Labyrinthodontia

The division of living beings into systematics is a continuous subject of research. Different systematic classifications exist side by side and one after the other. The taxon treated here has become obsolete due to new research or is not part of the group systematics presented in the German-language Wikipedia.

The labyrinthodontia ( labyrinth teeth , out of date also winding teeth ) or stegocephalia ( roof skull , roof skull lurch from ancient Gr . Stégos "roof", cephale "head") are in the classical biological system a group of extinct primitive land vertebrates (tetrapoda), which from the late Devonian (before approx 400 million years ago) existed until the early Cretaceous (approx. 120 million years ago) and was widespread worldwide. In the sense of modern systematics , however, they are not a natural family group. The labyrinthodontia owe their name to the enamel layer of their teeth that is folded like a labyrinth in cross section . In the German-speaking countries they are also known under the common name " Panzerlurche ".

Systematics

The term 'labyrinthodontia' does not designate a valid taxon in the sense of modern systematics (therefore in the following put in quotation marks), but is z. Some are still in use in the literature. The term “Stegocephalia” or “Stegocephali”, on the other hand, describes a monophyletic group that includes all living and extinct tetrapods as well as some of their still quite fish-like ancestors and is the sister group of the fish-like meat- fin fish Panderichthys . The links between the bony fish and all terrestrial vertebrates were also classified under the term “labyrinthodontia” .

The genera that were formerly part of the "Labyrinthodontia" are now placed in other groups, especially the Temnospondyli (the Temnospondyli themselves were listed as a subgroup of the Labyrinthodontics at that time). Some former labyrinthodonts groups do not form a natural affinity group in the sense of the modern system, but merely as a species and genera on the same stage of evolution (to Engl ., Grade ') are, understood what applies primarily to the very early tetrapods (see also → Evolutionary Aspects ). It should be added that the system of the groups previously referred to as “labyrinthodontia” is still relatively unstable and varies more or less from author to author.

"Labyrinthodontia" are due to their geological age and appearance z. B. in exhibitions of prehistoric animals often placed next to contemporary reptiles, although they systematically do not belong to the reptiles. As a collective term for both prehistoric amphibians and reptiles, the rather common term " dinosaur " has become established.

Characteristics, ecology and importance of the group

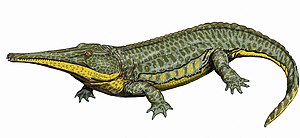

The earliest "labyrinthodontia" contain those vertebrates that were able to use dry terrain as a habitat, at least temporarily. Some later representatives, however, had adapted strongly to country life and were possibly sharp competitors of the early amniotes (e.g. Cacops ). In addition to the labyrinthine-like folded dentin layer of the teeth, one of the typical features that gives the group its other scientific name, "Stegocephalia" ("Stegocephalia" ), is the strongly ossified, compared to the bony fish, firmly attached to the cranium (but detached from the shoulder girdle) and also windowless Dachschädler "). The German name "Panzerlurch" refers on the one hand to the compact skull structure, on the other hand to the bone plates that some representatives of the "labyrinthodontia" had embedded in the dorsal skin (so-called osteoderms ), very similar to what is the case with today's crocodiles. Another typical feature relating to the skull is its parabolic shape when viewed from above . Some labyrinthodontics, such as B. Platyoposaurus , however, had relatively elongated jaws.

The representatives of the "Labyrinthodontia" reached sizes from that of a salamander to that of a large crocodile. The way of life of many large labyrinthodont animals is likely to have been similar to that of today's large crocodiles: They lurked in the shallow water near the shore for prey that came to drink in the water. Others may have lurked in deeper water at the bottom for smaller labyrinthodont animals or larger fish swimming past. The smaller forms likely fed on either small fish or insects.

However, the reproduction of the "Labyrinthodontia" was similar to that of today's frogs and salamanders: The shell-less eggs were released directly into the water and the juvenile stages lived gill-breathing in the water and only formed lungs at the transition to the adult stage, which made them independent of the water environment and gave them one amphibious, e.g. Partly also enabled a fully terrestrial way of life.

Evolutionary Aspects

The "Labyrinthodontia", like all tetrapods, come from a fish-like flesh fin (Sarcopterygii). This is made clear in particular in the Devonian sedimentary rocks of North America and Scotland . Fossils of very primitive labyrinthodontic animals, which were grouped under the term “ Ichthyostegalia ” (“fish skull lurch”). These representatives, which were still quite fish-like, had four legs, but had many of the characteristics of the fish-like meat-finfish (including the formation of the tail or the arrangement of the bones of the skull). This group also gained a certain fame outside of paleontology and evolutionary biology, as it represents the evolutionary link between fish and amphibians as well as all other, primarily terrestrial vertebrates ( amniotes ).

The systematic case of the "Ichthyostegalia" is, by the way, similar to that of the labyrinthodontists as a whole. According to the modern view, they do not form a self-contained group, but rather represent a certain stage of development in the evolution of the tetrapods, with some representatives being more closely related to the tetrapods living today than to other Ichthyostegals.

Footnotes

- ^ Brockhaus' Kleines Konversations-Lexikon. Fifth edition, Volume 2, Leipzig 1911, p. 979 ( online )

- ^ Warren, Rich, Vickers-Rich: The last labyrinthodonts?

- ↑ Lexicon of Biology - "Panzerlurche" Wissenschaft-online.de - Spectrum Academic Publishing House . Last accessed on January 13, 2013.

- ^ Laurin et al.: Early Tetrapod Evolution.

- ↑ an exception to this is the representative Nycteroleter , classified by Carroll (1988) as a labyrinthodont animal , but later identified as a parareptile (see e.g. Ivakhnenko, 1997)

- ↑ Reisz et al: The armored dissorophid Cacops from the Early Permian of Oklahoma

- ↑ Labyrinthodontic teeth are not a unique selling point of the labyrinthodontic animals, but are already found in their fish-like predecessors.

- ↑ Representation after A. Portmann, p. 38 ff. And AS Romer, p. 61 ff.

- ↑ cf. A. Portmann, p. 38.

literature

- Robert Lynn Carroll : Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. WH Freeman and Co, New York 1988.

- Mikhail F. Ivakhnenko: New Late Permian Nycteroleterids from Eastern Europe. In: Paleontological Journal. Vol. 31, No. 5, 1997, pp. 552-558.

- Michel Laurin, Marc Girondot, Armand de Ricqlès: Early Tetrapod Evolution. In: Trends in Ecology and Evolution. Vol. 15, No. 3, 2000, pp. 118-123.

- Adolf Portmann : Introduction to the comparative morphology of vertebrates. 5th, revised edition. Basel / Stuttgart 1976, ISBN 3-7965-0668-2 .

- Robert R. Reisz, Rainer R. Schoch, Jason S. Anderson: The armored dissorophid Cacops from the Early Permian of Oklahoma and the exploitation of the terrestrial realm by amphibians. In: Natural Sciences. Vol. 96, No. 7, 2009, pp. 789-796, doi: 10.1007 / s00114-009-0533-x .

- Alfred Sherwood Romer : Comparative Anatomy of the Vertebrates. 4th edition. Paul Parey Publishing House, Hamburg / Berlin 1976, ISBN 3-490-07018-6 .

- AA Warren, TH Rich, P. Vickers-Rich: The last labyrinthodonts? In: Palaeontographica. Division A, Vol. 247, 1997, pp. 1-24.