Luc d'Achery

Luc d'Achery (* 1609 in Saint-Quentin , † April 29, 1685 in Paris ) was an important librarian and historian of the Maurinians , who published numerous text-critical editions.

Life

Contrary to what the name suggests, the d'Achery family did not belong to the nobility. However, the family is to be assigned to the upper middle class, which derives its origin from the village of the same name Achery in northern France near Mayot . The last name was spelled both Dachery and d'Achery, the latter spelling having prevailed. There are several references to the family before the time of Luc d'Achery. For example, a d'Achery is documented as a doctor of medicine in Paris, who was seconded to the Council of Constance in 1415 . In 1544 a Nicolas d'Achery donated a stained glass window to the Abbey of Saint-Quentin-en-l'Isle. Several traders, high officials and monks of the abbey are recorded in the city of Saint-Quentin.

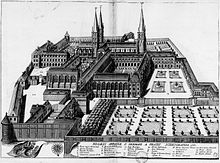

Luc d'Achery entered the Benedictine order and made his profession on October 4, 1632 at the age of 23 in the Vendôme Abbey , which was part of the Maurinian congregation. He later moved to Fleury within the congregation , where he became so seriously ill that the hope was given up that he would ever recover. In this state he was visited in 1636 by the general superior ( supérieur général ) of the Maurinians, Grégoire Tarrisse (1575-1648), and recommended him to change to the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés . Luc d'Achery followed the advice in 1637 and underwent a water cure in Paris. As a result, his suffering subsided so that he could begin work in the library of St. Germain. There he proved himself so well that in 1640, despite his health problems, he was appointed librarian.

As the new librarian, Luc d'Achery began to develop a new system according to which the entire manuscript and book inventory of the library was organized and cataloged. His way of working spread throughout the entire congregation, so that in a short time he became its leading librarian. In this position he wrote his first work, the Méthode pour la recherche des manuscrits , with which he provided his colleagues with instructions on how to use manuscripts. He then compiled a basic set of works under the title Catalog des livres pour les monastère nouveaux that every monastery library should keep or that would have to be acquired first (for a total of 527 livres at that time ) in a new library . Furthermore, with the Catalogus librorum non-nullorum quibus bibliothecae monasteriorum congregationis S. Mauri instrui potuerunt, a catalog of 456 titles was compiled for better coordination of the libraries among themselves, which in particular covered the areas of exegesis , ascetics and historical literature. With these instruments, the activities of the libraries of the entire congregation were coordinated centrally. This included the planned expansion of all libraries, the control of new acquisitions and the proper preservation of the old manuscripts.

However, the St. Germain Library particularly benefited from his activities. While only 3,600 volumes were available when he took office as librarian, that number rose to 6,300 during the lifetime of Luc d'Achery. The steadily improving library made St. Germain a center of historical scientific research in France. In part, however, this also happened at the expense of other libraries in the congregation. In 1638, with the consent of Cardinal Richelieu, around 400 of the most valuable manuscripts were permanently relocated from Corbie Abbey to St. Germain because they were considered endangered there after Corbie came under the control of Spanish troops for a few months in 1636. Quite a few manuscripts were also borrowed from the library in Fleury in preparation for a work on church fathers, only some of which were returned.

In this way, the prerequisites were created for a previously unprecedented project that provided for historical-critical works on the history of the order, on the church fathers, the lives of saints and the critical edition of important texts. Luc d'Achery prepared a research plan for the Superior General Grégoire Tarrisse, in which each monastery of the congregation should systematically record its own archive and, if possible, other archives in the neighborhood, in order to record all historical material and the documents. In particular, material about the founding circumstances of the monastery, the type of first settlement, the geographical location and further history should be recorded and evaluated. In doing so, great care was taken to ensure that the dating and the sources are as exact as possible. This project was partially implemented by the General Chapter of the Congregation in 1651 with a corresponding commission to two monks.

In addition, Luc d'Achery himself dealt with the publication of text-critical editions. In 1648, for example, Luc d'Achery published the letters of Lanfrank , the former Archbishop of Canterbury , for the first time . This became possible after Luc d'Achery came into possession of a 16th century copy based on a 12th century manuscript made in the Abbey of Le Bec , Lanfrank's home monastery. This edition was reprinted in Venice in 1745 , published again in 1844 by John Allen Giles (1808-1884), who was able to add some letters and changed the order due to another manuscript, and finally at the same time as part of the Patrologia Latina of Jacques Paul Migne . It was not until 1961 that Helen Clover created a new critical edition as part of her dissertation, which took into account a significantly larger group of manuscripts.

In the years 1655 to 1677 his thirteen- volume work Spicilegium (in German gleanings ) appeared, which included a large selection of canonical texts, chronicles, saints' lives, letters, poems and documents. The second volume, published in Paris in 1662, contains a systematic collection of canon law of southern French origin that was created around 800 and was named Dacheriana in memory of the first and so far only publisher .

The 9th volume, published in Paris in 1669, contained, among other things, excerpts from the Collectio Canonum Hibernensis , which he printed from the manuscript Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, lat. 12021 (olim Sangerman. 121). Since important parts were missing in this edition, however, Edmond Martène (1654–1739), one of Luc d'Achery's pupils, published supplements in the fourth volume of the Thesaurus novus 1717 based on the evaluation of another manuscript from the Fécamp Abbey . However, this is by no means a critical edition.

In 1664 Jean Mabillon was called as a young talent from the Abbey of Saint-Denis to St. Germain to support Luc d'Achery in order to participate in the publication of the following volumes. The sixth volume appeared in the same year. After that, however, Jean Mabillon, who would later become the most important researcher of the Maurinians, turned to the publication of the works of Bernhard von Clairvaux after Claude Chantelou (1617–1664) died in November 1664 , who had previously devoted himself to this project.

Another project was the publication of the Acta Sanctorum Ordinis Sancti Benedicti , which had already been planned by Grégoire Tarrisse. As part of this project, based on the Acta Sanctorum project of the Jesuits Heribert Rosweyde (1569–1629) and Jean Bolland, the résumés of all saints of the Benedictine order were to be presented. Luc d'Achery had been collecting material and doing preparatory work in his library in St. Germain for years. The rest of the work on it was taken over by Jean Mabillon, who further expanded his research with numerous trips to monastery libraries. The first volume of the chronologically ordered series appeared in 1668 and covered the 6th century. A reprint appeared in Venice from 1733.

The historically precise way of working led to subsequent disputes because not a few saints who had no relation to the order were sorted out from the compilation. The two authors were therefore accused of violating the honor of the order. Jean Mabillon took over the answer, in which he set out, among other things, the tasks of a historian and the duty of scientific ethos.

Works (selection)

- Beate Lanfranci Cantuariensis Archiepiscopie et Angliae Primatis, Ordinis Sancti Benedicti, opera omnia, quae reperiri potuerunt, evulgavit Domnus Lucas Dacherius Benedictus Congregationis sancti Mauri in Gallia, vitam et epistolas notis etletatisic locup, adjavit, monumentis, and observation bus . Lutetiae Parisiorum 1648.

- Spicilegium . 13 volumes, published 1655–1677.

- Acta Sanctorum Ordinis Sancti Benedicti in saeculorum classes distributa. Saeculum I, quod est ab anno Christi D ad DC, collegit Domnus Lucas d'Achery, Congregationis S. Mauri monachus, ac cum eo edidit D. Johannes Mabillon ejusdem Congregationis, qui et universum opus notis, observationibus indicibusque necessariis illustravit . Lutetiae Parisiorum 1668.

literature

- Jeannine foals: Dom Luc d'Achery (1609–1685) et les débuts de l'érudition mauriste: première partie . In: Revue Mabillon: revue internationale d'histoire et de littératures religieuses. Volume 55, year 1965, pp. 149–175.

- Jeannine foals: Dom Luc d'Achery (1609–1685) et les débuts de l'érudition mauriste: deuxième partie . In: Revue Mabillon: revue internationale d'histoire et de littératures religieuses. Volume 56, year 1966, pp. 1–30 and 73–98.

- Manfred Weitlauff : The Mauriners and their historical-critical work. In: Georg Schwaiger (ed.): Historical criticism in theology . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1980, ISBN 3-525-87492-8 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Luc d'Achery in the catalog of the German National Library

- Digitized version of the Dacheriana from the 1723 edition of the Spicilegium sive collectio veterum aliquot scriptorum (Codices Electronici Ecclesiae Coloniensis)

- Digital copies of works by Luc d'Achery in the Gallica project of the Bibliothèque Nationale

Remarks

- ↑ The information on the family was taken from the first part of the essay by J. Fohlen, p. 152.

- ↑ See page 174 in the essay by Manfred Weitlauff; The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church , edited by FL Cross and EA Livingstone , mentions 1637 as the year of his librarianship.

- ↑ See pages 202 (stay of the Spaniards in Corbie) and 194 (move to St. Germain) in the essay by Leslie Webber Jones: The Scriptorium at Corbie: I. The Library , published in the journal Speculum of the Medieval Academy of America, Volume 22 , No. 2, April 1947, pp. 191-204.

- ↑ See page 32 in Marco Mostert: The library of Fleury . Hilversum Verloren Publishers, 1989, ISBN 90-6550-210-6 .

- ↑ See page 23 in Helen Clover and Margaret Gibson: The Letters of Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury . Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1979, ISBN 0-19-822235-1 . This copy is now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France under the shelf mark lat. 13412.

- ↑ See the section The early editions on page 25 of the new edition by Helen Clover and Margaret Gibson.

- ↑ See page 178 from the essay by Manfred Weitlauff.

- ↑ page, pages 87 in Lotte Kéry: Canonical Collections of the Early Middle Ages (approx. 400-1140) . The Catholic University of America Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8132-0918-8 . In contrast, Manfred Weitlauff refers here to volume 9. However, there is apparently a mix-up with the Collectio Canonum Hibernensis. See also page 877, footnote 2, by Friedrich Maassen: History of the sources and literature of canon law in the West up to the end of the Middle Ages . First volume, Graz, 1870.

- ↑ See page 877 by Friedrich Maassen: History of the sources and the literature of canon law in the West up to the end of the Middle Ages . First volume, Graz, 1870.

- ↑ See footnote 3 on page 877 by Friedrich Maassen.

- ↑ See pages 181 and 182 in the essay by Manfred Weitlauff.

- ↑ See pages 184 and 185 in the essay by Manfred Weitlauff.

- ↑ See footnote 141 on page 187 of the article by Manfred Weitlauff.

- ↑ See pages 188 and 189 in the essay by Manfred Weitlauff.

- ↑ See footnote 101 on page 178 of the article by Manfred Weitlauff.

- ↑ See footnote 139 on page 186 of the article by Manfred Weitlauff.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Achery, Luc d ' |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Achery, Jean-Luc d ' |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Maurinian historian and librarian |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1609 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Saint-Quentin |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 29, 1685 |

| Place of death | Paris |