Democratic Kampuchea

| កម្ពុជាប្រជាធិបតេយ្យ | |||||

|

Kâmpŭchéa Prâcheathippadey |

|||||

| Democratic Kampuchea | |||||

| 1975-1979 | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Official language | Khmer | ||||

| Capital | Phnom Penh | ||||

| Form of government | People's Republic | ||||

| Government system | Maoist one-party system | ||||

| Head of state | 1975/76 Norodom Sihanouk , 1976–1979 Khieu Samphan | ||||

| Head of government | Pole pot | ||||

| surface | 181,040 km² | ||||

| currency | none, since money was abolished | ||||

| National anthem | Dap Prampi Mesa Chokchey | ||||

| Time zone | UTC + 7h | ||||

Democratic Kampuchea ( Khmer: កម្ពុជាប្រជាធិបតេយ្យ , Kâmpŭchéa Prâcheathippadey), in West Germany officially Democratic Kampuchea , wrongly Democratic Republic of Kampuchea , Democratic Republic of Cambodia , Republic of Democratic Kampuchea , was the official name of Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. The state was founded after the Maoist nationalist Khmer Rouge defeated the pro-Western Khmer Republic led by Lon Nol . The administrative bodies were called Angkar Loeu ("Upper Organization"). The leadership of the Communist Party of Cambodia (KPK) called itself Angkar Padevat at the time . The leader of the Khmer Rouge was Pol Pot , its goal was to establish a self-sufficient peasant state, and numerous human rights violations (including large-scale forced labor and executions of potential opponents), collectively known as the genocide in Cambodia , occurred under its rule .

After massacres of ethnic Vietnamese and attacks by the Khmer Rouge on Vietnamese villages, troops of the Vietnamese People's Army marched into the area of Kampuchea and Cambodia in 1979 and after a few days proclaimed the People's Republic of Kampuchea (VRK) with a Provincial government made up of Cambodians in exile. The forces of the Khmer Rouge regrouped along the border with Thailand and retained the structure of the DK state in the regions they controlled. Most western states continued to recognize the Khmer Rouge regime as the rightful government of the country.

history

Civil war and establishment of the regime

In 1970, Norodom Sihanouk, who had ruled first as king since 1955 and as sole ruler from 1960, was deposed as head of state by the National Assembly under the leadership of Prime Minister Lon Nol . Sihanouk opposed the new government in an alliance with the Khmer Rouge. Because of the Vietnamese occupation of East Cambodia, the massive area bombing of the country by the US armed forces and based on Sihanouk's reputation, who was revered as god-king by the rural population , the Khmer Rouge was able to establish itself as a peace-loving party and as part of one supported by the majority of the population Represent coalition. With great support from the rural population, they were able to take the capital Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975 . For the time being, Norodom Sihanouk continued to serve as a representative figure of the new government.

Immediately after the fall of Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouge evacuated the approximately 2.5 million inhabitants (including 1.5 million war refugees) so that the arterial roads clogged with resettlers. The city was quickly almost deserted. The Khmer Rouge justified the evacuations by stating that it was not possible to organize the transport of sufficient food for the city's population of between 2 and 3 million. Therefore, it was argued that it is not the food that needs to be brought to the people, but the people to the food. They also spread rumors that American planes were about to bomb the city.

Similar evacuations were carried out in Battambang , Kampong Cham , Siem Reap , Kampong Thom and other cities. The Khmer Rouge wanted to transform the country into a nation of farm laborers, where corruption and the “parasitism of city life” would be completely eradicated.

Immediately after the victory of the Khmer Rouge in 1975, there was a skirmish with Vietnamese troops. Other incidents occurred in May 1975. In June, Pol Pot and the new Foreign Minister from South Vietnam, Ieng Sary , traveled to the Vietnamese capital Hanoi . They proposed a friendship treaty between the two countries, which was received rather coldly by the leaders of Vietnam.

Decline

After increasingly provocative border violations by the Khmer Rouge, the Vietnamese government decided in the spring of 1978 to support the inner-Cambodian resistance to the Pol Pot regime, with the result that the east of the country developed into a focal point of the uprising. The war hysteria took on strange flowers in Democratic Kampuchea : For example, in May 1978 - on the eve of the So Phims uprising in the East Zone - Phnom Penh Radio declared that if every Cambodian soldier kills 30 Vietnamese, only 2 million soldiers would be required to raise the entire Vietnamese population of 50 million to destroy. Apparently the leadership in Phnom Penh was seized by immeasurable territorial ambition: for example, they wanted to recapture the Mekong Delta , which they saw as Khmer territory.

After the May uprising, the massacres of ethnic Vietnamese and their sympathizers by the Khmer Rouge increased in the east. Some sources claim that Minister Vorn Vet, who allegedly sympathized with Vietnam, attempted a coup in the late summer of 1978. It is not clear whether this attempt really took place. Other sources point out that other than a torture-forced confession from Vorn Vets, there is no solid evidence of such activity. What is certain is that in the final months of 1978 there was another wave of cleansing within the Khmer Rouge, which Vorn Vet also fell victim to. It is often seen in connection with Pol Pot's paranoia , which, in view of an impending attack by Vietnam, has now also been directed against his own confidants.

In the second half of 1978 there were tens of thousands of Cambodian and Vietnamese exiles on Vietnamese territory. On December 3, 1978, Radio Hanoi announced the establishment of the United Movement for the Rescue of Cambodia (French Front uni national pour le salut du Kampuchéa , FUNSK). They were a heterogeneous group of communist and non-communist exiles held together by their opposition to the Pol Pot regime and their almost complete dependence on protection and support from the Vietnamese.

Vietnamese invasion

In the course of 1978 the acts of war by the Cambodians in the border region reached a level that the Vietnamese government could no longer tolerate. Vietnam decided on a military solution and began an invasion on December 22nd with the aim of overthrowing Democratic Kampuchea . Initially two divisions crossed the border, and from December 25th, 13 Vietnamese divisions with a total of around 150,000 soldiers were deployed, supported by the Air Force. Although the army of Kampuchea had been upgraded financially and materially by China, the Cambodian troops were so inferior to the Vietnamese in direct combat that Vietnam had already taken half of Kampuchea after two weeks. On January 7, 1979, Vietnamese troops took the capital, Phnom Penh.

The following day, the People's Republic of Kampuchea was proclaimed, which was considered a satellite state of Vietnam. The new government was supported by a strong Vietnamese military presence as well as civil Vietnamese government advisors. During the 1980s, the satellite government of the newly established People's Republic of Kampuchea was mainly occupied with organizing its own survival, rebuilding the economy and fighting the Khmer Rouge politically and militarily.

The Khmer Rouge initially withdrew to Thailand . For more than two decades, with the tolerance of the Thai government, they lived in several camps in the province of Trat, which is directly on the border with Cambodia, and from there carried out guerrilla operations against the Cambodian government until the 1990s .

Continued work as a government in exile

In June 1982 the coalition government of the Democratic Kampuchea was formed including the monarchist FUNCINPEC and the anti-communist-republican KPNLF , the Khmer Rouge (as the party of the Democratic Kampuchea ) continued to play the leading role. This government-in-exile continued to lead guerrilla campaigns against Cambodia with the support of China and the USA, among others, and acted as the legitimate government of Cambodia vis-à-vis international organizations. After the interim administration of the United Nations in Cambodia and the elections to the National Assembly in July 1993 , the Kingdom of Cambodia was internationally regarded as a legitimate government and the Democratic Kampuchea was isolated.

politics

Constitution

The drafting of a constitution for the Democratic Kampuchea dragged on over nine months. Although the leadership of the Khmer Rouge had laid down the main features of the future constitutional order in April 1975, the text of the constitution was not finalized until December 1975. After adoption on December 19, 1975, it was promulgated in January 1976.

legislative branch

Article 5 of the Constitution gave legislative power to the Assembly of Representatives of the People of Kampuchea. She represented the people, the workers, the peasants and the members of the army. The assembly had 250 members, 150 of whom represented the peasants, 50 the workers, and another 50 the army. The assembly of representatives should be elected every five years by general, direct, immediate and secret elections by the population (Article 6 of the Constitution). The elections took place in March 1976 without prior campaigning. The candidates were given; one of them was Pol Pot, who started as a laborer on a rubber plantation. It is doubtful whether the entire population could actually vote. According to one source, only workers in factories could vote, while farmers in the cooperatives were excluded from participating.

The only plenary session of the Representatives' Assembly took place from April 10-13, 1976 in Phnom Penh. At this meeting, the assembly adopted rules of procedure. Thereafter, the members should meet once a year. The day-to-day business was to be carried out by a standing committee of the meeting of representatives, to which ten members belonged. Nuon Chea was the chairman of the Standing Committee. The Standing Committee of the Representative Assembly was formally independent from the Standing Committee of the Communist Party of Cambodia , although several party officials were members of both committees.

After April 1976, contrary to its rules of procedure, the representative assembly did not meet again.

executive

Top government

According to Article 8 of the Constitution, the Executive was elected by the Assembly of Representatives of the People of Kampuchea.

After the only meeting of the representative assembly on April 14, 1976 the new government of the Democratic Kampuchea was presented to the public. The divisions were staffed as follows:

- Pol Pot (Prime Minister)

- Ieng Sary (Deputy Prime Minister, Foreign Minister)

- Vorn Vet (Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Economics; "Super Minister")

- Son Sen (Deputy Prime Minister, Defense; also: Head of the Intelligence Service)

- Hu Nim (Minister for Information and Propaganda)

- Thioun Thoeun (Minister of Health)

- Ieng Thirith (Minister for Social Affairs)

- Toch Phoeun (Minister of Public Works)

- Yun Yat (Minister of Culture and Education).

There were many family and personal ties between members of the government. The Minister of Social Affairs Ieng Thirith was the sister of Pol Pot's wife Khieu Ponnary , who, despite suffering from paranoid schizophrenia, nominally headed the National Women's Association in Democratic Kampuchea and was celebrated in 1978 as the "mother of the revolution". Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Ieng Sary was Ieng Thirith's husband and Pol Pot's brother-in-law. Defense Minister Son Sen had trained with Pol Pot in Paris in the 1950s. Son was married to Yun Yat, Minister of Culture and Education. From this and from other personal interrelationships, retrospective considerations derived the assessment that the Khmer Rouge was structured like a clan.

Some members of the leadership circle were killed in the political cleansing. Propaganda Minister Hu Nim was arrested around April 1977 and executed in July 1977 based on confessions he made under torture. “Super Minister” Vorn Vet was arrested, tortured and executed in November 1978, two months before the end of the Khmer Rouge regime. Both were accused of sympathy for their neighbor Vietnam, who are hostile to Kampuchea, and of preparing for a coup.

administration

A functioning state administration did not actually exist in the Democratic Kampuchea . In the period from 1975 to 1978, the Cambodian Communist Party , which partly appeared as Angka, was the de facto center of power in the country. With its sub-organizations, it reached social life right up to the local cooperatives.

Self-sufficiency and isolation

The Khmer Rouge pursued the goal of political and economic self-sufficiency. The party's leadership was dominated by the fear that Kampuchea could be worn out between its large neighbors Thailand and Vietnam. During the student years in Paris, Pol Pot, his future wife Khieu Ponnary, Ieng Sary and Ieng Thirith had contact with the Communist Party of Indochina , which was dominated by the Vietnamese. Already here they distanced themselves from the Vietnamese communists and saw the need for their own Cambodian line. In the following ten years this striving for independence from Vietnam developed into a xenophobia among the leading functionaries of the Khmer Rouge. From this, Khieu Samphan developed in his dissertation published in 1959 the idea of Cambodian autarky, which significantly shaped the economic, domestic and foreign policy of the Democratic Kampuchea . In his opinion, the owners of the Cambodian production facilities lived largely abroad and would also transfer their profits there. In order to ensure the economic development of the country, Cambodia must be cut off from foreign influence, and the profits must remain in the country.

Economic policy was aimed at ensuring the supply of the Cambodian population themselves and without resorting to imports from abroad. Pol Pot therefore declared agriculture to be the "basic factor" of the national economy in 1977; industry has to serve it.

In terms of foreign policy, the fear of a Vietnamese supremacy explains the long-running conflict between Kampuchea and Vietnam and ultimately the country's turn to China. Vietnam was under the influence of the Soviet Union in the late 1970s, while China pursued its own course critical of the Soviet Union and was also distant from Vietnam. China supported Kampuchea until the last days of the Pol Pot regime. The reason for this is often seen in China's efforts to maintain Cambodia as a buffer state between itself and Vietnam.

The striving for independence and self-sufficiency led to the breakdown of diplomatic relations with almost all states in terms of foreign policy. From 1975 onwards, Kampuchea only had contacts with a few countries in the socialist camp. Among them were the People's Republic of China as the most important ally, as well as the neighboring states of Laos , Thailand and Vietnam, as well as North Korea , Yugoslavia and Romania . Visits from foreign politicians were rare. Apart from Chinese delegations, there was only one visit by a representative from Burma and, in 1978, a visit by Romanian President Nicolae Ceauşescu .

It wasn't until the fall of 1978 that there were signs that Kampuchea might move away from its line of self-isolation. In December 1978 - a few weeks before the start of the Vietnamese invasion - the Khmer Rouge invited two journalists and a scientist from non-socialist countries for the first time. In an interview with Washington Post journalist Elizabeth Becker , Pol Pot claimed that the Warsaw Pact was against Cambodia after describing the Vietnamese threat . Some observers see it as a late attempt by Pol Pot, similar to the pro-Chinese and Moscow-critical Nicolae Ceaușescu, to arouse sympathy with the United States of America.

Social order

Officially, the social order of the Democratic Kampuchea was completely egalitarian. In practice, however, this was not the case: Members of the KPK, applicants for membership, level leaders of the poor rural hinterland who worked with Angka , and members of the military enjoyed a higher standard of living than the rest of the population . Given its radical revolutionary ideas, it seems ironic that under the leadership of the Khmer Rouge nepotism reached a level almost equivalent to that of the Sihanouk era. Due to the Cambodian culture, the intense secrecy, and the leadership's distrust of outsiders, especially the Vietnamese communists, family ties were very important. Greed was also a motive. Several ministries, such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Industry, were ruled by influential Khmer Rouge families and used for their private purposes. Service in the diplomatic corps was seen as a particularly profitable “ fief ”.

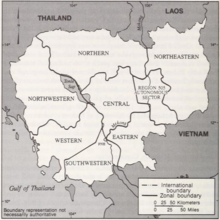

Administrative division

In 1975 the Khmer Rouge abolished all traditional Cambodian administrative districts. The previous provinces were replaced by seven geographical districts. This structure was based on the territorial division of the Khmer Rouge, as it had developed during the civil war from the fighting against the Khmer Republic under General Lon Nol (in brackets the respective secretary of the committee, i.e. head of the local government):

- the Northwest Zone (Ros Nhim aka Moul Sambath)

- the Northern Zone (Sae alias Kang Chap)

- the Northeast Zone (Ya aka Men San)

- the Eastern Zone ( So Phim aka So Vanna)

- the Southwest Zone ( Ta Mok aka Ek Choeun)

- the Siemreap special region No. 106 (until mid-1977)

- the capital special zone Phnom Penh ( Vorn Vet alias Penh Tuok, Sok Thuok)

In mid-1975 the western zone was split off from the southwest zone, and in 1976 the Kratie special region No. 505 was split off from the northeast zone (and placed under direct control of the central government). In mid-1977 the Northern Zone was divided into a Northern and a Central Zone, for which the Siemreap special region was added to the Northern Zone. This created three additional administrative areas (and one, Siemreap, was omitted):

- the Western Zone (Chou Chet aka Thang Si)

- the Central Zone ( Ke Pauk aka Ke Vin)

- the Kratie special region No. 505

The zones were divided into regions or Damban , which had no names, but only randomly assigned ordinal numbers. The parishes were divided into groups (Krom) of 15 to 20 households under the leadership of a group leader (Meh Krom) . This practice was maintained under the regime of the People's Republic of Kampuchea installed by Vietnam.

economy

The economic policy that the Khmer Rouge implemented in Kampuchea from 1975 is considered a unique revolutionary experiment without a model. It leaned in part on the Great Leap Forward of the People's Republic of China, but went far beyond its radicalism. Cambodian economic policy was shaped by the goal of self-sufficiency and pursued the immediate collectivization of economic life.

After taking power, the Khmer Rouge declared the previous national currency, the Cambodian riel , to be invalid. Initially there were plans to replace it with a new currency - appropriate printing plates were found after the end of the regime - but at the party congress in February 1975 the decision was made to completely abolish the money. From April 1975, trade in Cambodia came to a standstill. In accordance with the principle of self-sufficiency, every community or group was obliged to provide for themselves.

In line with the goal of self-sufficiency, the leadership tried to increase the rice yield in the country by expanding the cultivation areas. In addition, a nationwide system of canals and dams was developed to control the irrigation of the fields. These systems were largely created by hand by the population.

At the same time, foreign trade was almost completely stopped. Only with China was there a regular exchange of goods during the entire rule of the Khmer Rouge.

Autogenocide

A central part of the history of Democratic Kampuchea is the mass murder of its own people. This inwardly directed aggression, known as autogenocide , began in the parts of the country controlled by the Khmer Rouge even before the end of the Lon-Nol regime. After the Khmer Rouge came to power, it continued with increased intensity in all parts of the country. During the evacuation of the cities and the subsequent marches into the rural communities, many Cambodians died of disease and hunger. Later, organized forced labor in the collectivized farms led to numerous deaths. In addition, tens of thousands were executed as "enemies of the revolution", often for no good reason or for the most minor offenses. Party members were not spared from this either. From 1975 to 1978 there were several waves of purges, which also killed high cadres.

Estimates of the total number of victims diverge strongly, Kiernan from the Genocide Studies Program at Yale University gives them more than 1.6 million out of almost 8 million total population. A conservative estimate by Michael Vickery based on population statistics by Angus Maddison is 750,000. Chandler cites the lower limit of 800,000 to 1 million victims, not counting the deaths in the war against Vietnam. Particularly striking publications even speak of two to three million victims.

The clergyman François Ponchaud , who lived in Cambodia until 1975 and then in Thailand , made the genocide in Cambodia known worldwide with his 1977 book Cambodge année zéro . He based his account on his own experiences in Phnom Penh and on eyewitness accounts from Cambodians who had fled to Thailand. One of the few intellectual supporters of the regime in the West was the British university professor Malcolm Caldwell , who was shot in 1978 under still unexplained circumstances immediately after a conversation with Pol Pot in Phnom Penh. Caldwell defended the eviction of the townspeople. It was necessary to “purify and re-educate the urban population through hard work in rice paddies” and saw them as a milder means than the executions that would have occurred without the evacuation.

The tyranny of the Khmer Rouge was dealt with in the British film The Killing Fields in 1984 . The crimes are to be investigated and tried by the Khmer Rouge Tribunal , which was passed by law in 2004 in Cambodia .

See also

Movies

- The long way of hope , feature film by Angelina Jolie based on the autobiographical novel by Loung Ung (United States / Cambodia 2017).

- The Killing Fields , film by Roland Joffé based on a true story (United Kingdom 1984).

literature

- Daniel Bultmann: Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge: The creation of the perfect socialist. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2017, ISBN 978-3-506-78692-0 .

- Daniel Bultmann: Irrigating a Socialist Utopia: Disciplinary Space and Population Control under the Khmer Rouge, 1975–1979. Transcience, Volume 3, Issue 1 (2012), pp. 40-52 ( text link ; PDF; 383 kB).

- Daniel Bultmann: The revolution is eating its children. Lack of legitimation, educational violence and organized terror under the Khmer Rouge. International Asia Forum No. 42, May 2011, ISSN 0020-9449 .

- Ben Kiernan : The Pol Pot Regime. Race, Power and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79. 3. Edition. Yale University Press, New Haven (CT) 2008, ISBN 978-0-300-14434-5 .

- Pivoine Beang, Wynne Cougill: Vanished Stories from Cambodia's New People Under Democratic Kampuchea. Documentation Center of Cambodia, Phnom Penh 2006, ISBN 99950-60-07-8 .

- Karl D. Jackson (Ed.): Cambodia, 1975-1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University, Princeton 1989, ISBN 0-691-07807-6 .

- Craig Etcheson: The Rise and Demise of Democratic Kampuchea. Westview, Boulder 1984, ISBN 0-86531-650-3 .

Web links

- Constitution of Democratic Kampuchea of January 1976. Documentation Center of Cambodia

- Dark Memories of Cambodia's Killing Spree. In: BBC News . January 6, 2009 (BBC contribution commemorating the 30th anniversary of the victory over the Khmer Rouge)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Country directory for official use in the Federal Republic of Germany. Federal Foreign Office , p. 56, as of June 28, 2018 (PDF; 1.3 MB).

- ^ Siegfried Ehrmann: The regime of the Khmer Rouge - a state with many names. In: Spiegel Online , one day . April 9, 2009.

- ^ Cambodia Since April 1975. II. Democratic Kampuchea. Northern Illinois University , Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Interactive Learning Resources for Southeast Asian Languages, Literatures, and Cultures (SEAsite).

- ↑ Khamboly Dy: A History of Democratic Kampuchea (1975–1979). Documentation Center of Cambodia, Phnom Penh 2007, ISBN 99950-60-04-3 .

- ↑ Jeffrey Heyes: Decline of the Khmer Rouge and their Ouster by the Vietnamese. In: Facts and Details. 2008.

- ^ Samuel Totten, Paul Robert Bartrop: Dictionary of Genocide: M – Z. Greenwood Publishing Group, Westport (CT) 2008, ISBN 978-0-313-34644-6 , p. 461.

- ↑ a b Ben Kiernan: The Pol Pot Regime. Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79. Yale University Press, New Haven (CT) 2014, ISBN 978-0-300-14299-0 , p. 437.

- ↑ Philip Short: Pol Pot: The History of a Nightmare , Hachette UK, 2013, ISBN 978-1-4447-8030-7 .

- ↑ Stephen J. Morris: Why Vietnam Invaded Cambodia. Political Culture and Causes of War. Stanford University Press, Chicago 1999, ISBN 978-0-8047-3049-5 , p. 111.

- ^ Russell R. Ross: The Khmer People's National Liberation Front. In: Cambodia. A Country Study. Library of Congress Country Studies , Washington 1987.

- ^ A b John Pilger : The Long Secret Alliance: Uncle Sam and Pol Pot. In: Covert Action Quarterly. Fall 1997.

- ^ Constitution of Democratic Kampuchea from January 1976. Documentation Center of Cambodia.

- ↑ a b c Ben Kiernan: The Pol Pot Regime. Race, Power and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79. Yale University Press, New Haven (CT) 2008, ISBN 978-0-300-14434-5 , p. 326.

- ^ A b Timothy M. Carney : Organization of Power. In: Karl D. Jackson (Ed.): Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1989, ISBN 978-0-691-02541-4 , p. 90.

- ↑ Timothy M. Carney: Organization of Power. In: Karl D. Jackson (Ed.): Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1989, ISBN 978-0-691-02541-4 , p. 92.

- ↑ a b Ben Kiernan: The Pol Pot Regime. Race, Power and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79 , Yale University Press, New Haven (CT) 2008, ISBN 978-0-300-14434-5 , p. 327.

- ↑ Timothy M. Carney: Organization of Power. In: Karl D. Jackson (Ed.): Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1989, ISBN 978-0-691-02541-4 , p. 101.

- ↑ Khieu Ponnery had suffered from paranoid schizophrenia since the early 1970s. As a result of the illness, she has not been able to exercise her offices since at least 1976. In nominal terms, however, she retained her offices. See Philip Short: Pol Pot: The History of a Nightmare. Murray, London 2005, ISBN 978-0-7195-6569-4 , p. 117.

- ↑ Timothy M. Carney: Unexpected Victory. In: Karl D. Jackson (Ed.): Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1989, ISBN 978-0-691-02541-4 , p. 18.

- ↑ Timothy M. Carney: Organization of Power. In: Karl D. Jackson (Ed.): Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1989, ISBN 978-0-691-02541-4 , p. 97.

- ↑ Ben Kiernan: The Pol Pot Regime. Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79. Yale University Press, New Haven (CT) 2014, ISBN 978-0-300-14299-0 , p. 11.

- ^ A b Charles H. Twining: The Economy. In: Karl D. Jackson (Ed.): Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1989, ISBN 978-0-691-02541-4 , p. 111.

- ↑ Pol Pot in a speech on the occasion of the 17th anniversary of the Communist Party of Cambodia, cf. Charles H. Twining: The Economy. In: Karl D. Jackson (Ed.): Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1989, ISBN 978-0-691-02541-4 , p. 110.

- ↑ Andrew Mertha: Brothers in Arms. Chinese Aid To The Khmer Rouge. Cornell University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0-8014-5265-9 , pp. 8 ff.

- ^ David P. Chandler : Brother Number One. A Political Biography of Pol Pot. Revised edition. Silkworm, Chiang Mai 2000, ISBN 978-974-7551-18-1 , pp. 153-155.

- ^ A b James A. Tyner: The Killing of Cambodia: Geopolitics, Genocide, and the Unmaking of Space . Ashgate, Burlington (VT) 2008, ISBN 978-0-7546-7096-4 .

- ↑ Michael Vickery: Cambodia. 1975-1982. South End Press, Boston 1984, ISBN 978-0-89608-189-5 .

- ↑ Timothy M. Carney: Organization of Power. In: Karl D. Jackson (Ed.): Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1989, ISBN 978-0-691-02541-4 , p. 85.

- ^ Charles H. Twining: The Economy. In: Karl D. Jackson (Ed.): Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1989, ISBN 978-0-691-02541-4 , p. 109.

- ^ Charles H. Twining: The Economy. In: Karl D. Jackson (Ed.): Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1989, ISBN 978-0-691-02541-4 , p. 121.

- ↑ a b Dark Memories of Cambodia's Killing Spree. In: BBC News . January 6, 2009.

- ↑ Ben Kiernan : The Pol Pot Regime. Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79. 2nd Edition. Yale University Press, New Haven (CT) 2002, ISBN 978-0-300-09649-1 , p. 458.

- ↑ Steven Rosefielde: Red Holocaust. Routledge, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-203-86437-1 , p. 119 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Malcolm Caldwell : The Cambodian Defense. In: The Guardian . 5th August 1978.