Bad luck

Pecherei is the common expression in southern Lower Austria for the extraction of resin from black pines . Pecherei is used to obtain tree resin , also known as " pitch ", which is then processed into a number of chemical products. One who exercises the resin extraction are called Pecher . In 2011, bad luck in Lower Austria was included in the register of intangible cultural heritage in Austria , which was drawn up within the framework of the UNESCO Convention for the Conservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage .

The most important tree used for bad luck is the black pine ( Pinus nigra ), which is the most resinous tree of all European conifers and was already used by the Romans for resin extraction. At 90 to 120 years of age, a pine tree is at the best age for resin extraction. In Lower Austria, the Austrian black pine is the predominant tree, the resin of which is particularly high-quality and makes the Austrian pitch one of the best in the world.

history

In southern Lower Austria, especially in the industrial district and in the Vienna Woods , bad luck was probably practiced since the 17th century. A document from 1830 describes this as follows:

"The residents do agriculture and have their forests not far from the village in the mountains, from which they sell wood and pitch."

From the beginning of the 18th century, manors began to promote the mining of pitch, which led to the emergence of pitch huts for resin processing. During this time, bad luck and trading in the Harz became an important source of income for parts of the population.

In the first decades of the 19th century, resin extraction and pitch boiling experienced their first heyday, prices and yields also rose sharply due to the increasing demand.

Adalbert Stifter created a literary monument for this craft with his story Granit . Resin mining was an important source of income for the farming families in this region. From the 1960s, however, this industry slowly came to a standstill. The main reasons for this were cheap imports from the Eastern Bloc countries as well as from Turkey , Greece and Portugal . In addition, there were advances in technical chemistry, which made resin redundant as a raw material in many areas.

The Austrian social security law still knows the profession of the "independent bad luck", which is defined as follows:

"Self-employed Pecher, these are people who, without being employed on the basis of a service or apprenticeship, exercise a seasonally recurring gainful activity by extracting resin products in foreign forests, provided that they usually pursue this gainful activity without the help of non-family workers."

Raw materials and processing

The raw resin is light yellow. It is rich in organic hydrocarbons , poor in oxygen, and nitrogen free . Raw resin consists of a mixture of predominantly aromatic substances with acidic properties . The pitch owes its aromatic-spicy smell to the essential oils it contains .

The resin flow is different depending on the season and the weather, warmth and humidity have a beneficial effect. Three to four kilograms of pitch could be obtained per trunk and year. In order for a Pecher to live modestly with his family, he had to cut 2500 to 3000 trees. His working day usually began before sunrise with the march to work in the pine forest and often lasted ten to twelve hours.

The tree resin was melted from the "Harzbalsam" in "Pechhütten" in a distillation process, so-called "Boiling pitch", the impurities are skimmed off or sieved, while the turpentine oil and the water evaporate, which condensed and were collected in a vessel. The lighter turpentine floated on the top layer and was poured off. The "boiling pitch" freed from turpentine and water was after cooling a dark yellow, hard and brittle mass, the so-called "colophony". The turpentine oil and rosin obtained were mainly used in the paper , paint , soap , cable and shoe polish industries.

The annual work of the bad luck

The working year of the Pechers with different focus activities is structured according to the seasons. The most important work in winter was preparing the equipment and making the pitch notches with the notch planer .

The work was particularly complex in spring. Depending on the method used, the individual work steps differed:

Grandl or scrap method

At the beginning of the bad luck, the resin was collected at the lower end of the trunk in simple earth pits smeared with clay . Because of the resulting contamination of the resin, the Grandl or scrap method was developed. To do this, the Pecher worked a recess in the wood called “Grandl” or “Scrap” with the hoe close to the ground. Since the new resin container had to be smooth and clean, the Grandl was smoothed with a narrower hoe with a rounded edge, the moon or scrap hackl (3). With a pointed piece of wood, the Rowisch (1), the wood chips were removed from the inside. At the same time, the Rowisch served as a counting stick: after each new piece of scrap, the Pecher cut a notch in the Rowisch. So he always knew the number of trees that were finished.

With the dexel , which later became the guild symbol of bad luck, and the hoe (7), the badger then removed the bark from the tree trunk. In order to be able to direct the resin flow into the collecting container, pitch notches had to be created across the trunk.

About three times in two weeks, from spring to early autumn, sitting down followed as the oldest working method. The Pecher knocked down the bark piece by piece with the Plätzdexel (11) down to the trunk, so that the laugh grew bigger and the resin flow remained upright.

Depending on its size, a Grandl or scrap could take up between 0.25 and 0.35 kg of pitch. A tree worked in this way could provide bad luck for 12 to 18 years.

Zeschen and squares

In the inter-war period , the change from the Grandl to the beer mug method began, in which pitch mugs were used. To do this, new pitch trees, the "Heurigen", had to be raised off the ground with a hoe. In this process, the zeschen, the bark was removed from about a third of the trunk circumference first with the pickaxe (4) and then with the rintler (5) so that a V-shaped demarcation was created.

Then the Pecher had to use the Fürhackdexel (6) or the Anzeschaxe to create a groove on the right side of the tree trunk to accommodate the pitch notches, the let, chop and pull in the pitch notches. Just below the narrowest point, a beak was hacked out with the Fürhackdexel to receive the pitch oaf, a pitch nail (9) was hammered in one length below it and finally the pitch pot with the lid was put on. The tree was now ready for resin extraction and, as described above, had to be popped at regular intervals.

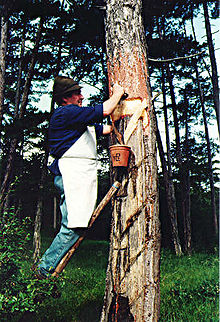

The trees that had been pitched for several years were processed in a similar way. When “chopping for”, the bad luck worker took his tools, the bad luck, the bad luck nail and the bad luck mug when climbing up the ladder. After removing the bark with the Rintler (5), chopping it up, i.e. removing the pebbled part at the edges of the pool, chopping it and inserting the pitch notches, instead of hitting the beak with the Fürhackdexel, the chopping iron (10) and hammer (11).

Cracks

As with all processing methods, the upper part of the tree bark had to be removed beforehand with the rintler (5) when grooving or scoring. Then the Pecher removed a layer of bark several millimeters thick with a scraper. A precise cut was important. With this planing process, no contiguous surfaces were created, but V-shaped grooves in the trunk. This saved the Pecher from inserting the pitch notches, as the resin could flow through the grooves into the pitch mug.

Although the scratching method saves work and time by eliminating the need for chopping, it was only used sporadically in southern Lower Austria, as the yield was up to 50% lower than with the two other resin extraction methods, squaring and planing. The main problem with the scribing process, however, was the clogging of the grooves with resin. That is why most of the Pecher returned to planing. The groove cut was mainly used when the Scots pine used resin .

Zeschen and planing

As it was very strenuous to sit down, the Pecher developed the new working method of planing. Not only was it less strenuous, it also took less time.

The working procedure for new pitch trees that had been worked on for several years remained the same as described above, only planing was used instead of digging. With the plane (12) the Pecher cut a wide, flat chip from the trunk with a single cut. When squatting, this could only be achieved with many blows from the Dexel. That way, it only took him about a sixth of the time it had taken to dexel.

The planing was not only practiced on newly created pitch trees, the so-called "Heurigen", but also on pines that had been worked for several years, as with seating a total of three times within two weeks, with the pitch usually once and in the first week the second week picked up twice. This was repeated about six to eight times until the mug was full and then started all over again.

The resin harvest

With the resin harvest, which takes place three to four times a year from spring to autumn, depending on the weather, the family and relatives usually help. The approximately 0.75 to 1 kg of the pitch oaf were emptied with the pitch spoon into the pitch pot, which held between 25 and 30 pitch oats, and this was again put into the pitch barrel. The so-called "Pechscherrn" was the last job of the Pechers in autumn. The solidified resin had to be removed from the pool with the Pechscherreisen (15). With the pitch tick, the Pecher scratched off the rigid resin on the edge of the notch and on the lass and took out the pitch notches. He emptied the resin caught in an apron, the Scherrpechpfiata, into the open-topped Scherrpechpfiata and trampled it with his feet. This Scherr pitch was of poorer quality than the Häferl pitch and therefore only achieved a lower price.

Other tools and facilities

The ladder was an indispensable tool for working on trees that had been pitched for several years. It was made from two thin, long pine trees that served as stiles and tough dogwood for the rungs. A professional pitcher climbed up to 22 rungs of the ladder, which corresponds to a height of 6 m, several hundred times a day, worked the trunk and then slid down with the leather slip patches attached to the thighs and knees .

According to old custom, a wooden Pecher hut was built in the middle of the forest. It resembled a wood chopper's hut and was mainly used as protection and refuge in bad weather. Inside there was usually a roughly timbered table and a bench. The Pecher ate here occasionally. Now and then there was also a stove. The Pecher almost always went home every day, only in exceptional cases did he spend the night in the hut. A ladder place was set up so that the ladders required to work on the trees of different heights did not always have to be taken home.

For the resin harvest, the filling, initially (trickle) pitch barrels made of hardwood, later iron and finally plastic barrels were half buried in the forest floor and remained in the forest until they were transported to the pitch processing plant. A full wooden barrel weighed between 130 and 160 kg, an iron barrel between 180 and 200 kg.

To keep the snack that he brought along cool, especially in summer , the Pecher built a water pit in a shady place. To do this, he lifted the soil, put up side walls with stones, also put a lid on from a stone and finally sprinkled the small pit with brushwood.

Effects on the tree

In contrast to the pitching practiced in the beginning by burning off the bark over the entire trunk circumference of the pine tree, in which the tree died, the more modern form, in which the bark is only removed from around a third of the trunk circumference, does not affect the viability of the tree. Although the trunk in the area of the exposed wood is more susceptible to the effects of the weather and pests, the tree wound is also preserved and protected by the escaping resin. It is therefore possible to pitch a pine a second time - on the opposite side. The supply of water and nutrients to the crown is then ensured by two narrow, opposite strips of bark, the "life", so that the tree can continue to grow in this case too. Such trees were called "life guides".

The wood from pitched trees, however, is of lower quality than the less pitched and is therefore only used as firewood.

Web links

- Harzung on forstwirtin.bplaced.net, accessed on January 4, 2017.

- Pecherlehrpfad Hölles ( Austria )

- Pecher in Voeslau ( Memento from June 24, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- Ursula Schnabl; About luck with bad luck (the traditional use and extraction of vegetable raw materials and work materials using the example of Austrian resin extraction). Diploma thesis at the Institute of Botany at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, 2001 (PDF file; 1.46 MB).

literature

- Herbert Kohlross (Ed.): The black pine in Austria . Their extraordinary importance for nature, economy and culture. Self-published, Gutenstein 2006. ISBN 3-200-00720-6

- Erwin Greiner: Pecher, Pech and Piesting. A local historical documentation about the Schwarzföhre, the Pech, the Pecher and the Harzwerk as well as about the early history of Markt Piesting and the surrounding area. Tourist office, Markt Piesting. Niederösterreichische Verlags Gesmbh, Wiener Neustadt 1988.

- Heinz Cibulka, Wieland Schmied: In the pitch forest . Edition Hentrich, Vienna-Berlin 1986. ISBN 3-926175-13-3

- Helene Grünn: The bad luck . Folklore from the forest. Manutiuspresse, Vienna-Munich 1960.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bad luck in Lower Austria ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. National Agency for the Intangible Cultural Heritage, accessed April 3, 2011.

- ↑ Friedrich Schweickhardt: Representation of the Archduchy of Austria under the Ens, through a comprehensive description of all castles, palaces, lordships, cities, markets, villages, Rotten, C., C., topographical-statistical-genealogical-historical edited, and according to the existing ones lined up in four quarters . 3rd edition, Volume 2, Part 2, Vienna 1834, p. 271.

- ↑ Section 1, Paragraph 1, Letter f of the Unemployment Insurance Act as amended on January 1, 2004.

- ^ Ferdinand Schubert: Handbuch der Forstchemie. Brockhaus, Leipzig 1848, p. 657 f.