Nānhā

Nānhā ( Persian نانها, DMG Nānhā ) was an Indian painter in the service of the Mughal rulers Akbar and Jahāngīr . At the beginning of the 1580s he already belonged to the courtly studio, where he was not one of the top artists, but made valuable contributions both in the field of image composition and in the color design of his own and other people's designs. His last known pictures were taken around 1620. Nānhā's brother was the father of Bishandās , who is also known as a painter.

Works at Akbar's court

Nānhā contributed to many of the illustrated manuscripts created under Akbar. He has made contributions to all major thematic currents of Mughal Indian painting: illustrations for adventure stories, Persian poetry, works from the history of the dynasty and Hindu epics. During this time he worked in a wide variety of styles. While his early contributions reveal the training of Persian masters, he also made use of the new techniques from the beginning, which he was familiar with through the prints, engravings and sometimes oil paintings from Europe.

- Dārāb-nāma , ca.1580. Foll. 15r, 24r, 30r, 35r, 35v, 50v. In all illustrations, Nānhā was responsible for both the draft (pers. Ṭarḥ ) and the execution of the picture in color (pers. ʿAmal ).

- Tarīkh-i Chāndan-i Tīmūriyya , often Tīmūr-nāma for short , c. 1584. Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Public Library Patna , Ms. 551, Foll. 30r ( ʿamal ), 55v and 56r ( ṭarḥ and ʿamal ), 165v (faces only). Nānhā specialized early on in portraits, especially those of Akbar, Jahāngīr and their ancestors. He has therefore contributed to various works on the Mughal history.

- Rāmāyana , ca. 1584–89. Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum, Jaipur , MS, AG 1950. According to Verma, Nānhā was only involved in one illustration of this manuscript, in which he was responsible for the coloring. The corresponding design comes from Kānhā.

- Razm-nāma , 1582-86. Jaipur, Foll. 115-116, 119 (all colors only)

- Dīvān-i Anvarī , 1588. Harvard Art Museums , Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Object Number 1960.117.247. A barely decipherable attribution is visible under the miniature, in which several art historians believe they recognize the name Nānhā.

- Chamsa of Nizami , 1585–90. Dallas Museum of Art , K.1.2014.18; Foll. 15r ( ṭarḥ and ʿamal ), 186v (faces), 227r (faces), 230r ( ṭarḥ and ʿamal ) To design the background in fol. 15r, the painter uses the aerial perspective . The small group of houses above the text columns and the landscape at the top right in the miniature fade into the distance. This technique came to the Mughal court with European images and was already used to some extent by Basāwan in Dārāb-nāma (Fol 34r). The background design of Nānhā's illustration of the Chingīz-nāma (see below) is completely different .

- Bābur-nāma , c. 1590. Victoria and Albert Museum London, IM 276-1913 and 276A-1913: Bābur oversees the complex of the Bāgh-i Wafā 'near Kabul . On this double page, Bishndās was responsible for the draft, Nānhā for the faces of the important personalities.

- Akbar-nāma , c. 1590. Victoria and Albert Museum, IS.2: 23-1896 (faces, especially from Akbar), IS.2: 51-1896 ( ʿamal ) and IS.2: 57-1896 ( ʿamal ).

An identity of Nānhā and Kānhā alleged by J. Losty is refuted by the existence of two pictures that were made by both together, namely in the Akbar-nāma of 1590 mentioned here and in the above-mentioned Rāmāyana . In both cases the design comes from Kānhā, the coloring from Nānhā.

- Anwār-i Suhaylī , ca. 1595. Dublin , Chester Beatty Library , In. 4: King Hilar awakens from a nightmare. Detached sheet.

- Chamsa of Nizāmī , 1595. British Museum Or. 12208, Foll. 63v, 159r, 305r. Walters Art Gallery , Baltimore , W613, fol.16b. For all four illustrations, Nānhā was responsible for both the design and the coloring. This manuscript is one of the most magnificent works of Mughal painting. The fact that Nānhā is represented here with four miniatures out of a total of 42 speaks for the particular appreciation of his artistic skills.

- Tschingīz-nāma , 1596, Tehran, Golestan Palace Library, No. 2254. Foll. 54v (faces) and 70r (draft) In contrast to the chamsa in the Dallas Museum of Art (fol. 15r), the composition of the images on fol. 70r follows the Persian tradition: Nānhā indicated the spatial depth by means of rows of hills one behind the other.

- Akbar-nāma , ca. 1596–97. British Museum, London Or. 12988, fol.25a ( ṭarḥ ). According to Islamic belief, Adam was particularly tall. Abū'l Fazl adopts this idea and describes it in Akbar-nāma as 60 gaz . That is why Adam is taller than the tree next to him, and the crane in front of him appears as small as a duck.

Works for Prince Salīm / Jahāngīr

It has been suggested on various occasions that Nānhā might have left the imperial studio to follow Prince Salīm to Allahabad in 1600 . The reasons given are that in the four years up to 1604 he was involved in a conspicuously few manuscripts for Akbar, but contributed a portrait to the Salīm album, which was compiled during this period, and also an illustration for Salīms Anwār -i Suhaylī has painted. His contribution to the Salīm album could, however, have been made before 1600, like many other pictures on this album. The Anwār-i Suhaylī was only completed after the prince's accession to the throne. Nānhā's miniature therefore need not necessarily have been added before 1605. There is thus no evidence that Nānhā belonged to Salīm's studio in Allahabad. Of course, it is not ruled out either. His later works are almost exclusively portraits. All of them were subsequently framed by other artists and integrated into various albums.

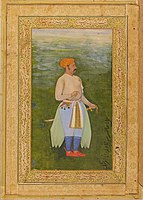

- Portrait of an Old Man, ca.1595–1600. Salīm album. Metropolitan Museum of Art 2019.159. Digitized image size 12.7 × 6.8 cm. Even if the name Nānhās appears in the caption without a long ā at the end, it can be assumed that it is precisely this painter that is meant.

- Zahid Chan. Approx. 1606. Formerly the Axel Röhm collection; Whereabouts unknown. Image size 7.4 × 15 cm. Inscription: Work of Nānhā. Portrait of Zahid Chan. It is probably the son of Sādiq Chān from Herat. After the death of his father, he came to the Mughal court and was awarded the title of Chān by Akbar shortly before Akbar's death. The latest news from him comes from an entry in the Jahāngīr-nāma in February 1607.

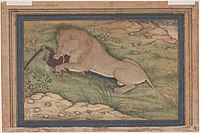

Lion attacks

Hunting encounters with lions and attacks by lions were apparently a preferred subject of the painter. However, we only have two pictures which are verifiably labeled with Nānhā's name.

- Anwār-i Suhaylī , approx. 1604-10. British Library Add. 18579, fol 280v.

A lion kills a farmer's wife who ran away with a prince.

- A lion attacks a hunter , approx. 1605. Free Library of Philadelphia, Lewis M 36. Image size 19 × 29 cm. Painted on silk.

According to SP Verma, there are two other works by Nānhā in the Baroda State Museum and Picture Gallery, on which Jahāngīr or Prince Churram kills a lion and both of which are labeled "ʿamal-i Nānhā". Neither of them is published. Milo C. Beach and SP Verma also ascribe to Nānhā a picture not marked with his name from around 1615 in the Indian Museum Kolkata, on which Jahāngīr's shot in the eye of a lioness is recorded.

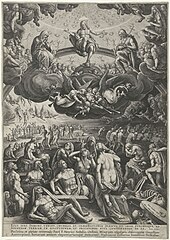

Copy of an engraving from Flanders

The Last Judgment , around 1605, in a Chamsa by Mir ʿAli Schir Nawāʾi . Resurrection scene added later on fol.5b. Royal Library Windsor Castle Library, RCIN 1005032.d. Work of Nānhā and Manōhar. Image size 22.4 × 14.8 cm. The text in Chagatai was copied in Herat as early as 1492 , but the open spaces for the illustrations remained almost all empty. After a checkered history, the manuscript came to the Mughal court, where Nānhā and his colleague Manōhar added this scene of the Last Judgment . The artists took the model from a copper engraving by Adriaen Collaert, which was made in Flanders in the late 16th century and which very likely found its way to Akbar's court with Jesuit embassies . When making copies, the painters did not stick strictly to their original, but instead set their own accents. This includes, above all, the reproduction in color, with the blessed being marked by light colors and the damned by shades of gray. All people were shown a little larger, but their number was reduced. In their version, the Mughal artists have considerably softened the strong emphasis on the individual muscle parts in the copperplate, thereby giving the figures a softer shape. The resurrection scene has no relation to the surrounding text. However, an illustrated passage on folio 35v of the same manuscript may have influenced the selection. There is a fictional discussion between Fachr ad-Dīn ar-Rāzī and Shah Muhammad of Khorezmia about the Day of Judgment.

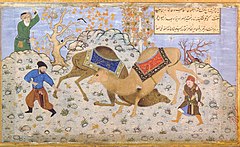

Copy of Behzād's “Camel Fight”

Camel fight , approx. 1608. Gulschan album , Tehran, Golestan Palace Library No. 1663. Image size 25.5 × 15.6 cm. For the Mughals, who were themselves a branch of the Timurids, books, pictures and other works of art from their home country had a high ideal value. They were regarded as symbols of Timurid greatness, which, as Lentz and Lowry write, “reminded them of their sublime ancestry and history of rule.” Behzād in particular was regarded by the Mughals as the pinnacle of all painting, by which Indian painters also had to be measured. A picture called a “camel fight”, in the text field of which the “poor and unfortunate Behzād” reveals himself as a painter, was copied by Mīr Sayyid ʿAlī under Akbar . Another copy was to be made by Nānhā on behalf of Jahāngīr. The Mughal ruler personally inscribed the text field: “God is great. After seeing this work by Master Behzād, the painter Nānhā copied it according to my orders. Written by Jahāngīr, son of Akbar Padishāh Ghāzī 1608/09. “The copy was included in the Gulschan album and forms a double page with the original.

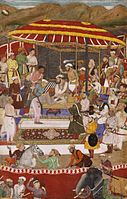

Nānhā in Mewar

Akbar had already tried in vain to subdue Mewar . Jahāngīr continued the efforts and on December 16, 1613 sent his son Prince Churram , the later Shah Jahān, to conquer the land of Rana Amar Singh Sisodia . A good year later, Muhammad Beg brought the news that the Rana had submitted to the Mughals in an official ceremony in Gogunda on February 6, 1615. Nānhā either accompanied the prince on the campaign or did not hurry to Gogunda until the beginning of February 1615 to capture the historic event of the surrender in a picture. In addition, he portrayed some of the most important figures associated with the Mewar campaign, probably around the same time.

- Rana Amar Singh of Mewar submits to Prince Churram, approx. 1615-18. Victoria and Albert Museum, IS 185-1984. Image size 31.3 × 20.1 cm. The sheet most likely belonged to an illustrated Jahāngīr-nāma . The custodian , who can be seen in the lower left of the picture on a man's white robe, refers to the corresponding passage in Jahāngīr's memoirs. On the right side of the picture the painter has depicted himself in the midst of the courtiers at work. The important personalities are marked with their names in small letters. He noted his own name on his sketch sheet.

- Maharajah Bhīm Kunwar, approx. 1615-19. Verso album page from the Shah Jahan album . Metropolitan Museum of Art, 55.121.10.2v. Page size 38.7 × 25.6 cm. Image size 16.4 × 9.7 cm. On the left edge of the picture is written in Jahāngīr's handwriting: “Work of Nānhā. Picture of Bhīm Kunwar, son of Rānā Amar Singh, who has received the title of Maharajah. ”Under the portrait, on the floral inner border, Shah Jahān also left a note:“ Our best servants in our time as princes were Maharajah Bhīm and Raja Bikramajit and both of them have sided with us. ”Bhīm Kunwar has served the Mughals since the subjugation of Mewar. On the orders of Jahāngīr he was assigned to Shah Jahān, to whom he remained loyal even during his rebellion against his father. He died in 1624 fighting against the imperial troops.

- Sūradsch Mal. Indian Museum, Calcutta. This picture also bears an inscription that Verma classifies as an autograph of Jahāngīr: Work by Nānhā. Image of Sūradsch Mal, son of Rānā Amar Singh.

- Muhammad Beg Zulfiqār Chān. Approx. 1615. Page from the Minto album. Victoria and Albert Museum, IM.24-1925. Image size 15.8 × 9.7 cm. The inscription on the left edge of the picture, “Portrait of Zulfiqār Khān. Work of Nānhā ”, most likely comes from Jahāngīr. Shāh Jahān added the following note on the margin below the picture: “He was one of my good servants. He was unique in archery and in the shooting of gaz arrows. ”Muhammad Beg was the messenger who informed Jahāngir of the news of the submission of Rana Amar Singh. In return, the Mughal ruler made him valuable gifts and awarded him the title of Zulfiqār Chān.

- Sayf Chān Bārha. Approx. 1615. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 55.121.10.4v. Page from the Shāh Jahān album . Page size 38.3 × 26.2 cm. Image size approx. 6.5 × 14 cm. Inscription from Jahāngīr: “Portrait of Sayyid Sayf Chān Bārha. Work of Nānhā. ”Sayf Chān was actually called ʿAlī Asghar Bārha. He was a close confidante of Jahāngīr, who had given him the title Sayf Chān in 1606 because of his zeal for service and his bravery. He was involved in a leading position in the campaign against Rana Amar Singh. In 1616 he died of cholera.

Late work

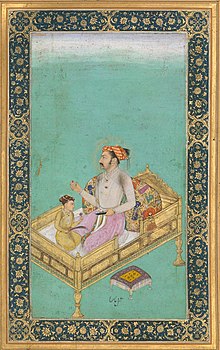

- Shāh Jahān with his son Dārā Schukoh . Page from the Shah Jahan album. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Accession Number: 55.121.10.36v. Page size 38.9 × 26.2 cm. From the age of Shah Dschahan (born 1592) and that of his son Dārā Schukoh (born March 20, 1615), an origin date of around 1620 can be derived. The inscription of Jahāngīr reads “Work of Nānhā”.

- Conversation between two sheikhs. Approx. 1620. Petersburg Album, fol. 46r. Size: 9 × 9.7 cm, expanded later. On the knee of the right man is written: Portrait of Sheikh Bāyazīd. The clothing of the left person reads: Portrait of Sheikh Jalāl. Neither of the two portrayed can be assigned to a historical personality with certainty. Nānhā's signature is on a light bowl in the center of the foreground.

- Hindu ascetic under a tree with adorant. Victoria and Albert Museum, IS.229-1951. Small ink drawing in a margin with gold leaf. Overall size 26.5 × 16.5 cm. The drawing alone has a height of 6.5 cm and a width of 6.7 cm. According to the Victoria and Albert Museum, the picture was later attributed to Nānhā. A period from 1620 to 1650 is given as the date of origin.

literature

- Abu'l Fazl: The History of Akbar , vol. 1st ed. and Transl. by Wheeler M. Thackston. Murty Classical Library of India. Harvard University Press, Cambridge Mass. 2015. ISBN 978-0-674-42775-4 .

- Adamova, Adel, and JM Rogers. “The Iconography of 'A Camel Fight.'” Muqarnas 21 (2004): 1-14. ISBN 978-90-04-13964-0 .

- Beach, Milo Cleveland: The Grand Mogul. Imperial Painting in India 1600–1660. Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, 1978. pp. 147-150. ISBN 0-931102-01-4 .

- Beach, Milo Cleveland: The Imperial Image. Paintings for the Mughal Court. Freer Gallery of Art, Washington DC 1981. ISBN 0-934686-37-8 .

- Binyon, Laurence, Wilkinson, JVS and Gray, Basil: Persian Miniature Painting. Dover Publications, New York 1971. (Repr. 1933)

- Brend, Barbara: The Emperor Akbar's Khamsa of Niẓāmī. The British Library, London 1995.

- Jahāngīr, Nūr ud-Dīn Muḥammad: Jahāngīr-nāma. Tūzuk-i Jahāngīrī. Ed. Muḥammad Hashim. o. O. (Tehran) 1359 HŠ / 1980.

- The Jahangirnama. Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Translated, edited and annotated by Wheeler M. Thackston. Oxford University Press, New York 1999. ISBN 0195127188 .

- Godard, André and Gray, Basil: Iran. Persian miniatures. Imperial Library. Graphic Society, New York 1956. Plate XXX.

- Habsburg, Francesca von (Ed.): The St. Petersburg Muraqqaʿ. Album of Indian and Persian Miniatures from the 16th through the 18th Century and Specimens of Persian Calligraphy by ʿImād al-Ḥasanī. Leonardo Arte, Milano 1996. ISBN 88-7813-607-7 .

- Hannam, Emily: Eastern Encounters. Four Centuries of Paintings and Manuscripts from the Indian Subcontinent. Royal Collection Trust, London 2018. ISBN 9781909741454 .

- Leach, Linda York: Mughal and other Indian paintings from the Chester Beatty Library. 2 vols. Scorpion Cavendish, London 1995. ISBN 1-900269-02-3 .

- Lentz, Thomas W. and Lowry, Glenn D .: Timur and the Princely Vision. Persian Art and Culture in the Fifteenth Century. Museum Associates, Los Angeles County Museum of Art 1989. ISBN 0-87474-706-6 .

- Losty, Jeremiah P .: The Art of the Book in India. London, The British Library 1982. No. 59.

- Samsam-ud-daula Shāh Nawāz Khān and Abdul Hay: The Maāthir-ul-umara. 2 volumes. Translated by H. Beveridge. Low Price Publications, Delhi 1999. ISBN 81-7536-159-X .

- Seyller, John: "Nanha", in: Jonathan M. Bloom and Sheila S. Blair (eds.): The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press, New York 2009. Vol. 3, pp. 45f. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1 . The author's name is only mentioned in the online version. Digitized .

- Sharma, GN: Rajasthan through the Ages. Rajasthan State Archives, Bikaner 1990.

- Simsar, Muhammad Hasan, translated and edited by Karim Imami: Golestan Palace Library: a portfolio of miniature paintings and calligraphy. Zarrin & Simin Books, Tehran 2000. ISBN 9649211322 .

- Soucek, Priscilla P .: Persian Artists in Mughal India: Influences and Transformations , Muqarnas 4 (1987) 166-181.

- Stronge, Susan: Painting for the Mughal Emperor. The Art of the Book 1560-1660. V&A Publications, London 2002. ISBN 1-85177-358-4 .

- Titley, Norah M .: Miniatures from Persian Manuscripts. A Catalog and Subject Index of Paintings from Persia, India and Turkey in the British Library and the British Museum. British Museum Publications Limited, London 1977. ISBN 0714106593 .

- Verma, Som Prakash: Mughal Painters and their Works. A biographical survey and comprehensive catalog. Oxford University Press, Delhi, Bombay u. a. 1994. ISBN 0-19-562316-9 .

- Welch, Stuart Cary: Mughal and Deccani Miniature Painting from a Private Collection , Ars Orientalis 5 (1963) 221-233.

- Welch, Stuart Cary and Schimmel, Annemarie: Anvari's Divan: A Pocket Book for Akbar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983. ISBN 0-87099-331-3 .

- Welch, Stuart Cary; Schimmel, Annemarie; Swietochowski, Marie L. and Thackston, Wheeler M .: The Emperors' Album. Images of Mughal India. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harry N. Abrams, New York 1987. ISBN 0-8109-0886-7 .

- Wright, Elaine: Muraqqaʿ. Imperial Mughal Albums from the Chester Beatty Library. Art Services International, Alexandria (Virginia) 2008. ISBN 0-88397-154-2 .

supporting documents

- ↑ See the inscription of a marginal illustration on Jahāngīr's Gulschan album , Verma 1994, p. 128.

- ↑ Beach 1981, pp. 218-220.

- ↑ Verma 1994, p. 314, no. 2. No illustration has been published for this.

- ^ Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II City Palace Museum, Jaipur. See Beach 1981, pp. 215-217. None of these miniatures has yet been published.

- ↑ Welch 1983, p. 105.Seyller , Nānhā , p. 46.

- ↑ digitized version

- ↑ digitized version

- ↑ Losty 1982, No. 59.Seyller , Nānhā , III / 46.

- ↑ Akbar-nāma Victoria and Albert Museum, IS 2: 57-1896.

- ↑ Leach 1995, Volume 1, p. 104, illustration p. 102, catalog no. 1.188, image no. 151

- ↑ See Brend 1995.

- ↑ Beach 1981, pp. 223-226. Colored illustration in Godard and Gray 1956, plate XXX.

- ↑ Abu'l Fazl, History of Akbar , Vol. 1, pp. 178-179.

- ^ Wright 2008, p. 61.

- ↑ Beach 1978, p. 149, here a b / w illustration. Jahangirnama , Thackston, p. 65. Ma'athir-ul-umara Vol. 2, p. 1020.

- ↑ digitized version

- ↑ Beach 1978, p. 149, No. 50 dated around 1615.

- ↑ digitized version

- ↑ Verma 1994, pp. 318f., No. 45 and 46.

- ↑ Verma 1994, p. 319, no. 49; Beach 1978, p. 150.

- ↑ digitized version

- ↑ The Last Judgment. Engraving by Adriaen Collaert after Jan van der Straet, 1570 - 1618. Rijks Museum Amsterdam RP-P-1982-305. Digitized

- ↑ Hannam, 2018, pp. 98-103.

- ↑ Hannam 2018, p. 101.

- ↑ Binyon et al. a. 1971, pp. 130-131.

- ↑ Lentz and Lowry 1989, p. 320.Soucek 1987, p. 166.

- ↑ Adamova 2004, p. 2, points out that this picture is very likely just a faulty copy of an older original by Behzād.

- ↑ Allāhu Akbar. In kār-i ustād Bihzād-rā dida Nānhā-i muṣawwir kār karda ḥasb ul-ḥukum-i man. Ḥarrarahu Ǧahāngīr ibn Akbar Pādišāh Ġāzī, sana 1017.

- ↑ Semsar 2000, pp. 260f.

- ↑ Jahangir-nama , Thackston, p. 165. Sharma, Rajasthan , p. 118.

- ↑ See page 156 in the edition of Jahāngīr-nāma .

- ↑ ʿamal-i Nānhā, šabih-i Bhīm Kunwar walad-i Rānā Amar Sing ki khitāb-i mahārāǧagī yāfta bud.

- ↑ Bihtarin naukarān-i mā dar ayyām-i pādšāhzādagī Mahārāǧa Bhīm wa Rāǧa Bikramāǧīt budand wa har dū ba-kār-i mā āmadand.

- ↑ Jahangirnama , Thackston, p. 426. Welch 1987, pp. 148-149.

- ↑ Verma 1994, p. 317, no.31 . Maāthir-ul-umara , Vol. 2, p. 880.

- ↑ Stronge 2002, pp. 144-145.

- ↑ Jahangirnama , Thackston, p. 165.

- ↑ digitized version

- ↑ Jahangirnama , Thackston, pp. 35 and 194. Ma'athir-ul-umarā II: 692-693. Which u. a. Emperors' Album, p. 122, No. 21.

- ↑ digitized version

- ↑ Welch 1987, pp. 194-195.

- ^ Gauvin Bailey in F. von Habsburg, St. Petersburg Muraqqaʿ , plate 61, p. 71.

- ↑ digitized version

Web links

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Nānhā |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Nanha |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Indian miniature painter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 16th Century |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 1600 |