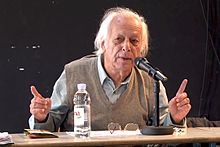

Samir Amin

Samir Amin ( Arabic سمير أمين, DMG Samīr Amīn ; * September 3, 1931 in Cairo ; † August 12, 2018 in Paris ) was an Egyptian - French political economist and critic of neocolonialism . He coined the term “Eurocentrism” as early as 1988 and is considered a pioneer of the dependency theory and an important representative of the world system theory.

Life

Amin was born in 1931 to an Egyptian and a Frenchwoman (both medical doctors). He spent his childhood and youth in Port Said ; There he attended the French grammar school, which he left in 1947 with the Baccalauréat . Amin was already politicized during his school days, when during the Second World War the Egyptian students split up into communists and nationalists - Amin was one of the former. Even then, he took a determined stance against fascism and Nazism. While he was heavily influenced by the Egyptian resistance to British supremacy in Egypt, he still rejected the idea of some Egyptians that the enemy of their enemy (i.e. Nazi Germany) was their friend.

From 1947 to 1957 he studied in Paris , his doctorate in economics (1957) being preceded by a diploma in political science (1952) and statistics (1956). In his autobiography Itinéraire intellectuel (1993), Amin writes that at this time it was important for him to invest a minimum of work in preparing for university exams in order to be able to devote most of the time to “action militante”. For Amin, the intellectual and political struggles remained inextricably linked throughout his life - instead of just explaining the world and its atrocities, he wanted to be part of the struggle for a better world.

When Amin arrived in Paris, he joined the French Communist Party , but later distanced himself from the Soviet system and was close to Maoist circles for a time . Together with other students he published the magazine Étudiants Anticolonialistes.

His political ideas were also strongly influenced by the Conference of the Bandung States in 1955 and the nationalization of the Suez Canal. The latter even caused him to postpone the completion of his dissertation, which he had completed in June 1956.

In 1957 he defended his work, which was supervised by Francois Perroux, among others. It was originally entitled: The Origins of Underdevelopment - Capitalist Accumulation on a World Scale. However, this had to be changed to: The Structural Effects of International Integration of Pre-Capitalist Economies - A theoretical study of the mechanism that gives rise to so-called underdeveloped economies .

After finishing his work, Amin returned to Cairo, where he worked from 1957 to 1960 as research officer for the government's "Institution for Economic Management". There he campaigned for the state to be represented on the supervisory boards of publicly owned companies. With this, Amin entered the very tense political climate associated with the nationalization of the Suez Canal, the war of 1956, the establishment of the non-aligned movement, etc. In particular, his membership in the then secret Communist Party made working conditions difficult.

To avoid personal danger, Amin left Egypt for Paris in 1960, where he worked for the Ministry of Economics and Finance for six months . Amin then left France to become an advisor to the Planning Ministry in Bamako (Mali) under the presidency of Modibo Keata. He held this position from 1960 to 1963 and worked with prominent French economists such as Jean Bénard and Charles Bettelheim. With some skepticism, Amin regards the growing focus on economic growth in order to 'close the gap'. Although he finally gave up working as a bureaucrat after leaving the service in Mali, Samir Amin later acted repeatedly as an advisor for governments in the global South and for African or global institutions. Countries like China, Vietnam, Algeria, Venezuela and Bolivia took advantage of his advice.

In 1963 he became a fellow at the Institut Africain de Développement Économique et de Planification (IDEP) in Dakar . He worked there until 1970 and was also a professor at universities in Poitiers , Dakar and Paris (Paris VIII, Vincennes). In a book in the 1970s he initially supported the Cambodian coup by the “ Khmer Rouge ” because of its “rapid de-urbanization and its economic self-sufficiency” as an alleged model for Africa. He later revised the view and saw the Khmer rule as a mixture of Stalinism and peasant revolt. In 1970 he became director of IDEP, which he headed until 1980. Within this UN organization, Amin created several institutions that eventually became independent entities. Including the predecessor institution of the later Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA), which was designed on the model of the Latin American Council for Social Sciences (CLACSO). In 1980, Amin left IDEP and became director of the Third World Forum in Dakar.

He placed great hopes in the protest movements known as the Arab Spring , but feared from the outset that they would not come true.

"Samir Amin is one of the most important and influential intellectuals in the Third World," said Dieter Senghaas . Amin's theoretical pioneering role was often overlooked because his dissertation from 1957 was only published in an expanded book in 1970 under the title L'accumulation à l'échelle mondiale .

Amin lived in Dakar, Senegal until the end of July 2018 . On July 31, 2018, he was transferred to a hospital in Paris. He died of lung cancer on August 12, 2018 at the age of 86 .

Political theory and strategy

Samir Amin is considered a pioneer of the dependency theory and an important proponent of world systems theory, although he preferred to call himself part of the school of global historical materialism, together with Paul A. Baran and Paul Sweezy (see 2.1). His core idea, which he formulated in his dissertation as early as 1957, was that so-called "underdeveloped" economies should not be viewed as independent units, but as building blocks of a capitalist world economy. In this world economy the 'poor' nations would form the 'periphery', which is forced to permanently adapt structurally to the reproductive dynamics of the 'centers' of the world economy, ie the advanced capitalist industrial countries. At about the same time and with similar basic assumptions, so-called Desarrollismo (CEPAL, Raul Prebisch) emerged in Latin America, which was further developed a decade later in the discussion of “Dependencia” - Wallerstein's “World System Analysis” came up even later. Samir Amin applied Marxism to a global level and used terms such as “world law of value” and “super-exploitation” to analyze the world economy (see 2.1.1). At the same time, his criticism extended to the Marxism of the Soviet Union and its development program of "catching up and overtaking". Amin believed that the countries of the "periphery" could never catch up in the context of the capitalist world economy because of an inherent tendency to polarize the system and because of certain monopolies held by the imperialist countries of the "center" (see 2.1.2). He therefore recommended the 'periphery' to 'decouple' itself from the world economy, i.e. to generate an 'autocentric' development (see 2.2) and to leave the 'Eurocentrism' of modernization theory behind (see 2.3).

Global historical materialism

Based on the analyzes of Karl Marx, Karl Polanyi and Fernand Braudel , the central starting point of Amin's theories is a fundamental critique of capitalism, which focuses on the conflict structure of the world system. Amin notes three fundamental contradictions in capitalist ideology: 1. The requirements of profitability stand against the striving of the working people to determine their own fate (workers' rights and democracy were enforced against capitalist logic); 2. The short-term, rational economic calculation stands against a long-term safeguarding of the future (ecological debate); 3. The expansive dynamics of capitalism lead to polarizing spatial structures - the center-periphery model.

According to Amin, capitalism can be understood as a global system consisting of “developed countries” which form the center and “underdeveloped countries” which form the periphery of the system. Consequently, development and underdevelopment are two sides of the same coin, namely the historical expansion of global capitalism. The poverty of some countries cannot be explained by specific social, cultural or even geographical characteristics. Instead, 'underdevelopment' is the result of the forced permanent structural adjustment of these countries to the needs of accumulation, which benefits the countries at the center of the system. For Amin it came about because the peripheries were treated as outposts, i.e. exclaves of the capitalist centers, and were forced to integrate themselves into the unequal international division of labor, which resulted in a structure of asymmetrical interdependence.

Amin saw himself as part of the school of a 'global historical materialism', less of the other two strands of the dependency theory, the so-called dependencia and the world system theory. The Dependencia School is a Latin American school affiliated with Ruy Mauro Marini, Theoténio dos Santos and Raél Prebisch. Important representatives of the world system theory are Immanuel Wallerstein and Giovanni Arrighi. While these use largely similar scientific vocabulary, Amin declined e.g. B. the concept of the semi-periphery. Amin was also against theorising capitalism as cyclical (as in Nikolai Kondratjew ) or any kind of historical back-projection, thus advocating a minority position within world systems theorists .

For Amin, global historical materialism initially meant the application of Marxism to the world economy. He assigned researchers like Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy to the same approach. The focus of this was the Marxist law of value. Still, Amin insisted that the economic laws of capitalism, summarized by the law of value, are subordinate to the laws of historical materialism. According to Amin's understanding of these terms, this means that economics, albeit indispensable, cannot fully explain reality, largely because it cannot systematically take into account the historical origins of the system itself or the results of class struggles.

“History is not governed by the infallible unfolding of the 'laws of pure economy'. It is generated by the social reactions to the tendencies which are expressed in these laws and which in turn determine the social conditions within which these laws function. The 'anti-systemic' forces ... have a shaping effect on real history just like the 'pure' logic of capitalist accumulation. " (Samir Amin)

Worldwide law of value

Amin's theory of a world law of value describes a system of unequal exchange in which the difference in wages between workers in different nations is greater than the difference between their productivities. Amin speaks of "imperial rents" that would flow to the global corporations in the center - it can also be understood as a kind of global arbitrage .

Historically, an important feature of the economic rise of states in Europe and the USA was a broad-based agricultural revolution and industrialization, with a corresponding increase in real wages, which followed the increase in productivity through social development. This has led to internal market dynamics and the production of goods for a mass market. This relationship between productivity and real wage development is found in developing countries , e.g. B. on the African continent, does not take place. In Amin's view, the cause of this bad situation is the export economy in developing countries with an exclusive structure .

That remained with this inequality lies u. a. that while free trade and relatively open borders allowed multinational corporations to move to where the cheapest work could be found, governments continued to promote the interests of "their" corporations over those of other countries and to limit human mobility. Accordingly, the periphery is still not really connected to the global labor markets, accumulation there has stagnated and wages have remained low. In contrast, accumulation in the centers was cumulative and wages rose in line with increasing productivity.

This situation is maintained by the existence of a massive global reserve army, mainly in the periphery, while these countries are at the same time more structurally dependent and their governments tend to suppress social movements that could win higher wages. Amin calls this global dynamic "development of underdevelopment". The above-mentioned existence of a lower rate of labor exploitation in the north and a higher 'super-exploitation' rate of labor in the south is also seen as one of the main obstacles to the unity of the international working class. In addition, the core countries would hold monopolies on technology, the control of financial flows, military power, ideological production and access to natural resources (see also 2.1.2).

Imperialism and Monopoly Capitalism

According to Amin, the “global law of value” explained above also means that there is in toto an imperial world system which includes the global north and the global south. Amin also believed that capitalism and imperialism were linked at all stages of their development (in contrast to Lenin, who argued that imperialism was a specific phase in the development of capitalism). Amin defined imperialism as “the necessary amalgamation of requirements and laws for the reproduction of capital; the underlying social, national and international alliances; and the policies of these alliances ”.

According to Amin, capitalism and imperialism have shaped everything from the European conquest of America in the sixteenth century to the present phase, which he termed "monopoly capitalism". In addition, the polarization between center and periphery is a phenomenon that is always inherent in this system.

Referring to Arrighi, Amin distinguished the following polarization mechanisms: 1. capital flight from the periphery to the center; 2. selective migration of workers in the same direction; 3. The monopoly of the central societies in the global division of labor, especially the technology monopoly and the monopoly of global finances; 4. Control of the centers over access to natural resources. The forms of polarization between the center and the periphery, as well as the forms of expression of imperialism would have changed in the course of time - but only in the direction of a sharpening of the polarization and not a softening.

Historically, Amin distinguishes three phases: mercantilism (1500–1800), expansion (1800–1880) and monopoly capitalism (1880-present). Amin added that the current phase is dominated by generalized, financialized and globalized oligopolies, which are mainly owned by the triad US, Europe and Japan. They practiced a kind of collective imperialism with military, economic and financial instruments such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Trade Organization (WTO). The triad enjoyed monopoly in five areas: weapons of mass destruction; Mass communication systems; Monetary and financial systems; Technologies; Access to natural resources. They would want to prevent the loss of these monopolies at all costs, also militarily.

Amin further distinguished two phases in the development of monopoly capitalism: the actual monopoly capitalism until 1971 and then the oligopoly finance capitalism. He viewed the financialization and “deepened globalization” of the latter as a strategic response to economic stagnation. He saw stagnation as the rule, while rapid economic growth was the exception in late capitalism. According to him, the rapid growth from 1945 to 1975 was mainly the result of historical conditions attributable to World War II and which could not last. The focus on financialization, which emerged in the late 1970s after the phase of Keynesian global control , was for him "inseparable from the survival requirements of the system", even though it ultimately led to the financial crisis of 2007-2008.

According to Amin, the political systems in the south are often distorted towards autocratic rule as a result of imperialism and 'super-exploitation'. In order to maintain control of the periphery, the imperial powers encouraged backward-looking social relationships based on archaic elements. Amin argued, for example, that political Islam is primarily a result of imperialism. The introduction of democracy in the Global South, without changing the basic social relations or calling imperialism into question, is nothing more than a “fraud” in two respects, if one also considers the plutocratic character of the so-called successful democracies in the North consider.

Delinking (decoupling)

Amin was certain that the emancipation of the so-called "underdeveloped" countries was not possible within the globalized capitalist system. The global south could never catch up in such a capitalist context because of the system-inherent polarization tendency. Therefore, the project that the Asian-African countries decided upon at the Bandung Conference (Indonesia) in 1955 was of great importance to Samir Amin.

Amin advised peripheral countries to decouple themselves from the world economy in order to subordinate global relations to national development priorities and to achieve “autocentric” development (but not self-sufficiency). Instead of having values determined by world market prices - which result from productivity in the rich countries - Amin suggested that each country determine values individually, for example by the workers in agriculture and industry paying through their contribution to the net production of society become. In this way, a national law of value would be defined without reference to the global law of value of the capitalist system (for example, food sovereignty instead of free trade or minimum wages instead of international competitiveness would be decisive). The main effect of this move should be an increase in agricultural wages. Amin also suggested that nation states redistribute resources between sectors and centralize and distribute added value. Full employment should be guaranteed by the state and incentives should be offered to prevent emigration from rural to urban areas.

After decolonization at the state level, this should lead to an economic liberation from neocolonialism. However, Amin stressed that it was almost impossible to 'disconnect' 100%, and already considered a disengagement of 70% to be a significant achievement. Relatively stable countries with some military power would have an easier time in this regard than small countries. For example, China's development is 50% determined by its sovereign project and 50% by globalization. When asked about Brazil and India, Amin estimated that 20% of them were driven by sovereign projects and 80% by globalization; South Africa was even 100% determined by globalization.

In addition, it was clear to Amin that such a decoupling would also require certain political prerequisites within a country. His country studies, initially limited to North and Black Africa, taught him that an appropriate elite, above all a national bourgeoisie oriented towards a national project, did not exist and was also not emerging. Rather, he observed everywhere the development of a 'comprador bourgeoisie' who would benefit from the integration of their respective countries into the asymmetrically structured capitalist world market. For the project of the auto-centered new beginning (the decoupling) he instead hoped for social movements, which is why he was involved in numerous non-governmental organizations until the end.

Eurocentrism

Amin proposed an interpretation of the history of civilization according to which certain coincidences first led to the development of capitalism in the societies of the West. This then led to a division of the world in two because of the aggressive expansion character of (colonialist) capitalism. Amin therefore argued that it was a mistake to view Europe as the center of civilization of the world simply because it was dominant in the early capitalist period.

For Amin, Eurocentrism was not just a worldview, but a global project that aims to homogenize the world based on the European model under the pretext of “catching up”. In practice, however, capitalism does not homogenize the world, but polarizes it (see 2.1.2). Eurocentrism is therefore more an ideal than a real possibility. But it reinforces racism and imperialism and there is a permanent risk of fascism, since it is ultimately an extreme version of Eurocentrism.

Fonts

German language fonts

- The uneven development. Essay on the social formations of peripheral capitalism. 1975.

- The realm of chaos. The new advance of the first world . VSA, Hamburg 1992.

- The future of the world system. Challenges of globalization. VSA, Hamburg 2002.

- For a non-American 21st century. VSA, 2003, ISBN 3-89965-022-0

- Apartheid global. The new imperialism and the global south. In: Blätter für German and international politics (Ed.): The sound of factual constraint - The globalization reader. Pages 11–17. With 30 contributions by Elmar Altvater , Samir Amin, Peter Bender , Noam Chomsky, Mike Davis, Erhard Eppler , Johan Galtung, Jürgen Habermas , Samuel P. Huntington, Naomi Klein , Birgit Mahnkopf , Peter Marcuse , Saskia Sassen u. v. a. Blätter Verlagsgesellschaft, 4th edition 2006, ISBN 978-3-9804925-3-9 .

- The globalized law of value. Laika Verlag, Hamburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-942281-21-8 .

- Sovereignty in the service of the people. Plea for anti-capitalist national development. (with an introduction by Andrea Komlosy ), Promedia Verlag, Vienna 2018, ISBN 978-3-85371-453-9 .

French language fonts

Amin's books first appeared in French. Many have been translated into English.

- (1957): Les effets structurels de l'intégration internationale des économies précapitalistes. Une étude théorique du mécanisme qui a engendré les éonomies dites sous-développées (dissertation)

- (1964): L'Egypte Nassérienne

- (1965): Trois expériences africaines de développement: le Mali, la Guinée et le Ghana

- (1966): L'économie du Maghreb, 2 vols.

- (1967): Le développement du capitalisme en Côte d'Ivoire

- (1969): Le monde des affaires sénégalais

- (1969): The Class struggle in Africa

- (1970): Le Maghreb moderne (translation: The Maghreb in the Modern World)

- (1970): L'accumulation à l'échelle mondiale, engl. Accumulation on a World Scale: Critique of the Theory of Underdevelopment, 1978

- (1970, with C. Coquery-Vidrovitch): Histoire économique du Congo 1880–1968

- (1971): L'Afrique de l'Ouest bloquée

- (1973): Le développement inégal (translation: Unequal development)

- (1973): L'échange inégal et la loi de la valeur

- (1973) Neocolonialism in West Africa

- (1974, with K. Vergopoulos): La question paysanne et le capitalisme

- (1975, with A. Faire, M. Hussein and G. Massiah): La crise de l'impérialisme

- (1976): L'impérialisme et le développement inégal, engl. Imperialism and unequal development

- (1976): La nation arabe engl. Arab Nation: Nationalism and Class Struggles, Zed press 1978

- (1977): La loi de la valeur et le matérialisme historique (translation: The law of value and historical materialism)

- (1979): Classe et nation dans l'histoire et la crise contemporaine (translation: Class and nation, historically and in the current crisis)

- (1980): L'économie arabe contemporaine (translation: The Arab economy today)

- (1981): L'avenir du Maoïsme (translation: The Future of Maoism)

- (1982, with G. Arrighi , AG Frank and I. Wallerstein): La crise, quelle crise? (translation: Crisis, what crisis?)

- (1982): Irak et Syrie 1960–1980

- (1983): The Future of Maoism , Monthly Review Press

- (1984): Transforming the world-economy? : nine critical essays on the new international economic order.

- (1985): La déconnexion, engl. Delinking: towards a polycentric world

- (1988): L'eurocentrisme, engl. Eurocentrism , Monthly Review Press 1989

- (1988, with F. Yachir): La Méditerranée dans le système mondial

- (1988): Impérialisme et sous-développement en Afrique (extended new edition)

- (1989): La faillite du développement en Afrique et dans le tiers monde: une analyze politique, Paris: Éd. l'Harmattan

- (1990) Transforming the revolution: social movements and the world system

- (1990): Itineraire intellectual; regards sur le demi-siecle 1945–1990, engl. Re-reading the post-war period: an Intellectual Itinerary

- (1991, with G. Arrighi, AG Frank and Immanuel Wallerstein ): Le grand tumulte

- (1991): L'Empire du chaos engl. Empire of chaos

- (1991): Les enjeux stratégiques en Méditerranée

- (1994): L'Ethnie à l'assaut des nations

- (1995): La gestion capitaliste de la crise

- (1996): Les défis de la mondialisation, engl. Capitalism in the Age of Globalization: The Management of Contemporary Society, Zed Books 1997

- (1997): Critique de l'air du temps, engl. Specters of Capitalism: A Critique of Current Intellectual Fashions , Monthly Review Press 1998

- (2000): L'hégémonisme des États-Unis et l'effacement du projet européen

- (2002): Mondialisation, comprehendre pour agir

- (2003): Obsolescent Capitalism

- (2004): The Liberal Virus: Permanent War and the Americanization of the World, Monthly Review Press 2004

- (2004) Obsolescent capitalism. Contemporary Politics and Global Disorder, Zed Books

- (2005 with Ali El Kenz) Europe and the Arab world; patterns and prospects for the new relationship

- (2006) Beyond US Hegemony: Assessing the Prospects for a Multipolar World

Secondary literature

- Aidan Forster-Carter: The Empirical Samir Amin. In S. Amin: The Arab Economy Today. London 1982, pp. 1-40

- Duru Tobi: On Amin's Concepts - autocentric / blocked development in Historical Perspectives. In: Economic Papers. (Warsaw), No. 15, 1987, pp. 143-163.

- Fouad Nohra: Théories du capitalisme mondial. Paris 1997.

- Gerald M. Meier, Dudley Seers (Eds.): Pioneers in Development. Oxford 1984.

- Joachim Wilke: Samir Amin's project on a long road to global socialism. Diversity of Socialist Thought Issue 13. Ed. Helle Panke Berlin.

- Kufakurinani, U .: Styve, MD; Kvangraven, IH (2019): Samir Amin and beyond , available at: https://africasacountry.com/2019/03/samir-amin-and-beyond [accessed June 05, 2019]

Individual evidence

- ↑ Left economist Samir Amin dies: Farewell to a Marxist , taz.de, August 14, 2018

- ^ "A Brief Biography of Samir Amin" - Monthly Review, Vol. 44, Issue 4, September 1992 | Online Research Library: Questia. Retrieved April 27, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c d e Alfred Germ: Samir Amin's approach to the world system . In: Joachim WIlke (Hrsg.): The future of the world system: Challenges of globalization . VSA-Verlag, Hamburg 1997, p. 1, 2 .

- ↑ a b c d e f I. H. Kvangraven: A Dependency Pioneer: Samir Amin . 2017, p. 12 ( https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317603001_A_Dependency_Pioneer_-_Samir_Amin [Accessed June 5, 2019]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Günter Hans Brauch: Springer Briefs on Pioneers in Science and Practice: Volume 16: Samir Amin Pioneer of the Rise of the South . Springer Verlag, 2014, p. vi, xiii, 5, 8, 9, 143 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i D. Senghaas: Zeitdiagnostik, inspired by creative utopia: Laudation to Samir Amin on the occasion of the award of the Ibn Rushd Prize for Free Thinking on December 4th, 2009 in Berlin . 2009 ( https://www.ibn-rushd.org/typo3/cms/de/awards/2009-samir-amin/laudatory-held-prof-dieter-senghaas/ [Accessed 4 Jun. 2019]).

- ↑ Presentation générale de l'IDEP ( Memento of November 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ in: Imperialism and Unequal Development. Harvester Press, Brighton 1977, p. 177, cf. Arnaldo Pellini: Decentralization Policy in Cambodia. Diss. 2007, Uni Tampere, p. 62 ( PDF ).

- ↑ cf. on this George J. Andreopoulos (Ed.): Genocide: conceptual and historical dimensions. University of Pennsylvania Press 1994, p. 202.

- ↑ D + C - Development and Cooperation (No. 6, June 2001, pp. 196-199): Samir Amin (* 1931). Accumulation at the World Level - Auto-Centered Development. Dieter Senghaas ( Memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ WIDERSPRUCH 60/11, pp. 12–16: Samir Amin, Arab Spring?

- ↑ Egyptian-French economist Samir Amin dies , apanews.net, August 13, 2018

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i John Bellamy FosterTopics: Economic Theory, History, Imperialism, Political Economy, Stagnation: Monthly Review | Samir Amin at 80: An Introduction and Tribute. In: Monthly Review. October 1, 2011, accessed April 27, 2020 (American English).

- ↑ a b To AZ of theory Samir Amin (Part 1) | Ceasefire Magazine. Retrieved April 27, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c To AZ of theory Samir Amin (Part 2) | Ceasefire Magazine. Retrieved April 27, 2020 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Samir Amin in the catalog of the German National Library

- Entry on Samir Amin in the virtual personal lexicon of international relations (PIBv), edited by Ulrich Menzel , Institute for Social Sciences at the Technical University of Braunschweig .

Article by Samir Amir online

- The American Ideology

- Third World Forum: An Interview with Samir Amin ( Memento from August 22, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- Imperialism and Globalization ( Memento of January 3, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- Empire of Chaos Challenged: An Interview with Samir Amin

- Maldevelopment: Anatomy of a Global Failure ( Memento of September 30, 2000 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- US Imperialism, Europe, and the Middle East

- India, a Great Power?

- Imperialism and Globalization

- World Poverty, Pauperization & Capital Accumulation

- US Hegemony and the Response to Terror

- Empire and Multitude

- A Note on the Death of André Gunder Frank (1929-2005)

- The Political Economy of the Twentieth Century

- Africa: Living on the Fringe

Texts about Amin Samin

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Amin, Samir |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Egyptian-French economist and critic of neocolonialism |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 3, 1931 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Cairo |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 12, 2018 |

| Place of death | Paris |