Neostalinism

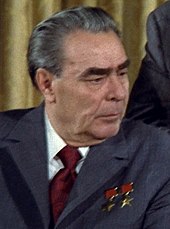

Neostalinism is a term for totalitarian real socialist forms of government which, after the death of Josef Stalin , continued or revived his politics ( Stalinism ), mostly in a modified, less extreme form. The use of the term is not entirely uniform here. Occasionally it is used for almost all totalitarian socialist governments after the death of Stalin, but mostly the time of the Nikita Khrushchev government is excluded because of the de-Stalinization it began in 1956 and the associated thaw period . In this case, neo-Stalinism refers in particular to the political system of the Soviet Union and its satellite states, which was shaped by Leonid Brezhnev from 1964 to 1985. In the official parlance of the socialist governments concerned, this period of neo-Stalinism was referred to as "normalization".

Neo-Stalinism in the Soviet Union

After the unexpected fall of Nikita Khrushchev by structural conservative forces in 1964, his former companion Leonid Brezhnev took over the leadership of the Soviet Union together with Alexei Kosygin . At first it seemed as if the reforms introduced by Khrushchev would be continued, and the principle of de-Stalinization was initially adhered to. From the spring of 1965, however, there were increasing signs that the dogmatic-conservative forces were advancing. A first sign of a change of course was the attempt to rehabilitate Stalin again and make him appear positive. For example, Brezhnev highlighted Stalin for the first time on the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of the victory in World War II . Stalin's crimes were hardly mentioned in the articles about the Soviet State Security Service either.

The change of course in the massive restriction of freedom of expression became even clearer. Among other things, the two regime-critical writers Andrei Sinjawski and Juli Daniel were arrested and a house search carried out on Alexander Solzhenitsyn . At the end of January 1966, the central party newspaper Pravda wrote that a number of mistakes had been made in the course of de-Stalinization, the exposure of the personality cult had gone too far and the term "period of the personality cult" was generally un-Marxist and wrong. It has also been claimed that the struggle against the Stalinist personality cult led to nihilism and cosmopolitanism as well as other anti-Leninist ideas and movements.

At the 23rd party congress of the CPSU in 1966, Stalin was not officially rehabilitated. Exceptionally sharp attacks against reform-minded writers (who were still able to write freely under Khrushchev), the renaming of the party presidium to the Politburo and the first secretary to general secretary (previously only Stalin had held this title) and the abolition of the rotation system introduced by Khrushchev showed that the harder one Course had now also been officially sanctioned. Domestically, Khrushchev's doctrine was pushed back by the "peaceful socialist transformation" and no longer publicly mentioned. In foreign policy, Khrushchev's principle of “ peaceful coexistence ” was now seen as part of the struggle against imperialism , the main goal now being to secure favorable international conditions for the construction of socialism and communism . The Brezhnev Doctrine later stipulated that the USSR would intervene militarily in other real socialist states if socialism were threatened there (as in the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 and the military intervention in Afghanistan in 1979).

Instead of distancing themselves from Stalinism and de-Stalinization reforms, the new leadership was interested in consolidating its own power and authority and therefore tied in with the Stalinist tradition. Censorship was tightened, the arrests and trials of dissidents increased, and prison and working conditions in the labor camps deteriorated. The Ministry of the Interior , disbanded by Khrushchev in 1960, was re-established with the infamous acronym MWD , and new penalties for “knowingly spreading lies” denigrating the Soviet state and order were introduced. The criticism of Stalin was replaced by the renewed glorification of his "military exploits" during the " Great Patriotic War "; at the same time the youth were indoctrinated by a military-patriotic upbringing.

The era of Neo-Stalinism only ended with the reforms of Mikhail Gorbachev , who criticized Stalin's crimes again and ushered in a departure from the Stalinist tradition. Gorbachev describes the political system of the Brezhnev era as "a Stalinism without repression, but with absolute control of everything and everyone". However, there were already approaches in this direction with the moderately reformist Yuri Andropov , but these could not be implemented due to Andropov's reign of only 14 months (he was followed by the hardliner Konstantin Chernenko ).

Neo-Stalinism in Romania

Some scholars such as Anton Sterbling and Mariana Hausleitner also interpret Nicolae Ceaușescu's dictatorship in Romania as neo-Stalinist. Sterbling differentiates between Stalinism, which led to a complete Sovietization of the country in the 1940s and 1950s, and the so-called "national communist Neo-Stalinism" , which began with the seizure of power by Ceausescu. Stalinism and national communist neostalinism therefore not only have essential similarities, but also a profound structural continuity. However, essential differences are also recognizable, so the focus of the ideology of the Stalinist dictatorship in Romania was initially communist egalitarianism and the “class struggle”, which was directed against the “exploiters” and “class enemies”, as well as revolutionary “internationalism” and the inviolable Friendship and gratitude towards the Soviet Union and its great leader Stalin; With the de-Stalinization, however, the distance to the Soviet Union in Romania gradually grew, which increased even further when the Warsaw Pact troops marched into Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague Spring in 1968. In the re-ideologization, which began in the early 1970s, extreme Romanian nationalism and the personality cult around the “greatest leader and son of his people” took on a central ideological role, but without completely renouncing social revolutionary rhetoric.

Another reason for the difference was the situation of the ethnic minorities . During the Stalinism of the 1950s and early 1960s, large parts of the German and Hungarian minorities were particularly badly affected by collective and individual repression, persecution and discrimination measures, while other ethnic minorities, for example the Slavs (such as Russians, Ukrainians, southern Slavs), Back then, at least temporarily, were clearly preferred and promoted. During the time of the neo-Stalinist Ceaușescu dictatorship, however, almost all ethnic minorities (Germans, Slavs and Hungarians) were treated similarly; that is, they were almost without exception exposed to comparable processes of discrimination and compulsions to assimilate, persecution and blackmail.

Political catchphrase

The term neo-Stalinism is also occasionally used as a political catchphrase , in order to show links to Stalinism in terms of content, according to the opinion of the respective authors. For example, Vladimir Putin's political system of “ directed democracy ” - Putinism - is interpreted as neo-Stalinist. The historian Christoph Jünke notes increasingly self-confidently presented attempts to update essential theorems of the old Stalinist worldview and to justify historical Stalinism more or less openly, and describes them as neo-Stalinist.

criticism

Some scholars, such as the German sociologist Werner Hofmann , reject or do not use the term as a political characterization for the Brezhnev era, because in his opinion the de-Stalinization did not end with the overthrow of Khrushchev, but was continued in some areas under other aspects be.

literature

- Robert V. Daniels: The End of the Communist Revolution. Routledge, London et al. 1993, ISBN 0-415-06150-4 , pp. 34, 72-74, ( limited online version (Google Books) ).

- Thomas Kunze : Nicolae Ceaușescu. A biography. Ch. Links, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-86153-211-5 , pp. 187-211, ( excerpt in the Google book search).

- Wolfgang Leonhard : The triple division of Marxism. Origin and development of Soviet Marxism, Maoism and reform communism. Econ-Verlag, Düsseldorf / Vienna 1970, pp. 251-256.

- Jozef Žatkuliak: Slovakia in the Period of "Normalization" and Expectation of Changes (1969–1989). (PDF; 356 kB) In: Sociológia. Slovak Sociological Review. Vol. 30, No. 3, 1998, ISSN 0049-1225 , pp. 251-268, (Neo-Stalinism in Slovakia).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Peter Davies, Derek Lynch: The Routledge Companion to Fascism and the Far Right. Routledge, London et al. 2002, ISBN 0-415-21494-7 , p. 345 .

- ↑ The Russian historian Roi Alexandrovich Medvedev described neo-Stalinism in the Soviet Union as follows: It is not so much a really positive view of Stalin that is characteristic of the neo-Stalinists, but the desire to have a strong and strict leadership in the party and government again . They want the Stalin government's administrative terrorism to return, but avoiding its worst excesses. The neo-Stalinists are fighting not to expand socialist democracy, but to reduce it. They stand for stricter censorship and the cleansing of the social sciences, literature and art and the strengthening of bureaucratic centralism in all areas of public life. Translated and quoted from: Ferdinand Joseph Maria Feldbrugge: Samizdat and Political Dissent in the Soviet Union. Sijthoff, Leyden 1975, ISBN 90-286-0175-9 , p. 30 f.

- ↑ Hannah Arendt states in her book Elements and Origins of Total Rule after Stalin's death a dismantling of total rule and advocates the thesis that since then the Soviet Union can no longer be called totalitarian in the strict sense. Hannah Arendt, Elements and Origins of Total Domination. Anti-Semitism, imperialism, total domination. Piper, Munich / Zurich, 5th edition 1996, ISBN 3-492-21032-5 , pp. 632, 650.

- ↑ Alexander Dubček : "The beginning of the Brezhnev government heralded the beginning of neo-Stalinism, and the measures against Czechoslovakia of 1968 were the last consolidation step of the neo-Stalinist forces in the Soviet Union, Poland, Hungary and other countries." In: Jaromír Navrátil (ed .): The Prague Spring 1968. A National Security Archive documents reader. Central European University Press, Budapest 1998, ISBN 963-9116-15-7 , pp. 300–307, ( online copy of the interview with Dubček (English translation) ( memento of the original of March 14, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info : The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note. ).

- ↑ Robert Vincent Daniels: "Between 1985 and 1989 Gorbachev was looking for an abolition of neo-Stalinism ..." and "... the movement of intellectual dissidents whose independent spirits developed on a large scale during the thaw and which did not develop in subsequent neo-Stalinism either completely suppressed. ” In: Robert V. Daniels: The End of the Communist Revolution. 1993, pp. 34 and 72.

- ↑ Jozef Žatkuliak: Slovakia in the Period of "Normalization" and Expectation of Changes (1969–1989) (PDF; 356 kB). In: Sociológia. Slovak Sociological Review. Vol. 30, No. 3, 1998, pp. 251-268.

- ^ Quote from Gorbachev in: 50 years ago. Attack on father figure Stalin ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . In: Stuttgarter Zeitung , February 24, 2006 (DPA article).

- ^ Mariana Hausleitner : Stalinism and Neostalinism in Romania. In: Southeast Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries. Foreign ways - own ways (= Berlin yearbook for Eastern European history. Vol. 2). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-05-002590-5 , pp. 87-102.

- ↑ Cf. Anton Sterbling: Stalinism in the Heads ( Memento from August 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ). Orbis Linguarum, Vol. 27, Wroclaw 2004.

- ↑ Example: Lena Kornyeyeva: Putin's Empire: Neostalinism at the request of the people . aschenbeck Verlag 2009, ISBN 978-3-939401-98-8 .

- ↑ A bit of democracy, a lot of oligarchy. Luciano Canfora, European Democracy and the German Left , Christoph Jünke, IABLIS, 2007

- ↑ Off to the last stand? On the criticism of Domenico Losurdos Neostalinismus , Christoph Jünke, UTOPIEkreativ, August 1, 2000, at Linksnet

- ↑ Cf. Werner Hofmann : What is Stalinism? (= Thistle booklets 5). Distel-Verlag, Heilbronn 1984, ISBN 3-923208-06-5 .