Paraskeva Pyatnitsa

Paraskeva Pyatnitsa (also Paraskeva from Ikonion , Paraskevi , Praskovia , Praskovie , Parascheva , Paraschiva ; * in Ikonion (today Konya in Turkey ) in Lycaonia ; † before 305 there) was a young Christian who martyred under the Roman emperor Diocletian and finally was beheaded in Iconium. She is venerated by the Russian Orthodox Church on October 28th. She is considered the patron saint of women's work and trade.

Surname

Saint Paraskeva Pyatnitsa has been particularly venerated among the Slavs since ancient times . The Greek name Paraskeva ( Greek. : Παρασκευή), which literally means "preparation" as a day of preparation for the weekend, the Sabbath means that "Friday" and on the day of the Passion of Christ suggesting that the Russian translation Pyatnitsa (was Russian ( пятница) - "Friday") added. According to the legends of the Orthodox Churches , Paraskeva Pyatnitsa was baptized on a Friday and was given her name in memory of both of the aforementioned events.

hagiography

Paraskeva Pyatnitsa was born during the reign of the Roman emperor Diocletian (284-305) in the city of Iconium in the Roman province of Lycaonia in the family of a wealthy "Synkletikos" ( senator ).

She was introduced to Christianity by her parents. When they died when she was very young, she inherited a considerable fortune. Instead of spending the fortune on luxury and pleasure, it helped the needy by providing food for the starving and homeless and clothing for those who could not afford it. She was so devoted to Christianity that she chose to remain a virgin and began to introduce Christianity to other people around her. At that time, however, Christianity was still a controversial feature in the Roman Empire and Christians were frequently persecuted.

When the Emperor Diocletian began persecuting Christians in 303 , he ordered Aetia, Governor of Lycaonia, to persecute and torture Christians in the cities under his control in order to exterminate the Christian faith.

Persecution under Diocletian

When Aetia arrived in Iconium, the city's elders bowed, worshiped the gods at his command, and handed Paraskeva over as an unrepentant Christian. Paraskeva was brought to court and asked to make a sacrifice to the gods, but she strictly refused. Because of this, she was subjected to torture. She was hung from a tree and beaten with nails. She was locked in the dungeon, half dead and with her flesh torn to the bone. An angel visited her that night and healed all of her wounds.

When she was brought to court again, the judge was amazed that she was in perfect health. Paraskeva then asked to be taken to the pagan temple. The judge, who said that she had changed her mind and wanted to convert to paganism , accompanied her to the temple himself. As soon as they entered, however, they called on the name of God and all the pagan gods collapsed. This annoyed the judge so much that he ordered Paraskeva to be cremated alive. Again Paraskeva was hung from a tree and burned with torches.

While engulfed in the flames, she continued to pray to the Christian God, surviving the ordeal unscathed. Shocked by what everyone saw, the pagans began with “ The Christian God is great! “To call. The judge furiously ordered the soldiers to behead the young woman.

One day after her death, the judge is said to have died unexpectedly, which Christians believed was an appropriate punishment from God. The body of the Paraskeva was dug in Iconium by the Christians and the relics of the Holy Great Martyr are said to have become a source of miracles .

Paraskeva Pyatnitsa churches are mainly in Russia and Poland .

wonder

Many healing miracles are ascribed to the Paraskeva. Before her death, she is said to have promised healing, wealth in houses, fields and cattle to those who built her a memorial. According to popular belief, the saint protects pious and happy homes. According to church belief, Saint Paraskeva Pyatnitsa is the protector of fields and cattle. Therefore, on their feast day, it is customary to bring fruits to the church for blessing, which will be kept until the following year. In addition, Paraskeva is revered for the protection of livestock diseases. In addition, she is also a healer for people suffering from severe physical and / or mental illness.

Representations

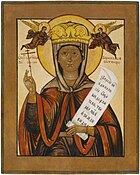

In Novgorod , Paraskeva Pyatnitsa, together with Saint Anastasia , was the patron saint of trade and fairs from the 12th century. Everywhere in northern Russia, where market days were held on Fridays, she was worshiped with icons, sculptures and in the churches sometimes built in her honor by merchants. But she is also represented with Saint Barbara and the Russian Saint Juliana , the patron saints of Russian women in the healing of mental illnesses; sometimes with male saints.

While most of the known representations are only formal figures, she is also depicted in the center of the picture with the events of her life, especially her martyrdom , that surround her .

In the 13th / 15th In the 19th century she was usually portrayed as a strict ascetic with a large stature and a shining crown on her head. She often wears the white maphorion (veil), symbol of chastity and the red cloak of the martyr . In her right hand she holds a Russian cross as a mark of martyrdom and in part in her right hand a scroll to show her faith.

Icon of the Greek saint Paraskeva, Archangel Cathedral in the Kremlin of Ryazan , central Russia

Icon of Saint Paraskeva, 19th century, Rybinsk Museum , Central Russia

Paraskeva in literature

The Byzantine writer and hagiographer Konstantin Akropolites wrote a hymn of praise to her and John of Euboea (1690–1730) wrote down her story of suffering.

See also

literature

- Linda J. Ivanits: Russian Folk Belief . Routledge, New York 1998, ISBN 0-87332-889-2 , pp. 33 (English, online preview in Google Book Search).

- Mike Dixon-Kennedy: Encyclopedia of Russian & Slavic Myth and Legend . 1998, ISBN 1-57607-063-8 , pp. 215 (English, online version in Google Book Search).

- Laura Egidia Laterza: I culti di Santa Parasceve (Veneranda) e della Madonna del Buon Consiglio . In: Albania: Conoscere, Comunicare, Condividere . Associazione Nazionale Comuni Italiani (ANCI) Apulia, 2004, p. 183 (Italian, online [PDF]).

- Nicholas Valentine Riasanovsky, Gleb Struve, Thomas Eekman: California Slavic Studies . tape 11 . University of California Press, Berkeley 1980, ISBN 0-520-03584-4 , pp. 38 ff . (English, online version in Google book search).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Anatoly Turilov: Турилов А. А. Межславянские культурные связи эпохи средневековья и источниковедение истории и культуры ( Inter-Slavic history and cultural relations of the Middle Ages and cultural relations) . Mosca 2012, ISBN 978-5-9551-0497-3 , pp. 111 (Russian, online version in the Google book search).

- ↑ a b c d Léonide Ouspensky, Vladimir Lossky: The Meaning of Icons . St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, Crestwood 1999, ISBN 0-913836-99-0 , pp. 136 (English, online preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b c d e Paraskeva, great martyr. In: Orthpedia.de. Retrieved September 16, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Paraskeva Pyatnitsa. In: Heiligenlexikon.de. Retrieved February 24, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Paul Bushkovitch: Urban ideology in medieval Novgorod : An iconographic approach . In: Cahiers du Monde Russe et Soviétiche Band = 16-1 . 1975, p. 21 (English).

- ↑ a b c d Saint Petka of the Saddlers Church. Retrieved February 24, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c Greatmartyr Paraskeva of Iconium. In: Oca.org. Retrieved February 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Remembrance day of the great martyr Paraskeva, called Friday. In: Calend.ru. Retrieved February 27, 2019 .

- ^ Carlo Pirovano: Il cielo in terra: icone russe dalla collezione . Comune di Bolzano, Bolzano 2001, p. 112 (Italian).

- ^ Helen C. Evans: Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261-1557) . Yale University Press, New Haven 2004, ISBN 1-58839-114-0 , pp. 89 (English, online preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ A b c Nicholas Valentine Riasanovsky, Gleb Struve, Thomas Eekman: California Slavic Studies . tape 11 . University of California Press, 1980, pp. 39 (English, online preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Thomas Froncek: The Horizon Book of the Arts of Russia . Simon & Schuster, New York 1970, ISBN 978-0-07-005260-4 , pp. 90 (English).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Paraskeva Pyatnitsa |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Paraskeva of Rome |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Preacher, martyr and saint |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 3rd century |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ikonion, today Konya in Turkey |

| DATE OF DEATH | before 305 |

| Place of death | Iconion |