Concretism (psychology)

In psychology, concretism is understood as the difficulty of certain people in using generic terms (see → Ability to abstract ). Concretism is also defined as the alignment of thoughts and feelings, in particular, with reality that is sensually tangible and vivid .

People affected by concretism have to use the paraphrasing by means of an example to describe their thoughts, just as children do at certain stages of their language development (materialized logic). (a)

Concretism in Complex Psychology

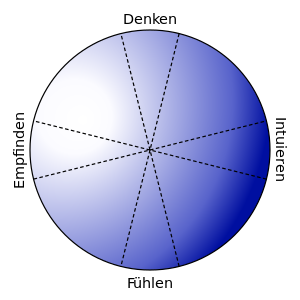

According to Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961), concretism is understood as an opposition to abstraction . According to Jung, it is primarily a question of an overvalue of the sensory function. This superior function characterizes the sensation type, cf. the lighter left half of Fig. 1. In addition, there is a peculiarity of thinking and feeling . Concretely means something like "grown together" ( Latin concrescere ). In the case of concretistic thinking , a term is presented as "fused" or fused with other sensual visual material. In this respect, such a concept is bound and attached to this material and thereby does not gain any abstractive and individual freedom. Individual internal factors would thus find no possibility of impartial expression, but would rather be projected into external facts . Concreteist thinking is not about the use of differentiated terms. (a) - According to George Eman Vaillant , projection is one of the most immature defensive processes. (a)

According to Jung, the thinking of so-called indigenous and indigenous peoples (or “primitive peoples” from the earlier western perspective) does not show any “separate independence”, but rather rises to the level of analogy . The fetishism is a concretism therefore, not for the subjective or inner emotional state will experience, but this in an external object - such as a sacred tree would be moved into or projected -. (b)

Concretism is also an archaism (see section Developmental Psychology ). Jung places concretism under the more general term “mystical participation” ( participation mystique ) according to Lévy-Bruhl (1857–1939). (c) He was a contemporary of Freud, but independently from him, as an ethnologist , he dealt with social issues. The term "participation" comes from one of his writings, which appeared in 1910. Among other things - also independently of Freud - he called the "primitive" forms of thinking prelogic , see also Freud's theory of materialized logic (see above - opening credits ). Freud first dealt with the ethnological parallels in his teaching, psychoanalysis , in his work Totem and Tabu (1912/1913) and specifically with Jung's views. Until then he understood his teaching mainly as individual psychology .

According to Jung, “mystical participation” represents a mixture of inner psychological factors with external objects. Concretism also embodies a mixture of thinking and feeling with sensation . It is a superstitious overestimation of mere facts, which also leads to hypostasis . It is true that the recognition and orientation to facts is valuable, but it does not yet allow these facts to be interpreted . The concretistic thought sticks to the material appearance. With this, Jung also outlines the development of feelings and thinking, at least hinted at below, the meaning of which lies in a liberation from the binding of soul energy to the merely misunderstood perception . The idea arises through the elimination of the necessary concretism from the merely pictorial experience - and this also includes the primeval images . (d)

Jung goes on to explain elsewhere that the superstitious attitude can be seen as a consequence of the inferiorly developed intuitive function, see also the dark right half in the diagram of the psychological functions in Fig. 1 “Personality typology”. The part of the intuitive functions that remains unconscious is forced upon the senses (passive apperception ). Feeling and thinking are also influenced by this dynamic.

Developmental psychology

Developmental psychology describes the long-lasting, successive changes in human experience that lead to an increase or decrease in abilities in a human life that is not biologically determined by disease .

Neuroanatomy and Sensory Psychology

According to the basic biogenetic and psychogenic law , the early stages of ontogenetic development of modern humans correspond to the more mature stages of an individual in the early universal or human history . Conversely, the level of development of an adult in the early stages of human development would correspond to that of an adolescent in the present day. It is therefore to be assumed that there is a development gap that cannot justify a value judgment, as is often associated with the term “primitive cultures”. In short, the ontogeny of modern humans not only recapitulates the entire phylogeny , but also the human tribal history . Given this prerequisite, the aforementioned development principle is particularly important for the entire neuroanatomical development. Since the primary (or “primitive”) sensory centers are first myelinated in the ontogenetic development of humans , the concretism in children (see above opening credits ) is neuroanatomically understandable and justifiable as a lawful development according to the universal history of humans. Accordingly, it can be assumed that the nervous system in adults was also appropriately equipped in the early stages of human development. It would be, for example, the participation mystique observed in indigenous peoples and the associated alignment of thinking and feeling with reality, which is directly tangible and tangible, and so on. a. The myelination is also to be regarded as conditioned by the neuroanatomical conditions.

Desomatization and resomatization

Stavros Mentzos (1930–2015) understands concretization as a mode of coping with diffuse fear. This fear is related or concretized to very specific organs in order to convert diffuse fear into concrete fear in this way. So z. For example, a diffuse fear can be converted into a concrete fear of dying of cardiac death, although there are primarily no or only minor disturbances of the heart's activity ( heart neurosis ). Since it is assumed that feelings such as fear develop from originally purely physical conditions or from innate vegetative attitudes , attention must be paid to undifferentiated sensations close to the body such as the feelings and conditions described as zoenesthesias as a possible starting point for the development of very simple sensations to highly differentiated feelings. (b) Max Schur (1897–1969) dedicated himself to this task and established his theory of desomatization or its regressive reversal in the form of resomatization. This teaching says that there is probably an ongoing process of the development of feelings, ranging from indeterminate and body-hugging, reflex-unconscious arousal processes such as subliminal pleasure and displeasure, dizziness or nausea to very differentiated feelings such as joy, trust, faith , Love, hope extend. The latter require a differentiated ability to form symbols. The development does not take place in a social empty space, but is exposed to the manifold influences of the environment, such as those of caregivers or complex cultural factors. However, such influences can also be traumatic . In organ neuroses such as the cardiac neurosis mentioned, it can be assumed that resomatization plays a regressive role. The maturation processes described above, such as myelination, are therefore not to be regarded as a legally determined and uniform process, but take place within the framework of the most varied of environmental influences. (c) (b) Since we are not dealing with automatic maturation processes, it is easy to understand that the inferior functions of the intuitive, mentioned above using the example of superstition, also have an effect on the auxiliary functions of thinking and feeling.

Judgment

According to Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) the power of judgment has to distinguish whether something is subject to a certain rule or a general principle or law. Kant thereby distinguishes the thinking or reflective judgment from the subsuming . The latter can be understood as the ability to form generic terms. It makes a decision and comes to a certain result. The former considers the fact to be decided in each case. With regard to the “communicability of a sensation” (Section 39 KdU), Kant explains that it can only have a claim to knowledge and thus also to communication if it is not only purely subjectively determined, ie. H. neither of criteria of pleasure and convenience nor, on the contrary, of a deterrent character or discomfort. A “supersensible determination” of these sensations is presupposed by Kant, which corresponds to the moral disposition and laws of man and is based on taste . Matter must not be taken for form, stimulus not for beauty. A meaning is assigned to what Kant calls “real perception” ( stimulus ) . Kant called this sensation . This is necessary in order to search for a judgment that should serve as the general rule. This is the only way to speak of common sense, a sense of community or sensus communis , which is freed from subjective private conditions (§ 40 KdU). However, in order to avoid the subjective sources of error indicated here, it is necessary to reflect “oneself” while observing the natural rules ( understanding ) and to think “together with others” (judgment). The maxim of reason follows from both . - Kant describes predominantly external determination by others as superstition ( heteronomy ). A persistence in subjective circumstances is defined by Kant as restricted or “narrow-minded”. Enlightenment required an expanded thinking with liberation from superstition.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Uwe Henrik Peters : Dictionary of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology. 3. Edition. Urban & Schwarzenberg, Munich 1984, p. 119 on article "Thinking, concrete".

- ^ Concretism. In: Markus Antonius Wirtz (ed.): Dorsch - Lexicon of Psychology . 18th, revised edition. With the collaboration of Janina Stohmer. Hogrefe, Bern 2017, ISBN 978-3-456-85643-8 ( online ).

-

↑ a b Sven Olaf Hoffmann , G. Hochapfel: Theory of Neuroses, Psychotherapeutic and Psychosomatic Medicine (= compact textbook ). 6., rework. and exp. 1st edition, anniversary edition. Schattauer, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-7945-1960-4 (first edition: 1999): (a) p. 206 on the keyword “Primary process-based thinking in the course of child development”, (b) p. 206 on head. “Resomatization”.

-

↑ a b c d Carl Gustav Jung : Definitions. In: Collected Works. Volume 6: Psychological Types. Walter-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1995, ISBN 3-530-40081-5 , p. 479 ff. §§ 766-769 to chap. “Concretism”: (a) p. 479, § 766 on the keyword “Adherence of concrete terms to visual material conveyed through the senses”; (b) p. 480, § 767 on tax “Example fetishism”; (c) p. 480 § 767 on tax “anarchism”; and p. 447 ff. §§ 694 ff. on chap. "Image" or to Stw. "Primitive image"; (d) p. 448 f. § 695 f. to Stw. "primeval image as a preliminary stage of the idea".

-

↑ a b c Stavros Mentzos : Neurotic Conflict Processing. Introduction to the psychoanalytic theory of neuroses, taking into account more recent perspectives (= Fischer Taschenbuch. Geist und Psyche. Volume 42239). Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt 1992, ISBN 3-596-42239-6 (first edition: Kindler, Munich 1982): (a) p. 62 ff. On the keyword “defense mechanisms”; (b) pp. 34, 173, 176, 177 178 on “heart neurosis”; (c) pp. 34, 61 f., 174 f. to Stw. "Concretization" and "Resomatization".

- ↑ George Eman Vaillant : Theoretical Hierarchy of Adaptive Ego Mechanisms. In: Archives of General Psychiatry . 24 (2), 1971, pp. 107-118, doi: 10.1001 / archpsyc.1971.01750080011003 .

- ↑ Lucien Lévy-Bruhl : Les fonctions mentales dans les sociétés inférieures. Les Presses universitaires de France, Paris 1910; 9th edition. 1951, doi: 10.1522 / cla.lel.fon .

- ^ Karl-Heinz Hillmann : Dictionary of Sociology (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 410). 4th, revised and expanded edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-520-41004-4 , p. 489 to Lexicon-Lemma : "Lévi-Bruhl" (read: Lévy-Bruhl ), Stw. "Prelogik".

- ↑ a b superstition. In: Carl Gustav Jung: Collected works. Walter-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1995, special edition, volume 6: Psychological types. ISBN 3-530-40081-5 , pp. 391, 481, 499 - §§ 608, 769, 803; Volume 11: On the psychology of western and eastern religion. ISBN 3-530-40087-4 , p. 603 - § 1004.

- ↑ Ernst Haeckel : General Morphology of Organisms. 2 volumes. Georg Reimer, Berlin 1866 (digital copies: Vol. 1 , Vol. 2 ).

- ↑ Paul Flechsig : Anatomy of the human brain and spinal cord on myelogenetic basis. Thieme, Leipzig 1920, DNB 365828440 .

- ↑ Max Schur : Comments on the metapsychology of Somatization. In: The Psychoanalytic study of the Child. 10 (1955), ISSN 0079-7308 , pp. 119-164 ( beginning of the article ).

- ^ Thure von Uexküll : Psychosomatic Medicine. 3., rework. and exp. Edition. Edited by Rolf Adler. Urban & Schwarzenberg, Munich / Vienna / Baltimore 1986, ISBN 3-541-08843-5 (incorrect), DNB 851002188 , p. 51 f. to Stw. "Role of vegetative regulations in desomatization and resomatization".

- ^ Heinrich Schmidt : Philosophical Dictionary (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 13). 21st edition. Revised by Georgi Schischkoff . Alfred Kröner, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-520-01321-5 , p. 720 on Lemma “judgment”.

- ↑ See also the connection between pleasure in the section on desomatization and resomatization on the question of the differentiation of feelings.

- ↑ Immanuel Kant : Critique of Judgment (= Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft ). Edited by Wilhelm Weischedel . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt / M. 1995, ISBN 3-518-09327-4 , text and pages identical to vol. X of the work edition, pp. 222–226, KdU B 153–158, § 39–40 (first edition: 1790).