Lithopedion

A lithopedion ( ancient Greek λιθοπαίδιον , λίθος lithos 'stone' and παιδίον paidion 'child'), also stone child or stone fruit , is a dead, petrified fetus in the womb.

Emergence

A lithopedion arises when a dead fetus of a ectopic pregnancy , an ectopic pregnancy or uterine rupture, as usual, by the body not absorbed (such as common in embryos before the third month), but by incorporation of lime encapsulated and mummified is. The existence of a petrified fetus in the mother's body can cause symptoms such as pelvic pain, but it can also be asymptomatic. Surgical removal of the stone fruit is advisable to avoid complications. Occasionally, however, a stone fruit is only discovered after the mother's natural death.

The formation of lithopedions is extremely rare in humans, less than 300 cases have been documented to date. In multiparae the phenomenon is more common, especially in domestic swine .

Stone child from Sens

Madame Colombe Chatri from Sens (Burgundy) showed all signs of normal pregnancy in 1554 at the age of 40 , but the child was not born. The mother was bedridden for the next three years and continued to suffer from pain. The unborn child could be felt as a hard swelling in her body. After her death in 1582, the widower had her dissected. A large egg-like structure was found in the mother's womb that could only be broken open by force. Inside was a petrified girl at full term.

Steinkind from Leinzell

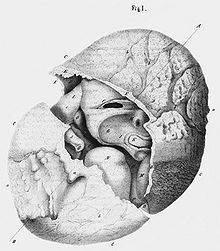

Anna Mullern (or Müller), the mother of the lithopedionist von Leinzell , was in labor for seven weeks in 1674, but could not give birth to the child. The stone fruit remained in her body, later she gave birth to a son and a daughter. She hired the local doctor, Dr. Homely, as well as the Bader Mr. Knauffen (or Knaus) from Heubach , to open their body after their death and to get the child out. Since the woman, who lived to be 91 years old according to the University of Tübingen and 94 according to Jan Bondeson , survived her doctor, the Bader autopsied her initially without medical assistance. He found a well-preserved lithopedion of a male fetus and called in the doctor Johann Georg Steigerthal , who made the first description and drawing of the Steinkind von Leinzell . The child of Anna Mullern (or Müller) has been preserved in contrast to the Steinkind von Sens and is now in Tübingen .

The "Nebelsche Steinkind"

Daniel Wilhelm Nebel , physician, chemist and rector of Heidelberg University , made the discovery of a lithopedionist, later known as the “Nebelsche Steinkind”, in the course of an autopsy on the late Susanne Stolberg (1675–1767), the wife of a Heidelberg high school professor has been. The womb, which had almost been carried to term, was not born, but got through a rupture into the abdominal cavity, where it died. There she was impregnated with calcium salts and remained in the woman's abdomen for 54 years.

Nebel summarized his findings on this in the essay " fetus ossei per quinquaginta quatuor annos extra uterum in abdomine detenti historia ", which he published in 1770 in the Acta Academiae Theodoro-Palatinae in Mannheim . The rare specimen is owned by the University's Pathological Institute.

literature

- R. Passini, R. Knobel, MA Parpinelli, BG Pereira, E. Amaral, FG de Castro Surita, CR de Araújo Lett: Calcified abdominal pregnancy with eighteen years of evolution: case report. In: São Paulo medical journal = Revista paulista de medicina. Volume 118, Number 6, November 2000, pp. 192-194, ISSN 1516-3180 . PMID 11120551 .

- J. Bondeson: The earliest known case of a lithopaedion. In: Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. Volume 89, Number 1, January 1996, pp. 13-18, ISSN 0141-0768 . PMID 8709075 . PMC 1295635 (free full text).

- JA Perper: Time of Death and Changes after Death. Part 1: Anatomical Considerations. In: WU Spitz, DJ Spitz (Ed.): Spitz and Fisher's Medicolegal Investigation of Death. Guideline for the Application of Pathology to Crime Investigations. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, Illinois, 2006 4 , p. 118.

- BM Rothschild, C. Rothschild, LC Bement: Three-millennium antiquity of the lithokelyphos variety of lithopedion. In: American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology . Volume 169, Number 1, July 1993, pp. 140-141, ISSN 0002-9378 . PMID 8333440 .

- HP Schmitt, W. Rosendahl: The Heidelberg Lithopädion ("Foetus Ossei") - for the mummification of a human fetus in the abdominal cavity by ossification. In: A. Wieczorek, W. Rosendahl, H. Wiegand (eds.): Mummies and museums. Mannheimer Geschichtsblätter, special volume 2, Heidelberg 2009, pp. 135-138.

Web links

- Steinkind von Leinzell in the anatomical collection of the University of Tübingen

- Fetus discovered in an 82-year-old. "Steinkind" was 40 years in the stomach n24.de, December 12, 2013

Individual evidence

- ^ Leo-Clemens Schulz (ed.): Pathology of domestic animals. Part I: Organ changes, Gustav Fischer Verlag Jena 1991, p. 628

- ↑ Both the name of the mother and that of the bather have come down to us in different forms. Bondeson, using the Mullern and Knauffen forms, may have been deceived by inflected forms and German script. The name Müller is mentioned in the location description of the Oberamt Gmünd and a newspaper article ; the newspaper article also calls Bader Knaus. There is also different information about the age of the woman and the sex of the two children born afterwards.

- ↑ Jan Bondeson : The earliest known case of a lithopaedion . In: Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine . 89, No. 1, January 1996, p. 47. PMID 8709075 . PMC 1295635 (free full text).

- ↑ Eberhard Stübler: The Nebelsche Steinkind and the Nebel family of doctors. In: Archives for the History of Medicine. Volume 18, Issue 1, (March 31) 1926, pp. 103-106.