Namamugi incident

The Namamugi Incident ( Japanese 生 麦 事件 , Namamugi jiken ) was an attack by samurai on British foreigners in Japan on September 14, 1862. It is also known under the terms Kanagawa Incident or Richardson Affair . The result of this incident was that Kagoshima was shelled by British ships. In Japanese historiography, this bombardment is considered a war between the Daimyat Satsuma and Great Britain , which is why it is also known there as the British-Satsumian War .

At the site of the incident there is now a memorial ( 35 ° 29 ′ 28.73 ″ N , 139 ° 39 ′ 48.69 ″ E, ).

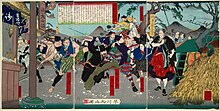

Course of the incident

Four British citizens, namely the merchant Charles Lennox Richardson from Shanghai , two other men and a woman named Borrodaile, traveled on the Tōkaidō road towards the Heiken-ji temple in what is now Kawasaki . As they passed through the village Namamugi in district Tachibana in the Musashi Province (now Namamugi, Tsurumi-ku , Yokohama , Kanagawa Prefecture ) came, they encountered the daimyo of Satsuma, Shimazu Hisamitsu , with his entourage of about 1000 people. Out of ignorance and arrogance, the British neglected to dismount their horses in deference to the daimyo, as was prescribed in Japan at the time. Richardson, who was known in Shanghai for his arrogance towards Asians (and for his brutality towards a coolie working for him ) also ignored the demands of the guards of the daimyo . Richardson used to say that he already knew how to deal with "Orientals". Thereupon Richardson and his companions were attacked with the sword by the samurai of the escort in order to punish them for the disregard of the daimyo. Richardson was killed and the other two men seriously injured.

British response

When the incident became known to foreigners residing in the Kannai neighborhood of Yokohama, they feared that something similar might happen to them. During this time there were several attacks by men from the Daimyat Chōshū ( Nagato province ) on foreigners in Yokohama. There were two nightly attacks on the British Legation building in Yokohama. In addition, foreign ships trying to pass the Shimonoseki Strait were shot at by coastal batteries near Nagato . Many traders appealed to their governments to force the Japanese to observe trade agreements and, if necessary, to retaliate.

The British dispatched a flotilla of twelve ships under the command of Admiral Augustus Leopold Kuper, which arrived off Yokohama in February 1863. On April 6, 1863, the British demanded by the Tokugawa shogunate- atonement payment of 100,000 pounds sterling . They also demanded that the Shogun Tokugawa Iemochi convict the murderers and execute them in the presence of British officers. The Japanese were outraged that the British delivered the verdict with the demand for the trial. In addition, the Shogunate was unable to prevail against the daimyo of Satsuma. Because the daimyates Satsuma and Chōshū were supported by a movement opposing the shōgunate, whose motto was: Sonnō jōi ("Worship the emperor, get away with the barbarians"). So the Japanese government finally paid the required atonement.

Bombardment of Kagoshima

The second British demand remained unfulfilled: the Shimazu- Daimyō of Satsuma did not allow the murderers to be arrested. After the expiry of an ultimatum, the British retaliated on August 15, 1863 by bombarding the port of their capital, Kagoshima, from their ships. Fire broke out in the city, 500 houses burned down and five residents were killed. On the British side, 13 sailors died, most of them on the HMS Euryalus , which was hit directly by the Kagoshima coastal batteries. Three Japanese steam boats were sunk.

This was the first time Britain had applied its gunboat policy to Japan. Due to the damage suffered, the British ships withdrew to Yokohama after the bombardment of Kagoshima. In December 1863, the British received an additional £ 25,000 to compensate, as it were, for not having the murderers delivered to them.

aftermath

The Namamugi incident and the Kagoshima bombardment sparked extensive debates in the lower house of the British Parliament . John Bright attacked the Palmerston administration for this. But the British merchants, the Foreign Office and the Admiralty remained determined to gain access to Japan. On September 5, 1864, an Allied fleet, whose ships were provided by the French , British, Americans and Dutch , opened the Shimonoseki Strait by destroying the Japanese coastal batteries .

literature

- Morinosuke Kajima: History of Japanese Foreign Relations . Vol. 1: From the opening of the state to the Meiji restoration , Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 1976, ISBN 3-515-02554-5 .

- William G. Beasley, Marius B. Jansen, John Whitney Hall, Madoka Kanai, Denis Twitchett (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Japan , Vol. 5: The Nineteenth Century . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989, ISBN 0-521-22356-3 , Chapter 4: The foreign threat and the opening of the ports .

- Ernest Satow: A Diplomat in Japan . Routledge Shorton , London 2000, ISBN 4-925080-28-8 , chapter 5.

- Ian C. Ruxton: The Namamugi incident: An investigation of the incident and its repercussions . In: Studies in Comparative Culture, Vol. 27 (1994), pp. 107-121.

Web link

- Daylan Cosco: The Namamugi Incident. In: Yokohama echo. March 2003, archived from the original on February 8, 2006 ; accessed on January 10, 2015 .

Footnotes

- ↑ Olive Checkland: Britain's encounter with Meiji Japan, 1868–1912 . Macmillan, Houndmills 1989, ISBN 0-333-48346-4 , pp. 18-19.

- ^ Ian C. Ruxton: The Namamugi incident: An investigation of the incident and its repercussions . In: Studies in Comparative Culture, Vol. 27 (1994), pp. 107–121, here p. 115.

- ^ Ian C. Ruxton: The Namamugi incident: An investigation of the incident and its repercussions . In: Studies in Comparative Culture , Vol. 27 (1994), pp. 107–121, here p. 107 and p. 114–117.

- ^ Richard Storry: A history of modern Japan . Penguin, Harmondsworth, 9th ed. 1972, pp. 97-98.

- ^ A b Richard Storry: A history of modern Japan . Penguin, Harmondsworth, 9th ed. 1972, p. 98.

- ^ Ian C. Ruxton: The Namamugi incident: An investigation of the incident and its repercussions . In: Studies in Comparative Culture , Vol. 27 (1994), pp. 107–121, here p. 107.