European Union climate policy

The climate policy of the European Union is a European policy field that aims to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius compared to the pre-industrial level and to transform European economies into a low carbon economy .

aims

With its climate policy, the EU aims on the one hand to reduce its own emissions of greenhouse gases ( mitigation ), for example through the emissions trading system that has been in place since 2005 . However, since the limitation of anthropogenic climate change can ultimately only be achieved on a global level, the EU is also actively involved in the negotiations within the framework of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change . The EU climate policy also pursues the goal of limiting the effects of climate change ( adaptation ), for example through disaster control measures in Europe or through conflict prevention in developing countries.

Climate policy has developed into one of the most dynamic policy areas in the EU in recent years. Organizationally, climate policy has long been part of the Environment Directorate-General. In the Barroso II Commission , the office of a Commissioner for Climate Protection was created for the first time , which is now independent of the Environment Commissioner .

Legal bases

EU climate policy began as part of EU environmental policy . It thus had its primary legal basis in the Single European Act , which came into force in 1987 and added provisions on the environment to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU, then called the EEC Treaty ), without explicitly mentioning the climate. Since 2009, environmental protection has also been included as a goal in the EU Treaty ; it obliges the European Union to achieve sustainable development and calls for environmental protection and improvement of environmental quality.

With the Lisbon Treaty in 2009, in the context of environmental protection, climate policy was also included in Art. 191 TFEU and thus expressly in primary law as the aim of “promoting measures at international level [...] in particular to combat climate change” . In addition, the energy policy objectives that were also included in the TFEU with the Lisbon Treaty - including the promotion of energy efficiency, energy savings and the development of new and renewable energy sources - are an important additional legitimation for EU climate policy measures.

Decisions on energy policy measures within the EU are generally made by the Council and Parliament in the ordinary legislative procedure in accordance with Art. 294 at the proposal of the Commission . In the case of measures that strongly interfere with the energy mix and the energy supply structure of the member states, the Council decides unanimously in accordance with TFEU Art. 194 , Paragraph 2; the European Parliament is only consulted in these cases. The same applies to interventions in land use .

Greenhouse gas emissions in the EU

As a member of the Framework Convention on Climate Change, the EU publishes data on greenhouse gas emissions in the EU countries since 1990. The greenhouse gas emissions of the EU-28 have fallen from 5.7 to 4.3 billion tonnes of CO 2 equivalent since 1990 . The emissions stem primarily from energy generation (56.8%), followed by transport (20.8%), agriculture (10.2%), industry (8.7%) and waste management (3.4%). Land use, land use changes and forestry saved 7.1% of the total emissions. Germany has the largest share of EU emissions with 21%, followed by the United Kingdom (12.2%), France (10.7%), Italy (9.8%), Poland (8.9%) and Spain (7.7%). Per capita emissions are highest in Luxembourg, Estonia and Iceland, and lowest in Romania. With 81%, CO 2 has the largest share of emissions, methane 10.6%, nitrous oxide 5.6% and fluorinated greenhouse gases 2.8%.

Fields of action

The EU climate policy takes its starting point in the European Climate Protection Program (ECCP) of 2000, which regulated the implementation of the commitments made under the Kyoto Protocol . Since then, EU climate policy has become more and more differentiated, and the number of climate policy fields of action has steadily expanded. EU climate policy received a particular boost with the first adoption of a European energy strategy in January and March 2007. In this context, it was determined that the EU wants to achieve a 20% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 (compared to the base year 1990). In 2011, the EU had the 20% target set at the UN level as part of the Kyoto II agreement.

The most important fields of action of EU climate policy are:

- Emissions trading ( EU-ETS )

- Greenhouse gas reductions beyond the emissions trading sector

- Engagement in the international climate negotiations

- Adaptation to climate change in the EU

- Climate protection as a preventive security policy

- Regulation of CO 2 emissions from cars and light commercial vehicles

- Promotion of the capture and storage of CO 2

- Increasing energy efficiency and promoting energy sources from renewable sources

The European Union also participates in UN climate conferences to develop global climate agreements and their sub-steps. At the UN Climate Change Conference in Warsaw in 2013 from November 11 to 22, 2013, the Environment Committee of the European Parliament submitted an application.

Climate and Energy Package 2020

The 2020 climate and energy package was adopted in 2007 and legislation was passed in 2009. Its three main goals, also known as the "20-20-20 Goals", are:

- 20% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (compared to 1990 levels)

- 20% of the energy in the EU from renewable sources

- 20% improvement in energy efficiency

The most important instrument for reducing emissions is the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), which covers around 45% of greenhouse gas emissions (large power plants and large industrial plants, aviation) in the EU. In 2020, the sectors concerned are expected to cause 21% fewer emissions than in 2005. In addition, national emission reduction targets apply to the remaining 55% of emissions (residential construction, agriculture, waste management, transport with the exception of air transport). As part of the burden-sharing decision , the goals of individual member states are between −20% (poorest countries) and +20% (richest countries). The sectors covered by national emission reduction targets are to reduce their emissions by a total of 10% compared to 2005. This target is lower than that for the sectors covered by the ETS, as emission reductions in the ETS sectors can be achieved at lower costs.

To increase the share of energy from renewable sources, the EU countries have set binding national targets within the framework of the directive on energy from renewable sources . These targets also vary depending on the starting position and ability of countries to increase energy production from renewable sources, from 10% in Malta to 49% in Sweden.

In addition, the EU supports the development of CO 2 low carbon technologies as part of the NER 300 program and the research funding program Horizon 2020 . Measures to increase energy efficiency are the energy efficiency plan and the energy efficiency directive .

Timetable 2050

In March 2011 the European Commission published the “Roadmap for the Transition to a Competitive Low Carbon Economy by 2050”. According to this, the EU should reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050 compared to 1990 levels. Reductions of 40% by 2030 and 60% by 2040 were named as milestones. According to the Commission all sectors as part of its technological and economic potential need to shift to a CO 2 contribute low carbon economy. The energy sector has the greatest potential for reduction. The fossil fuels in the transport and heating sectors could be partially replaced by electricity. The electricity should come from renewable sources such as wind, sun, water and biomass or other low-emission sources such as nuclear power plants or fossil power plants with technologies for the separation and storage of carbon dioxide. In the transport sector, according to the Commission, emissions could be reduced by more than 60% compared to 1990 levels (in the short term by improving fuel efficiency, in the medium to long term with plug-in hybrid and electric vehicles). In air and road freight transport (which cannot be completely converted to electricity) more biofuels should be used. The emissions from private and office buildings could be reduced by around 90% by 2050 (passive house technology in new buildings, targeted renovation of old buildings, replacement of fossil fuels for heating, cooling and cooking with electricity and renewable energy sources). According to the Commission, emissions in industry could be reduced by more than 80% by 2050, primarily through new technologies and gradual reductions in energy intensity, and after 2035 through technologies for capturing and storing carbon dioxide in certain branches of industry (steel, cement). With the growing global demand for food, the share of agriculture in total EU emissions will increase to around a third by 2050. However, emissions reductions are also possible here, agriculture must reduce the emissions caused by fertilizer, manure and livestock farming (also through a low-meat diet) and can also make a contribution to the storage of CO 2 in soils and forests. The Commission describes the roadmap as feasible and affordable. This transition would require 270 billion euros (or 1.5% of GDP annually) in additional investment over the next four decades.

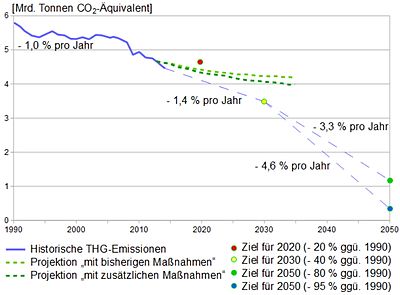

EU emissions fell by an average of 1% per year between 1990 and 2014 (see graph). In order to achieve the targets set in the roadmap, the average annual reduction in emissions must be at least 1.4% between 2015 and 2030 and 3.3% between 2030 and 2050.

Framework for climate and energy policy up to 2030

The framework for climate and energy policy up to 2030 was adopted in October 2014. It contains three main goals by 2030:

- Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40% (compared to 1990 levels)

- Increase in the share of renewable energy sources to at least 27%

- Increase in energy efficiency by at least 27%

In order to achieve the emissions target, the sectors covered by the ETS would have to reduce their emissions by 43% and sectors not covered by the ETS by 30% (0% to −40% depending on the country) compared to 2005 levels.

Proposal on national burden sharing for sectors outside the ETS

In July 2016, the European Commission published a proposal with binding national annual targets for the member states to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the period 2021-2030 for the sectors not covered by the emissions trading system (transport, buildings, agriculture, waste, land use and forestry). The burden sharing was designed on the basis of relative GDP per capita, but is supplemented by several flexibility mechanisms to increase cost efficiency. The proposal includes a reduction in emissions in 2030 compared to 2005 of 38% for Germany, 37% for France and the United Kingdom, 33% for Italy and 26% for Spain.

Proposal to include land use

In July 2016, the European Commission published the proposal according to which each member state must ensure that the recorded CO 2 emissions from land use are fully offset by measures in the same sector by removing a corresponding amount of CO 2 from the air (prohibition of Negative balance). The proposal contains flexibility options with which allocations from the burden sharing regulation can be used in order to meet obligations without a negative balance. Member States can also buy a net extraction from other Member States or sell their extraction. To a limited extent, the offsetting of credits (positive balance) for national targets in accordance with the burden sharing ordinance is provided.

Long-term strategic vision for a climate-neutral economy

On November 28, 2018, the European Commission published a strategy to make Europe the first economy in the world to become climate neutral by 2050. The Commission is in favor of full decarbonisation . In the future, the EU wants to make 25% of its budget available for climate protection measures. The Commission estimates the need for additional investment at EUR 175 to 290 billion annually. At the same time, the EU could save a lot of money by decreasing dependency on imported oil or gas: According to the Commission, the Europeans are currently paying 266 billion euros per year to their energy suppliers, around 70 percent of which could be saved. In addition, the cost of health damage caused by air pollution could be reduced by more than 200 billion euros per year.

At the EU summit in June 2019, no agreement was reached on a commitment to climate neutrality by 2050, as Poland in particular, but also Hungary, the Czech Republic and Estonia opposed it.

On 11 December 2019 with the European Green Deal ( European Green Deal ) by the European Commission , Ursula von der Leyen presented concept with the goal of reducing by 2050 in the European Union, the net emissions of greenhouse gases to zero and thus as first continent to become climate neutral .

See also

literature

- Peter Vis, Jos Delbeke : EU Climate Policy Explained . European Commission, Brussels 2015. ISBN 9279482610 (PDF; 2.2 MB) .

- Michal Nachmany u. a. Climate Change Legislation in European Union - An Excerpt from: The 2015 Global Climate Legislation Study - A Review of Climate Change Legislation in 99 Countries. Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, 2015. (PDF; 650 kB) .

Web links

- Climate Policy - Topic Page of the European Union

- General Directorate Climate of the EU Commission

- Tim Rayner and Andrew Jordan: Climate Change Policy in the European Union. Entry in the Oxford Research Encyclopedia - Climate Science , August 2016, doi : 10.1093 / acrefore / 9780190228620.013.47 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b The Challenge of Climate Change , Science and Politics Foundation (SWP), undated

- ↑ a b The climate policy of the European Union , University of Kiel, November 1, 2011

- ↑ International Climate Policy , Federal Agency for Civic Education (BpB), 23 May 2013

- ↑ Climate policy in the European Union ( Memento of the original from July 22, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Tyrol - Brussels Office, April 17, 2012, p. 3

- ↑ Commission is reorganizing , Deutscher Naturschutzring, EU coordination, 2010

- ↑ The new European Commission: Barroso's second occupation ( Memento of the original from April 25, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Deutscher Naturschutzring, EU coordination, February 2010

- ↑ Energy and climate policy in the Treaty of Lisbon: Legitimation extension for growing challenges , by Severin Fischer, Institute for European Politics, Berlin, no date.

- ↑ Single European Act , Title II, Chapter II, Section II, Subsection VI - Environment, Article 25. In: Official Journal of the European Communities, No. L 169/4 of June 29, 1987, to supplement Article 130r (now Article Art . 191 ).

- ↑ Vis and Delbeke: EU Climate Policy Explained . 2015, p. 9 .

- ↑ EU Treaty Art. 3 , Paragraph 3.

- ↑ Integrated Energy and Climate Policy - Plans and Problems , by Gerhard Öhlmann, Leibnitz Institut Lifis, March 10, 2008, p. 12

-

↑ Treaty of Lisbon amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community. Environment section (climate change), Article 143 amending Article 174a. In: Official Journal of the European Union, Volume 50, December 17, 2007, 2007 / C 306/01.

Resulting consolidated version of the TFEU: Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union , Title XX "Environment", Article 191 (formerly Article 174 of the EC Treaty) - ↑ TFEU Art. 194 . See also Severin Fischer: Energy and climate policy in the Treaty of Lisbon: Legitimacy expansion for growing challenges . In: integration . 2009 ( iep-berlin.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Groundbreaking resolutions in times of European and international crises , by Joscha Ritz and Olaf Wientze, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, European Office Brussels, 24./25. March 2011, p. 9

- ^ Council formations - the Councils of Ministers , Deutscher Naturschutzring, EU coordination, accessed on July 22, 2016

- ^ According to the Paris Climate Agreement , by Susanne Dröge and Oliver Geden, Science and Politics Foundation (SWP), March 2016, p. 4

- ↑ Art. 192 , Paragraph 2b).

- ↑ European Environment Agency: Data viewer on greenhouse gas emissions and removals, sent by countries to UNFCCC and the EU Greenhouse Gas Monitoring Mechanism (EU Member States). Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- ↑ Oliver Geden: The implementation of the "Kyoto II" obligations in EU law. Increasingly narrow scope for Germany to play a pioneering role in climate policy. (PDF; 101 kB) Retrieved April 6, 2015 .

- ↑ motion for a resolution B7-0482 / 2013 , Environment Committee , European Parliament, October 16, 2013. Accessed October 20, 2013.

- ↑ a b c d Climate and Energy Package 2020

- ↑ For the term “20-20-20 goals” see for example: International and EU climate policy. Federal Environment Agency, April 13, 2016, accessed on October 19, 2018 .

- ↑ Jos Delbeke, Peter Vis: EU Climate Policy Explained . 1st edition. Routledge, 2015, ISBN 978-92-79-48263-2 , pp. 136 .

- ↑ Low-carbon economy by 2050 . European Commission, July 22, 2016. Accessed August 4, 2016.

- ↑ European Environment Agency: Trends and projections in Europe 2015. EEA Report No. 4/2015.

- ↑ a b Framework for climate and energy policy up to 2030

- ↑ Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council setting binding national annual targets for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in the period 2021-2030 in order to create a resilient Energy Union and fulfill the obligations from the Paris Agreement and to amend Regulation (EU) No. 525/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council on a system for monitoring greenhouse gas emissions and for reporting these emissions and other information relevant to climate protection . 20th July 2016.

- ↑ Energy Union and Climate Policy: Setting the course for Europe's transition to a low-carbon economy . Press release, European Commission, July 20, 2016.

- ↑ Factsheet on the Commission's proposal to set binding national targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions (2021–2030) . European Commission, July 20, 2016.

- ↑ Proposal for including land use in the framework for EU climate and energy policy up to 2030 . European Commission, July 20, 2016.

- ↑ Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions and the European Investment Bank. A Clean Planet for all - A European strategic long-term vision for a prosperous, modern, competitive and climate neutral economy. European Commission, November 28, 2018, accessed on November 28, 2018 .

- ↑ CO2 emissions: With this plan, Brussels wants to make Europe climate neutral by 2050 . ( handelsblatt.com [accessed November 28, 2018]).

- ↑ Christoph G. Schmutz: The EU wants to become climate neutral . In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . November 28, 2018, ISSN 0376-6829 ( nzz.ch [accessed November 28, 2018]).

- ↑ CO2-neutral Europe by 2050: New climate target failed at EU summit. In: n-tv. June 20, 2019, accessed June 22, 2019 .