Operation Chromite

| date | September 15. bis 28. September 1950 |

|---|---|

| place | Incheon , South Korea |

| output | Victory of UN troops, recapture of Seoul |

| consequences | 1. Turn of the war |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

General Douglas MacArthur |

Kim Il-sung , NK Commander in Chief (in Pyongyang) |

| Troop strength | |

| 40,000 | 1000 on the beaches, 500 at the airport, 5000 in Seoul |

| losses | |

|

222 dead, |

3500+ dead / wounded / prisoners |

The Landing at Incheon (code name: Operation Chromite ) in September 1950 was an operation in the Korean War (1950-1953), in which the Allied forces under the command of General MacArthur succeeded in a bridgehead in the rear of the units advancing in the south of Korea to conquer the North Korean army and thus bring about a turnaround in the war.

prehistory

Associations of the North Korean Army had crossed the 38th parallel to the south on June 25, 1950 , thus triggering the Korean War and the USA's entry into the war on South Korea's side. They had already conquered Seoul on June 28 and by September had pushed the South Korean and US troops back into the area around Busan in the southeast of the peninsula.

General MacArthur, who was in Japan when the war broke out, had already inspected the combat area near Suwon near Seoul on June 29 and had begun the first plans for a later landing operation at Incheon . He had originally planned a landing for July ( Operation Blueheart ), but had been warned by his staff against hasty actions due to the complicated conditions for success and the rapidly deteriorating situation on land.

At the end of August 1950, the conditions for preparing a landing appeared to be significantly more favorable. The North Koreans had already pushed the UN troops and the remnants of the South Korean armed forces back onto the Busan bridgehead , but the front was gradually beginning to consolidate and the North Korean advance had lost its momentum due to the long supply lines and the heavy fighting. The best prospects for turning the overall situation around promised the landing at Incheon, the port city of Seoul, which had already been envisaged (here a large part of the supply lines by road or rail from North Korea to the south of the country), the other main supply line on the coastal road in the east the country could be controlled by the navy. With the capture of the port and the occupation of Seoul, the most important supply routes of the North Korean armed forces, 80–90% of which fought in South Korea, were cut in one fell swoop. The acquisition of another efficient port in the west would also improve the supply situation for the UN armed forces.

Preparations

However, landing at this point was also associated with great difficulties. The tide differences on the west coast of the Korean Peninsula are among the largest in the world, and the only access to the landing site that can be used by larger ships is through the so-called "Flying Fish Channel", a narrow strait with currents that vary widely from three to five knots. A few well-placed mines could render the canal unusable, making landing impossible. There were also great difficulties on land and on the coast; Incheon was already a large city with more than 200,000 inhabitants, which could lead to heavy house-to-house fighting. There were two fortified islands in front of the port: Wolmi-do and the smaller Sowolmi-do, connected to Wolmi-do by a dam; on the other landing beaches, dams, dykes and regular walls, which were supposed to hold back the tide, prevented a landing. In addition, despite the steadily arriving reinforcements, the Busan bridgehead was by no means stabilized to the extent that troops could be diverted for an amphibious landing at the other end of the peninsula without hesitation; other troops were not yet available. And time was of the essence, because there was only a narrow window of time for the landing operation, with favorable tides for the deep-going warships and dropships off Incheon . The closest time window opened in mid-September 1950, the next one would not come until a month later and was already too close to the Korean winter.

So there were just three weeks left to prepare for the venture, during which the landing had to be planned and carried out. Only thanks to the great mobility of the UN armed forces guaranteed by the command of the sea was such a high-risk undertaking, which was arranged in great haste, at all possible. During the Second World War , the navy and marine infantry had gained so much experience with the planning and execution of amphibious landing operations, especially in the Pacific theater, that many potential errors could be avoided during the operation, and there was still enough special material available. The centerpiece of the US X Corps landing forces was to be a brigade from the 1st Marine Division , which had participated in a large part of the fighting in South Korea in the past few weeks and played an important role as a mobile reserve in the defense of the Busan bridgehead. Pulling them out of the front line was a considerable risk, but one that had to be taken if the landing was to have any chance of success. The reconnaissance data necessary for planning the company was obtained from the aerial reconnaissance by landing reconnaissance specialists from the CIA and Navy, who scouted out the conditions at the intended landing sites and, in cooperation with the Korean population on site, also played a role in the landing itself (see below ).

The weather situation also caused difficulties, as a severe typhoon slowed the transport ships and damaged the port facilities in Kobe , Japan , which were important for loading and reloading the necessary equipment. A South Korean patrol boat also sank a North Korean mine-layer near Incheon, creating great uncertainty about possible mine closures near the landing site. Nevertheless, the ships and troops got to their starting positions in good time, and on September 13 the enterprise was able to start according to plan.

The landing

The actual landing was prepared by the exploration team that had landed days before on the island of Yonghung-do at the entrance to the port. On the American side, the X. Corps of the US Army took part under the command of Major General Edward M. Almond , consisting of the 1st Marine Infantry and 7th Infantry Divisions with a total strength of about 40,000 men, as well as 261 ships and numerous aircraft. The UN associations had absolute control of the sea and the air.

Two days before the planned landing began, a group of cruisers and destroyers (including British and Canadian units) appeared in front of Incheon and began the preparatory bombardment of the landing area. The reconnaissance team that had landed put the beacon on the Palmi-do peninsula back into operation, which provided the allied ships with valuable navigation aid. Meanwhile, minesweepers made sure that the Fliegender Fisch Canal was actually mine-free. The area was divided into three landing zones: Section “Red” ( Red Beach ) lay north of the city near the connection from Wolmi-do to the land, Section “Green” ( Green Beach ) denoted the west coast of Wolmi-do, while Section “Blue “( Blue Beach ) was in the southeast of the city. Because of their dominant position, the island of Wolmi-do and the neighboring Sowolmi-do had to be taken before the actual landing, which is why the first attack took place in the green section.

In the meantime the North Koreans had noticed the preparations and tried to retake Palmi-do. A North Korean landing craft was sunk by the reconnaissance troops, and the North Koreans retaliated against the civilian population who had supported the opposing agents. In conjunction with attacks by carrier aircraft, the North Korean positions on the red and green sections were badly hit by the artillery fire of the warships, and targeted attacks on identified ammunition depots also deprived the defenders of a substantial part of their resilience. The commander of the island fortress Wolmi-do was nevertheless confident that he would be able to refuse an attempted landing and reported this to his superiors. Despite the now obvious preparations, the North Korean leadership suspected, probably through misinformation launched by the enemy, that the main landing would take place further south in Gunsan , and therefore only sent weak forces to Incheon, who only appeared on the scene after the landing had already been carried out. As it was, however, just under 1,000 soldiers defended the beaches, with another 500 standing at Incheon Airport and 5000 in Seoul itself.

Green section

The first attack of the landing forces took place on Green Beach to conquer the two fortified islands off the harbor. Wolmi-do and the smaller Sowolmi-do were captured by the 5th Marine Regiment in the early morning hours of September 15 with relatively low losses. The defenders were held down on landing by ship artillery and air support, and tanks attacked the fortified positions with flamethrowers. Constant artillery fire and anti-tank mines laid on the only connecting bridge prevented an effective counterattack by the North Koreans until the main landing began in the late afternoon.

Section red

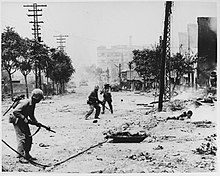

The landing in this section, as in the neighboring section Green, was tied to suitable tidal conditions, as the heavy LST landing ships needed enough water under the keel. This requirement did not come into effect again until late afternoon, which is why the attack here did not take place until the following flood. Special difficulties had to be overcome at Red Beach , as real sea walls had to be overcome here. Thanks to the good advance reconnaissance, the soldiers had suitable ladders available with which they could storm the walls and defeat the enemy positions. Then they cleared the head of the connecting bridge to Wolmi-do so that the tanks landed there could advance.

Section blue

On September 15, 1950 at 4:45 p.m. the hot phase of the actual landing operation on Blue Beach began . Cruisers and destroyers shot at the beaches - again supported by low-level attacks by the carrier aircraft. In some cases, however, the attacks were also aimed at the dikes in the landing zone, which obstructed the landing vehicles. The destruction of the dikes was incomplete, so that the heavy landing craft could not or only partially open their bow hatches. At 5:20 p.m., the first landing troops of the 1st Marine Regiment went ashore while the Navy was attempting a deception against the tidal port under construction. A heavy landing craft was sunk by artillery hits; the others made it safely to the beach. At this point, the Incheon defenders had capitulated, so the landing craft was hardly in danger of encountering resistance. Bulldozers landed in other sections later cleared the remains of the levees and the landing craft could be unloaded. The marines achieved their set goals without major difficulties and were able to secure the city of Incheon and the railway line to Seoul in particular . The normal port facilities at Incheon could be used again after only minor repairs, and just 24 hours after landing the situation was safe enough for the US X Corps to relocate its command post to the landing head.

Advance to Seoul

The day after the landing, Incheon was firmly in the hands of UN troops. The North Korean leadership tried to correct their misjudgment by bringing in a tank division that had been marched from Seoul towards Incheon and equipped with Soviet T-34s . Most of the tanks, however, fell victim to an American air strike, and the remainder were crushed by the landed M26 tanks. Documents from the pen of Kim Il-Sung captured on landing suggested that the North Koreans had been surprised by the UN intervention: "We had planned to end the war within a month, we could not destroy four American divisions [ ...] We were surprised when the UN troops and the American air force and navy approached. "

Two days after the landing, the advance on Seoul began, but it turned out to be considerably more difficult than the conquest of Incheon. The North Koreans did everything to stop the advance of the UN troops or at least to slow it down decisively. For this purpose, North Korean combat units were withdrawn from the south and Seoul was put on readiness for defense. More armored forces were deployed against Incheon and the port was attacked from the air. However, the attacks caused little damage. Meanwhile, the US armed forces landed more equipment and troops at full speed, pioneers repaired the railway line to Seoul, and with the capture of Gimpo airport reinforcements from the air were also able to reach the front. By September 22, 1950 - one week after the start of the attack - 53,882 soldiers, 6,629 vehicles and 25,512 tons of supplies had already been brought into the bridgehead.

With the help of air support from carrier aircraft, the 1st U.S. Marine Division and the 7th U.S. Infantry Division were able to occupy the north-south traffic arteries on the west coast and thus cut off supplies from the North Korean armies fighting in South Korea. On September 22nd, the Allied forces had reached the heavily fortified Seoul; fierce house-to-house fighting was required to drive the North Koreans out of the city. On September 25, the UN troops declared Seoul liberated. This explanation was a bit premature, however, because at that time there was still fierce fighting for the city. The background was that the UN troops had the opportunity to benefit from propaganda purposes from the success of having thrown back the North Korean aggressors in exactly three months, which seemed indispensable.

Although the landing itself is consistently regarded as a masterfully executed amphibious operation, the view was expressed that the advance inland was much too hesitant and that the surprise effect of the landing had largely fizzled out. After all, it took the Americans eleven days to capture Seoul, which is only about thirty kilometers from the landing zone, and thus interrupt the North Korean supply lines.

Collapse of the North Korean Army

At the same time as preparations for the landing, the North Korean armies had completed their own preparations for the major offensive on Busan, which was seeking a decision, and began the attack on September 1. The UN forces in the bridgehead were in great distress, but were able to bring the attacks to a halt and inflict heavy losses on the attackers using all reserves, utilizing their superior firepower and air support. Two weeks after the start of the offensive, the North Koreans were already severely weakened by the high number of failures and with the counter-offensive from the Busan bridgehead that began on September 16 at the same time as the attack against Incheon, the North Korean armed forces found themselves in a hopeless position. Attacked from the front and rear and cut off from their sources of supplies, the mass of the North Korean units, still numbering around 70,000 soldiers, who fought in South Korea, was overwhelmed or dispersed. Many of the scattered joined the partisans fighting in the impassable mountains. Although the fighting continued, the attacking UN forces found hardly any serious resistance and joined forces with the X Corps just ten days after the start of the attack south of Seoul. After this defeat, the North Korean leadership only had around 30,000 soldiers left, who were hopelessly inferior to the UN troops in Korea, which now numbered around 140,000.

consequences

With the elimination of a large part of the North Korean army, the North Koreans had to retreat beyond the 38th parallel. By the end of the year they were pushed back to the far north of the country, which triggered China's entry into the war in October 1950, which no western-oriented, united Korea was prepared to tolerate. The remaining North Korean troops served as cadres for the creation of new divisions to carry on the war.

literature

- Potter / Nimitz: Sea power. Pawlak 1982, ISBN 3-88199-082-8 .

Film adaptations

The first film adaptation of Inchon appeared in 1981 , and Operation Chromite followed in 2016 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Russel Stolfi: "A Critique of Pure Success: Incheon Revisited, Revised, and Contrasted." Journal of Military History 68 (2), 2004.