostfriesische Nachrichten , 4/1982.

- Martin Wilken: The Engerhafe concentration camp. Aurich-Neuengamme command .

- There are hardly any traces of the Engerhafe concentration camp , in: Ostfriesische Nachrichten of January 16, 2004.

- Imke Müller-Hellmann : Disappeared in Germany. Life stories of concentration camp victims. In search of traces through Europe , Osburg Verlag, Hamburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-95510-060-5

- Werner Juergens: Eleven out of one hundred and eighty-eight. In: Ostfriesland Magazin , issue 11/2015, p. 32 ff.

Web links

- Association Concentration Camp Memorial Engerhafe e. V.

- Aurich-Engerhafe on the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial website (with a map of the area)

- East Frisian Landscape / Engerhafe Concentration Camp (PDF; 48 kB)

- Guide No. 62 on the construction of the Friesenwall

- Drawing of the camp

Individual evidence

- ↑ Engerhafe Church: 1944 Church chronicle of the concentration camp satellite camp

- ↑ a b c d e Manfred Staschen: The labor and prison camps around Aurich and the Engerhafe concentration camp . In: Herbert Reyer (Ed.): Aurich in National Socialism. Pp. 421–445, here p. 438.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Association of the Engerhafe Concentration Camp Memorial: The Engerhafe Concentration Camp , viewed on June 4, 2013.

- ^ A b Manfred Staschen: The labor and prison camps around Aurich and the Engerhafe concentration camp . In: Herbert Reyer (Ed.): Aurich in National Socialism. Pp. 421–445, here p. 440.

- ^ A b c Elke Suhr: The concentration camp in the parish garden. A tank ditch command for the Friesenwall Aurich-Engerhafe 1944. Library and information system of the University of Oldenburg, Oldenburg 1984, ISBN 978-3-8142-0097-2 .

- ^ Helga Schütt et al.: East Frisia in National Socialism. Materials and instructions for teaching. Ostfriesisches Kultur- und Bildungszentrum, Aurich 1985, p. 216.

- ^ A b Manfred Staschen: The labor and prison camps around Aurich and the Engerhafe concentration camp . In: Herbert Reyer (Ed.): Aurich in National Socialism. Pp. 421–445, here p. 444.

- ↑ a b Eva Requardt-Schohaus: The repressed autumn of Engerhafe . In: Ostfriesland Magazin , issue 11/1994, p. 79.

- ^ Association of the Engerhafe Concentration Camp Memorial: List of the dead , viewed on June 4, 2013.

Coordinates: 53 ° 29 '14 " N , 7 ° 18' 55" E