Praise to folly

Moriae encomium to German: Praise of Folly (or Praise of Folly ) is the title of one of the most famous works of the Dutch humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam . The plant is also known as "Laus stultitiae".

History of origin

Erasmus wrote his work in 1509 while staying with his friend Thomas More in England. Years earlier (1506) Erasmus had already adapted satirical texts by the Hellenistic satirist Lukian of Samosata (120-180), who was later also called the Voltaire of antiquity, and published them - together with Thomas More - as the Luciani opuscula collection of works .

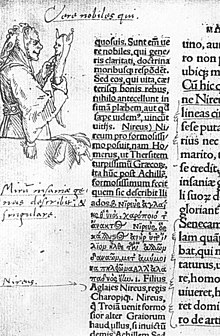

The praise of folly , written in Latin as an ironic discourse, was first printed by Jehan Petit and Gilles de Gourmont in Paris in 1511, and shortly thereafter, dated August 1511, by Matthias Schürer in Strasbourg. It was published in a new edition in 1515 by Johann Froben in Basel and with 83 hand drawings by the painter Hans Holbein the Elder. J. illustrated. It became one of the most widely read books in world literature. Erasmus dedicated the work to his friend Thomas More:

"Well, above all I thank your name Morus for the idea, which is just as similar to the name of Moria as you are dissimilar to her being [...] And then I believe that you will especially like such a game of imagination; Because a joke like this - I hope it is neither vulgar nor pointless everywhere - was always a lot of fun for you, and anyway you look at human activity with the eyes of a Democritus, only that you have a sharp mind that takes you far leads away from the popular views, at the same time you are the most sociable, cosiest person who is able to go into everything with everyone and loves. So this little exercise in style as a souvenir of your college friend will not be unwelcome to you. But you will also hold your hand over it, because it is dedicated to you and it is yours now, not me. "

The praise of folly was translated into many European languages during Erasmus's lifetime, for satires were the preferred literature of the educated during the Renaissance .

content

Stultitia takes a chair as a woman with a “bad reputation” , admits herself as personified folly and praises her “ virtues ” with relish . The first sentences of the book immediately clarify the intention of Erasmus:

“The folly appears and says: May people all over the world say what they want of me - I know how bad even the worst fools talk about folly - it remains: Me, yes, me all alone and mine Gods and people have strength to thank when they are cheerful and cheerful. "

In an ironic exaggeration , Erasmus lets “his” world ruler Stultitia , who has subjugated the world with her daughters to self-love, flattery, forgetfulness, laziness and lust (the so-called deadly sins ), praise herself, and aims at the stupid and with rhetorical elegance Vice of the people. Without further ado Stultitia clearly reads the astonished audience (reader), the Levites , takes devout Christians, merchants, princes, lawyers, monks, servants of God, saints and scholars on the grain and records fancy way a reflection of the time:

“What you get to hear from me is just a simple impromptu speech, artless, but honest. And don't mean to me that what I'm saying is a lie in the manner of a speaker, just to let my genius shine. You know that: if someone pays attention to a speech that he has pondered for thirty years - it is often stolen too - he swears to you that he wrote it down or even dictated it in three days as if playing. Oh no - I have always loved to say everything that comes on the tongue of stupid people. Just don't expect me to define myself or even plan myself according to the template of ordinary speakers. Both would be a bad start, because a force that works all over the world cannot be captured in any formula, and a deity cannot be broken up into which all creatures come together. "

The fictional speaker explains to the audience, who with her "mishmash of words", following the example of the scholars criticized by her, arbitrarily selects quotations from poetry, philosophy and theology and interprets them in their sense, i. H. falsifies the fact that, above all, the foolish and the stupid have a beneficial and beneficial effect on the coexistence of people. Wherever she appears, joy and happiness reign, they are all indebted to her, because she has always generously distributed her gifts - even without being asked - to everyone (that no person can lead a comfortable life without my consecration and favor):

All people (that appearances [...] are more captivating than the truth) of the individual nations (a kind of collective self-love), whether young (is being young something other than rash and irrationality) or old (the closer they get to old age, to so more they come back to childhood), women (in love the girls are clearly attached to gates with all their hearts, the wise avoid and abhor them like a scorpio) and men (I advised him according to my own way: he should join in Take wife, that stupid and silly as well as delightful and delightful creature), v. a. the common people (like [...] those who live happiest, to whom the arts are completely alien and who only follow the instinct of nature), but also clergy or men of the world (that they are all concerned about their advantage and that no one lacks knowledge of the law . […] One wisely shifts any burdens onto other people's shoulders and passes them on like a ball from hand to hand), whereby the “spiritual” and “the people” are in an “unbridgeable contrast of views [...] consider each other crazy ”, merchants (the most repulsive of all businesses), poets (self-love and flattery are peculiar to this bunch), writers (he writes whatever comes to his mind without much preparatory work), rhetors (with jugglers in the Apprenticeship), lawyers (they can argue about the emperor's beard with persistent doggedness and mostly lose sight of the truth in the heat of the moment), grammarians (in their treadmills and torture chambers -, i am in the midst of the bunch of children, aging ahead of time), scientists (what does it matter if someone like that dies who has never lived?), philosophers (little […] useful for any tasks in daily life […] - you pretend as if they had looked behind the secrets of nature's creator and had come to us directly from the council of the gods), religious people and monks (they consider it the epitome of pious change to neglect education to the point of ignorance of reading), theologians (They describe what the crowd does not understand as acumen [...] - pick up [...] four or five words here and there, distort them as necessary and make them bite-sized), Pope and Cardinals (Instead, they are extremely generous in interdicts , Impeachments, threats of ban), bishops (in the competition for ecclesiastical offices and benefices, a buffalo is more likely to prevail than a wise man), princes or kings (to cup the citizens and put the state income into their own T to lead ashes [...] even the grossest injustice still appears under the appearance of justice [...] - if someone [...] wanted to think about it [...], wouldn't he lead a sad and restless life?). All in all, this results in a crazy world (human life as a whole is nothing more than a game of folly [...] - one madman laughs at the other and they give each other pleasure) in which only "folly [...] freedom "Creates by diverting the gaze of the human being (from a high point of view [...] [would see] human life entangled in immeasurable disaster) from the" great misery "(it is this deception that keeps the eyes of the audience spellbound [...] - that just means being human!):

"It's just so good to have no sense that mortals would rather ask for deliverance from all kinds of hardships than for deliverance from folly."

Erasmus wrote his “exercise in style” in just a few days as a continuous work without chapter headings, conceived as an approximately three-hour speech (today printed on about 100 DIN A5 pages). Even without chapter headings, the structure of the work can be clearly recognized and divided as follows: The folly appears • It reports on its conception and its advantages • It praises the young and old • The folly blasphemes the gods • It explains the difference between Man and woman • What she thinks of friendship and marriage • About art, war and wise men • Follies about prudence, wisdom and madness • Folly regrets human existence • Folly praises the sciences • About the happy existence of fools • The folly and the delusion • About superstition, indulgences and saints • Conceit and flattery, existence and appearance • The foolish world theater • The folly and the theology • About monks and preachers • About kings and princes • About bishops, cardinals, popes and Priests • Wisdom and self-praise • Biblical follies • Are devout Christians fools? • Epilogue in Heaven.

With self-irony Erasmus lets his Stultitia end their “eulogy”:

“And now - I can see it - you are waiting for the epilogue. But you're really too stupid if you think I still remember what I was chatting myself, I poured out a whole sack of mixed-up words in front of you. An old word means: 'A drinking friend should be able to forget', a new one: 'A listener should be able to forget.' So God commanded, clapped, lived and drunk, you most respectable disciples of folly! "

With his work (the Inquisition had not yet been abolished) Erasmus achieved an astonishing balancing act in which he criticized the church and Christians in such a way that he could argue that it was not he, but only a fool, who could give such a speech (write such a book ). At the Council of Trent (1545) the book - like most of Erasmus's other books - was placed on the index .

German translations and edits

The first German translation was done by Sebastian Franck , it appeared in Ulm in 1534 . Several translations followed, which were then also used by Alfred Hartmann , who re-published the work in Basel in 1929. Well-known translations and edits are:

- The praise of folly. A discourse. Translated from Latin and afterword by Kurt Steinmann . Manesse-Verlag, Zurich 2002, ISBN 3-7175-1992-1 ( book review ).

- The praise of folly. Translated by Alfred Hartmann. Edited by Emil Major. Panorama, Wiesbaden 2003, ISBN 3-926642-26-2 ( book review ( memento of November 11, 2005 in the Internet Archive )).

- Praise to folly. In the translation by Lothar Schmidt. Faber and Faber, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-936618-60-7 ( Books-Google ).

- Praise to folly. Erasmus from Rotterdam. Translated from the Latin by Heinrich Hersch. Furnished and revised by Kim Landgraf. Anaconda, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-938484-98-5 .

- The praise of folly. Edited by Josef Lehmkuhl. In: Josef Lehmkuhl: Erasmus - Machiavelli. Two united against stupidity. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8260-3889-1 , pp. 131-213 ( Books-Google ).

- Praise for the folly in the Gutenberg-DE project

Quotes / sources

In Harry Mulisch's book The Discovery of Heaven , the Brons family's second-hand bookshop is called "In Praise of Folly"

- ↑ Quoted from: Beate Kellner, Jan-Dirk Müller , Peter Strohschneider (Ed.): Narrating and Episteme. Literature in the 16th century. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2011, ISBN 978-3-484-36636-7 , p. 208, note 73.

- ↑ All of the following texts based on the translation by Alfred Hartmann

- ↑ Das Theür and Artificial Buechlin Morie Encomion: that is, Ein Praise der Thorhait, scolded by Erasmo Roterodamo, to be read not less useful, then lovely, spoiled. From the Hayloszigkaitt, Eyttelkaytt, and from the certainty of all human art vn (d) weyßhait, to the end with attached. A praise of the donkey, which Heinrico Cornelio Agrippa, De vanitate etc. From the Bam desz wiszens Gutz vnd boesz dauon Adam ate the dead, and still today all people eat the dead, what he is, and how he still forbids everyone today. What against it is the bawm of life. Encomium, A Praise of the Right Divine Word, What that is, of the same Mayestät, and what kind of difference between the scriptures, utter and inner words. Everything about the tail, described by Sebastianum Francken von Wörd. Hans Varnir of Ulm, 1534.

See also

Web links

- deutschlandfunk.de , day by day , May 1, 2015, Astrid Nettling: A “praise of folly” for the renewal of faith