Katharinenhospital Esslingen

| Catherine Hospital | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Data | |

| place | Esslingen am Neckar |

| Construction year | before 1232 |

| demolition | from 1815 |

| Floor space | at least 5500 m² |

The St. Catherine's Hospital in Esslingen am Neckar is one of the holy Katharina consecrated Hospital , which was first mentioned in the 1232nd Both men and women formed a lay brotherhood, which lived as a religious community from 1247 according to the Augustine rules.

At the end of the 13th century the hospital was moved to what is now Esslingen's market square. From 1815, the tasks of the Katharinen Hospital were taken over by today's Obertor nursing home, at that time still St. Clarisse's Monastery, and the hospital building was demolished. The former location has not yet been archaeologically examined.

history

middle Ages

The oldest surviving mention of the Katharinen Hospital comes from 1232 and is in one of Pope Gregory IX. Certificate of Confirmation issued confirming Master and Brotherhood protection and the pre-existing and future ownership of the facility. The purpose of the hospital was to receive and care for pilgrims , women giving birth, foundlings , the weak, the lame and other needy people free of charge. The hospital's increasing bourgeoisisation was already completed in 1335, which meant that almost exclusively locals were admitted. Today's research assesses this process, among other things, as a process of "gradual differentiation and expansion of the welfare system". The hospital was supplemented in 1268 with an infirmary - it was located in what is now Ritterstraße - which was placed on the eastern outskirts for lepers and expanded by two buildings in the 13th century. An orphanage was established in the 1440s . In 1411 a lake house was added, which was responsible for the supply of travelers. At the end of the 15th century, a "leaf house" for those suffering from syphilis and a facility that looked after the custody of the aggressive mentally ill and was known as the "fool's house" were built. Presumably, however, there was no strict separation between locals and foreigners. The institutions did not all have the same legal status, but were perceived as coherent due to the interweaving of funding and staff. While the Katharinenhospital was initially a free facility, beneficiaries bought admission over time. This included both young and old people who, for example, needed care because of physical or mental disabilities or mental illness, but also widows and unmarried women outside of a family group. There is no reliable evidence of epidemics that raged in Esslingen before the early 15th century. Presumably, however, the plague broke out in the 14th century, which the inscription above the lintel of the central nave south portal of St. Dionysius, on which the word “pestis” is written. In the 15th century (possibly 1419) the plague of Nicholas of the Sword was written, which refers to an epidemic in Esslingen and reports on prophylactic measures against the plague. However, the exact dating of these epidemics is not possible. Furthermore, epidemic refugees from 1438 and epidemics in the surrounding area from 1450 are known, which may have influenced Esslingen and thus the facilities of the Katharinen Hospital. It was not until 1472 that there was first reliable evidence of an epidemic in Esslingen.

Early modern age

Between the 13th and 16th centuries, the hospital administration bought both buildings and land to the hospital's assets in order to create more living space for beneficiaries as well as space for chapels and commercial outposts. In the 17th century, the Poor Clare Monastery, which had another poor house with a hospital function, took over the tasks of the Katharinen Hospital together with the Preacher's Monastery, which had the function of a work center for the poor, orphans and prisoners. The latter had a huge financial deficit over time and only poorly maintained its building fabric. It had noticeably lost its importance and was finally judged at the beginning of the 19th century to be “unattractive and completely unsuitable”.

care

species

Beneficiary contracts could largely be individualized, both in terms of price and services that the hospital had to provide for the beneficiary. It should be noted that not all services can be taken from the contracts, as some services were obviously taken for granted and not listed. Four types of benefice existed in the Katharinenhospital:

- The Poor Pfründe or Siechenpfründe was the cheapest form of contract with around 23-25 guilders (florins) in the 15th century. The beneficiaries lived with the needy in the poor rooms, had to follow the house rules and received the same food. Only a small part of the population could afford this type of benefice, but in the 15th century it was still 20-30% of taxes paying population. Benefices, however, were the only alternative for those who had no families.

- The Herrenpfründe and Mittelpfründe were combined, the beneficiaries were called "brothers" and "sisters". According to their respective beneficiary contract, they received better food and lived either in the brothers' room, in their own rooms, which were either lived in alone or with a spouse, or with a few other brothers or sisters. The minimum price of such a benefice was around 100 guilders in the 15th century, which around a third of the tax-paying population could afford. In view of the income in the 15th century and horrific food prices, such a benefice could almost exclusively be afforded by people who had the income of a master in the building trade or who came from such a family.

- The oath of obedience was intended for those who were able to work and who undertook to provide the hospital with services such. B. to work as maidservants as long as they were able to work or for a few years. They received board, lodging, clothing and money. If they were unable to work, they could acquire a brother (male or middle) or an infirmary for themselves. An oath of obedience for a couple cost 46 guilders per spouse in the 15th century. It should be noted, however, that married couples acquired individual benefices, but received benefits due to the marriage.

- The store credit was the main source of income for the hospital. People who were shop-founders picked up food from the hospital's kitchen shop every day. They did not live in the hospital buildings and were not bound by hospital regulations.

Prices

The prices of benefices were not absolutely fixed. A "basic price" seems to have existed, but it was changed after the following circumstances:

- agreed scope of services,

- Beneficiary health,

- its expected service life,

- Type of payment (cash or in installments, in gulden or lighter, transfer of property or money claims or through different combinations of these options),

- Supply and demand from and to benefices and

- partly also according to the current cost of food.

In the 16th century, benefices became more expensive:

| designation | 15th century (in guilders) | 16th century (in guilders) | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brothers and Sisters Loans | 100-150 | 200 | End of the 16th century: 600–700 guilders |

| Oaths of obedience | 46 | 100 | |

| Poor pledges | 25th | 80-90 |

Residents

General Information

Overall, there were more women than men in the Katharinenhospital. Of the 5,000–6,000 inhabitants that Esslingen had in the 15th century, around 5–6% were cared for by the hospital, as the hospital fed at least 300 people a day. A visitation report from 1532 contains information on the quantities of bread that came to different places. The hospital's kitchen shop received 135 loaves of bread per day, the brothers' parlor 15. This resulted in 135 shop beneficiaries, which once again shows the popularity of this type of beneficiary, and 15 brother and sister beneficiaries. Furthermore, 45 poor people and 28 poor beneficiaries or sick people are assumed. Of a further 70 people, it can be assumed that they were not housed in the hospital, but in other poor houses, in the Seelhaus or in the "warts house".

The social origin of the beneficiaries is often not evident from the contracts. From Esslingen, however, some former guild masters , sacristans, the sister of a wealthy clergyman, a sub-builder, the wife of a gravedigger and a brothel keeper are known, which shows the overall social heterogeneity of the benefactors.

Women made up the majority of hospital residents. This was by no means unusual, as women were generally more at risk of poverty than men. This was due to the fewer and limited employment opportunities available to women.

The poor

The Katharinenhospital looked after the needy as well as benefiting. There is evidence that the poor were provided in part with payments from beneficiaries who bought into care.

The conditions in which the poor lived were cramped. From the visitation report, which also recorded the amount of bread, it emerges that those who are lying in the poor room and will soon die have no peace at all, it is like "in the junk house", by which the department store is meant. Nor does it seem that there was a bed for every poor person during the visitation. A hospital regulation from 1533 emphasizes that everyone has their own bed. It was cramped in the poor rooms, as up to 80 people were accommodated in these rooms, who almost never left these rooms. Another problem in the poor rooms was probably the theft of food, the amount of which there was small compared to the much more generous provision for brothers and sisters. Caring for the poor was lacking in both quantity and quality. On feast days they were often only given fish (instead of meat).

brothers and sisters

At least some of the brothers and sisters had quarters in houses on the northern city wall and on the western side of the area. These were probably not only bigger but also lighter than the poor houses. Their benefices were characterized by better lodging and better food. On feast days they were given roasts or poultry. The brothers and sisters received more and, above all, better wine and better bread. Overall, their diet was richer and more varied than that of the poor and sick. In contrast to the diet of the poor and the sick, meat was the rule in the diet of the brothers and sisters, and cheese and eggs were not uncommon on fasting days alongside fish.

The following case is mentioned as an example: Hans von Urbach was a benefactor of the hospital. In 1472 he bought a brother or man's mortgage, which cost him 160 Rheinische Gulden (rh. Fl.) And brought him the services mentioned above. In his beneficiary agreement, in addition to the normal friars' food and accommodation, wine in the fall and a cellar were also included. Little by little, Hans von Urbach bequeathed further assets to the hospital and probably made the Katharinenhospital his heir in 1501. He lived in the hospital for a total of 30 years, so it can be assumed that he suffered from a chronic illness that did not lead to immediate death. Such a long stay in the hospital was rather rare, but not that the hospital was used as an inheritance. There were also far more expensive benefices: Englin Grasmann von Vaihingen paid the amount of 231 Rhenish guilders for a sister benefice in 1434.

Building and location

The Katharinenhospital was centrally located on today's market square. The Katharinenhospital between the parish church of St. Dionys and the Dominican monastery , the Schwörhof and the market square is registered on the Kandlerschen Riss , a local view . Shortly before the hospital was demolished, the surveyor Johann Gottlieb Mayer prepared the floor plan of the building complex. The hospital had a floor area of about 55 acres, but was not designed so large from the start. Between the 13th and 16th centuries, the hospital administration gradually acquired the area that is recorded on the Kandler crack from 1774 and on the floor plan from 1810.

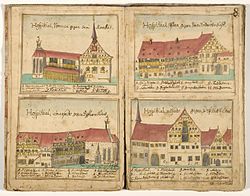

The drawings by Tobias Mayer, who was only 14 years old at the time of creation, provide the greatest and most vivid information about the structure of the main building complex. He made a view from all directions. A detailed drawing of the inner courtyard is missing, however, so that its structure is mainly based on speculation. However, there seem to have been bread boxes in the inner courtyard for feeding the poor, which supplied around 300 people with bread every day. The construction of the new hospital chapel is recorded on a crack by Hans Böblinger, son of the builder of the chapel, in 1501. It is assumed, however, that this crack was made on the basis of construction plans and that the chapel was ultimately made simpler due to the high costs.

After the hospital was closed, the buildings were gradually sold for demolition from 1811 to 1817. Although the art historian Carl Alexander Heideloff had campaigned for the preservation of the hospital chapel because of its artistic importance, it was also demolished. The residents of the facility, of whom only seven were beneficiaries, moved either to the Poor Clare Monastery or the Preacher Monastery. Beneficence was finally abolished completely due to the lack of demand.

Today only the wine press in the Kielmeyerhaus is structurally preserved from the Katharinenhospital . The oversized marketplace is still reminiscent of the furnishings. A single altar wing from the furnishings of the hospital chapel in the church of Deizisau is also preserved, which is said to have been taken away by a carpenter. This altar wing dates from the last decade of the 15th century and was attributed to the Esslingen painter Matthias Ulin-Wolf the Younger († 1536) by the art historian Hans Rott . The inside of the altar wing shows the Saints Agnes and Christophorus , on the outside the motif of the sending out of the apostles .

Institutions related to the hospital

| building | Establishment | function | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infirmary | 1268 | Accommodation for lepers | Eastern outskirts |

| two more infirmaries | in the 13th century | Accommodation for lepers, replaced the infirmary in 1268 | Landmarks of the neighboring towns of Mettingen (Esslingen am Neckar) and Oberesslingen |

| Orphanage | before 1344 | Accommodation for orphans up to the age of majority | |

| Seelhaus | 1411 | Caring for foreign travelers | |

| Leaf house | Late 15th century | Accommodation of syphilitics | |

| "Narrenhäusle" | Late 15th century | Repository for the aggressive insane |

Construction work on the main building

| Part of the building | Establishment | function | place |

|---|---|---|---|

| main building | .. | Accommodation and common room for beneficiaries and employees, economic establishment | Between the parish church of St. Dionys, Dominican monastery with Schörhof and market square |

| Hospital chapel | 1247 | North side | |

| Cemetery chapel | 1316 | Funeral chapel (dedicated to St. Agnes) | |

| Beneficiary accommodation | Acquired in 1310 from the Weiler monastery | Housing of beneficiaries | Houses and land on the city wall |

| Wine press | 1582 | Wine press, accommodation for the hospital forest manager, storage rooms | Market square, today Kielmeyerhaus |

| Residential tower | Purchase in 1379 and 1420 in two halves, demolished in the 15th century | Development of the area with a new hospital chapel and building with a poor house | South side |

| Renewal of the hospital chapel (1247) | Planned in 1482, fire on the east side in 1484, relocation of the construction project | First northeast corner, after fire southeast corner | |

| House and other buildings | 1422 | Accommodation of beneficiaries | West side |

| Superstructure house and building from 1422 ("new building") | 1589 | Beneficiary dwellings | West side |

Construction of the main building

| Spatiality | function | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Chapel with choir | Market side | |

| Facade with clock and bell tower | Clock made in 1502, with imperial head and imperial hand, which moved every hour - representative function of the administration | Market side |

| Portal depicting St. Catherine and heraldic shield | Market side | |

| Hospital room | Accommodation of the sick | Market side, first floor |

| Poor houses | Accommodation of poor benefactors | Market side, first floor, connected to the hospital room |

| Wheeling | Market side, ground floor | |

| Market stalls (probably fell away by the 19th century) | Sale of goods | Market side, ground floor |

| Hospital hall (2) and "Hospital-Saal-Kammer" | Accommodation of the sick, hall presumably as a lounge and chamber as a dormitory | North side, first floor, middle of the complex |

| new building from 1589 | 8–10 beneficiary apartments | North side and west side |

| Utility rooms (hospital cooperage, butchery, crockery room) | North side, ground floor | |

| Wood and hay house | Storage rooms for beneficiaries | North side |

| Grain soils | Storage rooms | North side, above the hospital hall and beneficiary apartments |

| Registrar | North side, ground floor | |

| Cooperage and horse stable | West side, at ground level | |

| Wood stocks of the beneficiaries | Depository | West side, at ground level |

| Fountain | Water supply | patio |

| Bread boxes | Distribution of bread to shop owners and the poor | patio |

| Poor chambers | Accommodation of poor benefactors | West side, first floor |

| Spring stages | West side, first floor | |

| Poor houses | Common rooms for poor benefactors | South side, ground floor |

| Death chamber | South side, next to the poor houses | |

| Hospital cemetery | South side | |

| Poor chamber | Separate dormitory for the poor benefactors, meanwhile furnished | South side, above the death chamber |

| Condominium apartments and the hospital clerk's apartment | Residential section | South side, over poor quarters |

| Hospital father's apartment | Living room | South side |

| Attics (granary and "main room") | Storage of grain and leather or manufacture of leather |

literature

- Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: The building of the Katharinen Hospital in the former imperial city of Esslingen am Neckar . In: Southwest German contributions to historical building research . tape 8 , 2009, p. 31-40 .

- Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: Benefactors and needy people in the Katharinenhospital in Esslingen: social stratification, care and everyday life in the 15th and 16th centuries . In: Esslinger Studies. Magazine. tape 44 , 2005, pp. 7-35 .

- Friedrich R. Wollmershäuser: The staff of Esslingen Hospital in 1595 . In: Südwestdeutsche Blätter for family history and heraldry . tape 23 , 2003, p. 167-170 .

- Bernhard Roll: From hospital to foundation: the Esslingen Sankt Katharinenhospital between midatisation and peasant liberation 1803-1830 . In: Esslinger Studies. Magazine . tape 34 , 1995, pp. 47-112 .

- Reinhard Mauz: Denkendorf residents in the distribution books of the Esslingen St. Katharinen Hospital: Accompanying material to the Denkendorf Family Register . Denkendorf 2013.

- Württembergisches Urkundenbuch (WUB) 11 vol. Stuttgart 1849–1913, ND Aalen 1972–78.

- Patrick Sturm: Life with death in the imperial cities of Esslingen, Nördlingen and Schwäbisch Hall - epidemics and their effects from the early 15th to the early 17th century . In: Esslinger Studies . tape 23 , 2014.

Web links

- Homepage of the Esslingen Clinic, about the history

- Regional information system for Baden-Württemberg for the Katharinen Hospital

- Esslinger picture book: market square

Individual evidence

- ↑ WUB 3, No. 814.

- ↑ Quoted from Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: The buildings of the Katharinen Hospital in the former imperial city of Esslingen am Neckar. In: Southwest German contributions to historical building research. -8 pp. 31-40, Stuttgart 2005.

- ↑ WUB 6, No. 1987

- ^ Haug: Katharinenhospital , p. 141 f.

- ↑ EUB 2, No. 1919, September 28, 1411

- ^ Haug: Katharinenhospital , p. 145 f.

- ↑ Patrick Sturm: Living with death in the imperial cities of Esslingen, Nördlingen and Schwäbisch Hall epidemics and their effects from the early 15th to the early 17th century, in: Esslinger Studien Volume 23, 2014, p. 34

- ↑ Patrick Sturm: Living with Death in the Imperial Cities of Esslingen, Nördlingen and Schwäbisch Hall - Epidemics and their Effects from the Early 15th to the Early 17th Century, in: Esslinger Studien Volume 23, 2014, p. 34

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: The building of the Katharinenhospital in the former imperial city Esslingen am Neckar .

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: Beneficiaries and needy , p. 15.

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: Beneficiaries and needy , p. 16.

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: The building of the Katharinenhospital in the former imperial city Esslingen am Neckar. In: Southwest German contributions to historical building research. 8. Stuttgart 2009, p. 33.

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: Benefactors and needy. P. 15 f., P. 19.

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: Beneficiaries and needy , p. 15.

- ↑ Information from Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: beneficiaries and needy , p. 15.

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: Benefactors and needy , p. 20.

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: Benefactors and needy people in the Katharinenhospital in Esslingen. Social stratification, care and everyday life in the 15th and 16th centuries , p. 11.

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: The building of the Katharinenhospital in the former imperial city Esslingen am Neckar . In: Southwest German contributions to historical building research. 8. Stuttgart 2009, p. 33.

- ↑ Robert Uhland, Hans von Urbach: Beneficiary in the hospital in Esslingen. In: Esslinger Studien 1 (1956), pp. 29-35.

- ↑ Can be viewed in the Esslingen City Archives .

- ^ Floor plan of the Esslingen hospital by Johann Gottlieb Mayer, 1810. Present in the drawing by Benz from 1896. Can be viewed in the Esslingen City Archives.

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: The Buildings , p. 34.

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: Beneficiaries and needy , p. 19.

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: The Buildings , p. 34.

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: The building of the Katharinenhospital in the former imperial city Esslingen am Neckar .

- ↑ Hans Rott: Sources and research on southwest German and Swiss art history in the 15th and 16th centuries 2: Old Swabia and the imperial cities. Stuttgart 1934, p. 60.

- ↑ Gustav Ebe: The German Cicerone: Guide through the art treasures of the countries of the German tongue 3: Painting. Leipzig 1898, p. 95.

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: The building of the Katharinenhospital in the former imperial city Esslingen am Neckar

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: The building of the Katharinenhospital in the former imperial city Esslingen am Neckar

- ↑ Iris Holzwart-Schäfer: The building of the Katharinenhospital in the former imperial city Esslingen am Neckar. Description based on drawings by Tobias Mayer from 1737, available in the Esslingen city archive.

Coordinates: 48 ° 44 ′ 35.2 " N , 9 ° 18 ′ 23.1" E