Nuclear winter

Nuclear winter refers to the darkening and cooling of the earth's atmosphere as a result of a large number of nuclear weapon explosions .

Scenarios

Research on the nuclear winter describes several independent effects which, according to the authors, can lead to a nuclear winter after a large-scale use of nuclear weapons :

- The force of the explosions hurled a large amount of dust into the atmosphere

- Large wildfires are ignited by the development of heat and produce thick smoke

- Major fires in the cities affected burn large amounts of oil and plastics, which produce an even denser smoke than forest fires

The enormous heat of these large-scale fires would carry smoke, soot and dust very high into the atmosphere, so that it would take weeks or months, depending on the extent of the destruction, before they sank again or washed out. During this time, a large part of the incident sunlight would be absorbed by them, so that the surface temperature would drop by around 11 to 22 K ( Kelvin ). The cold, on the one hand, and the resulting crop failures with subsequent famine, on the other, are responsible for a much higher number of victims than the bombs themselves.

The first model calculations for the concept of the nuclear winter suffered from the then limited computer capacities. Only a small part of the atmosphere was modeled, and the influence of oceans on the climate could not be taken into account. New model calculations with the reduced arsenal after the end of the Cold War show that the effects were rather underestimated at the time. Using the NASA - modèle that also for the simulation of, global warming is used, and other current climate issues, Robock and colleagues were able to show that the average temperature on the surface of the earth , depending on the extent of nuclear breakdown at 6 - 8 would drop K; Large areas in North America and Eurasia, including all agriculturally relevant areas there, would even cool by more than 20 or 30 K respectively. This effect lasted for the entire simulation period of ten years.

A model calculation from 2014, which represented a limited nuclear war between India and Pakistan with the use of fifty 15 kt warheads, showed a reduction in the vegetation period by 10 to 40 days due to cooler temperatures and a reduction in the ozone layer by a third to a half.

History of science

Since no nuclear weapons with sufficient explosive power have been used so far, no direct observations of the phenomenon are available. In 1974, John Hampson pointed out the possibility of damage to the ozone layer by nuclear weapons in the science journal Nature . The author calculated that the ozone layer would be damaged by nitro compounds for several years. As a result, more harmful UV radiation would hit the planet's surface. In 1982 Paul J. Crutzen and John W. Birks published a model calculation for the climate after an extensive nuclear exchange in a journal of the Swedish Academy of Sciences. They concluded that cooling for a long time after the explosions was likely. Food production would collapse in the northern hemisphere. The authors assumed nitrous gases and oxygen radicals from fires after the detonations were the main causes .

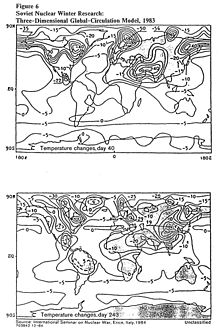

In 1983, Turco et al . Drew attention to the direct and indirect damage caused by nuclear weapon explosions in a model calculation study in the journal Science . The study was referred to as TTAPS study after the initials of their authors and coined the term nuclear winter (Engl. Nuclear winter ). She presented a scenario with several weeks of cooling to −15 to −25 degrees Celsius when using several thousand megatons. She also postulated that from 100 megatons above large cities, a noticeable drop in temperature to a few degrees above freezing point could occur. The authors calculated forest and construction fires as well as the amount of dust caused directly by air and soil explosions. However, they also noted that many parameters were still unexplored and not considered. In the same year, a Soviet research group headed by Vladimir W. Alexandrow came to similar results as the TTAPS study on the basis of their own model.

Six American scientists postulated in a study published in 1984 that the use of nuclear weapons with a total explosive force of 5000 megatons would inevitably darken the earth.

In 1990 the TTAPS team presented a follow-up study which contained a detailed forecast based on laboratory experiments, new data from other research groups and refined climate models. In the event of a nuclear war, the study predicted decreases in mean temperature by 20K and 75% less rainfall in mid-latitudes. It was also hypothesized that stabilizing the middle layers of the atmosphere would promote exchange between the hemispheres. As a result, the southern hemisphere would also be affected by the consequences of a war in the northern hemisphere.

See also

literature

- Paul R. Ehrlich , Carl Sagan : The nuclear night. The long-term climatic and biological effects of nuclear war. Kiepenheuer and Witsch, Cologne 1985, ISBN 3-462-01674-1 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Owen B. Toon, Charles G. Bardeen, Alan Robock, Lili Xia, Hans Kristensen: Rapidly expanding nuclear arsenals in Pakistan and India portend regional and global catastrophe . In: Science Advances . tape 5 , no. 10 , October 1, 2019, ISSN 2375-2548 , p. eaay5478 , doi : 10.1126 / sciadv.aay5478 ( sciencemag.org [accessed October 17, 2019]).

- ↑ Joachim Wille: Nuclear war would bring worldwide droughts. In: Klimareporter. October 17, 2019, accessed on October 17, 2019 (German).

- ^ Robock, A., L. Oman, and GL Stenchikov (2007), Nuclear winter revisited with a modern climate model and current nuclear arsenals: Still catastrophic consequences, J. Geophys. Res., 112, D13107, doi: 10.1029 / 2006JD008235

- ↑ Michael J. Mills, Owen B. Toon, Julia Lee-Taylor, Alan Robock: Multidecadal global cooling and unprecedented ozone loss following a regional nuclear conflict. Earth's Future, February 7, 2014, doi: 10.1002 / 2013EF000205

- ↑ Hampson J .: Photochemical was on the atmosphere . In: Nature . 250, No. 5463, 1974, pp. 189-91. doi : 10.1038 / 250189a0 .

- ^ Paul J. Crutzen ., Birks J .: The atmosphere after a nuclear war: Twilight at noon . In: Ambio . 11, 1982, pp. 114-25.

- ^ RP Turco, OB Toon, TP Ackerman, JB Pollack, and Carl Sagan : Nuclear Winter: Global Consequences of Multiple Nuclear Explosions . In: Science . 222, No. 4630, December 23, 1983, pp. 1283-92. doi : 10.1126 / science.222.4630.1283 . PMID 17773320 .

- ↑ Alexandrov, VV and GI Stenchikov (1983): On the modeling of the climatic consequences of the nuclear war The Proceeding of Appl. Mathematics, 21 p., The Computing Center of the AS USSR, Moscow.

- ↑ NUCLEAR WEAPONS: Nuclear Winter . In: Der Spiegel . No. 33 , 1984 ( online ).

- ^ Turco, RP, Toon, AB, Ackerman, TP, Pollack, JB, Sagan, C. (TTAPS) (January 1990). Climate and Smoke: An Appraisal of Nuclear Winter . Science 247: 167-8.