Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge ( Khmer ខ្មែរក្រហម Khmêr-krâhâm; French Khmers rouges ) were a Maoist - nationalist guerrilla movement that came to power in 1975 under the leadership of Pol Pot in Cambodia and ruled the country as a totalitarian state party until 1979 . Their name is derived from the majority ethnic group of Cambodia, the Khmer . The Khmer Rouge wanted to transform society into an agrarian communism by force . This process also included the almost complete displacement of the capital's populationPhnom Penh and culminated in the genocide in Cambodia , which gained worldwide fame. By the end of their rule in 1979, the Khmer Rouge killed around 1.7 to 2.2 million Cambodians ( Khmer and members of ethnic and religious minorities ) according to the most widely spread estimates .

After their violent overthrow and the smashing of their regime by Vietnamese invasion troops , the Khmer Rouge became an underground movement again and received support from various countries, including Western countries , in their fight against the Vietnamese occupying power and the puppet regime it had installed , until they finally dissolved in 1998. A legal review had not taken place to date. The UN only began to push for a legal review in the 1990s and set up the Khmer Rouge tribunal . Due to a conflict of interest between the UN and the government of Cambodia, the first process did not formally take place until 2007.

Origins

The percentage of the rural population without real estate in Cambodia had risen from 4 to 20% in the years 1950-1970 and increased further in the course of the Cambodian civil war . The Khmer Rouge recruited mainly from this group, and especially the young people without ties to the village community or land ownership. On the other hand, border shifts under the colonial rule of French Indochina had created significant minorities in Cambodia, which had been relatively ethnically homogeneous until then, such as the Vietnamese and Muslim Cham , who were poorly integrated and were particularly severely persecuted during the later genocide for nationalist reasons.

The Khmer Rouge had its origins in the Communist Party of Cambodia , which emerged from the Indochinese Communist Party in 1951 and initially called itself the Revolutionary People's Party of the Khmer (RVPK) and later the Labor Party of Kampuchea (WPK). By 1954, under Sơn Ngọc Minh and Tou Samouth, over 1,000 party members had been won and, under the supervision of Việt Minh, the Khmer Issarak militia was expanded to over 5,000 men. In the left wing of this militia, whose member Norodom Sihanouk disparagingly referred to as Khmer Viet Minh , later leadership cadres of the Khmer Rouge such as Ta Mok and Keo Meas were found. Prince Sihanouk, who became sole ruler after a rigged election victory in 1955, suppressed the political opposition, so that a third of the RVPK members and many “Khmer Viet Minh” fled to Hanoi . In addition, Cambodia had achieved independence with the Indochina Conference , with which many fighters saw their goals as achieved and the Khmer Issarak almost completely dissolved. While the older party cadres, who were orientated towards Vietnam and mostly close to the people, were particularly severely persecuted by the secret police, the younger generation, who came from better backgrounds and often had an academic education, were exempt from the repression. A circle of former students from Paris around Pol Pot therefore gained influence in the RVPK at this time and took over the party leadership in early 1963 after the murder of Samouth, which probably goes back to them. This went underground soon afterwards, so that from 1967 a communist guerrilla movement against the regime of Sihanouk emerged in the countryside.

In September 1966, the WPK renamed itself to the Communist Party of Kampuchea (KPK), which Pol Pot intended to signal a distancing from Hanoi and a rapprochement with the Communist Party of China . On January 17, 1968, there was a skirmish with government forces during the Samlaut uprising , which was later celebrated by the Khmer Rouge as the birth of their military wing. At the time the armed wing was officially founded in March 1969, it numbered almost 800 guerrillas and grew to 40,000 by 1972.

By 1970, Sihanouk had kept Cambodia out of the region's devastating crises (the Vietnam War and its expansion to Laos ) through skillful diplomacy, and the country was considered one of the more politically stable in Southeast Asia. It was a thorn in the side of the United States that the Vietnamese FNL (Viet Cong) fighting against the American troops in Vietnam used the eastern part of Cambodian territory as a transport route (including the Ho Chi Minh Trail ) and a retreat. The FNL supported the communist guerrilla movement in Cambodia. The group had renamed itself several times, which is why King Sihanouk used the collective term "Khmer Rouge" in the press for all groups in the left-wing camp, which then prevailed abroad; The Khmer Rouge never called themselves that. Even under Sihanouk's rule, the proxy war escalated in eastern Cambodia, particularly with the start of Operation MENU . In the border area with Vietnam, the Viet Cong , the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), the Khmer Rouge, the armed forces of Cambodia and the United States Air Force were now and were fighting each other .

After being overthrown by Lon Nol on March 18, 1970, Sihanouk went into exile in Beijing and allied himself with the communist resistance in the Front uni national du Kampuchéa (FUNK). As the Gouvernement royal d'union nationale du Kampuchéa (GRUNK), the Sihanoukists and the KPK formed a government in exile to which Khieu Samphan , Hu Nim and Hou Yuon belonged. As a national figure of identification, Sihanouk was able to mobilize the rural population in particular to a considerable extent for his purposes. Just two days after his fall, he called on the Cambodians to go into the forests and join the resistance, which many ordinary Khmer Rouge soldiers later described as the triggering moment for their recruitment. The admiration for Sihanouk was so great that even many monks stood up for the GRUNK cause. The revolutionary morality of these fighters, however, left a lot to be desired, and communist ideas such as rebellion against large landowners who hardly existed in Cambodia turned out to be a hindrance to further recruitment. Up until 1972, the NVA and the "Khmer Viet Minh" who had returned from exile in Vietnam waged the Cambodian civil war against Lon Nol, taking most of the northeastern provinces.

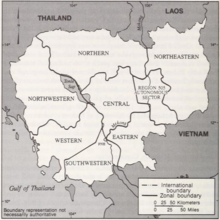

While the leadership around Pol Pot, also known as Brother No. 1, was oriented towards Beijing and was hostile to Vietnam, many local party cadres and the Khmer Issarak, especially in eastern Cambodia, still worked with the Viet Cong . The power center of the Khmer Rouge around Pol Pot and Nuon Chea , also known as Brother No. 2, began in 1971 with the political cleansing of the movement of Sihanoukists, Khmer Issarak and moderate, Pro-Vietnamese communists. In most regions of the country, this measure was completed by 1975. The murders were also directed against ethnic minorities within the party and militia, such as in the province of Koh Kong against the members of the Thai or in the province of Ratanakiri against the hill tribes . The State Department of the United States , which carried out one of the first studies on the Khmer Rouge based on interviews with refugees in 1973/1974, was able to identify this break within the movement between the hardliners of the Khmer Krahom (German: "Khmer Rouge") and the moderate forces of the Identify Khmer Rumdos (German: "Khmer Liberation"). An original faction of the Khmer Rouge, which had got into armed conflict with the KPK by the end of 1974, was the Khmer Saor (German: "White Khmer"), which consisted of Muslim Cham. As an autonomous militia in the ranks of the Khmer Rouge, these were only tolerated in the eastern administrative zone, but were dissolved by the central party leadership in 1974.

Army General Lon Nol, whose coup was supported by America, received substantial economic and military aid from Washington. With his approval, Richard Nixon and his Foreign Secretary Henry Kissinger attempted to militarily clear Cambodia of the FNL. By extending the war against communist North Vietnam and the Viet Cong to Cambodian soil, the US sacrificed the integrity of the last independent state of Indochina . Their area bombing, which began with Operation MENU, claimed at least 200,000 lives, mainly civilians, and contributed to driving a large part of the population into the arms of the Khmer Rouge. From October 4, 1965 to August 15, 1973, American B-52 aircraft dropped a total of 2,756,941 tons and in 1973 alone twice as many bombs over Cambodia as over Japan during the entire Second World War (during the entire Second World War - including Hiroshima (15,000 tons) and Nagasaki (20,000 tons) - 2 million tons of bombs were dropped). Cambodia is half the size of Germany. The fact that Vietnamese and Americans carried their war to Cambodia partly explains the nationalistic and hateful course of the Khmer Rouge.

Rule of the Khmer Rouge

On April 17, 1975, Phnom Penh was captured by the Khmer Rouge, the " Democratic Kampuchea " proclaimed and the exiled Prince Norodom Sihanouk installed as head of state.

Most of the city's residents were happy that the fighting had ended and cheered the invading troops. A large number of the fighters consisted of child soldiers , who at that time knew nothing but a life as a soldier.

Sentiment quickly turned when Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge began establishing a terror regime. On April 4, 1976, Norodom Sihanouk was deposed as head of state for his criticism of the course of the Khmer Rouge and placed under house arrest, Khieu Samphan was appointed as the new head of state and Pol Pot as head of government.

confidentiality

A peculiarity of the rule in Cambodia that distinguished it from the other dictatorships was the complete secrecy of the party and leading functionaries. They hid behind an alleged organization called Angka (short for angka padevat , "revolutionary organization"). Pol Pot made his first public appearance about a year after taking power in March 1976 as "worker on a rubber plantation". Pol Pot did not have a biography published, there were no collections of texts and only a few photos of him. Many Cambodians only found out about the identity of their head of government after he was overthrown.

Ideology and reality

Pol Pot was already attached to communist ideas as a young man and joined the Communist Party of Cambodia at the age of 18 and a little later, as a student in Paris, the Communist Party of France . In addition to the corruption of the Lon-Nol regime, he saw the causes of the poverty in Cambodia in the difference between town and country. So he believed he had to strengthen the peasantry and destroy everything urban.

The Khmer Rouge orientated itself towards Maoism, but showed clear differences in the ideological orientation towards the People's Republic of China. Central elements of communism such as industrial progress, mechanization and the proletariat as revolutionaries were missing, whereas the peasantry was glorified and the top leadership acted in extreme secrecy, even when they held state power. Because of these characteristics, the rule of the Khmer Rouge was also referred to with the political catchphrase Stone Age Communism.

The immediate deportation of the urban population to the country's rice fields transformed Phnom Penh, which previously had more than two million inhabitants, into a ghost town within a few days , and the provincial capitals were also depopulated. During this “long march”, which lasted up to a month, thousands of people (especially the elderly and children) died as a result of the exertion.

Soon every survivor was turned into a worker and forced to wear uniform black clothing that was supposed to eliminate any individuality. The Khmer Rouge spokesmen heralded the beginning of a new revolutionary age in which all forms of oppression and tyranny would be abolished.

In the first months of this revolutionary era, the country turned into a gigantic labor and prison camp. Daily working hours of twelve hours or more were not uncommon, and every step of the workers was monitored in such a way that almost everyone feared for his life. Those who were late for work could be executed on suspicion of sabotage . Talking while working was forbidden.

Money was abolished, books were burned , teachers, traders and almost the entire intellectual elite in the country were murdered in order to bring about the agrarian communism that Pol Pot had in mind. The intended relocation of economic activity to the countryside caused it to come to a complete standstill, as industrial and service companies - banks, hospitals, schools - were also closed.

Furthermore, the Khmer Rouge forbade any practice of religion. The Pol Pot regime destroyed hundreds of Buddhist monasteries, Christian churches and mosques as part of its efforts to eradicate the religion.

In 1976, Pol Pot set up a four-year plan to remove all class differences and lead the country into a "prosperous communist future." The agricultural productivity of Cambodia should be tripled in order to obtain the necessary foreign exchange through food exports. But this goal was not achieved, as the economic infrastructure was largely destroyed and the farm workers had to get by to a large extent without tools.

The supply of food also collapsed due to bad planning and mismanagement. Fearing reprisals, local executives falsified the harvest reports. The income was nevertheless taken away. Lack of food and forced labor as well as a lack of medical care led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands. Many of the executives responsible were arrested and killed for sabotaging the four-year plan.

Mass murder

So-called mass cleanups were carried out at the same time . Anyone suspected of collaborating with foreigners was murdered with spouses and children. Not only Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge blamed minorities, especially Vietnamese and foreigners, for the plight of Cambodia. The Vietnamese were not only unpopular because they had carried the war to Cambodia, but also because - brought into the country by the French during the French colonial rule in Indochina for administrative tasks - they represented a symbol for many of the country's foreign control. In addition, the Khmer Rouge claimed the Mekong Delta (Kampuchea Krom) for Cambodia, which, as Cochinchina, had fallen to Vietnam through the colonial rule of the French .

The “ bourgeoisie ” was “abolished”, and in order to be a “bourgeois” it was often enough to be able to read or speak a foreign language (especially French). Under the dictatorship of the Khmer Rouge, opposition members such as monarchists and supporters of the Lon-Nol regime and their spouses and children were killed en masse, but also those communists who had returned to Cambodia shortly before the takeover of power from Vietnam.

During the four-year reign of terror, an estimated 1.7 to 2.2 million people were killed in death camps or died while doing forced labor in the rice fields (out of a total population of just over seven million, which is a quarter to over 30%) . Seven out of a total of 15,000 to 30,000 prisoners survived in the notorious “ Security Prison 21 ” in Phnom Penh, which was under the management of Kaing Guek Eav , who was known under his pseudonym “Duch” (also “Dëuch” or “Deuch”) . Those who did not die of torture there were killed in the killing fields outside the city gates.

The mass purge is also known as autogenocide , since the government's extermination measures were aimed at its own people. Members of the Vietnamese minority, the indigenous Muslim Cham and the hill tribes were also affected by mass murders . The rights of these and other ethnic groups were fundamentally disregarded by the Pol Pot regime. A government document of the Democratic Kampuchea published in 1977 found that the minority population was only 1% when it was actually 20%. The hill tribes were called “Khmer Loeu” (German: “Upper Khmer”) and the Cham were called “Islamic Khmer”. While David P. Chandler and Michael Vickery in their works on the recent history of Cambodia classified the Pol Pot regime as chauvinistic , but did not speak of a genocide in this context, Ben Kiernan was the first historian to expressly express the minority policy of the Khmer Rouge referred to as ethnic cleansing . In addition to the Cham and Vietnamese, the Chinese minority also fell victim to the Khmer Rouge, so that the number of ethnic Chinese decimated from 430,000 to 215,000. In this case, the cause of the genocide lies less in the racism of the KPK leadership than in the social structure of the Chinese population group: Since the Chinese lived predominantly in the cities and were often wealthier and more educated than the average population, they were particularly often called New people deported to the countryside. Since, unlike many Khmer New People who came from villages or had relatives there, were not used to hard field work and the hardships, they died particularly often of exhaustion or illness. Many Chinese were also identified as bourgeois intellectuals and murdered. The mass murders of the Vietnamese and Cham were expressly described as genocide in the later criminal proceedings against members of the Khmer Rouge .

Reports of the atrocities committed by the Khmer Rouge sparked discussion until they were ousted. The accounts of John Barron and Anthony Paul, and Father François Ponchaud , who first wrote about mass murders in Cambodia in his 1977 book Cambodge - année zéro , have not been presented as objective by western leftists such as media critic Noam Chomsky . Chomsky and Edward S. Herman in The Nation on June 6, 1977 said Chomsky and Edward S. Herman in The Nation on June 6, 1977 protested that the press attention paid to the reported human rights violations from Cambodia was disproportionate to the atrocities committed by the Americans in Cambodia and Vietnam , his criticism at the time was tantamount to relativizing the reign of terror of the Khmer Rouge. His criticism should rather be seen as a refutation of the portrayal of Cambodia as a "meek country" that was suddenly thrown into the abyss by the Khmer Rouge in 1975.

Casualty numbers

To date, a number of mass graves with a total of around 1.39 million corpses have been discovered, excavated and evaluated in the country. Various studies differ in their assessment of the total number of victims between 740,000 and 3,000,000. Most of them range between 1.4 million and 2.2 million, with half the cause of death being executions (such as shooting, slaughtering, decapitation with field hoes and suffocation with plastic bags; small children were smashed against trees) and the other half death from a lack of food and disease is accepted.

Disempowerment and guerrilla warfare

On December 25, 1978, troops of the reunified Vietnam marched into Cambodia after the border incidents initiated by the Khmer Rouge with the aim of overthrowing the Pol Pot regime and installing a Pro-Vietnamese government. This happened as early as January 1979 when the United Front for National Salvation overthrew the Pol Pot regime and appointed Heng Samrin as the new head of government . He was a former member of the Khmer Rouge, who had fled to Vietnam in May 1978 for fear of the internal party purges. Three days after the Vietnamese marched into Phnom Penh, he proclaimed the People's Republic of Kampuchea . Pol Pot went underground and Norodom Sihanouk went into Chinese exile again. Various western states, including the Federal Republic of Germany and the USA as well as the neighboring country Thailand - traditionally rivaling Vietnam - protested against the invasion.

The subsequent guerrilla tactics of the Khmer Rouge and the constant food shortage led to the mass exodus of Cambodians to Thailand. At the same time, the Thai government was - despite all ideological differences - one of the most important supporters of the Khmer Rouge, as it was seen as the most important opponent of the Vietnamese occupying power and the Pro-Vietnamese and pro-Soviet regime in Phnom Penh. The Thai government of Kriangsak Chomanan declared that it would continue to recognize the Pol Pot regime as the only legitimate government in Cambodia and offered the leaders of the Khmer Rouge safe passage through Thai territory. Thailand allowed the Khmer Rouge to operate from bases on its national territory and left them partly to organize the refugee camps in the Thai-Cambodian border area. Thai government officials encouraged the People's Republic of China to support the Khmer Rouge and supply them with weapons. They made it possible to transport the weapons to the Khmer Rouge and finance them by diverting aid funds actually intended for the civilian refugees and selling precious stones. The Thai Foreign Ministry under Siddhi Savetsila was in the lead . He described the military chief of the Khmer Rouge, Son Sen , as "a very good person".

Thailand also urged that the Khmer Rouge and two non-communist opposition groups - the FUNCINPEC ("National Front for an Independent, Neutral, Peaceful and Cooperative Cambodia") of Norodom Sihanouk and the anti-communist Khmer People's National Liberation Front (KPNLF) of former Prime Minister Son Sann - should form a joint government in exile. The Thai Foreign Minister Siddhi Savetsila traveled to Beijing to see Prince Sihanouk and threatened to stop the financial aid if the alliance did not materialize. Then the three groups formed the coalition government of the Democratic Kampuchea in June 1982, based in Kuala Lumpur , Malaysia , with Sihanouk as president and Khieu Samphan as foreign minister. This was recognized by the United Nations as the legitimate representation of Cambodia and took the Cambodian seat in the UN General Assembly. The support of Thailand, China and the Western countries for the Khmer Rouge thus received a legitimate paintwork. The states of the Eastern Bloc , India and various third world countries, however, recognized the new government under Heng Samrin.

In September 1989 the Vietnamese troops withdrew from Cambodia, Heng Samrin remained in power. The Constitution of Cambodia was changed, the state was renamed again, this time to "State of Cambodia", and Buddhism was declared the state religion.

Norodom Sihanouk returned to Phnom Penh in 1990, and the Samrin government was further weakened by the actions of the resistance groups. On June 24, 1991, all Cambodian civil war parties including the Khmer Rouge signed a UN-negotiated ceasefire in Paris . The chairman of the transitional government, the “Supreme National Council”, was Norodom Sihanouk.

In 1992 the Khmer Rouge refused to allow itself to be disarmed under UN supervision in accordance with this Paris Peace Agreement. The civil war flared up again. Economic sanctions were imposed on the areas controlled by the Khmer Rouge and Thailand closed the borders with these regions.

In September 1993 the first free elections in 20 years were held under the supervision of the United Nations ; these were boycotted by the Khmer Rouge. At that time, the Khmer Rouge still numbered around 10,000 fighters and, after their official ban in July 1994, formed a counter-government in the province of Preah Vihear.Until 1995, they also abducted thousands of civilians to their concentration camps in the impassable jungle on the border with Thailand. The city of Pailin on the Thai-Cambodian border was under the control of the Khmer Rouge until 1997. Their leaders Nuon Chea ("Brother No. 2") and Ieng Sary ("Brother No. 3") lived there unmolested .

At the same time, however, the Khmer Rouge also collapsed internally. Generous offers from the government made it possible for many members and leaders of the Khmer Rouge to submit to the government and, for the most part, to build a new life for themselves. In 1997 Pol Pot was ousted from his leadership position as "Brother No. 1" by the Khmer Rouge, now under the leadership of Oung Choeun alias Ta Mok , the "butcher" or former head of the Southwestern Zone of Democratic Kampuchea , notorious for his brutality and sentenced as a traitor to life imprisonment. At the beginning of March 1998, Ta Mok, accompanied by four of his followers, crossed the border to Thailand to face the authorities there. His party purges had cost the lives of tens of thousands.

Pol Pot died on April 15, 1998 under unexplained circumstances in Anlong Veng in northern Cambodia. Color photos were presented to prove his death.

On December 25, 1998, exactly 20 years after the Vietnamese invasion, the former head of state Khieu Samphan and chief ideologist Nuon Chea were two of the last high-ranking leaders of the Khmer Rouge, after Pol Pot and his successor Ta Mok, the "brothers no. 2 and 3 ”to the Cambodian authorities and apologized for the crimes they committed. On December 6, 1998, according to the official version, the last fighting units surrendered. An agreement was negotiated between the government and the Khmer Rouge on the premises of the temple of Preah Vihear to take over a contingent of 500 Khmer fighters and officers in the national army.

Role of western states

The Khmer Rouge was recognized by the United Nations as the legitimate political representative of Cambodia even after its disempowerment as a result of the Vietnamese occupation, as some Western states, in particular the United States, refused to legitimize the Vietnamese occupation. In this context there were also statements such as Margaret Thatcher:

“So, you'll find that the more reasonable ones of the Khmer Rouge will have to play some part in the future government, but only a minority part. I share your utter horror that these terrible things went on in Kampuchea. "

“So you will find that the more sensible of the Khmer Rouge will have some role to play in the future government, but only a minor role. I share your utter horror that these terrible things have happened in Cambodia. "

Sweden, on the other hand, distanced itself from the Khmer Rouge after many Swedish citizens had asked for it.

It can be assumed that the Khmer Rouge guerrillas in their fight against the Vietnamese occupying power and against the government, which was supported by them and elected by the Cambodian citizens, were also supported by covert arms deliveries from the west. For example, they used anti-tank weapons from the West German company MBB in the fight against government troops. In addition, the Khmer Rouge and its allies are known to have received training in the use of landmines and other weapons by the British Special Air Service . The mines laid by the guerrillas are still a significant problem for the population decades later. By 2007, landmine accidents affected around 15% of Cambodians.

presence

According to observers, the Khmer Rouge are still active underground in Cambodia, but no longer pose an immediate threat to the existing state.

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal , an ad hoc criminal court originally planned on the model of the ICTY in The Hague and the ICTR in Arusha , but now not under UN law, began its work on July 31, 2007 - after already in August 1979 in Phnom Penh a People's Tribunal of the Pro-Vietnamese Government, citing the London Statute of 1945 , had convicted Pol Pot and his deputy prime minister and foreign minister, Ieng Sary, for their crimes against humanity . Here the western world reacted differently under the leadership of the USA: With this “show trial” and “propaganda theater” the Cambodian communists wanted to divert attention from the military intervention of Vietnam.

The tribunal was only sought for members of the top management ranks, as too many politicians in today's Cambodia, such as B. the current Prime Minister Hun Sen , can look back on a red past. The period of time that is the subject of the negotiations is also limited to the conquest and fall of the capital, otherwise the USA, China, Vietnam and perhaps even the United Nations would have to sit in the dock.

Some former Khmer Rouge converted to Christianity, hoping for more forgiveness here, including the former commander of Security Prison 21 in Phnom Penh, Duch. Most of the documents incriminating the Khmer Rouge originate from the prison.

Some surviving Khmer Rouge leaders such as Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan and Ieng Sary initially led a secluded life in Pailin and pretended to have known nothing. Khieu Samphan had published his memoirs with the intention of convincing the Cambodian people that he was not involved in the massacres, that he was only publicly representing the country as president and only recently the truth about the atrocities during the regime of his colleagues have experienced. In the event of an indictment, he wanted to be represented by the French lawyer Jacques Vergès , whom he knew from his student days in Paris and who is also responsible for the defense, inter alia. from Klaus Barbie and Carlos . Ieng Sary had already officially converted to a democrat in 1996 and was ready to testify before a commission of historians in the event that he was assured of impunity. A commission similar to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa was assumed here. This was not in line with the plan for the trial to try the main culprits. All three were eventually arrested and handed over to the Khmer Rouge tribunal. Nuon Chea was arrested on September 19, 2007 in the Cambodian jungle. On November 12, 2007, Ieng Sary and his wife Ieng Thirith were arrested and a few days later, on November 18, 2007, Khieu Samphan was arrested.

The evidence is secured. The meticulousness of the Khmer Rouge and Duch's hasty flight during the invasion of the Vietnamese make it possible to trace the crimes of the Khmer Rouge on the basis of around 500,000 pages of documentation material. 8,000 mass graves were located. Of the estimated 1.5 million deaths for which the protagonists of the terrorist regime are held responsible, 31% are due to executions or torture, the remainder result from the consequences of malnutrition, forced labor, lack of medical care, etc.

The Cambodian National Assembly ratified an agreement with the United Nations on October 4, 2004, which makes the Khmer Rouge Tribunal possible. Its implementation was initially questionable, among other things because the US refused to contribute to the estimated costs of 65 million US dollars. In the meantime, however, the UN member states have succeeded in securing the tribunal financially. The issue of where the judges should come from could also be settled. Unlike the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia , the majority of judges will be Cambodian and Cambodian law will apply. In order to prevent bribery and the like, the judgment should only be valid if at least one foreign judge agrees.

On February 17, 2009, the first trial before the Khmer Rouge Tribunal opened. Five Khmer Rouge leaders were charged, including the former head of Security Prison 21 , Kaing Guek Eav , aka "Duch," who ran the infamous Tuol Sleng Prison, also known as the "Security Bureau" S-21, from March 1976 to early 1979 and is charged with crimes against humanity. On July 26, 2010, the tribunal sentenced Kaing Guek Eav to 35 years' imprisonment, part of which has already been served and the 67-year-old only has to serve 19 years. During the appeal hearing on February 3, 2012, the sentence was increased to life imprisonment.

On August 7, 2014, the Tribunal pronounced the verdict in the trial of Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan. Both were sentenced to life imprisonment for crimes against humanity .

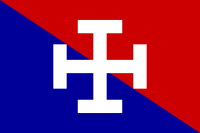

Flag of the Khmer Rouge

Little is known about the symbolism of the Khmer Rouge. The only symbol of their organization was probably a simple red flag , possibly partly with a hammer and sickle . In the west, the Khmer Rouge was incorrectly assigned a blue and red flag with a white cross . However, it was the flag of the Montagio ( French for Mouvement National , "National Movement"), a small nationalist student movement. Immediately before the Khmer Rouge invaded Phnom Penh, its supporters stormed the Ministry of Information and pretended to be the Khmer Rouge. Due to the chaos in the city, this information has not been verified and its flag has therefore been assigned to the Khmer Rouge.

exhibition

- 2015: The Khmer Rouge and the aftermath. Documentation as artistic memory work , Akademie der Künste Berlin , Berlin.

Media reception

- The long way of hope (2017, director: Angelina Jolie ; based on the autobiographical novel by Loung Ung ).

- The missing image (original title: “L'image manquante”, France 2013, written / directed by Rithy Panh ); Documentation by the author and director about his childhood in a re-education camp of the Khmer Rouge, original film material and animation with clay figures and dioramas.

- Enemies of the People (documentary, 2009, directed by Thet Sambath , Rob Lemkin).

- S-21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine (2003, directed by Rithy Panh ).

- Les Khmers rouges - The Khmer Rouge (documentary in three parts, France 2001, script / director: Adrian Maben).

- Part I: Pouvoir et terreur (Balance of Terror).

- Part II: Le mystère Pol Pot (The Pol Pot System).

- Part III: Crime sans châtiment (guilt without atonement).

- The Killing Fields (1984, director: Roland Joffé ; about the friendship between the American journalist Sydney Schanberg and his Cambodian colleague Dith Pran ).

- Die Angkar (documentary, 1981, 89 minutes, directors: Walter Heynowski and Gerhard Scheumann ).

literature

- Ariane Barth , Tiziano Terzani , Anke Rashatusavan: Holocaust in Cambodia. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1980, ISBN 3-499-33003-2 .

- Elizabeth Becker: When the War Was Over: Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge Revolution. PublicAffairs, New York (NY) 1998, ISBN 1-891620-00-2 .

- Daniel Bultmann: Violence and Order under the Khmer Rouge. In: Journal for Genocide Research. Volume 18, Issue 1, 2020, ISSN 1438-8332 , pp. 70–91.

- Daniel Bultmann: Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge. The creation of the perfect socialist. Schoeningh, Paderborn 2017, ISBN 978-3-506-78692-0 .

- Daniel Bultmann: Irrigating a Socialist Utopia. Disciplinary Space and Population Control under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-1979. In: Transcience. Volume 3, Issue 1, 2012, pp. 40–52 ( text link ; PDF; 383 kB).

- Daniel Bultmann: The revolution is eating its children. Lack of legitimation, educational violence and organized terror under the Khmer Rouge. International Asia Forum No. 42, May 2011, ISSN 0020-9449 ( Text-Link ; PDF; 295 kB).

- David P. Chandler : Brother Number One. A Political Biography of Pol Pot. Revised Edition. Silkworm, Chiang Mai 2000, ISBN 978-974-7551-18-1 .

- Susan E. Cook: Genocide in Cambodia and Rwanda. New Perspectives. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick / London 2006, ISBN 978-1-4128-2447-7 .

- Alexander Goeb, Helen Jarvis: The Cambodia Drama: God-Kings, Pol Pot and the Process of Late Atonement - Reports, Commentaries, Documents. Laika, Hamburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-9442-3350-5 .

- Karl D. Jackson (Ed.): Cambodia 1975-1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1989, ISBN 978-0-691-02541-4 .

- Ben Kiernan : The Pol Pot Regime. Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge. 1975-79. 2nd Edition. Yale University Press, New Haven (CT) 2002, ISBN 978-0-300-09649-1 .

- Andreas Margara : The Khmer Rouge Tribunal and the coming to terms with the genocide in Cambodia. Thuringian Cambodian Society, Heidelberg 2009 ( Text-Link ; PDF; 4.8 MB).

- Patrick Raszelenberg: The Khmer Rouge and the Third Indochina War (= communications from the Institute for Asian Studies Hamburg. No. 249). Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-88910-150-X .

- Manfred Rohde: Farewell to the Killing Fields - Cambodia's long road to normality. Bouvier, Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-416-02887-2 .

- Olivier Weber : Les Impunis. Un voyage dans la banalité du mal. Robert Laffont, Paris 2013, ISBN 978-2-221-11663-0 .

- Harry Thürk: If we have rice, we can have everything. Revised new edition. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Halle 2017, ISBN 978-3-95462-779-0 .

Web links

- Finally the chance for education and justice. Information from the Federal Foreign Office

- Hans Christoph Buch : Sorry, very sorry. In: The time . 10/1999

- Hans Michael Kloth: Interview with a mass murderer. In: Spiegel Online , one day .

- Armin Wertz : Curse of the Dead Years In: Friday . January 19, 2001

- Information from the Federal Foreign Office on the so-called Khmer Rouge Tribunal ( Memento from February 12, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- Documentation Center Cambodia

- private page: More information on the topic

- Meike Fries: Khmer Rouge Tribunal. The murderers live in hiding in the country. In: The time . November 22, 2011, accessed on November 23, 2011 (interview with Thet Sambath on the occasion of the opening of the trial against Nuon Chea).

- Rule of Terror: Liberation of Cambodia from Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge Deutschlandfunk Nova specialty program on the Khmer Rouge from January 4, 2019, contains, inter alia. Interviews with historians Andreas Margara and Bernd Stöver , as well as ARD correspondent Holger Senzel . Retrieved January 5, 2019

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kiernan : The Pol Pot Regime. 2002, p. 7.

- ↑ Kiernan: The Pol Pot Regime. 2002, pp. 5, 6.

- ↑ Bultmann: Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge. 2017, pp. 37, 38.

- ↑ Bultmann: Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge. 2017, p. 43.

- ↑ Kiernan: The Pol Pot Regime. Pp. 12-14.

- ^ Chandler : Brother Number One. 2000, p. 126.

-

^ Chandler: Brother Number One. 2000, p. 80.

Bultmann: Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge. 2017, p. 53. - ↑ Bultmann: Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge. 2017, p. 54.

- ↑ Bultmann: Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge. 2017, pp. 10, 11.

- ↑ Bultmann: Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge. 2017, pp. 55, 56.

- ↑ Bultmann: Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge. 2017, pp. 59, 60.

- ↑ Kiernan: The Pol Pot Regime. 2002, pp. 14-16.

- ↑ Kiernan: The Pol Pot Regime. 2002, pp. 69-80.

- ↑ Kiernan: The Pol Pot Regime. 2002, pp. 80-86.

- ↑ Kiernan: The Pol Pot Regime. 2002, pp. 65-67.

- ↑ Kiernan: The Pol Pot Regime. 2002, pp. 67, 68.

- ↑ Taylor Owen , Ben Kiernan : Bombs over Cambodia ( Memento April 15, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: The Walrus. Canada, October 2006, pp. 62-69. (PDF; 836 kB).

- ↑ Katja Dombrowski: A black day for Cambodia. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . April 15, 2005, archived from the original on December 18, 2013 ; Retrieved December 14, 2013 .

- ↑ Ben Kiernan: How Pol Pot Came to Power. Colonialism, Nationalism and Communism in Cambodia, 1930-1975. Yale University Press, New Haven (CT) 2004, ISBN 978-0-300-10262-8 .

- ↑ Angelika Königseder: The Pol Pot Regime in Cambodia . In Wolfgang Benz (ed.): Prejudice and genocide: ideological premises of genocide . Böhlau, Vienna 2010, ISBN 978-3-205-78554-5 , p. 174.

- ↑ Steven Erlanger: The Endless War. The Return of the Khmer Rouge. In: New York Times . March 5, 1989.

- ↑ Susanne Mayer : Finally! The trials against the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia can begin. In: The time . June 21, 2007, accessed January 30, 2017.

- ↑ Kiernan: The Pol Pot Regime. 2002, pp. 251-252.

- ↑ Kiernan: The Pol Pot Regime. 2002, pp. 288-296.

- ↑ Pol Pot's vice demands the end of the process. In: Zeit Online . June 27, 2011.

- ^ Noam Chomsky , Edward S. Herman : Distortions at Fourth Hand. In: The Nation . June 6, 1977.

- ↑ Bruce Sharp: Counting Hell: The Death Toll of the Khmer Rouge Regime in Cambodia.

- ^ Cook: Genocide in Cambodia and Rwanda. 2006, pp. 82-83.

- ^ Duncan McCargo , Ukrist Pathmanand: The Thaksinization of Thailand. NIAS Press, Copenhagen 2005, p. 33.

- ^ Cook: Genocide in Cambodia and Rwanda. 2006, p. 83.

- ↑ a b Chanthou Boua: Thailand Bears Guilt for Khmer Rouge. In: The New York Times. March 24, 1993, p. 20.

- ^ A b Cook: Genocide in Cambodia and Rwanda. 2006, p. 84.

- ↑ Cambodia's Pol Pot confirmed dead ( memento of March 8, 2008 in the Internet Archive ). In: CNN . April 16, 1998.

- ↑ John Pilger: The Long Secret Alliance: Uncle Sam and Pol Pot. 1997.

- ↑ John Pilger: Tell me no lies. Jonathan Cape, 2004.

- ↑ Khmer Rouge using Missiles made in West. In: New Straits Times . March 12, 1994.

- ↑ Michael Sontheimer: The murderers return. In: The time. January 12, 1990.

- ↑ John Pilger: How Thatcher gave Pol Pot a hand. ( Memento of January 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) In: New Statesman . April 17, 2000.

- ↑ Craig Guthrie: Trial and error in Cambodia. In: Asia Times Online . February 19, 2009.

- ↑ Ex-chief ideologist of the Khmer Rouge arrested ( Memento from February 22, 2009 in the Internet Archive ). In: AFP . September 18, 2007.

- ↑ Nicola Glass: Ex-Head of State of the Khmer Rouge: Arrested in the sickbed . In: taz . November 19, 2007.

- ↑ Setareh Khalilian: Better a false peace than no peace? ( Memento from July 20, 2006 in the Internet Archive ). In: Menschenrechte.de (website of the Nuremberg Human Rights Center ).

- ↑ Sophie Mühlmann: Pol Pot's brutal executioner is now on trial. In: The world . February 17, 2009, accessed January 30, 2017.

- ↑ Convicted of torture chief of the Khmer Rouge. In: 20minuten.ch . July 26, 2010, accessed January 30, 2017.

- ↑ Lifelong for chief torture of the Khmer Rouge. In: orf.at . February 3, 2012, accessed January 30, 2017.

- ↑ Lifelong for aged butchers: Genocide tribunal condemns Khmer Rouge. In: n-tv.de. August 7, 2014, accessed January 30, 2017 .

- ^ Siegfried Ehrmann: Kampuchea - flag with a past. In: Spiegel Online , one day . April 13, 2008, accessed January 30, 2017.

- ↑ Philip Short: Pol Pot. Anatomy of a Nightmare . Henry Holt, New York 2004, ISBN 0-8050-8006-6 , p. 266 f. ( Limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ From discretion to horror. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . February 5, 2015, p. 12.